neurological disorders

Study Suggests During Sleep, Neural Process Helps Clear the Brain of Damaging Waste

Posted on by Dr. Monica M. Bertagnolli

We’ve long known that sleep is a restorative process necessary for good health. Research has also shown that the accumulation of waste products in the brain is a leading cause of numerous neurological disorders, including Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases. What hasn’t been clear is how the healthy brain “self-cleans,” or flushes out that detrimental waste.

But a new study by a research team supported in part by NIH suggests that a neural process that happens while we sleep helps cleanse the brain, leading us to wake up feeling rested and restored. Better understanding this process could one day lead to methods that help people function well on less sleep. It could also help researchers find potential ways to delay or prevent neurological diseases related to accumulated waste products in the brain.

The findings, reported in Nature, show that, during sleep, neural networks in the brain act like an array of miniature pumps, producing large and rhythmic waves through synchronous bursts of activity that propel fluids through brain tissue. Much like the process of washing dishes, where you use a rhythmic motion of varying speeds and intensity to clear off debris, this process that takes place during sleep clears accumulated metabolic waste products out.

The research team, led by Jonathan Kipnis and Li-Feng Jiang-Xie at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, wanted to better understand how the brain manages its waste. This is not an easy task, given that the human brain’s billions of neurons inevitably produce plenty of junk during cognitive processes that allow us to think, feel, move, and solve problems. Those waste products also build in a complex environment, including a packed maze of interconnected neurons, blood vessels, and interstitial spaces, surrounded by a protective blood-brain barrier that limits movement of substances in or out.

So, how does the brain move fluid through those tight spaces with the force required to get waste out? Earlier research suggested that neural activity during sleep might play an important role in those waste-clearing dynamics. But previous studies hadn’t pinned down the way this works.

To learn more in the new study, the researchers recorded brain activity in mice. They also used an ultrathin silicon probe to measure fluid dynamics in the brain’s interstitial spaces. In awake mice, they saw irregular neural activity and only minor fluctuations in the interstitial spaces. But when the animals were resting under anesthesia, the researchers saw a big change. Brain recordings showed strongly enhanced neural activity, with two distinct but tightly coupled rhythms. The research team realized that the structured wave patterns could generate strong energy that could move small molecules and peptides, or waste products, through the tight spaces within brain tissue.

To make sure that the fluid dynamics were really driven by neurons, the researchers used tools that allowed them to turn neural activity off in some areas. Those experiments showed that, when neurons stopped firing, the waves also stopped. They went on to show similar dynamics during natural sleep in the animals and confirmed that disrupting these neuron-driven fluid dynamics impaired the brain’s ability to clear out waste.

These findings highlight the importance of this cleansing process during sleep for brain health. The researchers now want to better understand how specific patterns and variations in those brain waves lead to changes in fluid movement and waste clearance. This could help researchers eventually find ways to speed up the removal of damaging waste, potentially preventing or delaying certain neurological diseases and allowing people to need less sleep.

Reference:

[1] Jiang-Xie LF, et al. Neuronal dynamics direct cerebrospinal fluid perfusion and brain clearance. Nature. DOI: 10.1038/s41586-024-07108-6 (2024).

NIH Support: National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health

Brain Atlas Paves the Way for New Understanding of How the Brain Functions

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

When NIH launched The BRAIN Initiative® a decade ago, one of many ambitious goals was to develop innovative technologies for profiling single cells to create an open-access reference atlas cataloguing the human brain’s many parts. The ultimate goal wasn’t to produce a single, static reference map, but rather to capture a dynamic view of how the brain’s many cells of varied types are wired to work together in the healthy brain and how this picture may shift in those with neurological and mental health disorders.

So I’m now thrilled to report the publication of an impressive collection of work from hundreds of scientists in the BRAIN Initiative Cell Census Network (BICCN), detailed in more than 20 papers in Science, Science Advances, and Science Translational Medicine.1 Among many revelations, this unprecedented, international effort has characterized more than 3,000 human brain cell types. To put this into some perspective, consider that the human lung contains 61 cell types.2 The work has also begun to uncover normal variation in the brains of individual people, some of the features that distinguish various disease states, and distinctions among key parts of the human brain and those of our closely related primate cousins.

Of course, it’s not possible to do justice to this remarkable body of work or its many implications in the space of a single blog post. But to give you an idea of what’s been accomplished, some of these studies detail the primary effort to produce a comprehensive brain atlas, including defining the brain’s many cell types along with their underlying gene activity and the chemical modifications that turn gene activity up or down.3,4,5

Other studies in this collection take a deep dive into more specific brain areas. For instance, to capture normal variations among people, a team including Nelson Johansen, University of California, Davis, profiled cells in the neocortex—the outermost portion of the brain that’s responsible for many complex human behaviors.6 Overall, the work revealed a highly consistent cellular makeup from one person to the next. But it also highlighted considerable variation in gene activity, some of which could be explained by differences in age, sex and health. However, much of the observed variation remains unexplained, opening the door to more investigations to understand the meaning behind such brain differences and their role in making each of us who we are.

Yang Li, now at Washington University in St. Louis, and his colleagues analyzed 1.1 million cells from 42 distinct brain areas in samples from three adults.4 They explored various cell types with potentially important roles in neuropsychiatric disorders and were able to pinpoint specific cell types, genes and genetic switches that may contribute to the development of certain traits and disorders, including bipolar disorder, depression and schizophrenia.

Yet another report by Nikolas Jorstad, Allen Institute, Seattle, and colleagues delves into essential questions about what makes us human as compared to other primates like chimpanzees.7 Their comparisons of gene activity at the single-cell level in a specific area of the brain show that humans and other primates have largely the same brain cell types, but genes are activated differently in specific cell types in humans as compared to other primates. Those differentially expressed genes in humans often were found in portions of the genome that show evidence of rapid change over evolutionary time, suggesting that they play important roles in human brain function in ways that have yet to be fully explained.

All the data represented in this work has been made publicly accessible online for further study. Meanwhile, the effort to build a more finely detailed picture of even more brain cell types and, with it, a more complete understanding of human brain circuitry and how it can go awry continues in the BRAIN Initiative Cell Atlas Network (BICAN). As impressive as this latest installment is—in our quest to understand the human brain, brain disorders, and their treatment—we have much to look forward to in the years ahead.

References:

A list of all the papers part of the brain atlas research is available here: https://www.science.org/collections/brain-cell-census.

[1] M Maroso. A quest into the human brain. Science DOI: 10.1126/science.adl0913 (2023).

[2] L Sikkema, et al. An integrated cell atlas of the lung in health and disease. Nature Medicine DOI: 10.1038/s41591-023-02327-2 (2023).

[3] K Siletti, et al. Transcriptomic diversity of cell types across the adult human brain. Science DOI: 10.1126/science.add7046 (2023).

[4] Y Li, et al. A comparative atlas of single-cell chromatin accessibility in the human brain. Science DOI: 10.1126/science.adf7044 (2023).

[5] W Tian, et al. Single-cell DNA methylation and 3D genome architecture in the human brain. Science DOI: 10.1126/science.adf5357 (2023).

[6] N Johansen, et al. Interindividual variation in human cortical cell type abundance and expression. Science DOI: 10.1126/science.adf2359 (2023).

[7] NL Jorstad, et al. Comparative transcriptomics reveals human-specific cortical features. Science DOI: 10.1126/science.ade9516 (2023).

NIH Support: Projects funded through the NIH BRAIN Initiative Cell Consensus Network

Robotic Exoskeleton Could Be Right Step Forward for Kids with Cerebral Palsy

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

More than 17 million people around the world are living with cerebral palsy, a movement disorder that occurs when motor areas of a child’s brain do not develop correctly or are damaged early in life. Many of those affected were born extremely prematurely and suffered brain hemorrhages shortly after birth. One of the condition’s most common symptoms is crouch gait, which is an excessive bending of the knees that can make it difficult or even impossible to walk. Now, a new robotic device developed by an NIH research team has the potential to help kids with cerebral palsy walk better.

What’s really cool about the robotic brace, or exoskeleton, which you see demonstrated above, is that it’s equipped with computerized sensors and motors that can detect exactly where a child is in the walking cycle—delivering bursts of support to the knees at just the right time. In fact, in a small study of seven young people with crouch gait, the device enabled six to stand and walk taller in their very first practice session!

Huntington’s Disease: Gene Editing Shows Promise in Mouse Studies

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

My father was a folk song collector, and I grew up listening to the music of Woody Guthrie. On July 14th, folk music enthusiasts will be celebrating the 105th anniversary of Guthrie’s birth in his hometown of Okemah, OK. Besides being renowned for writing “This Land is Your Land” and other folk classics, Guthrie has another more tragic claim to fame: he provided the world with a glimpse at the devastation caused by a rare, inherited neurological disorder called Huntington’s disease.

My father was a folk song collector, and I grew up listening to the music of Woody Guthrie. On July 14th, folk music enthusiasts will be celebrating the 105th anniversary of Guthrie’s birth in his hometown of Okemah, OK. Besides being renowned for writing “This Land is Your Land” and other folk classics, Guthrie has another more tragic claim to fame: he provided the world with a glimpse at the devastation caused by a rare, inherited neurological disorder called Huntington’s disease.

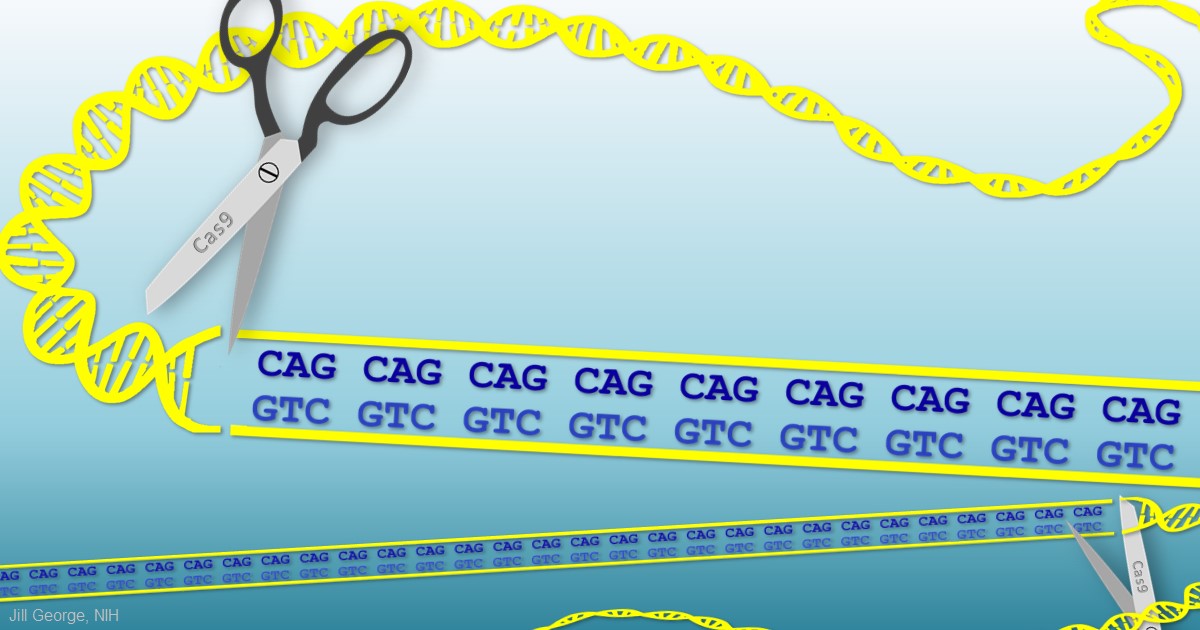

When Guthrie died from complications of Huntington’s a half-century ago, the disease was untreatable. Sadly, it still is. But years of basic science advances, combined with the promise of innovative gene editing systems such as CRISPR/Cas9, are providing renewed hope that we will someday be able to treat or even cure Huntington’s disease, along with many other inherited disorders.

Creative Minds: Modeling Neurobiological Disorders in Stem Cells

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Most neurological and psychiatric disorders are profoundly complex, involving a variety of environmental and genetic factors. Researchers around the world have worked with patients and their families to identify hundreds of possible genetic leads to learn what goes wrong in autism spectrum disorder, schizophrenia, and other conditions. The great challenge now is to begin examining this growing cache of information more systematically to understand the mechanism by which these gene variants contribute to disease risk—potentially providing important information that will someday lead to methods for diagnosis and treatment.

Meeting this profoundly difficult challenge will require a special set of laboratory tools. That’s where Feng Zhang comes into the picture. Zhang, a bioengineer at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, MA, has made significant contributions to a number of groundbreaking research technologies over the past decade, including optogenetics (using light to control brain cells), and CRISPR/Cas9, which researchers now routinely use to edit genomes in the lab [1,2].

Zhang has received a 2015 NIH Director’s Transformative Research Award to develop new tools to study multiple gene variants that might be involved in a neurological or psychiatric disorder. Zhang draws his inspiration from nature, and the microscopic molecules that various organisms have developed through the millennia to survive. CRISPR/Cas9, for instance, is a naturally occurring bacterial defense system that Zhang and others have adapted into a gene-editing tool.

Brain Imaging: Advance Aims for Epilepsy’s Hidden Hot Spots

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

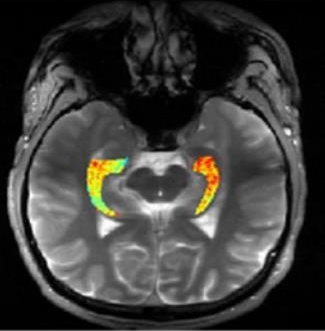

Credit: Reddy Lab, University of Pennsylvania

For many of the 65 million people around the world with epilepsy, modern medications are able to keep the seizures under control. When medications fail, as they do in about one-third of people with epilepsy, surgery to remove affected brain tissue without compromising function is a drastic step, but offers a potential cure. Unfortunately, not all drug-resistant patients are good candidates for such surgery for a simple reason: their brains appear normal on traditional MRI scans, making it impossible to locate precisely the source(s) of the seizures.

Now, in a small study published in Science Translational Medicine [1], NIH-funded researchers report progress towards helping such people. Using a new MRI method, called GluCEST, that detects concentrations of the nerve-signaling chemical glutamate in brain tissue [2], researchers successfully pinpointed seizure-causing areas of the brain in four of four volunteers with drug-resistant epilepsy and normal traditional MRI scans. While the findings are preliminary and must be confirmed by larger studies, researchers are hopeful that GluCEST, which takes about 30 minutes, may open the door to new ways of treating this type of epilepsy.