IgG

How to Feed a Macrophage

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

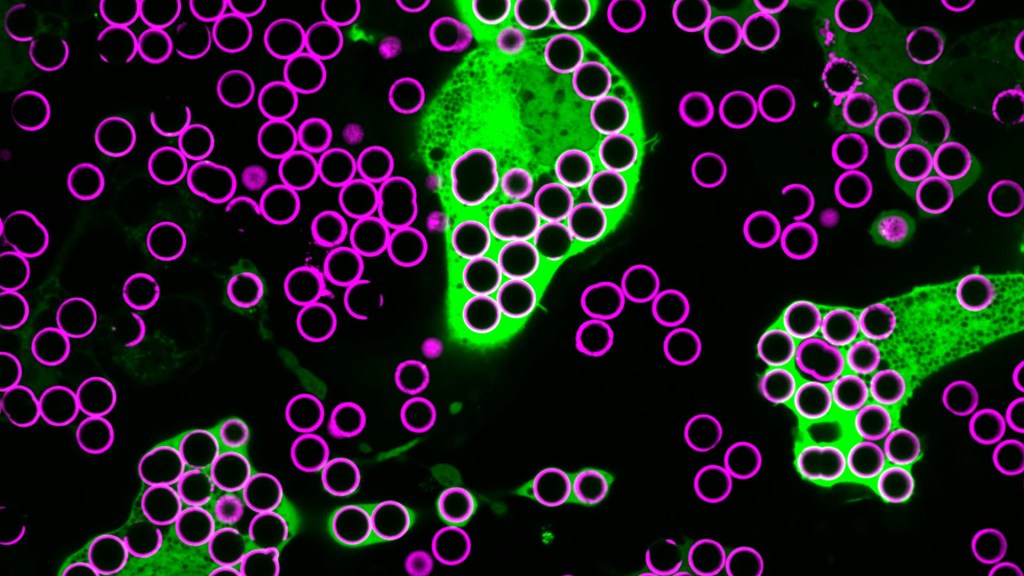

For Annalise Bond, a graduate student in the lab of Meghan Morrissey, University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB), macrophages are “the professional eaters of our immune system.” Every minute of every day, macrophages somewhere in the body are gorging themselves to remove the cellular debris that builds up in our tissues and organs.

In this image, Bond caught several macrophages (green) doing what they do best: shoveling it in—in this case, during a lab experiment. The macrophages are consuming silica beads (purple) prepared with biochemicals that whet their appetites. Each bead measures about five microns in diameter. That’s roughly the size of a bacterium or a spent red blood cell—debris that a macrophage routinely consumes.

When Bond snapped this image, she noticed a pattern that reminded her of a childhood tabletop game called Hungry Hungry Hippos. Kids press a lever attached to the mouth of a plastic hippo, its lower jaw flaps open, and the challenge is to fill the mouth with as many marbles as possible . . . just like the macrophages eating beads.

Bond adjusted the colors in the photo to make them pop. She then entered it into UCSB’s 2023 Art of Science contest with the caption of Hungry Hungry Macrophages, winning high marks for drawing the association.

Though the caption was written in fun, Bond studies in earnest a fascinating biological question: How do macrophages know what to eat in the body and what to leave untouched?

In her studies, Bond coats the silica beads shown above with a lipid bilayer to mimic a cell membrane. To that coating, she adds various small molecules and proteins as “eat-me” signals often found on the surface of dying cells. Some of the signals are well characterized; but many aren’t, meaning there’s still a lot to learn about what makes a macrophage “particularly hungry” and what makes a particular target cell “extra tasty.”

Capturing fluorescent images of macrophages under the microscope, Bond counts up how many beads are eaten. Beads bearing no signal to stimulate their appetite might get eaten occasionally. But when an especially enticing signal is added, macrophages will gorge themselves until they can’t eat anymore.

In the experiment pictured above, the beads contain the antibody immunoglobulin G (IgG), which tags foreign pathogens for macrophage removal. Interestingly, IgG antibody responses also play an important role in cancer immunotherapies, in which the immune system is unleashed to fight cancer.

Among its many areas of study, the NIH-supported Morrissey lab’s wants to understand better how macrophages interact with cancer cells. They want to learn how to make cancer cells even tastier to macrophages and program their elimination from the body. Sorting out the signals will be challenging, but we know that macrophages will take a bite at the right ones. They are, after all, professional eaters.

Links:

Cancer Immunotherapy (NIH)

Annalise Bond (University of California, Santa Barbara)

Morrissey Lab (University of California, Santa Barbara)

Art of Science (University of California, Santa Barbara)

NIH Support: National Institute of General Medical Sciences

Could a Nasal Spray of Designer Antibodies Help to Beat COVID-19?

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

There are now several monoclonal antibodies, identical copies of a therapeutic antibody produced in large numbers, that are authorized for the treatment of COVID-19. But in the ongoing effort to beat this terrible pandemic, there’s plenty of room for continued improvements in treating infections with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19.

With this in mind, I’m pleased to share progress in the development of a specially engineered therapeutic antibody that could be delivered through a nasal spray. Preclinical studies also suggest it may work even better than existing antibody treatments to fight COVID-19, especially now that new SARS-CoV-2 “variants of concern” have become increasingly prevalent.

These findings come from Zhiqiang An, The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, and Pei-Yong Shi, The University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston, and their colleagues. The NIH-supported team recognized that the monoclonal antibodies currently in use all require time-consuming, intravenous infusion at high doses, which has limited their use. Furthermore, because they are delivered through the bloodstream, they aren’t able to reach directly the primary sites of viral infection in the nasal passages and lungs. With the emergence of new SARS-CoV-2 variants, there’s also growing evidence that some of those therapeutic antibodies are becoming less effective in targeting the virus.

Antibodies come in different types. Immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies, for example, are most prevalent in the blood and have the potential to confer sustained immunity. Immunoglobulin A (IgA) antibodies are found in tears, mucus, and other bodily secretions where they protect the body’s moist, inner linings, or mucosal surfaces, of the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts. Immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibodies are also important for protecting mucosal surfaces and are produced first when fighting an infection.

Though IgA and IgM antibodies differ structurally, both can be administered in an inhaled mist. However, monoclonal antibodies now used to treat COVID-19 are of the IgG type, which must be IV infused.

In the new study, the researchers stitched IgG fragments known for their ability to target SARS-CoV-2 together with those rapidly responding IgM antibodies. They found that this engineered IgM antibody, which they call IgM-14, is more than 230 times better than the IgG antibody that they started with in neutralizing SARS-CoV-2.

Importantly, IgM-14 also does a good job of neutralizing SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern. These include the B.1.1.7 “U.K.” variant (now also called Alpha), the P.1 “Brazilian” variant (called Gamma), and the B.1.351 “South African” variant (called Beta). It also works against 21 other variants carrying alterations in the receptor binding domain (RBD) of the virus’ all-important spike protein. This protein, which allows SARS-CoV-2 to infect human cells, is a prime target for antibodies. Many of these alterations are expected to make the virus more resistant to monoclonal IgG antibodies that are now authorized by the FDA for emergency use.

But would it work to protect against coronavirus infection in a living animal? To find out, the researchers tried it in mice. They squirted a single dose of the IgM-14 antibody into the noses of mice either six hours before exposure to SARS-CoV-2 or six hours after infection with either the P.1 or B.1.351 variants.

In all cases, the antibody delivered in this way worked two days later to reduce dramatically the amount of SARS-CoV-2 in the lungs. That’s important because the amount of virus in the respiratory tracts of infected people is closely linked to severe illness and death due to COVID-19. If the new therapeutic antibody is proven safe and effective in people, it suggests it could become an important tool for reducing the severity of COVID-19, or perhaps even preventing infection altogether.

The researchers already have licensed this new antibody to a biotechnology partner called IGM Biosciences, Mountain View, CA, for further development and future testing in a clinical trial. If all goes well, the hope is that we’ll have a safe and effective nasal spray to serve as an extra line of defense in the fight against COVID-19.

Reference:

[1] Nasal delivery of an IgM offers broad protection from SARS-CoV-2 variants. Ku Z, Xie X, Hinton PR, Liu X, Ye X, Muruato AE, Ng DC, Biswas S, Zou J, Liu Y, Pandya D, Menachery VD, Rahman S, Cao YA, Deng H, Xiong W, Carlin KB, Liu J, Su H, Haanes EJ, Keyt BA, Zhang N, Carroll SF, Shi PY, An Z. Nature. 2021 Jun 3.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Zhiqiang An (The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston)

Pei-Yong Shi (The University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston)

IGM Biosciences (Mountain View, CA)

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences; National Cancer Institute

Antibody Response Affects COVID-19 Outcomes in Kids and Adults

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Doctors can’t reliably predict whether an adult newly diagnosed with COVID-19 will recover quickly or battle life-threatening complications. The same is true for children.

Thankfully, the vast majority of kids with COVID-19 don’t get sick or show only mild flu-like symptoms. But a small percentage develop a delayed, but extremely troubling, syndrome called multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C). This can cause severe inflammation of the heart, lungs, kidneys, brain, and other parts of the body, coming on weeks after recovering from COVID-19. Fortunately, most kids respond to treatment and make rapid recoveries.

COVID-19’s sometimes different effects on kids likely stem not from the severity of the infection itself, but from differences in the immune response or its aftermath. Additional support for this notion comes from a new study, published in the journal Nature Medicine, that compared immune responses among children and adults with COVID-19 [1]. The study shows that the antibody responses in kids and adults with mild COVID-19 are quite similar. However, the complications seen in kids with MIS-C and adults with severe COVID-19 appear to be driven by two distinctly different types of antibodies involved in different aspects of the immune response.

The new findings come from pediatric pulmonologist Lael Yonker, Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Cystic Fibrosis Center, Boston, and immunologist Galit Alter, the Ragon Institute of MGH, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and Harvard, Cambridge. Yonker runs a biorepository that collects samples from kids with cystic fibrosis. When the pandemic began, she started collecting plasma samples from children with mild COVID-19. Then, when Yonker and others began to see children hospitalized with MIS-C, she collected some plasma samples from them, too.

Using these plasma samples as windows into a child’s immune response, the research teams of Yonker and Alter detailed antibodies generated in 17 kids with MIS-C and 25 kids with mild COVID-19. They also profiled antibody responses of 60 adults with COVID-19, including 26 with severe disease.

Comparing antibody profiles among the four different groups, the researchers had expected children’s antibody responses to look quite different from those in adults. But they were in for a surprise. Adults and kids with mild COVID-19 showed no notable differences in their antibody profiles. The differences only came into focus when they compared antibodies in kids with MIS-C to adults with severe COVID-19.

In kids who develop MIS-C after COVID-19, they saw high levels of long-lasting immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies, which normally help to control an acute infection. Those high levels of IgG antibodies weren’t seen in adults or in kids with mild COVID-19. The findings suggest that in kids with MIS-C, those antibodies may activate scavenging immune cells, called macrophages, to drive inflammation and more severe illness.

In adults with severe COVID-19, the pattern differed. Instead of high levels of IgG antibodies, adults showed increased levels of another type of antibody, called immunoglobulin A (IgA). These IgA antibodies apparently were interacting with immune cells called neutrophils, which in turn led to the release of cytokines. That’s notable because the release of too many cytokines can cause what’s known as a “cytokine storm,” a severe symptom of COVID-19 that’s associated with respiratory distress syndrome, multiple organ failure, and other life-threatening complications.

To understand how a single virus can cause such different outcomes, studies like this one help to tease out their underlying immune mechanisms. While more study is needed to understand the immune response over time in both kids and adults, the hope is that these findings and others will help put us on the right path to discover better ways to help protect people of all ages from the most severe complications of COVID-19.

Reference:

[1] Humoral signatures of protective and pathological SARS-CoV-2 infection in children. Bartsch YC, Wang C, Zohar T, Fischinger S, Atyeo C, Burke JS, Kang J, Edlow AG, Fasano A, Baden LR, Nilles EJ, Woolley AE, Karlson EW, Hopke AR, Irimia D, Fischer ES, Ryan ET, Charles RC, Julg BD, Lauffenburger DA, Yonker LM, Alter G. Nat Med. 2021 Feb 12.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

“NIH effort seeks to understand MIS-C, range of SARS-CoV-2 effects on children,” NIH news release, March 2, 2021.

Lael Yonker (Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston)

Alter Lab (Ragon Institute of Massachusetts General Hospital, MIT, and Harvard, Cambridge)

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; National Cancer Institute

Two Studies Show COVID-19 Antibodies Persist for Months

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

More than 8 million people in the United States have now tested positive for COVID-19. For those who’ve recovered, many wonder if fending off SARS-CoV-2—the coronavirus that causes COVID-19—one time means their immune systems will protect them from reinfection. And, if so, how long will this “acquired immunity” last?

The early data brought hope that acquired immunity was possible. But some subsequent studies have suggested that immune protection might be short-lived. Though more research is needed, the results of two recent studies, published in the journal Science Immunology, support the early data and provide greater insight into the nature of the human immune response to this coronavirus [1,2].

The new findings show that people who survive a COVID-19 infection continue to produce protective antibodies against key parts of the virus for at least three to four months after developing their first symptoms. In contrast, some other antibody types decline more quickly. The findings offer hope that people infected with the virus will have some lasting antibody protection against re-infection, though for how long still remains to be determined.

In one of the two studies, partly funded by NIH, researchers led by Richelle Charles, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, sought a more detailed understanding of antibody responses following infection with SARS-CoV-2. To get a closer look, they enrolled 343 patients, most of whom had severe COVID-19 requiring hospitalization. They examined their antibody responses for up to 122 days after symptoms developed and compared them to antibodies in more than 1,500 blood samples collected before the pandemic began.

The researchers characterized the development of three types of antibodies in the blood samples. The first type was immunoglobulin G (IgG), which has the potential to confer sustained immunity. The second type was immunoglobulin A (IgA), which protects against infection on the body’s mucosal surfaces, such as those found in the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts, and are found in high levels in tears, mucus, and other bodily secretions. The third type is immunoglobulin M (IgM), which the body produces first when fighting an infection.

They found that all three types were present by about 12 days after infection. IgA and IgM antibodies were short-lived against the spike protein that crowns SARS-CoV-2, vanishing within about two months.

The good news is that the longer-lasting IgG antibodies persisted in these same patients for up to four months, which is as long as the researchers were able to look. Levels of those IgG antibodies also served as an indicator for the presence of protective antibodies capable of neutralizing SARS-CoV-2 in the lab. Even better, that ability didn’t decline in the 75 days after the onset of symptoms. While longer-term study is needed, the findings lend support to evidence that protective antibody responses against the novel virus do persist.

The other study came to very similar conclusions. The team, led by Jennifer Gommerman and Anne-Claude Gingras, University of Toronto, Canada, profiled the same three types of antibody responses against the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, They created the profiles using both blood and saliva taken from 439 people, not all of whom required hospitalization, who had developed COVID-19 symptoms from 3 to 115 days prior. The team then compared antibody profiles of the COVID-19 patients to those of people negative for COVID-19.

The researchers found that the antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 were readily detected in blood and saliva. IgG levels peaked about two weeks to one month after infection, and then remained stable for more than three months. Similar to the Boston team, the Canadian group saw IgA and IgM antibody levels drop rapidly.

The findings suggest that antibody tests can serve as an important tool for tracking the spread of SARS-CoV-2 through our communities. Unlike tests for the virus itself, antibody tests provide a means to detect infections that occurred sometime in the past, including those that may have been asymptomatic. The findings from the Canadian team further suggest that tests of IgG antibodies in saliva may be a convenient way to track a person’s acquired immunity to COVID-19.

Because IgA and IgM antibodies decline more quickly, testing for these different antibody types also could help to distinguish between an infection within the last two months and one that more likely occurred even earlier. Such details are important for filling in gaps in our understanding COVID-19 infections and tracking their spread in our communities.

Still, there are rare reports of individuals who survived one bout with COVID-19 and were infected with a different SARS-CoV-2 strain a few weeks later [3]. The infrequency of such reports, however, suggests that acquired immunity after SARS-CoV-2 infection is generally protective.

There remain many open questions, and answering them will require conducting larger studies with greater diversity of COVID-19 survivors. So, I’m pleased to note that the NIH’s National Cancer Institute (NCI) recently launched the NCI Serological Sciences Network for COVID19 (SeroNet), now the nation’s largest coordinated effort to characterize the immune response to COVID-19 [4].

The network was established using funds from an emergency Congressional appropriation of more than $300 million to develop, validate, improve, and implement antibody testing for COVID-19 and related technologies. With help from this network and ongoing research around the world, a clearer picture will emerge of acquired immunity that will help to control future outbreaks of COVID-19.

References:

[1] Persistence and decay of human antibody responses to the receptor binding domain of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein in COVID-19 patients. Iyer AS, Jones FK, Nodoushani A, Ryan ET, Harris JB, Charles RC, et al. Sci Immunol. 2020 Oct 8;5(52):eabe0367.

[2] Persistence of serum and saliva antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 spike antigens in COVID-19 patients. Isho B, Abe KT, Zuo M, Durocher Y, McGeer AJ, Gommerman JL, Gingras AC, et al. Sci Immunol. 2020 Oct 8;5(52):eabe5511.

[3] What reinfections mean for COVID-19. Iwasaki A. Lancet Infect Dis, 2020 October 12. [Epub ahead of print]

[4] NIH to launch the Serological Sciences Network for COVID-19, announce grant and contract awardees. National Institutes of Health. 2020 October 8.

Links:

Coronavirus (COVID-19) (NIH)

Charles Lab (Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston)

Gingras Lab (University of Toronto, Canada)

Jennifer Gommerman (University of Toronto, Canada)

NCI Serological Sciences Network for COVID-19 (SeroNet) (National Cancer Institute/NIH)

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; National Institute of General Medical Sciences; National Cancer Institute

Study Finds Nearly Everyone Who Recovers From COVID-19 Makes Coronavirus Antibodies

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

There’s been a lot of excitement about the potential of antibody-based blood tests, also known as serology tests, to help contain the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. There’s also an awareness that more research is needed to determine when—or even if—people infected with SARS-CoV-2, the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19, produce antibodies that may protect them from re-infection.

A recent study in Nature Medicine brings much-needed clarity, along with renewed enthusiasm, to efforts to develop and implement widescale antibody testing for SARS-CoV-2 [1]. Antibodies are blood proteins produced by the immune system to fight foreign invaders like viruses, and may help to ward off future attacks by those same invaders.

In their study of blood drawn from 285 people hospitalized with severe COVID-19, researchers in China, led by Ai-Long Huang, Chongqing Medical University, found that all had developed SARS-CoV-2 specific antibodies within two to three weeks of their first symptoms. Although more follow-up work is needed to determine just how protective these antibodies are and for how long, these findings suggest that the immune systems of people who survive COVID-19 have been be primed to recognize SARS-CoV-2 and possibly thwart a second infection.

Specifically, the researchers determined that nearly all of the 285 patients studied produced a type of antibody called IgM, which is the first antibody that the body makes when fighting an infection. Though only about 40 percent produced IgM in the first week after onset of COVID-19, that number increased steadily to almost 95 percent two weeks later. All of these patients also produced a type of antibody called IgG. While IgG often appears a little later after acute infection, it has the potential to confer sustained immunity.

To confirm their results, the researchers turned to another group of 69 people diagnosed with COVID-19. The researchers collected blood samples from each person upon admission to the hospital and every three days thereafter until discharge. The team found that, with the exception of one woman and her daughter, the patients produced specific antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 within 20 days of their first symptoms of COVID-19.

Meanwhile, innovative efforts are being made on the federal level to advance COVID-19 testing. The NIH just launched the Rapid Acceleration of Diagnostics (RADx) Initiative to support a variety of research activities aimed at improving detection of the virus. As I recently highlighted on this blog, one key component of RADx is a “shark tank”-like competition to encourage science and engineering’s most inventive minds to develop rapid, easy-to-use technologies to test for the presence of SARS-CoV-2.

On the serology testing side, the NIH’s National Cancer Institute has been checking out kits that are designed to detect antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 and have found mixed results. In response, the Food and Drug Administration just issued its updated policy on antibody tests for COVID-19. This guidance sets forth precise standards for laboratories and commercial manufacturers that will help to speed the availability of high-quality antibody tests, which in turn will expand the capacity for rapid and widespread testing in the United States.

Finally, it’s important to keep in mind that there are two different types of SARS-CoV-2 tests. Those that test for the presence of viral nucleic acid or protein are used to identify people who are acutely infected and should be immediately quarantined. Tests for IgM and/or IgG antibodies to the virus, if well-validated, indicate a person has previously been infected with COVID-19 and is now potentially immune. Two very different types of tests—two very different meanings.

There’s still a way to go with both virus and antibody testing for COVID-19. But as this study and others begin to piece together the complex puzzle of antibody-mediated immunity, it will be possible to learn more about the human body’s response to SARS-CoV-2 and home in on our goal of achieving safe, effective, and sustained protection against this devastating disease.

Reference:

[1] Antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in patients with COVID-19. Long QX, Huang AI, et al. Nat Med. 2020 Apr 29. [Epub ahead of print]

Links:

Coronaviruses (NIH)

“NIH Begins Study to Quantify Undetected Cases of Coronavirus Infection,” NIH News Release, April 10, 2020.

“NIH mobilizes national innovation initiative for COVID-19 diagnostics,” NIH News Release, April 29, 2020.

Policy for Coronavirus Disease-2019 Tests During the Public Health Emergency (Revised), May 2020 (Food and Drug Administration)