COVID-19 infections

How One Change to The Coronavirus Spike Influences Infectivity

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

Since joining NIH, I’ve held a number of different leadership positions. But there is one position that thankfully has remained constant for me: lab chief. I run my own research laboratory at NIH’s National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR).

My lab studies a biochemical process called O-glycosylation. It’s fundamental to life and fascinating to study. Our cells are often adorned with a variety of carbohydrate sugars. O-glycosylation refers to the biochemical process through which these sugar molecules, either found at the cell surface or secreted, get added to proteins. The presence or absence of these sugars on certain proteins plays fundamental roles in normal tissue development and first-line human immunity. It also is associated with various diseases, including cancer.

Our lab recently joined a team of NIH scientists led by my NIDCR colleague Kelly Ten Hagen to demonstrate how O-glycosylation can influence SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, and its ability to fuse to cells, which is a key step in infecting them. In fact, our data, published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, indicate that some variants, seem to have mutated to exploit the process to their advantage [1].

The work builds on the virus’s reliance on the spike proteins that crown its outer surface to attach to human cells. Once there, the spike protein must be activated to fuse and launch an infection. That happens when enzymes produced by our own cells make a series of cuts, or cleavages, to the spike protein.

The first cut comes from an enzyme called furin. We and others had earlier evidence that O-glycosylation can affect the way furin makes those cuts. That got us thinking: Could O-glycosylation influence the interaction between furin and the spike protein? The furin cleavage area of the viral spike was indeed adorned with sugars, and their presence or absence might influence spike activation by furin.

We also noticed the Alpha and Delta variants carry a mutation that removes the amino acid proline in a specific spot. That was intriguing because we knew from earlier work that enzymes called GALNTs, which are responsible for adding bulky sugar molecules to proteins, prefer prolines near O-glycosylation sites.

It also suggested that loss of proline in the new variants could mean decreased O-glycosylation, which might then influence the degree of furin cleavage and SARS-CoV-2’s ability to enter cells. I should note that the recent Omicron variant was not examined in the current study.

After detailed studies in fruit fly and mammalian cells, we demonstrated in the original SARS-CoV-2 virus that O-glycosylation of the spike protein decreases furin cleavage. Further experiments then showed that the GALNT1 enzyme adds sugars to the spike protein and this addition limits the ability of furin to make the needed cuts and activate the spike protein.

Importantly, the spike protein change found in the Alpha and Delta variants lowers GALNT1 activity, making it easier for furin to start its activating cuts. It suggests that glycosylation of the viral spike by GALNT1 may limit infection with the original virus, and that the Alpha and Delta variant mutation at least partially overcomes this effect, to potentially make the virus more infectious.

Building on these studies, our teams looked for evidence of GALNT1 in the respiratory tracts of healthy human volunteers. We found that the enzyme is indeed abundantly expressed in those cells. Interestingly, those same cells also express the ACE2 receptor, which SARS-CoV-2 depends on to infect human cells.

It’s also worth noting here that the Omicron variant carries the very same spike mutation that we studied in Alpha and Delta. Omicron also has another nearby change that might further alter O-glycosylation and cleavage of the spike protein by furin. The Ten Hagen lab is looking into these leads to learn how this region in Omicron affects spike glycosylation and, ultimately, the ability of this devastating virus to infect human cells and spread.

Reference:

[1] Furin cleavage of the SARS-CoV-2 spike is modulated by O-glycosylation. Zhang L, Mann M, Syed Z, Reynolds HM, Tian E, Samara NL, Zeldin DC, Tabak LA, Ten Hagen KG. PNAS. 2021 Nov 23;118(47).

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Kelly Ten Hagen (National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research/NIH)

Lawrence Tabak (NIDCR)

NIH Support: National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research

Breakthrough Infections Occur in Those with Lower Antibody Levels, Israeli Study Shows

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

To see how COVID-19 vaccines are working in the real world, Israel has provided particularly compelling data. The fact that Israel is relatively small, keeps comprehensive medical records, and has a high vaccination rate with a single vaccine (Pfizer) has contributed to its robust data collection. Now, a new Israeli study offers some insight into those relatively uncommon breakthrough infections. It confirms that breakthrough cases, as might be expected, arise most often in individuals with lower levels of neutralizing antibodies.

The findings reported in The New England Journal of Medicine focused on nearly 1,500 of about 11,500 fully vaccinated health care workers at Sheba Medical Center, Ramat Gan, Israel [1]. All had received two doses of the Pfizer mRNA vaccine. But, from December 19, 2020 to April 28, 2021, they were tested for a breakthrough infection due to a known exposure to someone with COVID-19 or possible symptoms of the disease.

Just 39 confirmed breakthrough cases were found, indicating a breakthrough infection rate of just 0.4 percent. That’s consistent with rates reported in previous studies. Most in the Israeli study who tested positive for COVID-19 had mild or no symptoms and none required hospitalization.

In the new study, researchers led by Gili Regev-Yochay at Sheba Medical Center’s Infection Control and Prevention Unit, characterized as many breakthrough infections as possible among the health care workers. Almost half of the infections involved members of the hospital nursing staff. But breakthrough cases also were found in hospital administration, maintenance workers, doctors, and other health professionals.

The average age of someone with a breakthrough infection was 42, and it’s notable that only one person was known to have a weakened immune system. The most common symptoms were respiratory congestion, muscle aches (myalgia), and loss of smell or taste. Most didn’t develop a fever. At six weeks after diagnosis, 19 percent reported having symptoms of Long COVID syndrome, including prolonged loss of smell, persistent cough, weakness, and fatigue. About a quarter stayed home from work for longer than the required 10 days, and one had yet to return to work at six weeks.

For 22 of the 39 people with a breakthrough infection, the researchers had results of neutralizing antibody tests from the week leading up to their positive COVID-19 test result. To look for patterns in the antibody data, they matched those individuals to 104 uninfected people for whom they also had antibody test results. These data showed that those with a breakthrough infection had consistently lower levels of neutralizing antibodies circulating in their bloodstream to SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19. In general, higher levels of neutralizing antibodies are associated with greater protection and lower infectivity—though other aspects of the immune system (memory B cells and cell-mediated immunity) also contribute.

Importantly, in all cases for which there were relevant data, the source of the breakthrough infection was thought to be an unvaccinated person. In fact, more than half of those who developed a breakthrough infection appeared to have become infected from an unvaccinated member of their own household.

Other cases were suspected to arise from exposure to an unvaccinated coworker or patient. Contact tracing found no evidence that any of the 39 health care workers with a breakthrough infection passed it on to anyone else.

The findings add to evidence that full vaccination and associated immunity offer good protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection and severe illness. Understanding how SARS-CoV-2 immunity changes over time is key for charting the course of this pandemic and making important decisions about COVID-19 vaccine boosters.

Many questions remain. For instance, it’s not clear from the study whether lower neutralizing antibodies in those with breakthrough cases reflect waning immunity or, for reasons we don’t yet understand, those individuals may have had a more limited immune response to the vaccine. Also, this study was conducted before the Delta variant became dominant in Israel (and now in the whole world).

Overall, these findings provide more reassurance that these vaccines are extremely effective. Breakthrough infections, while they can and do occur, are a relatively uncommon event. Here in the U.S., the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has recently estimated that infection is six times less likely for vaccinated than unvaccinated persons [2]. That those with immunity tend to have mild or no symptoms if they do develop a breakthrough case, however, is a reminder that these cases could easily be missed, and they could put vulnerable populations at greater risk. It’s yet another reason for all those who can to get themselves vaccinated as soon as possible or consider a booster shot when they become eligible.

References:

[1] Covid-19 breakthrough infections in vaccinated health care workers. Bergwerk M, Gonen T, Lustig Y, Amit S, Lipsitch M, Cohen C, Mandelboim M, Levin EG, Rubin C, Indenbaum V, Tal I, Zavitan M, Zuckerman N, Bar-Chaim A, Kreiss Y, Regev-Yochay G. N Engl J Med. 2021 Oct 14;385(16):1474-1484.

[2] Rates of COVID-19 cases and deaths by vaccination status, COVID Data Tracker, Centers for Disease and Prevention. Accessed October 25, 2021.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Sheba Medical Center (Ramat Gan, Israel)

COVID-19 Vaccines Protect the Family, Too

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Any of the available COVID-19 vaccines offer remarkable personal protection against the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. So, it also stands to reason that folks who are vaccinated will reduce the risk of spreading the virus to family members within their households. That protection is particularly important when not all family members can be immunized—as when there are children under age 12 or adults with immunosuppression in the home. But just how much can vaccines help to protect families from COVID-19 when only some, not all, in the household have immunity?

A Swedish study, published recently in the journal JAMA Internal Medicine, offers some of the first hard figures on this topic, and the findings are quite encouraging [1]. The data show that people without any immunity against COVID-19 were at considerably lower risk of infection and hospitalization when other members of their family had immunity, either from a natural infection or vaccination. In fact, the protective effect on family members went up as the number of immune family members increased.

The findings come from a team led by Peter Nordström, Umeå University, Sweden. Like in the United States, vaccinations in Sweden initially were prioritized for high-risk groups and people with certain preexisting conditions. As a result, Swedish families have functioned, often in close contact, as a mix of immune and susceptible individuals over the course of the pandemic.

To explore these family dynamics in greater detail, the researchers relied on nationwide registries to identify all Swedes who had immunity to SARS-COV-2 from either a confirmed infection or vaccination by May 26, 2021. The researchers identified more than 5 million individuals who’d been either diagnosed with COVID-19 or vaccinated and then matched them to a control group without immunity. They also limited the analysis to individuals in families with two to five members of mixed immune status.

This left them with about 1.8 million people from more than 800,000 families. The situation in Sweden is also a little unique from most Western nations. Somewhat controversially, the Swedish government didn’t order a mandatory citizen quarantine to slow the spread of the virus.

The researchers found in the data a rising protective effect for those in the household without immunity as the number of immune family members increased. Families with one immune family member had a 45 to 61 percent lower risk of a COVID-19 infection in the home than those who had none. Those with two immune family members enjoyed more protection, with a 75 to 86 percent reduction in risk of COVID-19. For those with three or four immune family members, the protection went up to more than 90 percent, topping out at 97 percent protection. The results were similar when the researchers limited the analysis to COVID-19 illnesses serious enough to warrant a hospital stay.

The findings confirm that vaccination is incredibly important not only for individual protection, but also for reducing transmission, especially within families and those with whom we’re in close physical contact. It’s also important to note that the findings apply to the original SARS-CoV-2 variant, which was dominant when the study was conducted. But we know that the vaccines offer good protection against Delta and other variants of concern.

These results show quite clearly that vaccines offer protection for individuals who lack immunity, with important implications for finally ending this pandemic. This doesn’t change the fact that all those who can and still need to get fully vaccinated should do so as soon as possible. If you are eligible for a booster shot, that’s something to consider, too. But, if for whatever reason you haven’t gotten vaccinated just yet, perhaps these new findings will encourage you to do it now for the sake of those other people you care about. This is a chance to love your family—and love your neighbor.

Reference:

[1] Association between risk of COVID-19 infection in nonimmune individuals and COVID-19 immunity in their family members. Nordström P, Ballin M, Nordström A. JAMA Intern Med. 2021 Oct 11.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Peter Nordström (Umeå University, Sweden)

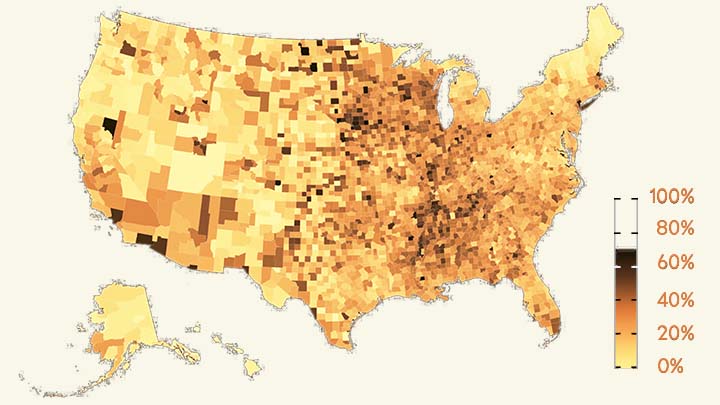

COVID-19 Infected Many More Americans in 2020 than Official Tallies Show

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

At the end of last year, you may recall hearing news reports that the number of COVID-19 cases in the United States had topped 20 million. While that number came as truly sobering news, it also likely was an underestimate. Many cases went undetected due to limited testing early in the year and a large number of infections that produced mild or no symptoms.

Now, a recent article published in Nature offers a more-comprehensive estimate that puts the true number of infections by the end of 2020 at more than 100 million [1]. That’s equal to just under a third of the U.S. population of 328 million. This revised number shows just how rapidly this novel coronavirus spread through the country last year. It also brings home just how timely the vaccines have been—and continue to be in 2021—to protect our nation’s health in this time of pandemic.

The work comes from NIH grantee Jeffrey Shaman, Sen Pei, and colleagues, Columbia University, New York. As shown above in the map, the researchers estimated the percentage of people who had been infected with SARS-CoV-2, the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19, in communities across the country through December 2020.

To generate this map, they started with existing national data on the number of coronavirus cases (both detected and undetected) in 3,142 U.S. counties and major metropolitan areas. They then factored in data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) on the number of people who tested positive for antibodies against SARS-CoV-2. These CDC data are useful for picking up on past infections, including those that went undetected.

From these data, the researchers calculated that only about 11 percent of all COVID-19 cases were confirmed by a positive test result in March 2020. By the end of the year, with testing improvements and heightened public awareness of COVID-19, the ascertainment rate (the number of infections that were known versus unknown) rose to about 25 percent on average. This measure also varied a lot across the country. For instance, the ascertainment rates in Miami and Phoenix were higher than the national average, while rates in New York City, Los Angeles, and Chicago were lower than average.

How many people were potentially walking around with a contagious SARS-CoV-2 infection? The model helps to answer this, too. On December 31, 2020, the researchers estimate that 0.77 percent of the U.S. population had a contagious infection. That’s about 1 in every 130 people on average. In some places, it was much higher. In Los Angeles, for example, nearly 1 in 40 (or 2.42 percent) had a SARS-CoV-2 infection as they rang in the New Year.

Over the course of the year, the fatality rate associated with COVID-19 dropped, at least in part due to earlier diagnosis and advances in treatment. The fatality rate went from 0.77 percent in April to 0.31 percent in December. While this is great news, it still shows that COVID-19 remains much more dangerous than seasonal influenza (which has a fatality rate of 0.08 percent).

Today, the landscape has changed considerably. Vaccines are now widely available, giving many more people immune protection without ever having to get infected. And yet, the rise of the Delta and other variants means that breakthrough infections and reinfections—which the researchers didn’t account for in their model—have become a much bigger concern.

Looking ahead to the end of 2021, Americans must continue to do everything they can to protect their communities from the spread of this terrible virus. That means getting vaccinated if you haven’t already, staying home and getting tested if you’ve got symptoms or know of an exposure, and taking other measures to keep yourself and your loved ones safe and well. These measures we take now will influence the infection rates and susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 in our communities going forward. That will determine what the map of SARS-CoV-2 infections will look like in 2021 and beyond and, ultimately, how soon we can finally put this pandemic behind us.

Reference:

[1] Burden and characteristics of COVID-19 in the United States during 2020. Pei S, Yamana TK, Kandula S, Galanti M, Shaman J. Nature. 2021 Aug 26.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Sen Pei (Columbia University, New York)

Jeffrey Shaman (Columbia University, New York)

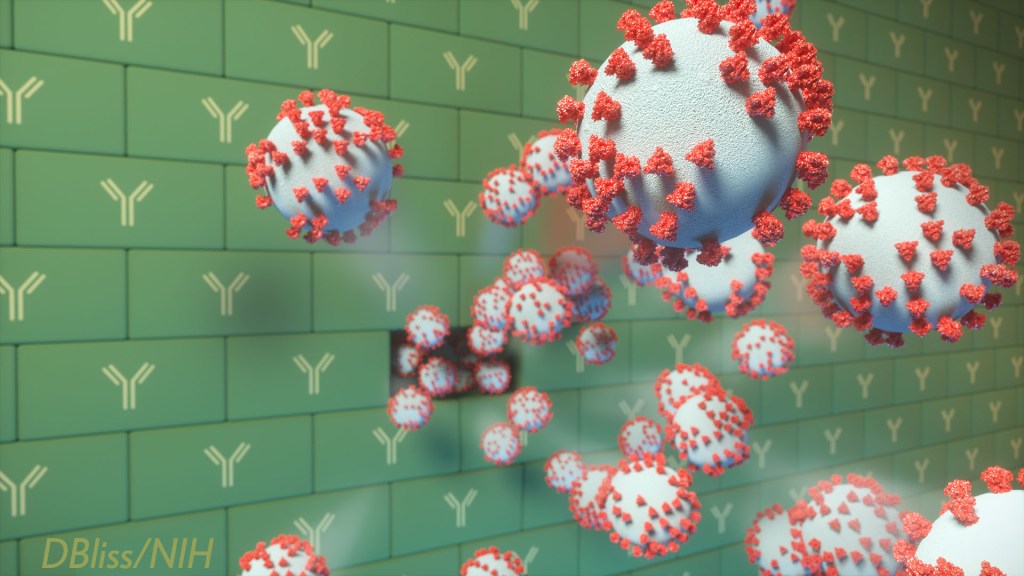

How Immunity Generated from COVID-19 Vaccines Differs from an Infection

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

A key issue as we move closer to ending the pandemic is determining more precisely how long people exposed to SARS-CoV-2, the COVID-19 virus, will make neutralizing antibodies against this dangerous coronavirus. Finding the answer is also potentially complicated with new SARS-CoV-2 “variants of concern” appearing around the world that could find ways to evade acquired immunity, increasing the chances of new outbreaks.

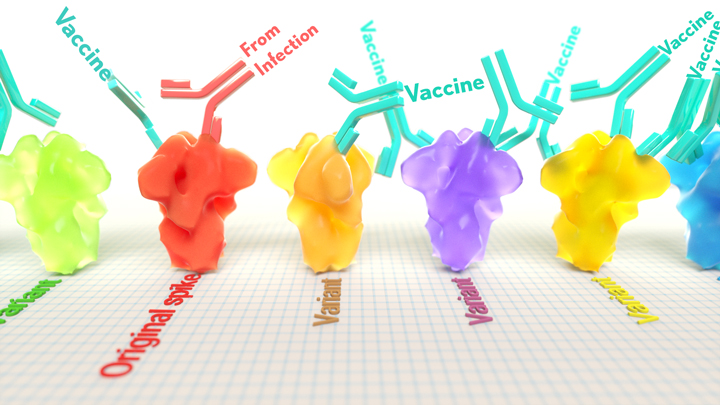

Now, a new NIH-supported study shows that the answer to this question will vary based on how an individual’s antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 were generated: over the course of a naturally acquired infection or from a COVID-19 vaccine. The new evidence shows that protective antibodies generated in response to an mRNA vaccine will target a broader range of SARS-CoV-2 variants carrying “single letter” changes in a key portion of their spike protein compared to antibodies acquired from an infection.

These results add to evidence that people with acquired immunity may have differing levels of protection to emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants. More importantly, the data provide further documentation that those who’ve had and recovered from a COVID-19 infection still stand to benefit from getting vaccinated.

These latest findings come from Jesse Bloom, Allison Greaney, and their team at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle. In an earlier study, this same team focused on the receptor binding domain (RBD), a key region of the spike protein that studs SARS-CoV-2’s outer surface. This RBD is especially important because the virus uses this part of its spike protein to anchor to another protein called ACE2 on human cells before infecting them. That makes RBD a prime target for both naturally acquired antibodies and those generated by vaccines. Using a method called deep mutational scanning, the Seattle group’s previous study mapped out all possible mutations in the RBD that would change the ability of the virus to bind ACE2 and/or for RBD-directed antibodies to strike their targets.

In their new study, published in the journal Science Translational Medicine, Bloom, Greaney, and colleagues looked again to the thousands of possible RBD variants to understand how antibodies might be expected to hit their targets there [1]. This time, they wanted to explore any differences between RBD-directed antibodies based on how they were acquired.

Again, they turned to deep mutational scanning. First, they created libraries of all 3,800 possible RBD single amino acid mutants and exposed the libraries to samples taken from vaccinated individuals and unvaccinated individuals who’d been previously infected. All vaccinated individuals had received two doses of the Moderna mRNA vaccine. This vaccine works by prompting a person’s cells to produce the spike protein, thereby launching an immune response and the production of antibodies.

By closely examining the results, the researchers uncovered important differences between acquired immunity in people who’d been vaccinated and unvaccinated people who’d been previously infected with SARS-CoV-2. Specifically, antibodies elicited by the mRNA vaccine were more focused to the RBD compared to antibodies elicited by an infection, which more often targeted other portions of the spike protein. Importantly, the vaccine-elicited antibodies targeted a broader range of places on the RBD than those elicited by natural infection.

These findings suggest that natural immunity and vaccine-generated immunity to SARS-CoV-2 will differ in how they recognize new viral variants. What’s more, antibodies acquired with the help of a vaccine may be more likely to target new SARS-CoV-2 variants potently, even when the variants carry new mutations in the RBD.

It’s not entirely clear why these differences in vaccine- and infection-elicited antibody responses exist. In both cases, RBD-directed antibodies are acquired from the immune system’s recognition and response to viral spike proteins. The Seattle team suggests these differences may arise because the vaccine presents the viral protein in slightly different conformations.

Also, it’s possible that mRNA delivery may change the way antigens are presented to the immune system, leading to differences in the antibodies that get produced. A third difference is that natural infection only exposes the body to the virus in the respiratory tract (unless the illness is very severe), while the vaccine is delivered to muscle, where the immune system may have an even better chance of seeing it and responding vigorously.

Whatever the underlying reasons turn out to be, it’s important to consider that humans are routinely infected and re-infected with other common coronaviruses, which are responsible for the common cold. It’s not at all unusual to catch a cold from seasonal coronaviruses year after year. That’s at least in part because those viruses tend to evolve to escape acquired immunity, much as SARS-CoV-2 is now in the process of doing.

The good news so far is that, unlike the situation for the common cold, we have now developed multiple COVID-19 vaccines. The evidence continues to suggest that acquired immunity from vaccines still offers substantial protection against the new variants now circulating around the globe.

The hope is that acquired immunity from the vaccines will indeed produce long-lasting protection against SARS-CoV-2 and bring an end to the pandemic. These new findings point encouragingly in that direction. They also serve as an important reminder to roll up your sleeve for the vaccine if you haven’t already done so, whether or not you’ve had COVID-19. Our best hope of winning this contest with the virus is to get as many people immunized now as possible. That will save lives, and reduce the likelihood of even more variants appearing that might evade protection from the current vaccines.

Reference:

[1] Antibodies elicited by mRNA-1273 vaccination bind more broadly to the receptor binding domain than do those from SARS-CoV-2 infection. Greaney AJ, Loes AN, Gentles LE, Crawford KHD, Starr TN, Malone KD, Chu HY, Bloom JD. Sci Transl Med. 2021 Jun 8.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Bloom Lab (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle)

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

Study of Healthcare Workers Shows COVID-19 Immunity Lasts Many Months

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, healthcare workers around the world have shown willingness to put their own lives on the line for their patients and communities. Unfortunately, many have also contracted SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes of COVID-19, while caring for patients. That makes these frontline heroes helpful in another way in the fight against SARS-CoV-2: determining whether people who have recovered from COVID-19 can be reinfected by the virus.

New findings from a study of thousands of healthcare workers in England show that those who got COVID-19 and produced antibodies against the virus are highly unlikely to become infected again, at least over the several months that the study was conducted. In the rare instances in which someone with acquired immunity for SARS-CoV-2 subsequently tested positive for the virus within a six month period, they never showed any signs of being ill.

Some earlier studies have shown that people who survive a COVID-19 infection continue to produce protective antibodies against key parts of the virus for several months. But how long those antibodies last and whether they are enough to protect against reinfection have remained open questions.

In search of answers, researchers led by David Eyre, University of Oxford, England, looked to more than 12,000 healthcare workers at Oxford University Hospitals from April to November 2020. At the start of the study, 11,052 of them tested negative for antibodies against SARS-CoV-2, suggesting they hadn’t had COVID-19. But the other 1,246 tested positive for antibodies, evidence that they’d already been infected.

After this initial testing, all participants received antibody tests once every two months and diagnostic tests for an active COVID-19 infection at least every other week. What the researchers discovered was rather interesting. Eighty-nine of the 11,052 healthcare workers who tested negative at the outset later got a symptomatic COVID-19 infection. Another 76 individuals who originally tested negative for antibodies tested positive for COVID-19, despite having no symptoms.

Here’s the good news: Just three of these more than 1400 antibody-positive individuals subsequently tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. What’s more, not one of them had any symptoms of COVID-19.

The findings, which were posted as a pre-print on medRxiv, suggest that acquired immunity from an initial COVID-19 infection offers protection against reinfection for six months or maybe longer. Questions remain about whether the acquired immunity is due to the observed antibodies alone or their interplay with other immune cells. It will be important to continue to follow these healthcare workers even longer, to learn just how long their immune protection might last.

Meanwhile, more than 15 million people in the United States have now tested positive for COVID-19, leading to more than 285,000 deaths. Last week, the U.S. reported for the first time more than 200,000 new infections, with hospitalizations and deaths also on the rise.

While the new findings on reinfection come as good news to be sure, it’s important to remember that the vast majority of the 328 million Americans still remain susceptible to this life-threatening virus. So, throughout this holiday season and beyond—as we eagerly await the approval and widespread distribution of vaccines—we must all continue to do absolutely everything we can to protect ourselves, our loved ones, and our communities from COVID-19.

Reference:

[1] Antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 are associated with protection against reinfection. Lumley, S.F. et al. MedRxiv. 19 November 2020.

Links:

Coronavirus (COVID) (NIH)

Combat COVID (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Washington, D.C.)

David Eyre (University of Oxford, England)