UCSB 2023 Art of Science

How to Feed a Macrophage

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

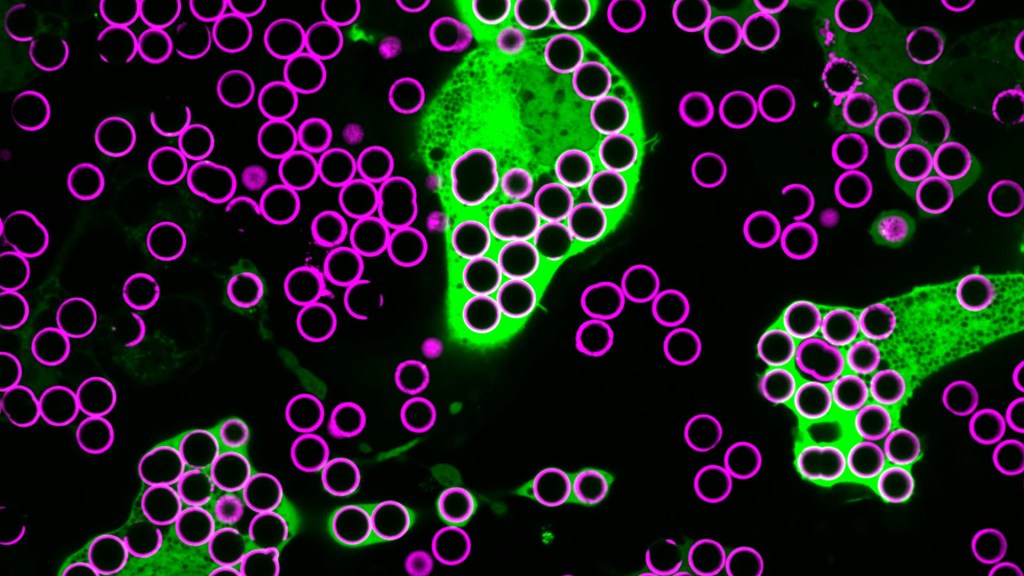

For Annalise Bond, a graduate student in the lab of Meghan Morrissey, University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB), macrophages are “the professional eaters of our immune system.” Every minute of every day, macrophages somewhere in the body are gorging themselves to remove the cellular debris that builds up in our tissues and organs.

In this image, Bond caught several macrophages (green) doing what they do best: shoveling it in—in this case, during a lab experiment. The macrophages are consuming silica beads (purple) prepared with biochemicals that whet their appetites. Each bead measures about five microns in diameter. That’s roughly the size of a bacterium or a spent red blood cell—debris that a macrophage routinely consumes.

When Bond snapped this image, she noticed a pattern that reminded her of a childhood tabletop game called Hungry Hungry Hippos. Kids press a lever attached to the mouth of a plastic hippo, its lower jaw flaps open, and the challenge is to fill the mouth with as many marbles as possible . . . just like the macrophages eating beads.

Bond adjusted the colors in the photo to make them pop. She then entered it into UCSB’s 2023 Art of Science contest with the caption of Hungry Hungry Macrophages, winning high marks for drawing the association.

Though the caption was written in fun, Bond studies in earnest a fascinating biological question: How do macrophages know what to eat in the body and what to leave untouched?

In her studies, Bond coats the silica beads shown above with a lipid bilayer to mimic a cell membrane. To that coating, she adds various small molecules and proteins as “eat-me” signals often found on the surface of dying cells. Some of the signals are well characterized; but many aren’t, meaning there’s still a lot to learn about what makes a macrophage “particularly hungry” and what makes a particular target cell “extra tasty.”

Capturing fluorescent images of macrophages under the microscope, Bond counts up how many beads are eaten. Beads bearing no signal to stimulate their appetite might get eaten occasionally. But when an especially enticing signal is added, macrophages will gorge themselves until they can’t eat anymore.

In the experiment pictured above, the beads contain the antibody immunoglobulin G (IgG), which tags foreign pathogens for macrophage removal. Interestingly, IgG antibody responses also play an important role in cancer immunotherapies, in which the immune system is unleashed to fight cancer.

Among its many areas of study, the NIH-supported Morrissey lab’s wants to understand better how macrophages interact with cancer cells. They want to learn how to make cancer cells even tastier to macrophages and program their elimination from the body. Sorting out the signals will be challenging, but we know that macrophages will take a bite at the right ones. They are, after all, professional eaters.

Links:

Cancer Immunotherapy (NIH)

Annalise Bond (University of California, Santa Barbara)

Morrissey Lab (University of California, Santa Barbara)

Art of Science (University of California, Santa Barbara)

NIH Support: National Institute of General Medical Sciences