organoid

Mini-Lungs in a Lab Dish Mimic Early COVID-19 Infection

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Researchers have become skilled at growing an array of miniature human organs in the lab. Such lab-grown “organoids” have been put to work to better understand diabetes, fatty liver disease, color vision, and much more. Now, NIH-funded researchers have applied this remarkable lab tool to produce mini-lungs to study SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19.

The intriguing bubble-like structures (red/clear) in the mini-lung pictured above represent developing alveoli, the tiny air sacs in our lungs, where COVID-19 infections often begin. In this organoid, the air sacs consist of many thousands of cells, all of which arose from a single adult stem cell isolated from tissues found deep within healthy human lungs. When carefully nurtured in lab dishes, those so-called alveolar epithelial type-2 cells (AT2s) begin to multiply. As they grow, they spontaneously assemble into structures that closely resemble alveoli.

A team led by Purushothama Rao Tata, Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, NC, developed these mini-lungs in a quest to understand how adult stem cells help to regenerate damaged tissue in the deepest recesses of the lungs, where SARS-CoV-2 attacks. In earlier studies, the researchers had shown it was possible for these cells to produce miniature alveoli. But there was a problem: the “soup” they used to nurture the growing cells included ingredients that weren’t well defined, making it hard to characterize the experiments fully.

In the study, now reported in Cell Stem Cell, the researchers found a way to simplify and define that brew. For the first time, they could produce mini-lungs consisting only of human lung cells. By growing them in large numbers in the lab, they can now learn more about SARS-CoV-2 infection and look for new ways to prevent or treat it.

Tata and his collaborators at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, have already confirmed that SARS-CoV-2 infects the mini-lungs via the critical ACE2 receptor, just as the virus is known to do in the lungs of an infected person.

Interestingly, the cells also produce cytokines, inflammatory molecules that have been tied to tissue damage. The findings suggest the cytokine signals may come from the lungs themselves, even before immune cells arrive on the scene.

The heavily infected lung cells eventually self-destruct and die. In an unexpected turn of events, they even induce cell death in some neighboring healthy cells that are not infected. The relevance of the studies to the clinic was boosted by the finding that the gene activity patterns in the mini-lungs are a close match to those found in samples taken from six patients with severe COVID-19.

Now that he’s got the recipe down, Tata is busy making organoids and helping to model COVID-19 infections, with the hope of identifying and testing promising new treatments. It’s clear these mini-lungs are breathing some added life into the basic study of COVID-19.

Reference:

[1] Human lung stem cell-based alveolospheres provide insights into SARS-CoV-2-mediated interferon responses and pneumocyte dysfunction. Katsura H, Sontake V, Tata A, Kobayashi Y, Edwards CE, Heaton BE, Konkimalla A, Asakura T, Mikami Y, Fritch EJ, Lee PJ, Heaton NS, Boucher RC, Randell SH, Baric RS, Tata PR. Cell Stem Cell. 2020 Oct 21:S1934-5909(20)30499-9.

Links:

Coronavirus (COVID-19) (NIH)

Tata Lab (Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, NC)

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institute of General Medical Sciences; National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

Modeling Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy in a Dish

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: Zhen Ma, University of California, Berkeley

Researchers have learned in recent years how to grow miniature human hearts in a dish. These “organoids” beat like the real thing and have allowed researchers to model many key aspects of how the heart works. What’s been really tough to model in a dish is how stresses on hearts that are genetically abnormal, such as in inherited familial cardiomyopathies, put people at greater risk for cardiac problems.

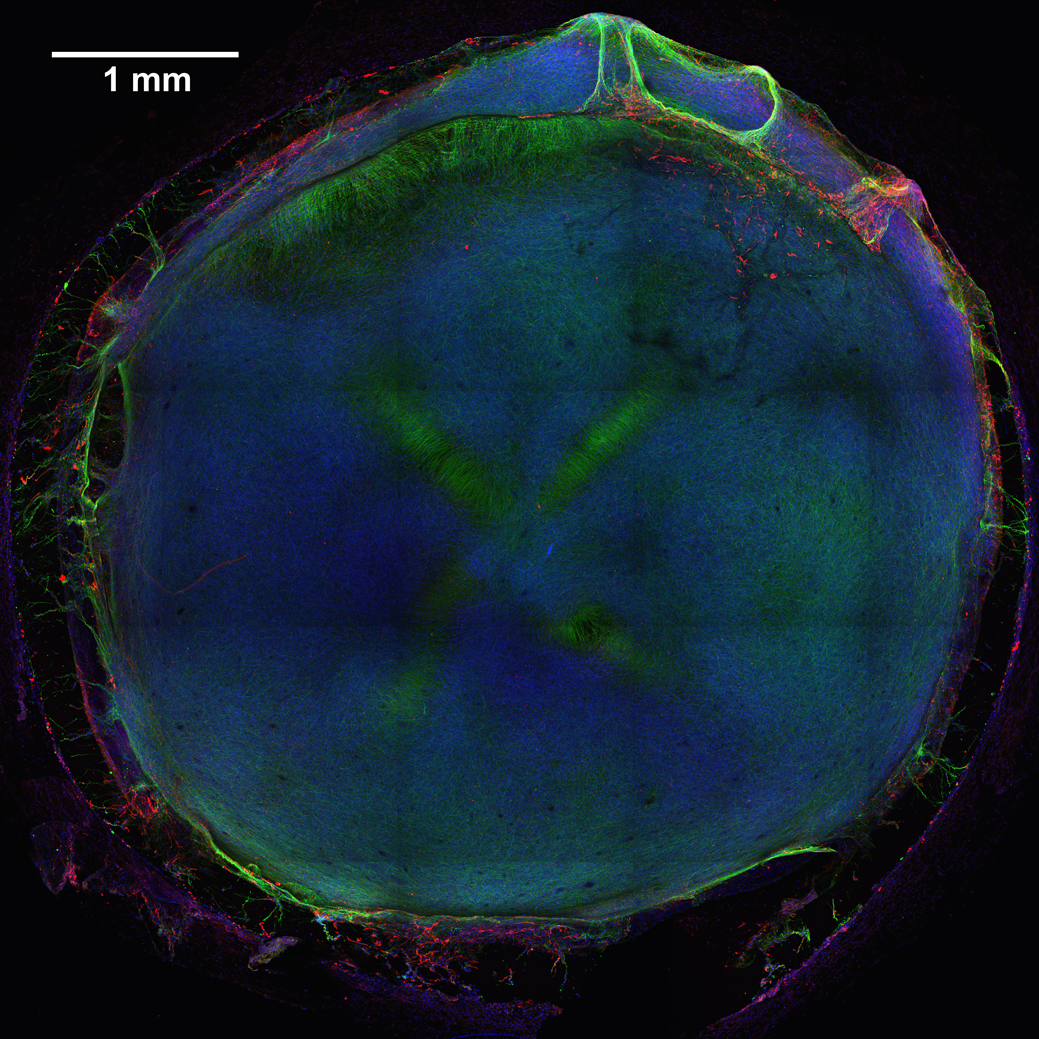

Enter the lab-grown human cardiac tissue pictured above. This healthy tissue comprised of the heart’s muscle cells, or cardiomyocytes (green, nuclei in red), was derived from induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells. These cells are derived from adult skin or blood cells that are genetically reprogrammed to have the potential to develop into many different types of cells, including cardiomyocytes.

Creative Minds: Modeling Neurobiological Disorders in Stem Cells

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Most neurological and psychiatric disorders are profoundly complex, involving a variety of environmental and genetic factors. Researchers around the world have worked with patients and their families to identify hundreds of possible genetic leads to learn what goes wrong in autism spectrum disorder, schizophrenia, and other conditions. The great challenge now is to begin examining this growing cache of information more systematically to understand the mechanism by which these gene variants contribute to disease risk—potentially providing important information that will someday lead to methods for diagnosis and treatment.

Meeting this profoundly difficult challenge will require a special set of laboratory tools. That’s where Feng Zhang comes into the picture. Zhang, a bioengineer at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, MA, has made significant contributions to a number of groundbreaking research technologies over the past decade, including optogenetics (using light to control brain cells), and CRISPR/Cas9, which researchers now routinely use to edit genomes in the lab [1,2].

Zhang has received a 2015 NIH Director’s Transformative Research Award to develop new tools to study multiple gene variants that might be involved in a neurological or psychiatric disorder. Zhang draws his inspiration from nature, and the microscopic molecules that various organisms have developed through the millennia to survive. CRISPR/Cas9, for instance, is a naturally occurring bacterial defense system that Zhang and others have adapted into a gene-editing tool.

If I Only Had a Brain? Tissue Chips Predict Neurotoxicity

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: 3D neural tissue chips contain neurons (green), glial cells (red), and nuclei (blue). To take this confocal micrograph, developing neural tissue was removed from a chip and placed on a glass-bottom Petri dish.

Credit: Michael Schwartz, Dept. of Bioengineering, University of Wisconsin-Madison

A lot of time, money, and effort are devoted to developing new drugs. Yet only one of every 10 drug candidates entering human clinical trials successfully goes on to receive approval from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) [1]. Many would-be drugs fall by the wayside because they prove toxic to the brain, liver, kidneys, or other organs—toxicity that, unfortunately, isn’t always detected in preclinical studies using mice, rats, or other animal models. That explains why scientists are working so hard to devise technologies that can do a better job of predicting early on which chemical compounds will be safe in humans.

As an important step in this direction, NIH-funded researchers at the Morgridge Institute for Research and University of Wisconsin-Madison have produced neural tissue chips with many features of a developing human brain. Each cultured 3D “organoid”—which sits comfortably in the bottom of a pea-sized well on a standard laboratory plate—comes complete with its very own neurons, support cells, blood vessels, and immune cells! As described in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences [2], this new tool is poised to predict earlier, faster, and less expensively which new or untested compounds—be they drug candidates or even ingredients in cosmetics and pesticides—might harm the brain, particularly at the earliest stages of development.