microglia

Study Suggests Treatments that Unleash Immune Cells in the Brain Could Help Combat Alzheimer’s

Posted on by Dr. Monica M. Bertagnolli

In Alzheimer’s disease, a buildup of sticky amyloid proteins in the brain clump together to form plaques, causing damage that gradually leads to worsening dementia symptoms. A promising way to change the course of this disease is with treatments that clear away damaging amyloid plaques or stop them from forming in the first place. In fact, the Food and Drug Administration recently approved the first drug for early Alzheimer’s that moderately slows cognitive decline by reducing amyloid plaques.1 Still, more progress is needed to combat this devastating disease that as many as 6.7 million Americans were living with in 2023.

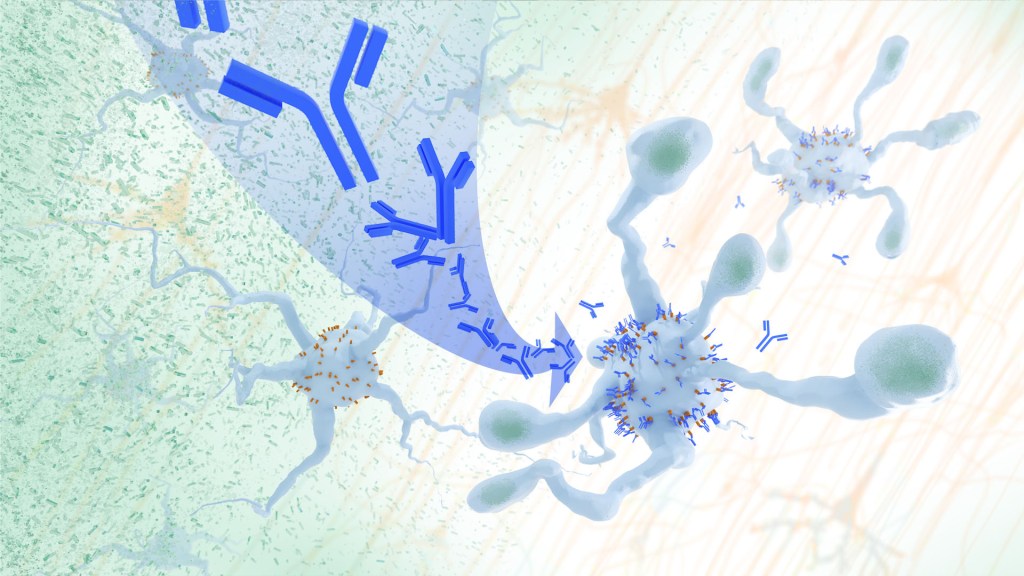

Recent findings from a study in mice, supported in part by NIH and reported in Science Translational Medicine, offer another potential way to clear amyloid plaques in the brain. The key component of this strategy is using the brain’s built-in cleanup crew for amyloid plaques and other waste products: immune cells known as microglia that naturally help to limit the progression of Alzheimer’s. The findings suggest it may be possible to develop immunotherapies—treatments that use the body’s immune system to fight disease—to activate microglia in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s and clear amyloid plaques more effectively.2

In their report, the research team—including Marco Colonna, Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, and Jinchao Hou, now at Children’s Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine in Zhejiang Province, China—wrote that microglia in the brain surround plaques to create a barrier that controls their spread. Microglia can also destroy amyloid plaques directly. But how microglia work in the brain depends on a fine-tuned balance of signals that activate or inhibit them. In people with Alzheimer’s, microglia don’t do their job well enough.

The researchers suspected this might have something to do with a protein called apolipoprotein E (APOE). This protein normally helps carry cholesterol and other fats in the bloodstream. But the gene encoding the protein is known for its role in influencing a person’s risk for developing Alzheimer’s, and in the Alzheimer’s brain, the protein is a key component of amyloid plaques. The protein can also inactivate microglia by binding to a receptor called LILRB4 found on the immune cells’ surfaces.

Earlier studies in mouse models of Alzheimer’s showed that the LILRB4 receptor is expressed at high levels in microglia when amyloid plaques build up. This suggested that treatments targeting this receptor on microglia might hold promise for treating Alzheimer’s. In the new study, the research team looked for evidence that an increase in LILRB4 receptors on microglia plays an important role in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s.

To do this, the researchers first studied brain tissue samples from people who died with this disease and discovered unusually high amounts of the LILRB4 receptor on the surfaces of microglia, similar to what had been seen in the mouse models. This could help explain why microglia struggle to control amyloid plaques in the Alzheimer’s brain.

Next, the researchers conducted studies of mouse brains with accumulating amyloid plaques that express the LILRB4 receptor to see if an antibody targeting the receptor could lower amyloid levels by boosting activity of immune microglia. Their findings suggest that the antibody treatment blocked the interaction between APOE proteins and LILRB4 receptors and enabled microglia to clear amyloid plaques. Intriguingly, the team’s additional studies found that this clearing process also changed the animals’ behavior, making them less likely to take risks. That’s important because people with Alzheimer’s may engage in risky behaviors as they lack memories of earlier experiences that they could use to make decisions.

There’s plenty more to learn. For instance, the researchers don’t know yet whether this approach will affect the tau protein, which forms damaging tangles inside neurons in the Alzheimer’s brain. They also want to investigate whether this strategy of clearing amyloid plaques might come with other health risks.

But overall, these findings add to evidence that immunotherapies of this kind could be a promising way to treat Alzheimer’s. This strategy may also have implications for treating other neurodegenerative conditions characterized by toxic debris in the brain, such as Parkinson’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and Huntington’s disease. The hope is that this kind of research will ultimately lead to more effective treatments for Alzheimer’s and other conditions affecting the brain.

References:

[1] FDA Converts Novel Alzheimer’s Disease Treatment to Traditional Approval. U.S. Food and Drug Administration (2023).

[2] Hou J, et al. Antibody-mediated targeting of human microglial leukocyte Ig-like receptor B4 attenuates amyloid pathology in a mouse model. Science Translational Medicine. DOI: 10.1126/scitranslmed.adj9052 (2024).

NIH Support: National Institute of General Medical Sciences, National Institute on Aging

Taking a Deep Dive into the Alzheimer’s Brain in Search of Understanding and New Targets

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

People living with Alzheimer’s disease experience a gradual erosion of memory and thinking skills until they can no longer carry out daily activities. Hallmarks of the disease include the buildup of plaques that collect between neurons, accumulations of tau protein inside neurons and weakening of neural connections. However, there’s still much to learn about what precisely happens in the Alzheimer’s brain and how the disorder’s devastating march might be slowed or even stopped. Alzheimer’s affects more than six million people in the United States and is the seventh leading cause of death among adults in the U.S., according to the National Institute on Aging.

NIH-supported researchers recently published a trove of data in the journal Cell detailing the molecular drivers of Alzheimer’s disease and which cell types in the brain are most likely to be affected.1,2,3,4 The scientists, led by Li-Huei Tsai and Manolis Kellis, both at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, characterized gene activity at the single-cell level in more than two million cells from postmortem brain tissue. They also assessed DNA damage and surveyed epigenetic changes in cells, which refers to chemical modifications to DNA that alter gene expression in the cell. The findings could help researchers pinpoint new targets for Alzheimer’s disease treatments.

In the first of four studies, the researchers examined 54 brain cell types in 427 brain samples from a cohort of people with varying levels of cognitive impairment that has been followed since 1994.1 The MIT team generated an atlas of gene activity patterns within the brain’s prefrontal cortex, an important area for memory retrieval.

Their analyses in brain samples taken from people with Alzheimer’s dementia showed altered activity in genes involved in various functions. Additional findings showed that people with normal cognitive abilities with evidence of plaques in their brains had more neurons that inhibit or dampen activity in the prefrontal cortex compared to those with Alzheimer’s dementia. The finding suggests that the workings of inhibitory neurons may play an unexpectedly important role in maintaining cognitive resilience despite age-related changes, including the buildup of plaques. It’s one among many discoveries that now warrant further study.

In another report, the researchers compared brain tissues from 48 people without Alzheimer’s to 44 people with early- or late-stage Alzheimer’s.2 They developed a map of the various elements that regulate function within cells in the prefrontal cortex. By cross-referencing epigenomic and gene activity data, the researchers showed changes in many genes with known links to Alzheimer’s disease development and risk.

Their single-cell analysis also showed that these changes most often occur in microglia, which are immune cells that remove cellular waste products from the brain. At the same time, every cell type they studied showed a breakdown over time in the cells’ normal epigenomic patterning, a process that may cause a cell to behave differently as it loses essential aspects of its original identity and function.

In a third report, the researchers looked even deeper into gene activity within the brain’s waste-clearing microglia.3 Based on the activity of hundreds of genes, they were able to define a dozen distinct microglia “states.” They also showed that more microglia enter an inflammatory state in the Alzheimer’s brain compared to a healthy human brain. Fewer microglia in the Alzheimer’s brain were in a healthy, balanced state as well. The findings suggest that treatments that target microglia to reduce inflammation and promote balance may hold promise for treating Alzheimer’s disease.

The fourth and final report zeroed in on DNA damage, inspired in part by earlier findings suggesting greater damage within neurons even before Alzheimer’s symptoms appear.4 In fact, breaks in DNA occur as part of the normal process of forming new memories. But those breaks in the healthy brain are quickly repaired as the brain makes new connections.

The researchers studied postmortem brain tissue samples and found that, over time in the Alzheimer’s brain, the damage exceeds the brain’s ability to repair it. As a result, attempts to put the DNA back together leads to a patchwork of mistakes, including rearrangements in the DNA and fusions as separate genes are merged. Such changes appear to arise especially in genes that control neural connections, which may contribute to the signs and symptoms of Alzheimer’s.

The researchers say they now plan to apply artificial intelligence and other analytic tools to learn even more about Alzheimer’s disease from this trove of data. To speed progress even more, they’ve made all the data freely available online to the research community, where it promises to yield many more fundamentally important discoveries about the precise underpinnings of Alzheimer’s disease in the brain and new ways to intervene in Alzheimer’s dementia.

References:

[1] Mathys H, et al. Single-cell atlas reveals correlates of high cognitive function, dementia, and resilience to Alzheimer’s disease pathology. Cell. DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2023.08.039. (2023).

[2] Xiong X, et al. Epigenomic dissection of Alzheimer’s disease pinpoints causal variants and reveals epigenome erosion. Cell. DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2023.08.040. (2023).

[3] Sun N, et al. Human microglial state dynamics in Alzheimer’s disease progression. Cell. DOIi: 10.1016/j.cell.2023.08.037. (2023).

[4] Dileep V, et al. Neuronal DNA double-strand breaks lead to genome structural variations and 3D genome disruption in neurodegeneration. Cell. 2023 DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2023.08.038. (2023).

NIH Support: National Institute on Aging, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institute of Mental Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences

New Study Points to Targetable Protective Factor in Alzheimer’s Disease

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

If you’ve spent time with individuals affected with Alzheimer’s disease (AD), you might have noticed that some people lose their memory and other cognitive skills more slowly than others. Why is that? New findings indicate that at least part of the answer may lie in differences in their immune responses.

Researchers have now found that slower loss of cognitive skills in people with AD correlates with higher levels of a protein that helps immune cells clear plaque-like cellular debris from the brain [1]. The efficiency of this clean-up process in the brain can be measured via fragments of the protein that shed into the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). This suggests that the protein, called TREM2, and the immune system as a whole, may be promising targets to help fight Alzheimer’s disease.

The findings come from an international research team led by Michael Ewers, Institute for Stroke and Dementia Research, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Germany, and Christian Haass, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Germany and German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases. The researchers got interested in TREM2 following the discovery several years ago that people carrying rare genetic variants for the protein were two to three times more likely to develop AD late in life.

Not much was previously known about TREM2, so this finding from a genome wide association study (GWAS) was a surprise. In the brain, it turns out that TREM2 proteins are primarily made by microglia. These scavenging immune cells help to keep the brain healthy, acting as a clean-up crew that clears cellular debris, including the plaque-like amyloid-beta that is a hallmark of AD.

In subsequent studies, Haass and colleagues showed in mouse models of AD that TREM2 helps to shift microglia into high gear for clearing amyloid plaques [2]. This animal work and that of others helped to strengthen the case that TREM2 may play an important role in AD. But what did these data mean for people with this devastating condition?

There had been some hints of a connection between TREM2 and the progression of AD in humans. In the study published in Science Translational Medicine, the researchers took a deeper look by taking advantage of the NIH-funded Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI).

ADNI began more than a decade ago to develop methods for early AD detection, intervention, and treatment. The initiative makes all its data freely available to AD researchers all around the world. That allowed Ewers, Haass, and colleagues to focus their attention on 385 older ADNI participants, both with and without AD, who had been followed for an average of four years.

Their primary hypothesis was that individuals with AD and evidence of higher TREM2 levels at the outset of the study would show over the years less change in their cognitive abilities and in the volume of their hippocampus, a portion of the brain important for learning and memory. And, indeed, that’s exactly what they found.

In individuals with comparable AD, whether mild cognitive impairment or dementia, those having higher levels of a TREM2 fragment in their CSF showed a slower decline in memory. Those with evidence of a higher ratio of TREM2 relative to the tau protein in their CSF also progressed more slowly from normal cognition to early signs of AD or from mild cognitive impairment to full-blown dementia.

While it’s important to note that correlation isn’t causation, the findings suggest that treatments designed to boost TREM2 and the activation of microglia in the brain might hold promise for slowing the progression of AD in people. The challenge will be to determine when and how to target TREM2, and a great deal of research is now underway to make these discoveries.

Since its launch more than a decade ago, ADNI has made many important contributions to AD research. This new study is yet another fine example that should come as encouraging news to people with AD and their families.

References:

[1] Increased soluble TREM2 in cerebrospinal fluid is associated with reduced cognitive and clinical decline in Alzheimer’s disease. Ewers M, Franzmeier N, Suárez-Calvet M, Morenas-Rodriguez E, Caballero MAA, Kleinberger G, Piccio L, Cruchaga C, Deming Y, Dichgans M, Trojanowski JQ, Shaw LM, Weiner MW, Haass C; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Sci Transl Med. 2019 Aug 28;11(507).

[2] Loss of TREM2 function increases amyloid seeding but reduces plaque-associated ApoE. Parhizkar S, Arzberger T, Brendel M, Kleinberger G, Deussing M, Focke C, Nuscher B, Xiong M, Ghasemigharagoz A, Katzmarski N, Krasemann S, Lichtenthaler SF, Müller SA, Colombo A, Monasor LS, Tahirovic S, Herms J, Willem M, Pettkus N, Butovsky O, Bartenstein P, Edbauer D, Rominger A, Ertürk A, Grathwohl SA, Neher JJ, Holtzman DM, Meyer-Luehmann M, Haass C. Nat Neurosci. 2019 Feb;22(2):191-204.

Links:

Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias (National Institute on Aging/NIH)

Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (University of Southern California, Los Angeles)

Ewers Lab (University Hospital Munich, Germany)

Haass Lab (Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Germany)

German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases (Bonn)

Institute for Stroke and Dementia Research (Munich, Germany)

NIH Support: National Institute on Aging

If I Only Had a Brain? Tissue Chips Predict Neurotoxicity

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

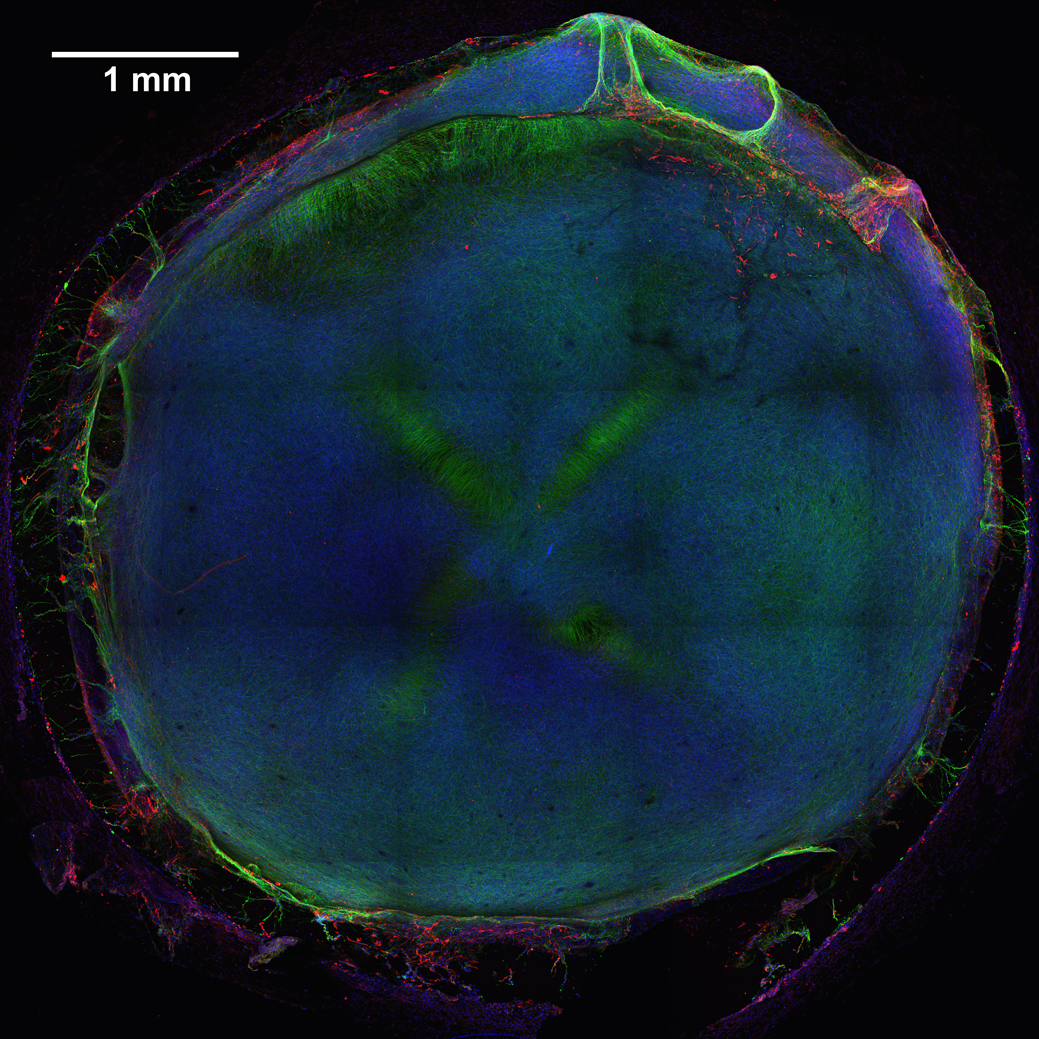

Caption: 3D neural tissue chips contain neurons (green), glial cells (red), and nuclei (blue). To take this confocal micrograph, developing neural tissue was removed from a chip and placed on a glass-bottom Petri dish.

Credit: Michael Schwartz, Dept. of Bioengineering, University of Wisconsin-Madison

A lot of time, money, and effort are devoted to developing new drugs. Yet only one of every 10 drug candidates entering human clinical trials successfully goes on to receive approval from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) [1]. Many would-be drugs fall by the wayside because they prove toxic to the brain, liver, kidneys, or other organs—toxicity that, unfortunately, isn’t always detected in preclinical studies using mice, rats, or other animal models. That explains why scientists are working so hard to devise technologies that can do a better job of predicting early on which chemical compounds will be safe in humans.

As an important step in this direction, NIH-funded researchers at the Morgridge Institute for Research and University of Wisconsin-Madison have produced neural tissue chips with many features of a developing human brain. Each cultured 3D “organoid”—which sits comfortably in the bottom of a pea-sized well on a standard laboratory plate—comes complete with its very own neurons, support cells, blood vessels, and immune cells! As described in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences [2], this new tool is poised to predict earlier, faster, and less expensively which new or untested compounds—be they drug candidates or even ingredients in cosmetics and pesticides—might harm the brain, particularly at the earliest stages of development.