Southeast Asia

Battling Malaria at the Atomic Level

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Tropical medicine has its share of wily microbes. Among the most clever is the mosquito-borne protozoan Plasmodium falciparum, which is the cause of the most common—and most lethal—form of malaria. For decades, doctors have used antimalarial drugs against P. falciparum. But just when malaria appeared to be well on its way to eradication, this parasitic protozoan mutated in ways that has enabled it to resist frontline antimalarial drugs. This resistance is a major reason that malaria, one of the world’s oldest diseases, still claims the lives of about 400,000 people each year [1].

This is a situation with which I have personal experience. Thirty years ago before traveling to Nigeria, I followed directions and took chloroquine to prevent malaria. But the resistance to the drug was already widespread, and I came down with malaria anyway. Fortunately, the parasite that a mosquito delivered to me was sensitive to another drug called Fansidar, which acts through another mechanism. I was pretty sick for a few days, but recovered without lasting consequences.

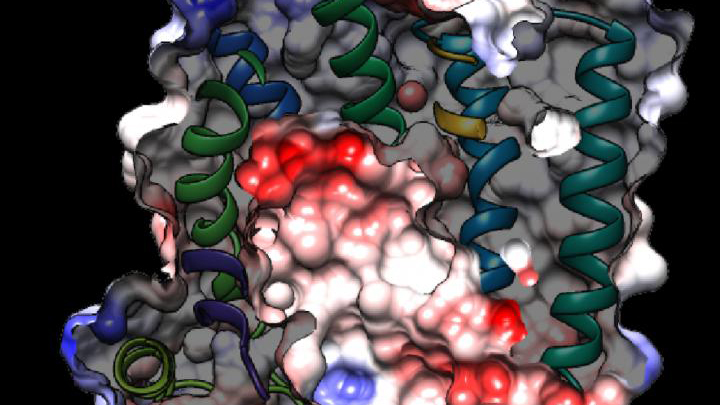

While new drugs are being developed to thwart P. falciparum, some researchers are busy developing tools to predict what mutations are likely to occur next in the parasite’s genome. And that’s what is so exciting about the image above. It presents the unprecedented, 3D atomic-resolution structure of a protein made by P. falciparum that’s been a major source of its resistance: the chloroquine-resistance transporter protein, or PfCRT.

In this cropped density map, you see part of the protein’s biochemical structure. The colorized area displays the long, winding chain of amino acids within the protein as helices in shades of green, blue and gold. These helices enclose a central cavity essential for the function of the protein, whose electrostatic properties are shown here as negative (red), positive (blue), and neutral (white). All this structural information was captured using cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM). The technique involves flash-freezing molecules in liquid nitrogen and bombarding them with electrons to capture their images with a special camera.

This groundbreaking work, published recently in Nature, comes from an NIH-supported multidisciplinary research team, led by David Fidock, Matthias Quick, and Filippo Mancia, Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York [2]. It marks a major feat for structural biology, because PfCRT is on the small side for standard cryo-EM and, as Mancia discovered, the protein is almost featureless.

These two strikes made Mancia and colleagues wonder at first whether they would swing and miss at their attempt to image the protein. With the help of coauthor Anthony Kossiakoff, a researcher at the University of Chicago, the team complexed PfCRT to a bulkier antibody fragment. That doubled the size of their subject, and the fragment helped to draw out PfCRT’s hidden features. One year and a lot of hard work later, they got their homerun.

PfCRT is a transport protein embedded in the surface membrane of what passes for the gut of P. falciparum. Because the gene encoding it is highly mutable, the PfCRT protein modified its structure many years ago, enabling it to pump out and render ineffective several drugs in a major class of antimalarials called 4-aminoquinolines. That includes chloroquine.

Now, with the atomic structure in hand, researchers can map the locations of existing mutations and study how they work. This information will also allow them to model which regions of the protein to be on the lookout for the next adaptive mutations. The hope is this work will help to prolong the effectiveness of today’s antimalarial drugs.

For example, the drug piperaquine, a 4-aminoquinoline agent, is now used in combination with another antimalarial. The combination has proved quite effective. But recent reports show that P. falciparum has acquired resistance to piperaquine, driven by mutations in PfCRT that are spreading rapidly across Southeast Asia [3].

Interestingly, the researchers say they have already pinpointed single mutations that could confer piperaquine resistance to parasites from South America. They’ve also located where new mutations are likely to occur to compromise the drug’s action in Africa, where most malarial infections and deaths occur. So, this atomic structure is already being put to good use.

Researchers also hope that this model will allow drug designers to make structural adjustments to old, less effective malarial drugs and perhaps restore them to their former potency. Perhaps this could even be done by modifying chloroquine, introduced in the 1940s as the first effective antimalarial. It was used worldwide but was largely shelved a few decades later due to resistance—as I experienced three decades ago.

Malaria remains a constant health threat for millions of people living in subtropical areas of the world. Wouldn’t it be great to restore chloroquine to the status of a frontline antimalarial? The drug is inexpensive, taken orally, and safe. Through the power of science, its return is no longer out of the question.

References:

[1] World malaria report 2019. World Health Organization, December 4, 2019

[2] Structure and drug resistance of the Plasmodium falciparum transporter PfCRT. Kim J, Tan YZ, Wicht KJ, Erramilli SK, Dhingra SK, Okombo J, Vendome J, Hagenah LM, Giacometti SI, Warren AL, Nosol K, Roepe PD, Potter CS, Carragher B, Kossiakoff AA, Quick M, Fidock DA, Mancia F. Nature. 2019 Dec;576(7786):315-320.

[3] Determinants of dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine treatment failure in Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Cambodia, Thailand, and Vietnam: a prospective clinical, pharmacological, and genetic study. van der Pluijm RW, Imwong M, Chau NH, Hoa NT, et. al. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019 Sep;19(9):952-961.

Links:

Malaria (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases/NIH)

Fidock Lab (Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York)

Video: David Fidock on antimalarial drug resistance (BioMedCentral/YouTube)

Kossiakoff Lab (University of Chicago)

Mancia Lab (Columbia University Irving Medical Center)

Matthias Quick (Columbia University Irving Medical Center)

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; National Institute of General Medical Sciences; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

Climate and Viral Illness: El Niño Event Linked to Dengue Epidemics

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Just as the severity of the winter flu fluctuates from year to year in the United States, dengue fever can rage through tropical and subtropical regions of the world during their annual rainy seasons, causing potentially life-threatening high fever, severe joint pain, and bleeding. Other years—for still unknown reasons—dengue fizzles out. While many nations monitor the incidence of dengue within their borders, their data aren’t always combined to track outbreaks across wider regions over longer times.

Now, NIH-funded researchers and colleagues, reporting in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences [1], have linked an intense dengue epidemic that struck eight Southeast Asian countries starting in mid-1997 to high temperatures driven by the strongest El Niño event in recent times. El Niño is a complex, irregularly occurring series of climate changes in the Pacific Ocean with a global impact on weather patterns. This new insight into climatic factors associated with dengue transmission could enable better prevention measures, which may soon be needed because climatologists are predicting another strong El Niño event next year due to unusually high ocean temperatures in the equatorial Pacific.