neurodegenerative

New Findings in Football Players May Aid the Future Diagnosis and Study of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE)

Posted on by Dr. Monica M. Bertagnolli

Repeated hits to the head—whether from boxing, playing American football or experiencing other repetitive head injuries—can increase someone’s risk of developing a serious neurodegenerative condition called chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE). Unfortunately, CTE can only be diagnosed definitively after death during an autopsy of the brain, making it a challenging condition to study and treat. The condition is characterized by tau protein building up in the brain and causes a wide range of problems in thinking, understanding, impulse control, and more. Recent NIH-funded research shows that, alarmingly, even young, amateur players of contact and collision sports can have CTE, underscoring the urgency of finding ways to understand, diagnose, and treat CTE.1

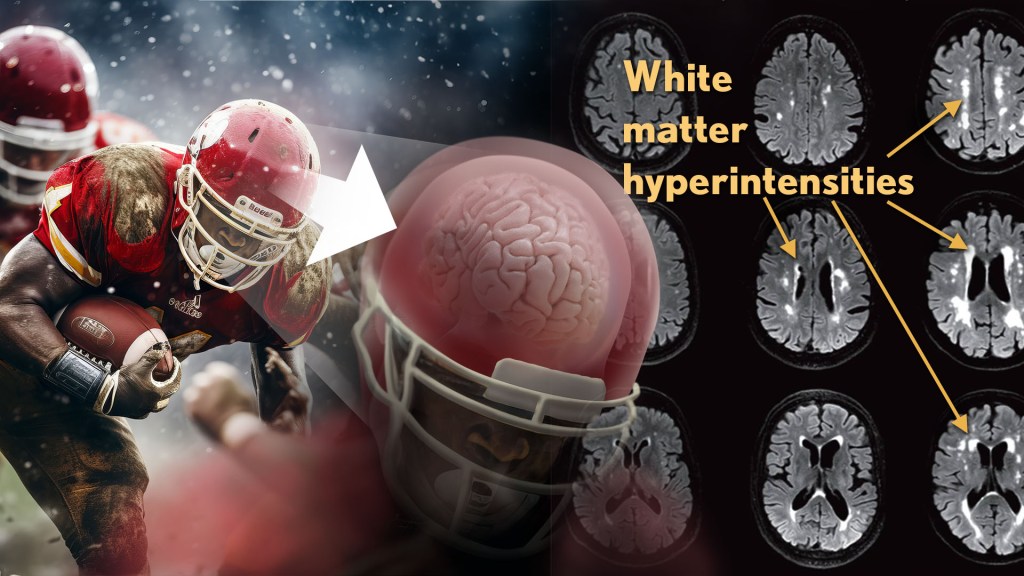

New findings published in the journal Neurology show that increased presence of certain brain lesions that are visible on MRI scans may be related to other brain changes in former football players. The study describes a new way to capture and analyze the long-term impacts of repeated head injuries, which could have implications for understanding signs of CTE. 2

The study analyzes data from the Diagnose CTE Research Project, an NIH-supported effort to develop methods for diagnosing CTE during life and to examine other potential risk factors for the degenerative brain condition. It involves 120 former professional football players and 60 former college football players with an average age of 57. For comparison, it also includes 60 men with an average age of 59 who had no symptoms, did not play football, and had no history of head trauma or concussion.

The new findings link some of the downstream risks of repetitive head impacts to injuries in white matter, the brain’s deeper tissue. Known as white matter hyperintensities (WMH), these injuries show up on MRI scans as easy-to-see bright spots.

Earlier studies had shown that athletes who had experienced repetitive head impacts had an unusual amount of WMH on their brain scans. Those markers, which also show up more as people age normally, are associated with an increased risk for stroke, cognitive decline, dementia and death. In the new study, researchers including Michael Alosco, Boston University Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine, wanted to learn more about WMH and their relationship to other signs of brain trouble seen in former football players.

All the study’s volunteers had brain scans and lumbar punctures to collect cerebrospinal fluid in search of underlying signs or biomarkers of neurodegenerative disease and white matter changes. In the former football players, the researchers found more evidence of WMH. As expected, those with an elevated burden of WMH were more likely to have more risk factors for stroke—such as high blood pressure, hypertension, high cholesterol, and diabetes—but this association was 11 times stronger in former football players than in non-football players. More WMH was also associated with increased concentrations of tau protein in cerebrospinal fluid, and this connection was twice as strong in the football players vs. non-football players. Other signs of functional breakdown in the brain’s white matter were more apparent in participants with increased WMH, and this connection was nearly quadrupled in the former football players.

These latest results don’t prove that WMH from repetitive head impacts cause the other troubling brain changes seen in football players or others who go on to develop CTE. But they do highlight an intriguing association that may aid the further study and diagnosis of repetitive head impacts and CTE, with potentially important implications for understanding—and perhaps ultimately averting—their long-term consequences for brain health.

References:

[1] AC McKee, et al. Neuropathologic and Clinical Findings in Young Contact Sport Athletes Exposed to Repetitive Head Impacts. JAMA Neurology. DOI:10.1001/jamaneurol.2023.2907 (2023).

[2] MT Ly, et al. Association of Vascular Risk Factors and CSF and Imaging Biomarkers With White Matter Hyperintensities in Former American Football Players. Neurology. DOI: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000208030 (2024).

NIH Support: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institute on Aging and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences

New Insight into Parkinson’s Disease

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: Samantha Orenstein and Dr. Esperanza Arias, Department of Developmental and Molecular Biology, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, New York

I’m blogging today to tell you about a new NIH funded report [1] describing a possible cause of Parkinson’s disease: a clog in the protein disposal system.

You probably already know something about Parkinson’s disease. Many of us know individuals who have been stricken, and actor Michael J. Fox, who suffers from it, has done a great job talking about and spreading awareness of it. Parkinson’s is a progressive neurodegenerative condition in which the dopamine-producing cells in the brain region called the substantia nigra begin to sicken and die. These cells are critical for controlling movement; their death causes shaking, difficulty moving, and the characteristic slow gait. Patients can have trouble swallowing, chewing, and speaking. As the disease progresses, cognitive and behavioral problems take hold—depression, personality shifts, sleep disturbances.

A Brain Pacemaker for Alzheimer’s Disease?

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

As many of you know, Alzheimer’s is an absolutely devastating neurodegenerative disease. It destroys the lives of loved ones with the disease, takes a terrible toll on family and friends who care for them, and costs, for patient care alone, an estimated $200 billion a year.

Alzheimer’s is the most common form of dementia, robbing those it affects of their memory, their ability to learn and think, and their personality. It worsens over time. People forget recent events, and gradually lose the ability to manage their daily lives and care for themselves. It currently affects an estimated 5.1 million Americans; this number is expected to rise to somewhere between 11 and 16 million by 2050 unless treatments can be found in the meantime.

There’s no cure for Alzheimer’s disease (AD), but biomedical researchers are testing new drugs and biochemical approaches, treatments that could stem and possibly reverse the course of the disease. They are also exploring how conditions like obesity and diabetes—which are at epidemic levels in the U.S. and worldwide—play a role. I want to tell you about a new NIH-funded experimental approach that was tried for the first time in the U.S. in November.

Neurosurgeons at Johns Hopkins Hospital, in Baltimore, MD, implanted a ‘pacemaker’ in the brain of a patient with mild AD. You are probably familiar with the concept of a pacemaker that stabilizes heart rhythms. The implanted device sends electrical pulses to the heart muscle, resetting a normal heartbeat. In some ways, this pacemaker for AD is similar. It, too, sends electrical pulses, but targets a region of the brain called the fornix—a bundle of 1.2 million axons that normally serves as a superhighway for learning, emotion, and forming memories. The fornix is one of the first regions to be destroyed by Alzheimer’s.