amyloid plaques

Changes in Human Microbiome Precede Alzheimer’s Cognitive Declines

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

In people with Alzheimer’s disease, the underlying changes in the brain associated with dementia typically begin many years—or even decades—before a diagnosis. While pinpointing the exact causes of Alzheimer’s remains a major research challenge, they likely involve a combination of genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors. Now an NIH-funded study elucidates the role of another likely culprit that you may not have considered: the human gut microbiome, the trillions of diverse bacteria and other microbes that live primarily in our intestines [1].

Earlier studies had showed that the gut microbiomes of people with symptomatic Alzheimer’s disease differ from those of healthy people with normal cognition [2]. What this new work advances is that these differences arise early on in people who will develop Alzheimer’s, even before any obvious symptoms appear.

The science still has a ways to go before we’ll know if specific dietary changes can alter the gut microbiome and modify its influence on the brain in the right ways. But what’s exciting about this finding is it raises the possibility that doctors one day could test a patient’s stool sample to determine if what’s present from their gut microbiome correlates with greater early risk for Alzheimer’s dementia. Such a test would help doctors detect Alzheimer’s earlier and intervene sooner to slow or ideally even halt its advance.

The new findings, reported in the journal Science Translational Medicine, come from a research team led by Gautam Dantas and Beau Ances, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis. Ances is a clinician who treats and studies people with Alzheimer’s; Dantas is a basic researcher and expert on the gut microbiome.

The pair struck up a conversation one day about the possible connection between the gut microbiome and Alzheimer’s. While they knew about the earlier studies suggesting a link, they were surprised that nobody had looked at the gut microbiomes of people in the earliest, so-called preclinical, stages of the disease. That’s when dementia isn’t detectable, but the brain has formed amyloid-beta plaques, which are associated with Alzheimer’s.

To take a look, they enrolled 164 healthy volunteers, age 68 to 94, who performed normally on standard tests of cognition. They also collected stool samples from each volunteer and thoroughly analyzed them all the microbes from their gut microbiome. Study participants also kept food diaries and underwent extensive testing, including two types of brain scans, to look for signs of amyloid-beta plaques and tau protein accumulation that precede the onset of Alzheimer’s symptoms.

Among the volunteers, about a third (49 individuals) unfortunately had signs of early Alzheimer’s disease. And, as it turned out, their microbiomes showed differences, too.

The researchers found that those with preclinical Alzheimer’s disease had markedly different assemblages of gut bacteria. Their microbiomes differed in many of the bacterial species present. Those species-level differences also point to differences in the way their microbiomes would be expected to function at a metabolic level. These microbiome changes were observed even though the individuals didn’t seem to have any apparent differences in their diets.

The team also found that the microbiome changes correlated with amyloid-beta and tau levels in the brain. But they did not find any relationship to degenerative changes in the brain, which tend to happen later in people with Alzheimer’s.

The team is now conducting a five-year study that will follow volunteers to get a better handle on whether the differences observed in the gut microbiome are a cause or a consequence of the brain changes seen in Alzheimer’s. If it’s a cause, this discovery would raise the tantalizing possibility that specially formulated probiotics or fecal transplants that promote the growth of “good” bacteria over “bad” bacteria in the gut might slow the development of Alzheimer’s and its most devastating symptoms. It’s an exciting area of research and definitely one worth following in the years ahead.

References:

[1] Gut microbiome composition may be an indicator of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Ferreiro AL, Choi J, Ryou J, Newcomer EP, Thompson R, Bollinger RM, Hall-Moore C, Ndao IM, Sax L, Benzinger TLS, Stark SL, Holtzman DM, Fagan AM, Schindler SE, Cruchaga C, Butt OH, Morris JC, Tarr PI, Ances BM, Dantas G. Sci Transl Med. 2023 Jun 14;15(700):eabo2984. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abo2984. Epub 2023 Jun 14. PMID: 37315112.

[2] Gut microbiome alterations in Alzheimer’s disease. Vogt NM, Kerby RL, Dill-McFarland KA, Harding SJ, Merluzzi AP, Johnson SC, Carlsson CM, Asthana S, Zetterberg H, Blennow K, Bendlin BB, Rey FE. Sci Rep. 2017 Oct 19;7(1):13537. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-13601-y. PMID: 29051531; PMCID: PMC5648830.

Links:

Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias (National Institute on Aging/NIH)

Video: How Alzheimer’s Changes the Brain (NIA)

Dantas Lab (Washington University School of Medicine. St. Louis)

Ances Bioimaging Laboratory (Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis)

NIH Support: National Institute on Aging; National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

New Study Points to Targetable Protective Factor in Alzheimer’s Disease

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

If you’ve spent time with individuals affected with Alzheimer’s disease (AD), you might have noticed that some people lose their memory and other cognitive skills more slowly than others. Why is that? New findings indicate that at least part of the answer may lie in differences in their immune responses.

Researchers have now found that slower loss of cognitive skills in people with AD correlates with higher levels of a protein that helps immune cells clear plaque-like cellular debris from the brain [1]. The efficiency of this clean-up process in the brain can be measured via fragments of the protein that shed into the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). This suggests that the protein, called TREM2, and the immune system as a whole, may be promising targets to help fight Alzheimer’s disease.

The findings come from an international research team led by Michael Ewers, Institute for Stroke and Dementia Research, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Germany, and Christian Haass, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Germany and German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases. The researchers got interested in TREM2 following the discovery several years ago that people carrying rare genetic variants for the protein were two to three times more likely to develop AD late in life.

Not much was previously known about TREM2, so this finding from a genome wide association study (GWAS) was a surprise. In the brain, it turns out that TREM2 proteins are primarily made by microglia. These scavenging immune cells help to keep the brain healthy, acting as a clean-up crew that clears cellular debris, including the plaque-like amyloid-beta that is a hallmark of AD.

In subsequent studies, Haass and colleagues showed in mouse models of AD that TREM2 helps to shift microglia into high gear for clearing amyloid plaques [2]. This animal work and that of others helped to strengthen the case that TREM2 may play an important role in AD. But what did these data mean for people with this devastating condition?

There had been some hints of a connection between TREM2 and the progression of AD in humans. In the study published in Science Translational Medicine, the researchers took a deeper look by taking advantage of the NIH-funded Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI).

ADNI began more than a decade ago to develop methods for early AD detection, intervention, and treatment. The initiative makes all its data freely available to AD researchers all around the world. That allowed Ewers, Haass, and colleagues to focus their attention on 385 older ADNI participants, both with and without AD, who had been followed for an average of four years.

Their primary hypothesis was that individuals with AD and evidence of higher TREM2 levels at the outset of the study would show over the years less change in their cognitive abilities and in the volume of their hippocampus, a portion of the brain important for learning and memory. And, indeed, that’s exactly what they found.

In individuals with comparable AD, whether mild cognitive impairment or dementia, those having higher levels of a TREM2 fragment in their CSF showed a slower decline in memory. Those with evidence of a higher ratio of TREM2 relative to the tau protein in their CSF also progressed more slowly from normal cognition to early signs of AD or from mild cognitive impairment to full-blown dementia.

While it’s important to note that correlation isn’t causation, the findings suggest that treatments designed to boost TREM2 and the activation of microglia in the brain might hold promise for slowing the progression of AD in people. The challenge will be to determine when and how to target TREM2, and a great deal of research is now underway to make these discoveries.

Since its launch more than a decade ago, ADNI has made many important contributions to AD research. This new study is yet another fine example that should come as encouraging news to people with AD and their families.

References:

[1] Increased soluble TREM2 in cerebrospinal fluid is associated with reduced cognitive and clinical decline in Alzheimer’s disease. Ewers M, Franzmeier N, Suárez-Calvet M, Morenas-Rodriguez E, Caballero MAA, Kleinberger G, Piccio L, Cruchaga C, Deming Y, Dichgans M, Trojanowski JQ, Shaw LM, Weiner MW, Haass C; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Sci Transl Med. 2019 Aug 28;11(507).

[2] Loss of TREM2 function increases amyloid seeding but reduces plaque-associated ApoE. Parhizkar S, Arzberger T, Brendel M, Kleinberger G, Deussing M, Focke C, Nuscher B, Xiong M, Ghasemigharagoz A, Katzmarski N, Krasemann S, Lichtenthaler SF, Müller SA, Colombo A, Monasor LS, Tahirovic S, Herms J, Willem M, Pettkus N, Butovsky O, Bartenstein P, Edbauer D, Rominger A, Ertürk A, Grathwohl SA, Neher JJ, Holtzman DM, Meyer-Luehmann M, Haass C. Nat Neurosci. 2019 Feb;22(2):191-204.

Links:

Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias (National Institute on Aging/NIH)

Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (University of Southern California, Los Angeles)

Ewers Lab (University Hospital Munich, Germany)

Haass Lab (Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Germany)

German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases (Bonn)

Institute for Stroke and Dementia Research (Munich, Germany)

NIH Support: National Institute on Aging

Largest-Ever Alzheimer’s Gene Study Brings New Answers

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Predicting whether someone will get Alzheimer’s disease (AD) late in life, and how to use that information for prevention, has been an intense focus of biomedical research. The goal of this work is to learn not only about the genes involved in AD, but how they work together and with other complex biological, environmental, and lifestyle factors to drive this devastating neurological disease.

It’s good news to be able to report that an international team of researchers, partly funded by NIH, has made more progress in explaining the genetic component of AD. Their analysis, involving data from more than 35,000 individuals with late-onset AD, has identified variants in five new genes that put people at greater risk of AD [1]. It also points to molecular pathways involved in AD as possible avenues for prevention, and offers further confirmation of 20 other genes that had been implicated previously in AD.

The results of this largest-ever genomic study of AD suggests key roles for genes involved in the processing of beta-amyloid peptides, which form plaques in the brain recognized as an important early indicator of AD. They also offer the first evidence for a genetic link to proteins that bind tau, the protein responsible for telltale tangles in the AD brain that track closely with a person’s cognitive decline.

The new findings are the latest from the International Genomics of Alzheimer’s Project (IGAP) consortium, led by a large, collaborative team including Brian Kunkle and Margaret Pericak-Vance, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, Miami, FL. The effort, spanning four consortia focused on AD in the United States and Europe, was launched in 2011 with the aim of discovering and mapping all the genes that contribute to AD.

An earlier IGAP study including about 25,500 people with late-onset AD identified 20 common gene variants that influence a person’s risk for developing AD late in life [2]. While that was terrific progress to be sure, the analysis also showed that those gene variants could explain only a third of the genetic component of AD. It was clear more genes with ties to AD were yet to be found.

So, in the study reported in Nature Genetics, the researchers expanded the search. While so-called genome-wide association studies (GWAS) are generally useful in identifying gene variants that turn up often in association with particular diseases or other traits, the ones that arise more rarely require much larger sample sizes to find.

To increase their odds of finding additional variants, the researchers analyzed genomic data for more than 94,000 individuals, including more than 35,000 with a diagnosis of late-onset AD and another 60,000 older people without AD. Their search led them to variants in five additional genes, named IQCK, ACE, ADAM10, ADAMTS1, and WWOX, associated with late-onset AD that hadn’t turned up in the previous study.

Further analysis of those genes supports a view of AD in which groups of genes work together to influence risk and disease progression. In addition to some genes influencing the processing of beta-amyloid peptides and accumulation of tau proteins, others appear to contribute to AD via certain aspects of the immune system and lipid metabolism.

Each of these newly discovered variants contributes only a small amount of increased risk, and therefore probably have limited value in predicting an average person’s risk of developing AD later in life. But they are invaluable when it comes to advancing our understanding of AD’s biological underpinnings and pointing the way to potentially new treatment approaches. For instance, these new data highlight intriguing similarities between early-onset and late-onset AD, suggesting that treatments developed for people with the early-onset form also might prove beneficial for people with the more common late-onset disease.

It’s worth noting that the new findings continue to suggest that the search is not yet over—many more as-yet undiscovered rare variants likely play a role in AD. The search for answers to AD and so many other complex health conditions—assisted through collaborative data sharing efforts such as this one—continues at an accelerating pace.

References:

[1] Genetic meta-analysis of diagnosed Alzheimer’s disease identifies new risk loci and implicates Aβ, tau, immunity and lipid processing. Kunkle BW, Grenier-Boley B, Sims R, Bis JC, et. al. Nat Genet. 2019 Mar;51(3):414-430.

[2] Meta-analysis of 74,046 individuals identifies 11 new susceptibility loci for Alzheimer’s disease. Lambert JC, Ibrahim-Verbaas CA, Harold D, Naj AC, Sims R, Bellenguez C, DeStafano AL, Bis JC, et al. Nat Genet. 2013 Dec;45(12):1452-8.

Links:

Alzheimer’s Disease Genetics Fact Sheet (National Institute on Aging/NIH)

Genome-Wide Association Studies (NIH)

Margaret Pericak-Vance (University of Miami Health System, FL)

NIH Support: National Institute on Aging; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Human Genome Research Institute; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

Alzheimer’s-in-a-Dish: New Tool for Drug Discovery

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: Doo Yeon Kim and Rudolph E. Tanzi, Massachusetts General Hospital/ Harvard Medical School

Researchers want desperately to develop treatments to help the more than 5 million Americans with Alzheimer’s disease and the millions more at risk. But that’s proven to be extremely challenging for a variety of reasons, including the fact that it’s been extraordinarily difficult to mimic the brain’s complexity in standard laboratory models. So, that’s why I was particularly excited by the recent news that an NIH-supported team, led by Rudolph Tanzi at Boston’s Massachusetts General Hospital, has developed a new model called “Alzheimer’s in a dish.”

So, how did Tanzi’s group succeed where others have run up against a brick wall? The answer appears to lie in their decision to add a third dimension to their disease model. Previous attempts at growing human brain cells in the lab and inducing them to form the plaques and tangles characteristic of Alzheimer’s disease were performed in a two-dimensional Petri dish system. And, in this flat, 2-D environment, plaques and tangles simply didn’t appear.

Creative Minds: REST-ling with Alzheimer’s Disease

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

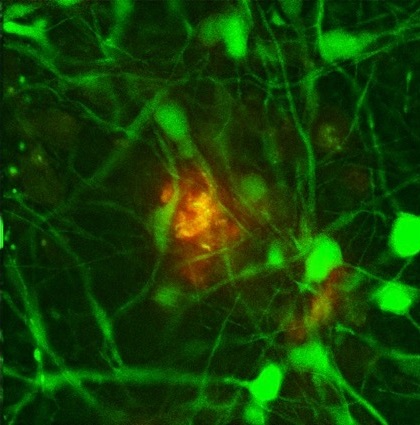

Caption: The REST protein (green) is dormant in young people but switches on in the nucleus of normal aging human neurons (top), apparently providing protection against age-related stresses, including abnormal proteins associated with neurodegenerative diseases. REST is lost in neuron nuclei in critical brain regions in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease (bottom). Neurons are labeled with red.

Credit: Yankner Lab, Harvard Medical School

Why do some people remain mentally sharp over their entire lifetimes, while others develop devastating neurodegenerative diseases that destroy their minds and rob them of their memories? What factors protect the human brain as it ages? And can what we learn about those factors enable us to find ways of helping the millions of people at risk for Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of senile dementia?

Those are just a few of the tough questions that Bruce Yankner, a 2010 recipient of the NIH Director’s Pioneer Award, has set out to answer by monitoring how gene activity in the brain’s prefrontal cortex (PFC) changes as we age. The PFC is the region of the brain involved in decision-making, abstract thinking, working memory, and many other higher cognitive functions; it is also among the regions hardest hit by Alzheimer’s disease.