esophageal cancer

A Global Look at Cancer Genomes

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Cancer is a disease of the genome. It can be driven by many different types of DNA misspellings and rearrangements, which can cause cells to grow uncontrollably. While the first oncogenes with the potential to cause cancer were discovered more than 35 years ago, it’s been a long slog to catalog the universe of these potential DNA contributors to malignancy, let alone explore how they might inform diagnosis and treatment. So, I’m thrilled that an international team has completed the most comprehensive study to date of the entire genomes—the complete sets of DNA—of 38 different types of cancer.

Among the team’s most important discoveries is that the vast majority of tumors—about 95 percent—contained at least one identifiable spelling change in their genomes that appeared to drive the cancer [1]. That’s significantly higher than the level of “driver mutations” found in past studies that analyzed only a tumor’s exome, the small fraction of the genome that codes for proteins. Because many cancer drugs are designed to target specific proteins affected by driver mutations, the new findings indicate it may be worthwhile, perhaps even life-saving in many cases, to sequence the entire tumor genomes of a great many more people with cancer.

The latest findings, detailed in an impressive collection of 23 papers published in Nature and its affiliated journals, come from the international Pan-Cancer Analysis of Whole Genomes (PCAWG) Consortium. Also known as the Pan-Cancer Project for short, it builds on earlier efforts to characterize the genomes of many cancer types, including NIH’s The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and the International Cancer Genome Consortium (ICGC).

In these latest studies, a team including more than 1,300 researchers from around the world analyzed the complete genomes of more than 2,600 cancer samples. Those samples included tumors of the brain, skin, esophagus, liver, and more, along with matched healthy cells taken from the same individuals.

In each of the resulting new studies, teams of researchers dug deep into various aspects of the cancer DNA findings to make a series of important inferences and discoveries. Here are a few intriguing highlights:

• The average cancer genome was found to contain not just one driver mutation, but four or five.

• About 13 percent of those driver mutations were found in so-called non-coding DNA, portions of the genome that don’t code for proteins [2].

• The mutations arose within about 100 different molecular processes, as indicated by their unique patterns or “mutational signatures.” [3,4].

• Some of those signatures are associated with known cancer causes, including aberrant DNA repair and exposure to known carcinogens, such as tobacco smoke or UV light. Interestingly, many others are as-yet unexplained, suggesting there’s more to learn with potentially important implications for cancer prevention and drug development.

• A comprehensive analysis of 47 million genetic changes pieced together the chronology of cancer-causing mutations. This work revealed that many driver mutations occur years, if not decades, prior to a cancer’s diagnosis, a discovery with potentially important implications for early cancer detection [5].

The findings represent a big step toward cataloging all the major cancer-causing mutations with important implications for the future of precision cancer care. And yet, the fact that the drivers in 5 percent of cancers continue to remain mysterious (though they do have RNA abnormalities) comes as a reminder that there’s still a lot more work to do. The challenging next steps include connecting the cancer genome data to treatments and building meaningful predictors of patient outcomes.

To help in these endeavors, the Pan-Cancer Project has made all of its data and analytic tools available to the research community. As researchers at NIH and around the world continue to detail the diverse genetic drivers of cancer and the molecular processes that contribute to them, there is hope that these findings and others will ultimately vanquish, or at least rein in, this Emperor of All Maladies.

References:

[1] Pan-Cancer analysis of whole genomes. ICGC/TCGA Pan-Cancer Analysis of Whole Genomes Consortium. Nature. 2020 Feb;578(7793):82-93.

[2] Analyses of non-coding somatic drivers in 2,658 cancer whole genomes. Rheinbay E et al; PCAWG Consortium. Nature. 2020 Feb;578(7793):102-111.

[3] The repertoire of mutational signatures in human cancer. Alexandrov LB et al; PCAWG Consortium. Nature. 2020 Feb;578(7793):94-101.

[4] Patterns of somatic structural variation in human cancer genomes. Li Y et al; PCAWG Consortium. Nature. 2020 Feb;578(7793):112-121.

[5] The evolutionary history of 2,658 cancers. Gerstung M, Jolly C, Leshchiner I, Dentro SC et al; PCAWG Consortium. Nature. 2020 Feb;578(7793):122-128.

Links:

The Genetics of Cancer (National Cancer Institute/NIH)

Precision Medicine in Cancer Treatment (NCI)

The Cancer Genome Atlas Program (NIH)

NCI and the Precision Medicine Initiative (NCI)

NIH Support: National Cancer Institute, National Human Genome Research Institute

Panel Finds Exercise May Lower Cancer Risk, Improve Outcomes

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Exercise can work wonders for your health, including strengthening muscles and bones, and boosting metabolism, mood, and memory skills. Now comes word that staying active may also help to lower your odds of developing cancer.

After reviewing the scientific evidence, a panel of experts recently concluded that physical activity is associated with reduced risks for seven common types of cancer: colon, breast, kidney, endometrial, bladder, stomach, and esophageal adenocarcinoma. What’s more, the experts found that exercise—both before and after a cancer diagnosis—was linked to improved survival among people with breast, colorectal, or prostate cancers.

About a decade ago, the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) convened its first panel of experts to review the evidence on the role of exercise in cancer. At the time, there was limited evidence to suggest a connection between exercise and a reduced risk for breast, colon, and perhaps a few other cancer types. There also were some hints that exercise might help to improve survival among people with a diagnosis of cancer.

Today, the evidence linking exercise and cancer has grown considerably. That’s why the ACSM last year convened a group of 40 experts to perform a comprehensive review of the research literature and summarize the level of the evidence. The team, including Charles Matthews and Frank Perna with the NIH’s National Cancer Institute, reported its findings and associated guidelines and recommendations in three papers just published in Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise and CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians [1,2,3].

Here are some additional highlights from the papers:

There’s moderate evidence to support an association between exercise and reduced risk for some other cancer types, including cancers of the lung and liver.

While the optimal amount of exercise needed to reduce cancer risk is still unclear, being physically active is clearly one of the most important steps in general that people of all ages and abilities can take.

Is sitting the new smoking? Reducing the amount of time spent sitting also may help to lower the risk of some cancers, including endometrial, colon, and lung cancers. However, there’s not enough evidence to draw clear conclusions yet.

Every cancer survivor should, within reason, “avoid inactivity.” There’s plenty of evidence to show that aerobic and resistance exercise training improves many cancer-related health outcomes, reducing anxiety, depression, and fatigue while improving physical functioning and quality of life.

Physical activity before and after a diagnosis of cancer also may help to improve survival in some cancers, with perhaps the greatest benefits coming from exercise during and/or after cancer treatment.

Based on the evidence, the panel recommends that cancer survivors engage in moderate-intensity exercise, including aerobic and resistance training, at least two to three times a week. They should exercise for about 30 minutes per session.

The recommendation is based on added confirmation that exercise is generally safe for cancer survivors. The data indicate exercise can lead to improvements in anxiety, depression, fatigue, overall quality of life, and in some cases survival.

The panel also recommends that treatment teams and fitness professionals more systematically incorporate “exercise prescriptions” into cancer care. They should develop the resources to design exercise prescriptions that deliver the right amount of exercise to meet the specific needs, preferences, and abilities of people with cancer.

The ACSM has launched the “Moving Through Cancer” initiative. This initiative will help raise awareness about the importance of exercise during cancer treatment and help support doctors in advising their patients on those benefits.

It’s worth noting that there are still many fascinating questions to explore. While exercise is known to support better health in a variety of ways, correlation is not the same as causation. Questions remain about the underlying mechanisms that may help to explain the observed associations between physical activity, lowered cancer risk, and improved cancer survival.

An intensive NIH research effort, called the Molecular Transducers of Physical Activity Consortium (MoTrPAC), is underway to identify molecular mechanisms that might explain the wide-ranging benefits of physical exercise. It might well shed light on cancer, too.

As that evidence continues to come in, the findings are yet another reminder of the importance of exercise to our health. Everybody—people who are healthy, those with cancer, and cancer survivors alike—should make an extra effort to remain as physically active as our ages, abilities, and current health will allow. If I needed any more motivation to keep up my program of vigorous exercise twice a week, guided by an experienced trainer, here it is!

References:

[1] Exercise Is Medicine in Oncology: Engaging Clinicians to Help Patients Move Through Cancer. Schmitz KH, Campbell AM, Stuiver MM, Pinto BM, Schwartz AL, Morris GS, Ligibel JA, Cheville A, Galvão, DA, Alfano CM, Patel AV, Hue T, Gerber LH, Sallis R, Gusani NJ, Stout NL, Chan L, Flowers F, Doyle C, Helmrich S, Bain W, Sokolof J, Winters-Stone KM, Campbell KL, Matthews CE. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019 Oct 16 [Epub ahead of publication]

[2] American College of Sports Medicine Roundtable Report on Physical Activity, Sedentary Behavior, and Cancer Prevention and Control. Patel AV, Friedenreich CM, Moore SC, Hayes SC, Silver JK, Campbell KL, Gerber LH, George SM, Fulton JE, Denlinger C, Morris GS, Hue T, Schmitz KH, Matthews CE. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2019 Oct 16. [Epub ahead of publication]

[3] Exercise Guidelines for Cancer Survivors: Consensus Statement from International Multidisciplinary Roundtable. Campbell KL, Winters-Stone KM, Wiskemann J, May AM, Schwartz AL, Courneya KS, Zucker DS, Matthews CE, Ligibel JA, Gerber LH, Morris GS, Patel AV, Hue TF, Perna FM, Schmitz KH. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2019 Oct 16. [Epub ahead of publication]

Links:

Physical Activity and Cancer (National Cancer Institute/NIH)

Moving Through Cancer (American College of Sports Medicine, Indianapolis, IN)

American College of Sports Medicine

Charles Matthews (NCI)

Frank Perna (NCI)

NIH Support: National Cancer Institute

New ‘Liquid Biopsy’ Shows Early Promise in Detecting Cancer

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

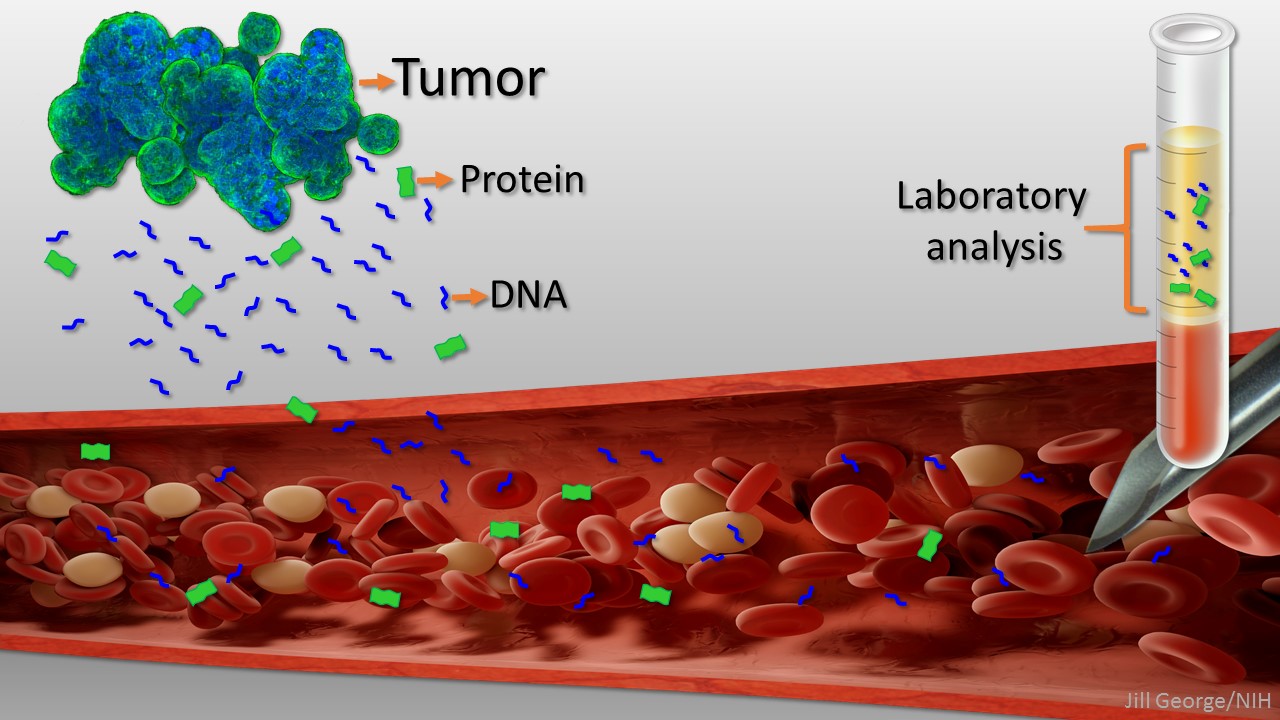

Caption: Liquid biopsy. Tumor cells shed protein and DNA into bloodstream for laboratory analysis and early cancer detection.

Early detection usually offers the best chance to beat cancer. Unfortunately, many tumors aren’t caught until they’ve grown relatively large and spread to other parts of the body. That’s why researchers have worked so tirelessly to develop new and more effective ways of screening for cancer as early as possible. One innovative approach, called “liquid biopsy,” screens for specific molecules that tumors release into the bloodstream.

Recently, an NIH-funded research team reported some encouraging results using a “universal” liquid biopsy called CancerSEEK [1]. By analyzing samples of a person’s blood for eight proteins and segments of 16 genes, CancerSEEK was able to detect most cases of eight different kinds of cancer, including some highly lethal forms—such as pancreatic, ovarian, and liver—that currently lack screening tests.

In a study of 1,005 people known to have one of eight early-stage tumor types, CancerSEEK detected the cancer in blood about 70 percent of the time, which is among the best performances to date for a blood test. Importantly, when CancerSEEK was performed on 812 healthy people without cancer, the test rarely delivered a false-positive result. The test can also be run relatively cheaply, at an estimated cost of less than $500.