ovarian cancer

Encouraging News for Kids with Neurofibromatosis Type 1

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Amid all the headlines and uncertainty surrounding the current COVID-19 pandemic, it’s easy to overlook the important progress that biomedical research is making against other diseases. So, today, I’m pleased to share word of what promises to be the first effective treatment to help young people suffering from the consequences of a painful, often debilitating genetic disorder called neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1).

This news is particularly meaningful to me because, 30 years ago, I led a team that discovered the gene that underlies NF1. About 1 in 3,000 babies are born with NF1. In about half of those affected, a type of tumor called a plexiform neurofibroma arises along nerves in the skin, face, and other parts of the body. While plexiform neurofibromas are not cancerous, they grow steadily and can lead to severe pain and a range of other health problems, including vision and hearing loss, hypertension, and mobility issues.

The good news is the results of a phase II clinical trial involving NF1, just published in the New England Journal of Medicine. The trial was led by Brigitte Widemann and Andrea Gross, researchers in the Center for Cancer Research at NIH’s National Cancer Institute.

The trial’s results confirm that a drug originally developed to treat cancer, called selumetinib, can shrink inoperable tumors in many children with NF1. They also establish that the drug can help affected kids make significant improvements in strength, range of motion, and quality of life. While selumetinib is not a cure, and further studies are still needed to see how well the treatment works in the long term, these results suggest that the first effective treatment for NF1 is at last within our reach.

Selumetinib blocks a protein in human cells called MEK. This protein is involved in a major cellular pathway known as RAS that can become dysregulated and give rise to various cancers. By blocking the MEK protein in animal studies and putting the brakes on the RAS pathway when it malfunctions, selumetinib showed great initial promise as a cancer drug.

Selumetinib was first tested several years ago in people with a variety of other cancers, including ovarian and non-small cell lung cancers. The clinical research looked good at first but eventually stalled, and so did much of the initial enthusiasm for selumetinib.

But the enthusiasm picked up when researchers considered repurposing the drug to treat NF1. The neurofibromas associated with the condition were known to arise from a RAS-activating loss of the NF1 gene. It made sense that blocking the MEK protein might blunt the overactive RAS signal and help to shrink these often-inoperable tumors.

An earlier phase 1 safety trial looked promising, showing for the first time that the drug could, in some cases, shrink large NF1 tumors [2]. This fueled further research, and the latest study now adds significantly to that evidence.

In the study, Widemann and colleagues enrolled 50 children with NF1, ranging in age from 3 to 17. Their tumor-related symptoms greatly affected their wellbeing and ability to thrive, including disfigurement, limited strength and motion, and pain. Children received selumetinib alone orally twice a day and went in for assessments at least every four months.

As of March 2019, 35 of the 50 children in the ongoing study had a confirmed partial response, meaning that their tumors had shrunk by more than 20 percent. Most had maintained that response for a year or more. More importantly, the kids also felt less pain and were more able to enjoy life.

It’s important to note that the treatment didn’t work for everyone. Five children stopped taking the drug due to side effects. Six others progressed while on the drug, though five of them had to reduce their dose because of side effects before progressing. Nevertheless, for kids with NF1 and their families, this is a big step forward.

Drug developer AstraZeneca, working together with the researchers, has submitted a New Drug Application to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). While they’re eagerly awaiting the FDA’s decision, the work continues.

The researchers want to learn much more about how the drug affects the health and wellbeing of kids who take it over the long term. They’re also curious whether it could help to prevent the growth of large tumors in kids who begin taking it earlier in the course of the disease, and whether it might benefit other features of the disorder. They will continue to look ahead to other potentially promising treatments or treatment combinations that may further help, and perhaps one day even cure, kids with NF1. So, even while we cope with the COVID-19 pandemic, there are reasons to feel encouraged and grateful for continued progress made throughout biomedical research.

References:

[1] Selumitinib in children with inoperable plexiform neurofibromas. New England Journal of Medicine. Gross AM, Wolters PL, Dombi E, Baldwin A, Whitcomb P, Fisher MJ, Weiss B, Kim A, Bornhorst M, Shah AC, Martin S, Roderick MC, Pichard DC, Carbonell A, Paul SM, Therrien J, Kapustina O, Heisey K, Clapp DW, Zhang C, Peer CJ, Figg WD, Smith M, Glod J, Blakeley JO, Steinberg SM, Venzon DJ, Doyle LA, Widemann BC. 18 March 2020. N Engl J Med. 2020 Mar 18. [Epub ahead of publication.]

[2] Activity of selumetinib in neurofibromatosis type 1-related plexiform neurofibromas. Dombi E, Baldwin A, Marcus LJ, Fisher MJ, Weiss B, Kim A, Whitcomb P, Martin S, Aschbacher-Smith LE, Rizvi TA, Wu J, Ershler R, Wolters P1, Therrien J, Glod J, Belasco JB, Schorry E, Brofferio A, Starosta AJ, Gillespie A, Doyle AL, Ratner N, Widemann BC. N Engl J Med. 2016 Dec 29;375(26):2550-2560.

Links:

Neurofibromatosis Fact Sheet (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke/NIH)

Brigitte Widemann (National Cancer Institute/NIH)

Andrea Gross (National Cancer Institute/NIH)

NIH Support: National Cancer Institute

Detecting Cancer with a Herringbone Nanochip

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: Yong Zeng, University of Kansas, Lawrence and Kansas City

The herringbone motif is familiar as the classic, V-shaped patterned weave long popular in tweed jackets. But the nano-sized herringbone pattern seen here is much more than a fashion statement. It helps to solve a tricky design problem for a cancer-detecting “lab-on-a-chip” device.

A research team, led by Yong Zeng, University of Kansas, Lawrence, and Andrew Godwin at the University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City. previously developed a lab-on-a-chip that senses exosomes. They are tiny bubble-shaped structures that most mammalian cells secrete constantly into the bloodstream [1]. Once thought of primarily as trash bags used by cells to rid themselves of waste products, exosomes carry important molecular information (RNA, protein, and metabolites) used by cells to communicate and influence the behavior of other cells.

What’s also interesting, tumor cells produce more exosomes than healthy cells. That makes these 30-to-150-nanometer structures (a nanometer is a billionth of a meter) potentially useful for detecting cancer. In fact, these NIH-funded researchers found that their microfluidic device can detect exosomes from ovarian cancer within a 2-microliter blood sample. That’s just 1/25th of a drop!

But there was a technical challenge. When such tiny samples are placed into microfluidic channels, the fluid and any particles within it tend to flow in parallel layers without any mixing between them. As a result, exosomes can easily pass through undetected, without ever touching the biosensors on the surface of the chip.

That’s where the herringbone comes in. As reported in Nature Biomedical Engineering, when fluid flows over those 3D herringbone structures, it produces a whirlpool-like effect [2]. As a result, exosomes are more reliably swept into contact with the biosensors.

The team’s distinctive herringbone structures also increase the surface area within the chip. Because the surface is also porous, it allows fluid to drain out slowly to further encourage exosomes to reach the biosensors.

Zeng’s team put their “lab-on-a-chip” to the test using blood samples from 20 patients with ovarian cancer and 10 age-matched controls. The chip was able to detect rapidly the presence of exosomal proteins known to be associated with ovarian cancer.

The researchers report that their device is sensitive enough to detect just 10 exosomes in a 1-microliter sample. It also could be easily adapted to detect exosomal proteins associated with other cancers, and perhaps other conditions as well.

Zeng and colleagues haven’t mentioned whether they’re also looking into trying other geometric patterns in their designs. But the next time you see a tweed jacket, just remember that there’s more to its herringbone pattern than meets the eye.

References:

[1] Ultrasensitive microfluidic analysis of circulating exosomes using a nanostructured graphene oxide/polydopamine coating. Zhang P, He M, Zeng Y. Lab Chip. 2016 Aug 2;16(16):3033-3042.

[2] Ultrasensitive detection of circulating exosomes with a 3D-nanopatterned microfluidic chip. Zhang P, Zhou X, He M, Shang Y, Tetlow AL, Godwin AK, Zeng Y. Nature Biomedical Engineering. February 25, 2019.

Links:

Ovarian, Fallopian Tube, and Primary Peritoneal Cancer—Patient Version (National Cancer Institute/NIH)

Cancer Screening Overview—Patient Version (NCI/NIH)

Extracellular RNA Communication (Common Fund/NIH)

Zeng Lab (University of Kansas, Lawrence)

Godwin Laboratory (University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City)

NIH Support: National Cancer Institute

New ‘Liquid Biopsy’ Shows Early Promise in Detecting Cancer

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

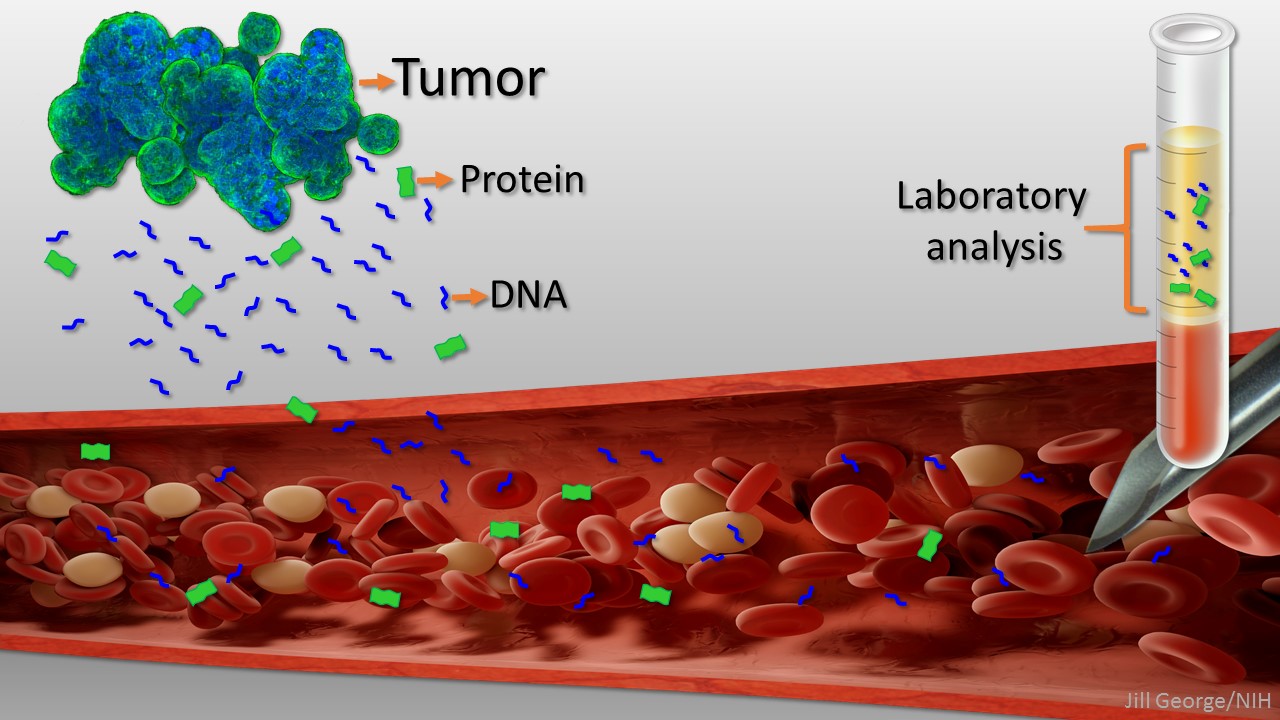

Caption: Liquid biopsy. Tumor cells shed protein and DNA into bloodstream for laboratory analysis and early cancer detection.

Early detection usually offers the best chance to beat cancer. Unfortunately, many tumors aren’t caught until they’ve grown relatively large and spread to other parts of the body. That’s why researchers have worked so tirelessly to develop new and more effective ways of screening for cancer as early as possible. One innovative approach, called “liquid biopsy,” screens for specific molecules that tumors release into the bloodstream.

Recently, an NIH-funded research team reported some encouraging results using a “universal” liquid biopsy called CancerSEEK [1]. By analyzing samples of a person’s blood for eight proteins and segments of 16 genes, CancerSEEK was able to detect most cases of eight different kinds of cancer, including some highly lethal forms—such as pancreatic, ovarian, and liver—that currently lack screening tests.

In a study of 1,005 people known to have one of eight early-stage tumor types, CancerSEEK detected the cancer in blood about 70 percent of the time, which is among the best performances to date for a blood test. Importantly, when CancerSEEK was performed on 812 healthy people without cancer, the test rarely delivered a false-positive result. The test can also be run relatively cheaply, at an estimated cost of less than $500.

Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancers: Moving Toward More Precise Prevention

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: “Homologous Hope” sculpture at University of Pennsylvania depicting the part of the BRCA2 gene involved in DNA repair.

Credit: Dan Burke Photography/Penn Medicine

Inherited mutations in the BRCA1 gene and closely related BRCA2 gene account for about 5 to 10 percent of all breast cancers and 15 percent of ovarian cancers [1]. For any given individual, the likelihood that one of these mutations is responsible goes up significantly in the presence of a strong family history of developing such cancers at a relatively early age. Recently, actress Angelina Jolie revealed that she’d had her ovaries removed to reduce her risk of ovarian cancer—news that follows her courageous disclosure a couple of years ago that she’d undergone a prophylactic double mastectomy after learning she’d inherited a mutated version of BRCA1.

As life-saving as genetic testing and preventive surgery may be for certain individuals, it remains unclear exactly which women with BRCA1/2 mutations stand to benefit from these drastic measures. For example, it’s been estimated that about 65 percent of women born with a BRCA1 mutation will develop invasive breast cancer over the course of their lives—which means approximately 35 percent will not. How can women in this situation be provided with more precise, individualized guidance on cancer prevention? An international team, led by NIH-funded researchers at the University of Pennsylvania, recently took an important first step towards answering that complex question.

Creative Minds: Interpreting Your Genome

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Just this year, we’ve reached the point where we can sequence an entire human genome for less than $1,000. That’s great news—and rather astounding, since the first human genome sequence (finished in 2003) cost an estimated $400,000,000! Does that mean we’ll be able to use each person’s unique genetic blueprint to guide his or her health care from cradle to grave? Maybe eventually, but it’s not quite as simple as it sounds.

Before we can use your genome to develop more personalized strategies for detecting, treating, and preventing disease, we need to be able to interpret the many variations that make your genome distinct from everybody else’s. While most of these variations are neither bad nor good, some raise the risk of particular diseases, and others serve to lower the risk. How do we figure out which is which?

Jay Shendure, an associate professor at the University of Washington in Seattle, has an audacious plan to figure this out, which is why he is among the 2013 recipients of the NIH Director’s Pioneer Award.

Different Cancers Can Share Genetic Signatures

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Cancer is a disease of the genome. It arises when genes involved in promoting or suppressing cell growth sustain mutations that disturb the normal stop and go signals. There are more than 100 different types of cancer, most of which derive their names and current treatment based on their tissue of origin—breast, colon, or brain, for example. But because of advances in DNA sequencing and analysis, that soon may be about to change.

Using data generated through The Cancer Genome Atlas, NIH-funded researchers recently compared the genomic fingerprints of tumor samples from nearly 3,300 patients with 12 types of cancer: acute myeloid leukemia, bladder, brain (glioblastoma multiforme), breast, colon, endometrial, head and neck, kidney, lung (adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma), ovarian, and rectal. Confirming but greatly extending what smaller studies have shown, the researchers discovered that even when cancers originate from vastly different tissues, they can show similar features at the DNA level