inherited disease

DNA Base Editing May Treat Progeria, Study in Mice Shows

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

My good friend Sam Berns was born with a rare genetic condition that causes rapid premature aging. Though Sam passed away in his teens from complications of this condition, called Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome, he’s remembered today for his truly positive outlook on life. Sam expressed it, in part, by his willingness to make adjustments that allowed him, in his words, to put things that he always wanted to do in the “can do” category.

In this same spirit on behalf of the several hundred kids worldwide with progeria and their families, a research collaboration, including my NIH lab, has now achieved a key technical advance to move non-heritable gene editing another step closer to the “can do” category to treat progeria. As published in the journal Nature, our team took advantage of new gene-editing tools to correct for the first time a single genetic misspelling responsible for progeria in a mouse model, with dramatically beneficial effects [1, 2]. This work also has implications for correcting similar single-base typos that cause other inherited genetic disorders.

The outcome of this work is incredibly gratifying for me. In 2003, my NIH lab discovered the DNA mutation that causes progeria. One seemingly small glitch—swapping a “T” in place of a “C” in a gene called lamin A (LMNA)—leads to the production of a toxic protein now known as progerin. Without treatment, children with progeria develop normally intellectually but age at an exceedingly rapid pace, usually dying prematurely from heart attacks or strokes in their early teens.

The discovery raised the possibility that correcting this single-letter typo might one day help or even cure children with progeria. But back then, we lacked the needed tools to edit DNA safely and precisely. To be honest, I didn’t think that would be possible in my lifetime. Now, thanks to advances in basic genomic research, including work that led to the 2020 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, that’s changed. In fact, there’s been substantial progress toward using gene-editing technologies, such as the CRISPR editing system, for treating or even curing a wide range of devastating genetic conditions, such as sickle cell disease and muscular dystrophy

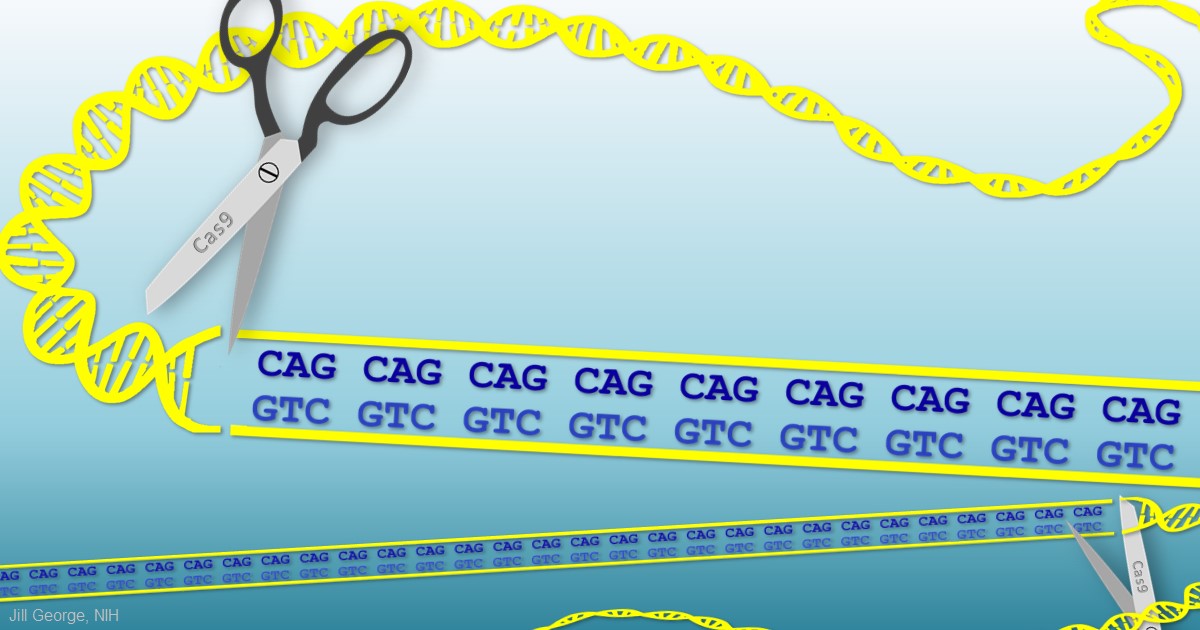

It turns out that the original CRISPR system, as powerful as it is, works better at knocking out genes than correcting them. That’s what makes some more recently developed DNA editing agents and approaches so important. One of them, which was developed by David R. Liu, Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, MA, and his lab members, is key to these latest findings on progeria, reported by a team including my lab in NIH’s National Human Genome Research Institute and Jonathan Brown, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN.

The relatively new gene-editing system moves beyond knock-outs to knock-ins [3,4]. Here’s how it works: Instead of cutting DNA as CRISPR does, base editors directly convert one DNA letter to another by enzymatically changing one DNA base to become a different base. The result is much like the find-and-replace function used to fix a typo in a word processor. What’s more, the gene editor does this without cutting the DNA.

Our three labs (Liu, Brown, and Collins) first teamed up with the Progeria Research Foundation, Peabody, MA, to obtain skin cells from kids with progeria. In lab studies, we found that base editors, targeted by an appropriate RNA guide, could successfully correct the LMNA gene in those connective tissue cells. The treatment converted the mutation back to the normal gene sequence in an impressive 90 percent of the cells.

But would it work in a living animal? To get the answer, we delivered a single injection of the DNA-editing apparatus into nearly a dozen mice either three or 14 days after birth, which corresponds in maturation level roughly to a 1-year-old or 5-year-old human. To ensure the findings in mice would be as relevant as possible to a future treatment for use in humans, we took advantage of a mouse model of progeria developed in my NIH lab in which the mice carry two copies of the human LMNA gene variant that causes the condition. Those mice develop nearly all of the features of the human illness

In the live mice, the base-editing treatment successfully edited in the gene’s healthy DNA sequence in 20 to 60 percent of cells across many organs. Many cell types maintained the corrected DNA sequence for at least six months—in fact, the most vulnerable cells in large arteries actually showed an almost 100 percent correction at 6 months, apparently because the corrected cells had compensated for the uncorrected cells that had died out. What’s more, the lifespan of the treated animals increased from seven to almost 18 months. In healthy mice, that’s approximately the beginning of old age.

This is the second notable advance in therapeutics for progeria in just three months. Last November, based on preclinical work from my lab and clinical trials conducted by the Progeria Research Foundation in Boston, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first treatment for the condition. It is a drug called Zokinvy, and works by reducing the accumulation of progerin [5]. With long-term treatment, the drug is capable of extending the life of kids with progeria by 2.5 years and sometimes more. But it is not a cure.

We are hopeful this gene editing work might eventually lead to a cure for progeria. But mice certainly aren’t humans, and there are still important steps that need to be completed before such a gene-editing treatment could be tried safely in people. In the meantime, base editors and other gene editing approaches keep getting better—with potential application to thousands of genetic diseases where we know the exact gene misspelling. As we look ahead to 2021, the dream envisioned all those years ago about fixing the tiny DNA typo responsible for progeria is now within our grasp and getting closer to landing in the “can do” category.

References:

[1] In vivo base editing rescues Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria Syndrome in mice. Koblan LW et al. Nature. 2021 Jan 6.

[2] Base editor repairs mutation found in the premature-ageing syndrome progeria. Vermeij WP, Hoeijmakers JHJ. Nature. 6 Jan 2021.

[3] Programmable editing of a target base in genomic DNA without double-stranded DNA cleavage. Komor AC, Kim YB, Packer MS, Zuris JA, Liu DR. Nature. 2016 May 19;533(7603):420-424.

[4] Programmable base editing of A•T to G•C in genomic DNA without DNA cleavage. Gaudelli NM, Komor AC, Rees HA, Packer MS, Badran AH, Bryson DI, Liu DR. Nature. 2017 Nov 23;551(7681):464-471.

[5] FDA approves first treatment for Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome and some progeroid laminopathies. Food and Drug Administration. 2020 Nov 20.

Links:

Progeria (Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center/NIH)

What are Genome Editing and CRISPR-Cas9? (National Library of Medicine/NIH)

Somatic Cell Genome Editing Program (Common Fund/NIH)

David R. Liu (Harvard University, Cambridge, MA)

Collins Group (National Human Genome Research Institute/NIH)

Jonathan Brown (Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN)

NIH Support: National Human Genome Research Institute; National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences; National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; National Institute of General Medical Sciences; Common Fund

Huntington’s Disease: Gene Editing Shows Promise in Mouse Studies

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

My father was a folk song collector, and I grew up listening to the music of Woody Guthrie. On July 14th, folk music enthusiasts will be celebrating the 105th anniversary of Guthrie’s birth in his hometown of Okemah, OK. Besides being renowned for writing “This Land is Your Land” and other folk classics, Guthrie has another more tragic claim to fame: he provided the world with a glimpse at the devastation caused by a rare, inherited neurological disorder called Huntington’s disease.

My father was a folk song collector, and I grew up listening to the music of Woody Guthrie. On July 14th, folk music enthusiasts will be celebrating the 105th anniversary of Guthrie’s birth in his hometown of Okemah, OK. Besides being renowned for writing “This Land is Your Land” and other folk classics, Guthrie has another more tragic claim to fame: he provided the world with a glimpse at the devastation caused by a rare, inherited neurological disorder called Huntington’s disease.

When Guthrie died from complications of Huntington’s a half-century ago, the disease was untreatable. Sadly, it still is. But years of basic science advances, combined with the promise of innovative gene editing systems such as CRISPR/Cas9, are providing renewed hope that we will someday be able to treat or even cure Huntington’s disease, along with many other inherited disorders.

Creative Minds: Can Diseased Cells Help to Make Their Own Drugs?

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Matthew Disney grew up in a large family in Baltimore in the 1980s. While his mother worked nights, Disney and his younger brother often tagged along with their father in these pre-Internet days on calls to fix the microfilm machines used to view important records at hospitals, banks, and other places of business. Watching his father take apart the machines made Disney want to work with his hands one day. Seeing his father work tirelessly for the sake of his family also made him want to help others.

Disney found a profession that satisfied both requirements when he fell in love with chemistry as an undergraduate at the University of Maryland, College Park. Now a chemistry professor at The Scripps Research Institute, Jupiter, FL, Disney is applying his hands and brains to develop a treatment strategy that aims to control the progression of a long list of devastating disorders that includes Huntington’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and various forms of muscular dystrophy.

The 30 or so health conditions on Disney’s list have something in common. They are caused by genetic glitches in which repetitive DNA letters (CAGCAGCAG, for example) in transcribed regions of the genome cause some of the body’s cells and tissues to produce unwieldy messenger RNA molecules that interfere with normal cellular activities, either by binding other intracellular components or serving as templates for the production of toxic proteins.

The diseases on Disney’s list also have often been considered “undruggable,” in part because the compounds capable of disabling the lengthy, disease-causing RNA molecules are generally too large to cross cell membranes. Disney has found an ingenious way around that problem [1]. Instead of delivering the finished drug, he delivers smaller building blocks. He then uses the cell and its own machinery, including the very aberrant RNA molecules he aims to target, as his drug factory to produce those larger compounds.

Disney has received an NIH Director’s 2015 Pioneer Award to develop this innovative drug-delivery strategy further. He will apply his investigational approach initially to treat a common form of muscular dystrophy, first using human cells in culture and then in animal models. Once he gets that working well, he’ll move on to other conditions including ALS.

What’s appealing about Disney’s approach is that it makes it possible to treat disease-affected cells without affecting healthy cells. That’s because his drugs can only be assembled into their active forms in cells after they are templated by those aberrant RNA molecules.

Interestingly, Disney never intended to study human diseases. His lab was set up to study the structure and function of RNA molecules and their interactions with other small molecules. In the process, he stumbled across a small molecule that targets an RNA implicated in a rare form of muscular dystrophy. His niece also has a rare incurable disease, and Disney saw a chance to make a difference for others like her. It’s a healthy reminder that the pursuit of basic scientific questions often can lead to new and unexpectedly important medical discoveries that have the potential to touch the lives of many.

Reference:

[1] A toxic RNA catalyzes the in cellulo synthesis of its own inhibitor. Rzuczek SG, Park H, Disney MD. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2014 Oct 6;53(41):10956-10959.

Links:

Disney Lab (The Scripps Research Institute, Jupiter, FL)

Disney NIH Project Information (NIH RePORTER)

NIH Director’s Pioneer Award Program

NIH Support: Common Fund; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke