New Findings in Football Players May Aid the Future Diagnosis and Study of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE)

Posted on by Dr. Monica M. Bertagnolli

Repeated hits to the head—whether from boxing, playing American football or experiencing other repetitive head injuries—can increase someone’s risk of developing a serious neurodegenerative condition called chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE). Unfortunately, CTE can only be diagnosed definitively after death during an autopsy of the brain, making it a challenging condition to study and treat. The condition is characterized by tau protein building up in the brain and causes a wide range of problems in thinking, understanding, impulse control, and more. Recent NIH-funded research shows that, alarmingly, even young, amateur players of contact and collision sports can have CTE, underscoring the urgency of finding ways to understand, diagnose, and treat CTE.1

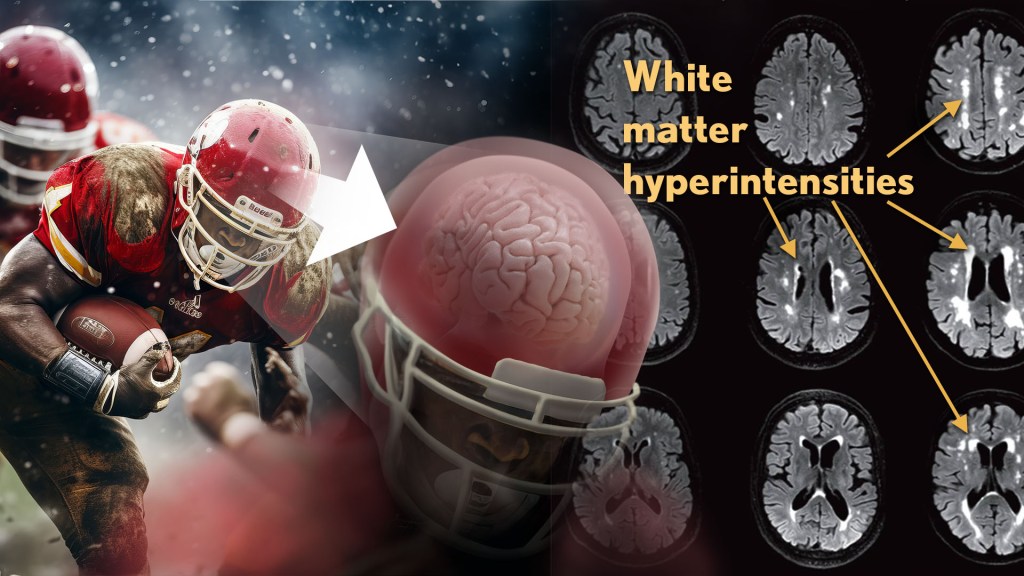

New findings published in the journal Neurology show that increased presence of certain brain lesions that are visible on MRI scans may be related to other brain changes in former football players. The study describes a new way to capture and analyze the long-term impacts of repeated head injuries, which could have implications for understanding signs of CTE. 2

The study analyzes data from the Diagnose CTE Research Project, an NIH-supported effort to develop methods for diagnosing CTE during life and to examine other potential risk factors for the degenerative brain condition. It involves 120 former professional football players and 60 former college football players with an average age of 57. For comparison, it also includes 60 men with an average age of 59 who had no symptoms, did not play football, and had no history of head trauma or concussion.

The new findings link some of the downstream risks of repetitive head impacts to injuries in white matter, the brain’s deeper tissue. Known as white matter hyperintensities (WMH), these injuries show up on MRI scans as easy-to-see bright spots.

Earlier studies had shown that athletes who had experienced repetitive head impacts had an unusual amount of WMH on their brain scans. Those markers, which also show up more as people age normally, are associated with an increased risk for stroke, cognitive decline, dementia and death. In the new study, researchers including Michael Alosco, Boston University Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine, wanted to learn more about WMH and their relationship to other signs of brain trouble seen in former football players.

All the study’s volunteers had brain scans and lumbar punctures to collect cerebrospinal fluid in search of underlying signs or biomarkers of neurodegenerative disease and white matter changes. In the former football players, the researchers found more evidence of WMH. As expected, those with an elevated burden of WMH were more likely to have more risk factors for stroke—such as high blood pressure, hypertension, high cholesterol, and diabetes—but this association was 11 times stronger in former football players than in non-football players. More WMH was also associated with increased concentrations of tau protein in cerebrospinal fluid, and this connection was twice as strong in the football players vs. non-football players. Other signs of functional breakdown in the brain’s white matter were more apparent in participants with increased WMH, and this connection was nearly quadrupled in the former football players.

These latest results don’t prove that WMH from repetitive head impacts cause the other troubling brain changes seen in football players or others who go on to develop CTE. But they do highlight an intriguing association that may aid the further study and diagnosis of repetitive head impacts and CTE, with potentially important implications for understanding—and perhaps ultimately averting—their long-term consequences for brain health.

References:

[1] AC McKee, et al. Neuropathologic and Clinical Findings in Young Contact Sport Athletes Exposed to Repetitive Head Impacts. JAMA Neurology. DOI:10.1001/jamaneurol.2023.2907 (2023).

[2] MT Ly, et al. Association of Vascular Risk Factors and CSF and Imaging Biomarkers With White Matter Hyperintensities in Former American Football Players. Neurology. DOI: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000208030 (2024).

NIH Support: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institute on Aging and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences

Is this with NeuroQuant Imaging? Anyone know what type of MRI (or with applied program), there are so many different programs to apply which need to be on the MRI Order prior to getting to the MRI – for example the NeuroQuant program. Some locations don’t offer all programs.

I would assume this may not just be limited to football players and blunt force trauma either? Has anyone done any detailed scans of the US Embassy employees with various un-diagnosed ailments in Cuba? Is tau a by product of brain injury rather than the cause? Just like cardiac troponin is not the the cause of myocardial infarction, but rather a biomarker? When PhII clinical trial outcomes are designed with biomarkers, that aspect of clinical utility is not always delineated given the complexities of MOA and also explains the higher failure rates in PhIII studies.

This country puts itself at a disadvantage when lay people who do not understand science take it over to drive the narrative. Something that many scientists involved with the Manhattan Project were well aware of. Perhaps some of these issues require Broadway worthy shows for the Davos crowd who make decisions for the vast majority of the population?

This article brings us to the issue of why our kids are dying before they are 30. Thanks to Dr. Ann McKee, who is capable of finding this CTE in the brain, we know we need to pay attention when the Boston University CTE Clinic is talking.