tau protein

New Findings in Football Players May Aid the Future Diagnosis and Study of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE)

Posted on by Dr. Monica M. Bertagnolli

Repeated hits to the head—whether from boxing, playing American football or experiencing other repetitive head injuries—can increase someone’s risk of developing a serious neurodegenerative condition called chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE). Unfortunately, CTE can only be diagnosed definitively after death during an autopsy of the brain, making it a challenging condition to study and treat. The condition is characterized by tau protein building up in the brain and causes a wide range of problems in thinking, understanding, impulse control, and more. Recent NIH-funded research shows that, alarmingly, even young, amateur players of contact and collision sports can have CTE, underscoring the urgency of finding ways to understand, diagnose, and treat CTE.1

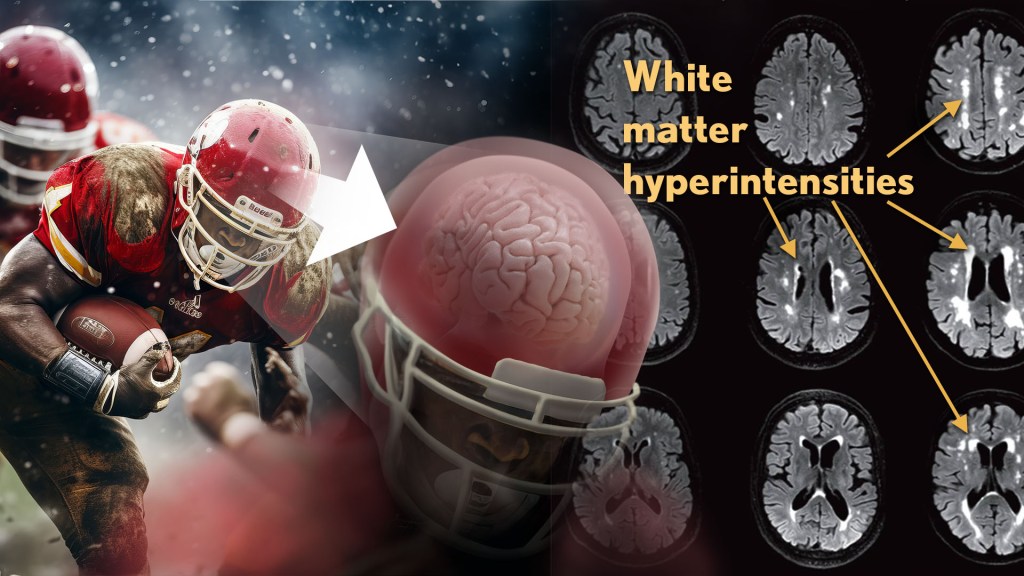

New findings published in the journal Neurology show that increased presence of certain brain lesions that are visible on MRI scans may be related to other brain changes in former football players. The study describes a new way to capture and analyze the long-term impacts of repeated head injuries, which could have implications for understanding signs of CTE. 2

The study analyzes data from the Diagnose CTE Research Project, an NIH-supported effort to develop methods for diagnosing CTE during life and to examine other potential risk factors for the degenerative brain condition. It involves 120 former professional football players and 60 former college football players with an average age of 57. For comparison, it also includes 60 men with an average age of 59 who had no symptoms, did not play football, and had no history of head trauma or concussion.

The new findings link some of the downstream risks of repetitive head impacts to injuries in white matter, the brain’s deeper tissue. Known as white matter hyperintensities (WMH), these injuries show up on MRI scans as easy-to-see bright spots.

Earlier studies had shown that athletes who had experienced repetitive head impacts had an unusual amount of WMH on their brain scans. Those markers, which also show up more as people age normally, are associated with an increased risk for stroke, cognitive decline, dementia and death. In the new study, researchers including Michael Alosco, Boston University Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine, wanted to learn more about WMH and their relationship to other signs of brain trouble seen in former football players.

All the study’s volunteers had brain scans and lumbar punctures to collect cerebrospinal fluid in search of underlying signs or biomarkers of neurodegenerative disease and white matter changes. In the former football players, the researchers found more evidence of WMH. As expected, those with an elevated burden of WMH were more likely to have more risk factors for stroke—such as high blood pressure, hypertension, high cholesterol, and diabetes—but this association was 11 times stronger in former football players than in non-football players. More WMH was also associated with increased concentrations of tau protein in cerebrospinal fluid, and this connection was twice as strong in the football players vs. non-football players. Other signs of functional breakdown in the brain’s white matter were more apparent in participants with increased WMH, and this connection was nearly quadrupled in the former football players.

These latest results don’t prove that WMH from repetitive head impacts cause the other troubling brain changes seen in football players or others who go on to develop CTE. But they do highlight an intriguing association that may aid the further study and diagnosis of repetitive head impacts and CTE, with potentially important implications for understanding—and perhaps ultimately averting—their long-term consequences for brain health.

References:

[1] AC McKee, et al. Neuropathologic and Clinical Findings in Young Contact Sport Athletes Exposed to Repetitive Head Impacts. JAMA Neurology. DOI:10.1001/jamaneurol.2023.2907 (2023).

[2] MT Ly, et al. Association of Vascular Risk Factors and CSF and Imaging Biomarkers With White Matter Hyperintensities in Former American Football Players. Neurology. DOI: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000208030 (2024).

NIH Support: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institute on Aging and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences

Case Study Unlocks Clues to Rare Resilience to Alzheimer’s Disease

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

Biomedical breakthroughs most often involve slow and steady research in studies involving large numbers of people. But sometimes careful study of even just one truly remarkable person can lead the way to fascinating discoveries with far-reaching implications.

An NIH-funded case study published recently in the journal Nature Medicine falls into this far-reaching category [1]. The report highlights the world’s second person known to have an extreme resilience to a rare genetic form of early onset Alzheimer’s disease. These latest findings in a single man follow a 2019 report of a woman with similar resilience to developing symptoms of Alzheimer’s despite having the same strong genetic predisposition for the disease [2].

The new findings raise important new ideas about the series of steps that may lead to Alzheimer’s and its dementia. They’re also pointing the way to key parts of the brain for cognitive resilience—and potentially new treatment targets—that may one day help to delay or even stop progression of Alzheimer’s.

The man in question is a member of a well-studied extended family from the country of Colombia. This group of related individuals, or kindred, is the largest in the world with a genetic variant called the “Paisa” mutation (or Presenilin-1 E280A). This Paisa variant follows an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance, meaning that those with a single altered copy of the rare variant passed down from one parent usually develop mild cognitive impairment around the age of 44. They typically advance to full-blown dementia around the age of 50 and rarely live past the age of 60. This contrasts with the most common form of Alzheimer’s, which usually begins after age 65.

The new findings come from a team led by Yakeel Quiroz, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston; Joseph Arboleda-Velasquez, Massachusetts Eye and Ear, Boston; Diego Sepulveda-Falla, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany; and Francisco Lopera, University of Antioquia, Medellín, Colombia. Lopera first identified this family more than 30 years ago and has been studying them ever since.

In the new case report, the researchers identified a Colombian man who’d been married with two children and retired from his job as a mechanic in his early 60s. Despite carrying the Paisa mutation, his first cognitive assessment at age 67 showed he was cognitively intact, having limited difficulties with verbal learning skills or language. It wasn’t until he turned 70 that he was diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment—more than 20 years later than the expected age for this family—showing some decline in short-term memory and verbal fluency.

At age 73, he enrolled in the Colombia-Boston biomarker research study (COLBOS). This study is a collaborative project between the University of Antioquia and Massachusetts General Hospital involving approximately 6,000 individuals from the Paisa kindred. About 1,500 of those in the study carry the mutation that sets them up for early Alzheimer’s. As a member of the COLBOS study, the man underwent thorough neuroimaging tests to look for amyloid plaques and tau tangles, both of which are hallmarks of Alzheimer’s.

While this man died at age 74 with Alzheimer’s, the big question is: how did he stave off dementia for so long despite his poor genetic odds? The COLBOS study earlier identified a woman with a similar resilience to Alzheimer’s, which they traced to two copies of a rare, protective genetic variant called Christchurch. This variant affects a gene called apolipoprotein E (APOE3), which is well known for its influence on Alzheimer’s risk. However, the man didn’t carry this same protective variant.

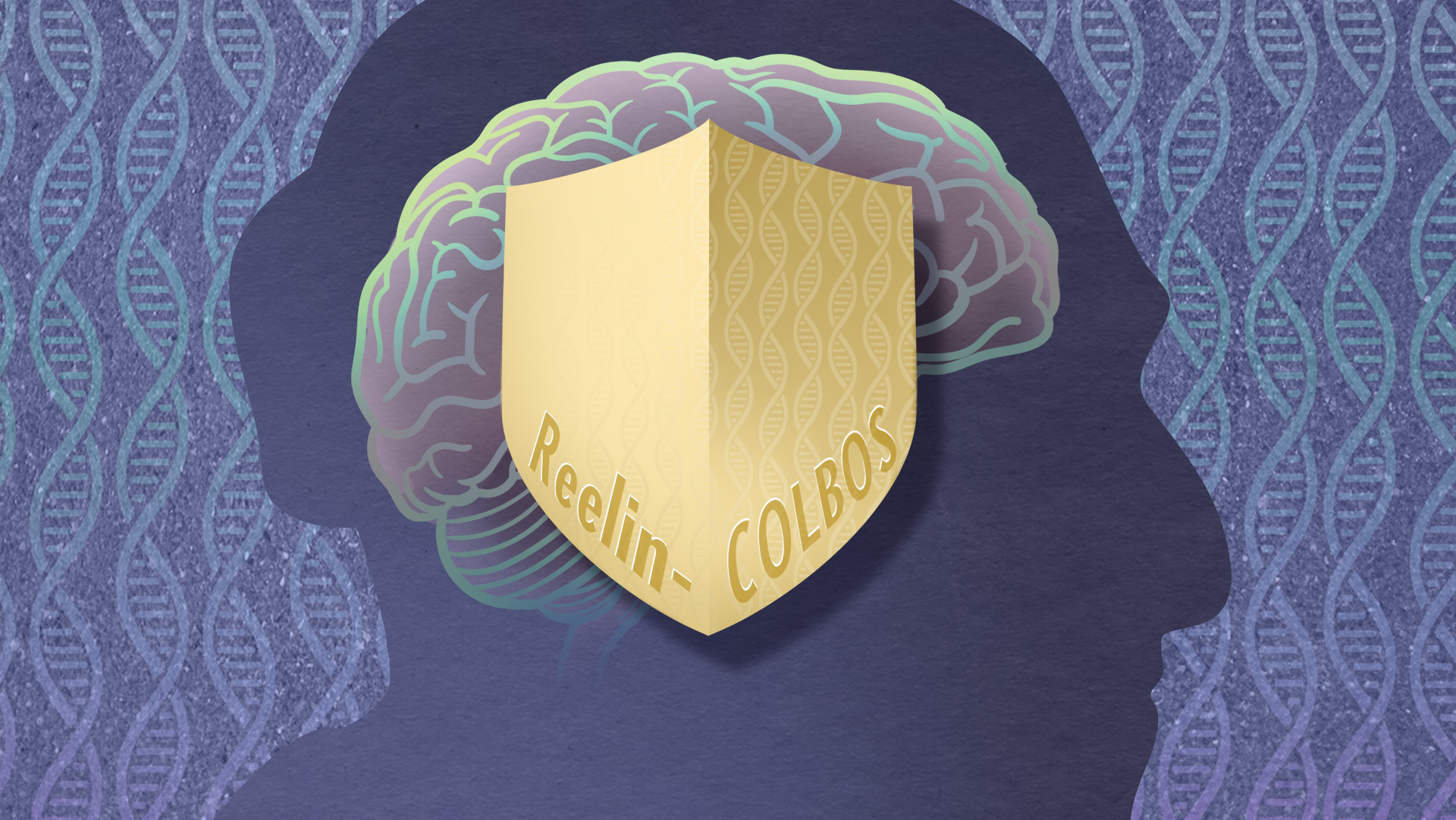

The researchers still thought they’d find an answer in his genome and kept looking. While they found several variants of possible interest, they zeroed in on a single gene variant that they’ve named Reelin-COLBOS. What helped them to narrow it down to this variant is the man also had a sister with the Paisa mutation who only progressed to advanced dementia at age 72. It turned out, in addition to the Paisa variant, the siblings also shared an altered copy of the newly discovered Reelin-COLBOS variant.

This Reelin-COLBOS gene is known to encode a protein that controls signals to chemically modify tau proteins, which form tangles that build up over time in the Alzheimer’s brain and have been linked to memory loss. Reelin is also functionally related to APOE, the gene that was altered in the woman with extreme Alzheimer’s protection. Reelin and APOE both interact with common protein receptors in neurons. Together, the findings add to evidence that signaling pathways influencing tau play an important role in Alzheimer’s pathology and protection.

The neuroimaging exams conducted when the man was age 73 have offered further intriguing clues. They showed that his brain had extensive amyloid plaques. He also had tau tangles in some parts of his brain. But one brain region, called the entorhinal cortex, was notable for having a very minimal amount of those hallmark tau tangles.

The entorhinal cortex is a hub for memory, navigation, and the perception of time. Its degeneration also leads to cognitive impairment and dementia. Studies of the newly identified Reelin-COLBOS variant in Alzheimer’s mouse models also help to confirm that the variant offers its protection by diminishing the pathological modifications of tau.

Overall, the findings in this one individual and his sister highlight the Reelin pathway and brain region as promising targets for future study and development of Alzheimer’s treatments. Quiroz and her colleagues report that they are actively exploring treatment approaches inspired by the Christchurch and Reelin-COLBOS discoveries.

Of course, there’s surely more to discover from continued study of these few individuals and others like them. Other as yet undescribed genetic and environmental factors are likely at play. But the current findings certainly offer some encouraging news for those at risk for Alzheimer’s disease—and a reminder of how much can be learned from careful study of remarkable individuals.

References:

[1] Resilience to autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s disease in a Reelin-COLBOS heterozygous man. Lopera F, Marino C, Chandrahas AS, O’Hare M, Reiman EM, Sepulveda-Falla D, Arboleda-Velasquez JF, Quiroz YT, et al. Nat Med. 2023 May;29(5):1243-1252.

[2] Resistance to autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s disease in an APOE3 Christchurch homozygote: a case report. Arboleda-Velasquez JF, Lopera F, O’Hare M, Delgado-Tirado S, Tariot PN, Johnson KA, Reiman EM, Quiroz YT et al. Nat Med. 2019 Nov;25(11):1680-1683.

Links:

Alzheimer’s Disease & Related Dementias (National Institute on Aging/NIH)

“NIH Support Spurs Alzheimer’s Research in Colombia,” Global Health Matters, January/February 2014, Fogarty International Center/NIS

“COLBOS Study Reveals Mysteries of Alzheimer’s Disease,” NIH Record, August 19, 2022.

Yakeel Quiroz (Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston)

Joseph Arboleda-Velasquez (Massachusetts Eye and Ear, Harvard Medical School, Boston)

Diego Sepulveda-Falla Lab (University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany)

Francisco Lopera (University of Antioquia, Medellín, Colombia)

NIH Support: National Institute on Aging; National Eye Institute; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; Office of the Director

Sleep Loss Encourages Spread of Toxic Alzheimer’s Protein

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

In addition to memory loss and confusion, many people with Alzheimer’s disease have trouble sleeping. Now an NIH-funded team of researchers has evidence that the reverse is also true: a chronic lack of sleep may worsen the disease and its associated memory loss.

The new findings center on a protein called tau, which accumulates in abnormal tangles in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s disease. In the healthy brain, active neurons naturally release some tau during waking hours, but it normally gets cleared away during sleep. Essentially, your brain has a system for taking the garbage out while you’re off in dreamland.

The latest findings in studies of mice and people further suggest that sleep deprivation upsets this balance, allowing more tau to be released, accumulate, and spread in toxic tangles within brain areas important for memory. While more study is needed, the findings suggest that regular and substantial sleep may play an unexpectedly important role in helping to delay or slow down Alzheimer’s disease.

It’s long been recognized that Alzheimer’s disease is associated with the gradual accumulation of beta-amyloid peptides and tau proteins, which form plaques and tangles that are considered hallmarks of the disease. It has only more recently become clear that, while beta-amyloid is an early sign of the disease, tau deposits track more closely with disease progression and a person’s cognitive decline.

Such findings have raised hopes among researchers including David Holtzman, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, that tau-targeting treatments might slow this devastating disease. Though much of the hope has focused on developing the right drugs, some has also focused on sleep and its nightly ability to reset the brain’s metabolic harmony.

In the new study published in Science, Holtzman’s team set out to explore whether tau levels in the brain naturally are tied to the sleep-wake cycle [1]. Earlier studies had shown that tau is released in small amounts by active neurons. But when neurons are chronically activated, more tau gets released. So, do tau levels rise when we’re awake and fall during slumber?

The Holtzman team found that they do. The researchers measured tau levels in brain fluid collected from mice during their normal waking and sleeping hours. (Since mice are nocturnal, they sleep primarily during the day.) The researchers found that tau levels in brain fluid nearly double when the animals are awake. They also found that sleep deprivation caused tau levels in brain fluid to double yet again.

These findings were especially interesting because Holtzman’s team had already made a related finding in people. The team found that healthy adults forced to pull an all-nighter had a 30 percent increase on average in levels of unhealthy beta-amyloid in their cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).

The researchers went back and reanalyzed those same human samples for tau. Sure enough, the tau levels were elevated on average by about 50 percent.

Once tau begins to accumulate in brain tissue, the protein can spread from one brain area to the next along neural connections. So, Holtzman’s team wondered whether a lack of sleep over longer periods also might encourage tau to spread.

To find out, mice engineered to produce human tau fibrils in their brains were made to stay up longer than usual and get less quality sleep over several weeks. Those studies showed that, while less sleep didn’t change the original deposition of tau in the brain, it did lead to a significant increase in tau’s spread. Intriguingly, tau tangles in the animals appeared in the same brain areas affected in people with Alzheimer’s disease.

Another report by Holtzman’s team appearing early last month in Science Translational Medicine found yet another link between tau and poor sleep. That study showed that older people who had more tau tangles in their brains by PET scanning had less slow-wave, deep sleep [2].

Together, these new findings suggest that Alzheimer’s disease and sleep loss are even more intimately intertwined than had been realized. The findings suggest that good sleep habits and/or treatments designed to encourage plenty of high quality Zzzz’s might play an important role in slowing Alzheimer’s disease. On the other hand, poor sleep also might worsen the condition and serve as an early warning sign of Alzheimer’s.

For now, the findings come as an important reminder that all of us should do our best to get a good night’s rest on a regular basis. Sleep deprivation really isn’t a good way to deal with overly busy lives (I’m talking to myself here). It isn’t yet clear if better sleep habits will prevent or delay Alzheimer’s disease, but it surely can’t hurt.

References:

[1] The sleep-wake cycle regulates brain interstitial fluid tau in mice and CSF tau in humans. Holth JK, Fritschi SK, Wang C, Pedersen NP, Cirrito JR, Mahan TE, Finn MB, Manis M, Geerling JC, Fuller PM, Lucey BP, Holtzman DM. Science. 2019 Jan 24.

[2] Reduced non-rapid eye movement sleep is associated with tau pathology in early Alzheimer’s disease. Lucey BP, McCullough A, Landsness EC, Toedebusch CD, McLeland JS, Zaza AM, Fagan AM, McCue L, Xiong C, Morris JC, Benzinger TLS, Holtzman DM. Sci Transl Med. 2019 Jan 9;11(474).

Links:

Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias (National Institute on Aging/NIH)

Accelerating Medicines Partnership: Alzheimer’s Disease (NIH)

Holtzman Lab (Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis)

NIH Support: National Institute on Aging; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences; National Cancer Institute; National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering

Brain Imaging: Tackling Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

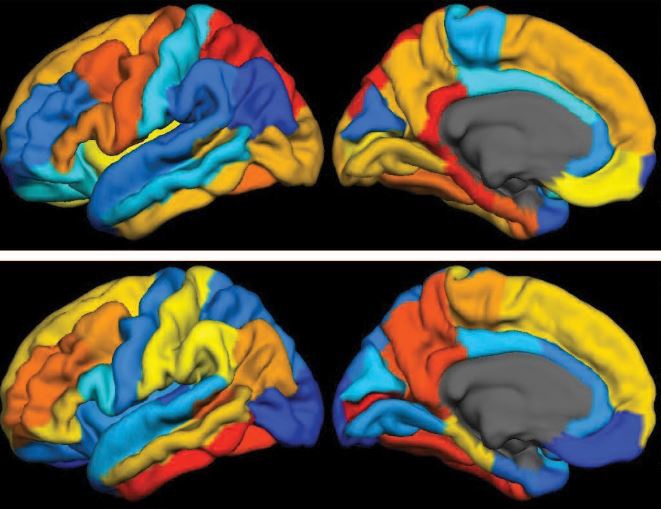

Caption: Left to right, brain PET scans of healthy control; former NFL player with suspected chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE); and person with Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Areas with highest levels of abnormal tau protein appear red/yellow; medium, green; and lowest, blue.

Credit: Adapted from Barrio et al., PNAS

If you follow the National Football League (NFL), you may have heard some former players describe their struggles with a type of traumatic brain injury called chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE). Known to be associated with repeated, hard blows to the head, this neurodegenerative disorder can diminish the ability to think critically, slow motor skills, and lead to volatile, even suicidal, mood swings. What’s doubly frustrating to both patients and physicians is that CTE has only been possible to diagnose conclusively after death (via autopsy) because it’s indistinguishable from many other brain conditions with current imaging methods.

But help might be starting to move out of the backfield toward the goal line of more accurate diagnosis. In findings published in the journal PNAS [1], NIH-supported scientists from the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) and the University of Chicago report they’ve made some progress toward imaging CTE in living people. Following up on their preliminary work published in 2013 [2], the researchers used a specially developed radioactive tracer that lights up a neural protein, called tau, known to deposit in certain areas of the brain in individuals with CTE. They used this approach on PET scans of the brains of 14 former NFL players suspected of having CTE, generating maps of tau distribution throughout various regions of the brain.

Alzheimer’s-in-a-Dish: New Tool for Drug Discovery

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

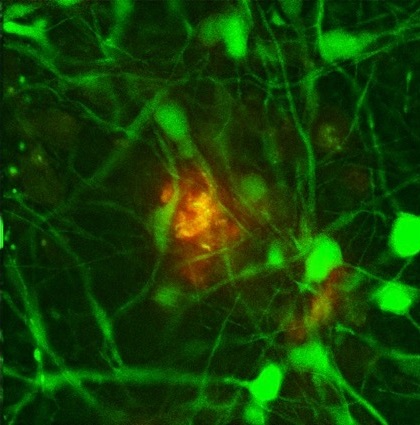

Credit: Doo Yeon Kim and Rudolph E. Tanzi, Massachusetts General Hospital/ Harvard Medical School

Researchers want desperately to develop treatments to help the more than 5 million Americans with Alzheimer’s disease and the millions more at risk. But that’s proven to be extremely challenging for a variety of reasons, including the fact that it’s been extraordinarily difficult to mimic the brain’s complexity in standard laboratory models. So, that’s why I was particularly excited by the recent news that an NIH-supported team, led by Rudolph Tanzi at Boston’s Massachusetts General Hospital, has developed a new model called “Alzheimer’s in a dish.”

So, how did Tanzi’s group succeed where others have run up against a brick wall? The answer appears to lie in their decision to add a third dimension to their disease model. Previous attempts at growing human brain cells in the lab and inducing them to form the plaques and tangles characteristic of Alzheimer’s disease were performed in a two-dimensional Petri dish system. And, in this flat, 2-D environment, plaques and tangles simply didn’t appear.