beta cells

Uncovering Disease-Driving Events that Lead to Type 2 Diabetes

Posted on by Dr. Monica M. Bertagnolli

Nearly 35 million people in communities across the U.S. have type 2 diabetes (T2D), putting them at increased risk for a wide range of serious health complications, including vision loss, kidney failure, heart disease, stroke, and premature death.1 While we know a lot about the lifestyle and genetic factors that influence diabetes risk and steps that can help prevent or control it, there’s still a lot to learn about the precise early events in the body that drive this disease.

When you have T2D, the insulin-producing beta cells in your pancreas don’t release insulin in the way that they should. As a result, blood sugar doesn’t enter your cells, and its levels in the bloodstream go up. What’s less clear is exactly what happens to cause beta cells and the cell clusters where they’re found (called islets) to malfunction in the first place. However, I’m encouraged by some new NIH-supported research in Nature that used various large datasets to identify key signatures of islet dysfunction in people with T2D.2

Earlier studies have linked about 400 sites in the human genome to an increased risk for T2D. But most of them—more than 9 in 10—are primarily in noncoding stretches of DNA that control genes. As a result, it’s been hard to figure out exactly how those genetic variants that increase risk in the general population lead to the changes in individuals who go on to develop T2D.

In the new study, a team led by Marcela Brissova and Alvin C. Powers, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, and Stephen C.J. Parker, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, used sophisticated analytic approaches to study changes within pancreatic tissues and islets taken from donors who’d had early-stage T2D at the time of their death. They included tissues from donors without T2D to serve as a comparison.

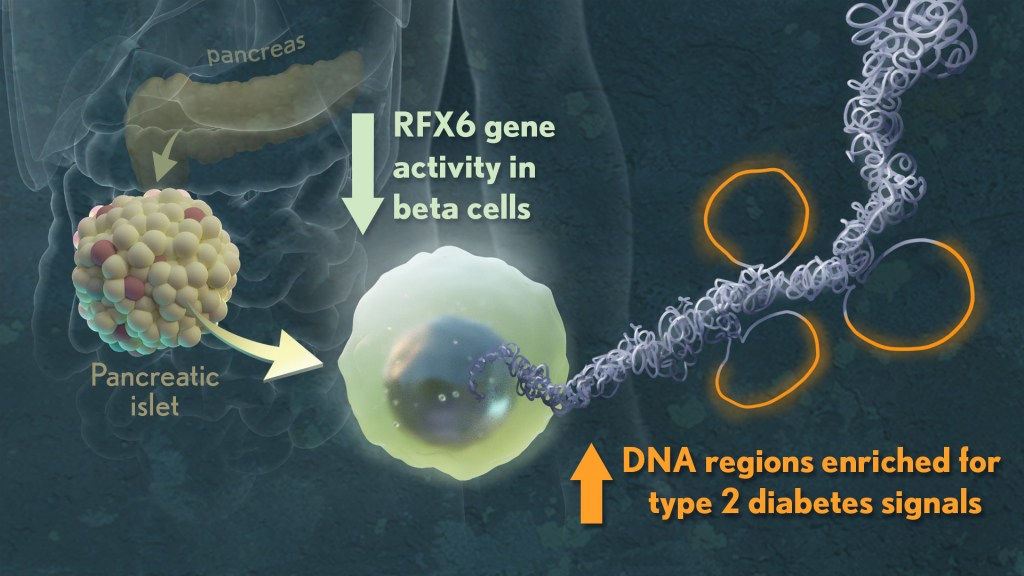

To get a better understanding, they looked at the tissues in multiple ways, studying differences in their basic physiology, gene activity, and cellular-level structures. By integrating data on these observed differences with other types of data from prior studies, they showed that impaired function of beta cells is a hallmark of early T2D, reinforcing prior evidence. Other pancreatic islet cell types appeared mostly unchanged.

Their studies also showed that alterations in a particular gene network are key in early-stage T2D. The network, controlled by a protein called RFX6, cause pancreatic beta cells to malfunction. The researchers performed additional studies that showed lowering RFX6 levels led beta cells to secrete less insulin. Lower RFX6 levels also led to structural changes in the DNA, specifically in sites that have known links to diabetes risk. They expanded this finding by doing a population-scale genetic analysis. Using genetic information for more than 500,000 volunteers available in the UK biobank, they showed a causal link between lower levels of RFX6 and T2D.

Further study is needed to understand what’s behind the initial changes in RFX6. The researchers also want to explore further whether RFX6 might be a promising target for new treatments to prevent or reverse early-stage molecular and functional defects in the beta cell that underlie T2D. The researchers note that they have made all the data publicly available through user-friendly and interactive web portals, in hopes it will lead to more answers for the millions already affected by T2D and so many others who may be at risk.

References:

[2] JT Walker, DC Saunders, V Rai, et al. Genetic risk converges on regulatory networks mediating early type 2 diabetes. Nature. DOI: 10.1038/s41586-023-06693-2 (2023).

NIH Support: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Eye Institute, National Institute of General Medical Sciences

How COVID-19 Can Lead to Diabetes

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Along with the pneumonia, blood clots, and other serious health concerns caused by SARS-CoV-2, the COVID-19 virus, some studies have also identified another troubling connection. Some people can develop diabetes after an acute COVID-19 infection.

What’s going on? Two new NIH-supported studies, now available as pre-proofs in the journal Cell Metabolism [1,2], help to answer this important question, confirming that SARS-CoV-2 can target and impair the body’s insulin-producing cells.

Type 1 diabetes occurs when beta cells in the pancreas don’t secrete enough insulin to allow the body to metabolize food optimally after a meal. As a result of this insulin insufficiency, blood glucose levels go up, the hallmark of diabetes.

Earlier lab studies had suggested that SARS-CoV-2 can infect human beta cells [3]. They also showed that this dangerous virus can replicate in these insulin-producing beta cells, to make more copies of itself and spread to other cells [4].

The latest work builds on these earlier studies to discover more about the connection between COVID-19 and diabetes. The work involved two independent NIH-funded teams, one led by Peter Jackson, Stanford University School of Medicine, Palo Alto, CA, and the other by Shuibing Chen, Weill Cornell Medicine, New York. I’m actually among the co-authors on the study by the Chen team, as some of the studies were conducted in my lab at NIH’s National Human Genome Research Institute, Bethesda, MD.

Both studies confirmed infection of pancreatic beta cells in autopsy samples from people who died of COVID-19. Additional studies by the Jackson team suggest that the coronavirus may preferentially infect the insulin-producing beta cells.

This also makes biological sense. Beta cells and other cell types in the pancreas express the ACE2 receptor protein, the TMPRSS2 enzyme protein, and neuropilin 1 (NRP1), all of which SARS-CoV-2 depends upon to enter and infect human cells. Indeed, the Chen team saw signs of the coronavirus in both insulin-producing beta cells and several other pancreatic cell types in the studies of autopsied pancreatic tissue.

The new findings also show that the coronavirus infection changes the function of islets—the pancreatic tissue that contains beta cells. Both teams report evidence that infection with SARS-CoV-2 leads to reduced production and release of insulin from pancreatic islet tissue. The Jackson team also found that the infection leads directly to the death of some of those all-important beta cells. Encouragingly, they showed this could avoided by blocking NRP1.

In addition to the loss of beta cells, the infection also appears to change the fate of the surviving cells. Chen’s team performed single-cell analysis to get a careful look at changes in the gene activity within pancreatic cells following SARS-CoV-2 infection. These studies showed that beta cells go through a process of transdifferentiation, in which they appeared to get reprogrammed.

In this process, the cells begin producing less insulin and more glucagon, a hormone that encourages glycogen in the liver to be broken down into glucose. They also began producing higher levels of a digestive enzyme called trypsin 1. Importantly, they also showed that this transdifferentiation process could be reversed by a chemical (called trans-ISRIB) known to reduce an important cellular response to stress.

The consequences of this transdifferentiation of beta cells aren’t yet clear, but would be predicted to worsen insulin deficiency and raise blood glucose levels. More study is needed to understand how SARS-CoV-2 reaches the pancreas and what role the immune system might play in the resulting damage. Above all, this work provides yet another reminder of the importance of protecting yourself, your family members, and your community from COVID-19 by getting vaccinated if you haven’t already—and encouraging your loved ones to do the same.

References:

[1] SARS-CoV-2 infection induces beta cell transdifferentiation. Tang et al. Cell Metab 2021 May 19;S1550-4131(21)00232-1.

[2] SARS-CoV-2 infects human pancreatic beta cells and elicits beta cell impairment. Wu et al. Cell Metab. 2021 May 18;S1550-4131(21)00230-8.

[3] A human pluripotent stem cell-based platform to study SARS-CoV-2 tropism and model virus infection in human cells and organoids. Yang L, Han Y, Nilsson-Payant BE, Evans T, Schwartz RE, Chen S, et al. Cell Stem Cell. 2020 Jul 2;27(1):125-136.e7.

[4] SARS-CoV-2 infects and replicates in cells of the human endocrine and exocrine pancreas. Müller JA, Groß R, Conzelmann C, Münch J, Heller S, Kleger A, et al. Nat Metab. 2021 Feb;3(2):149-165.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Type 1 Diabetes (National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Disorders/NIH)

Jackson Lab (Stanford Medicine, Palo Alto, CA)

Shuibing Chen Laboratory (Weill Cornell Medicine, New York City)

NIH Support: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; National Human Genome Research Institute; National Institute of General Medical Sciences; National Cancer Institute; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development

Insulin-Producing Organoids Offer Hope for Treating Type 1 Diabetes

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

For the 1 to 3 million Americans with type 1 diabetes, the immune system destroys insulin-producing beta cells of the pancreas that control the amount of glucose in the bloodstream. As a result, these individuals must monitor their blood glucose often and take replacement doses of insulin to keep it under control. Such constant attention, combined with a strict diet to control sugar intake, is challenging—especially for children.

For some people with type 1 diabetes, there is another option. They can be treated—maybe even cured—with a pancreatic islet cell transplant from an organ donor. These transplanted islet cells, which harbor the needed beta cells, can increase insulin production. But there’s a big catch: there aren’t nearly enough organs to go around, and people who receive a transplant must take lifelong medications to keep their immune system from rejecting the donated organ.

Now, NIH-funded scientists, led by Ronald Evans of the Salk Institute, La Jolla, CA, have devised a possible workaround: human islet-like organoids (HILOs) [1]. These tiny replicas of pancreatic tissue are created in the laboratory, and you can see them above secreting insulin (green) in a lab dish. Remarkably, some of these HILOs have been outfitted with a Harry Potter-esque invisibility cloak to enable them to evade immune attack when transplanted into mice.

Over several years, Doug Melton’s lab at Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, has worked steadily to coax induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells, which are made from adult skin or blood cells, to form miniature islet-like cells in a lab dish [2]. My own lab at NIH has also been seeing steady progress in this effort, working with collaborators at the New York Stem Cell Foundation.

Although several years ago researchers could get beta cells to make insulin, they wouldn’t secrete the hormone efficiently when transplanted into a living mouse. About four years ago, the Evans lab found a possible solution by uncovering a genetic switch called ERR-gamma that when flipped, powered up the engineered beta cells to respond continuously to glucose and release insulin [3].

In the latest study, Evans and his team developed a method to program HILOs in the lab to resemble actual islets. They did it by growing the insulin-producing cells alongside each other in a gelatinous, three-dimensional chamber. There, the cells combined to form organoid structures resembling the shape and contour of the islet cells seen in an actual 3D human pancreas. After they are switched on with a special recipe of growth factors and hormones, these activated HILOs secrete insulin when exposed to glucose. When transplanted into a living mouse, this process appears to operate just like human beta cells work inside a human pancreas.

Another major advance was the invisibility cloak. The Salk team borrowed the idea from cancer immunotherapy and a type of drug called a checkpoint inhibitor. These drugs harness the body’s own immune T cells to attack cancer. They start with the recognition that T cells display a protein on their surface called PD-1. When T cells interact with other cells in the body, PD-1 binds to a protein on the surface of those cells called PD-L1. This protein tells the T cells not to attack. Checkpoint inhibitors work by blocking the interaction of PD-1 and PD-L1, freeing up immune cells to fight cancer.

Reversing this logic for the pancreas, the Salk team engineered HILOs to express PD-L1 on their surface as a sign to the immune system not to attack. The researchers then transplanted these HILOs into diabetic mice that received no immunosuppressive drugs, as would normally be the case to prevent rejection of these human cells. Not only did the transplanted HILOs produce insulin in response to glucose spikes, they spurred no immune response.

So far, HILOs transplants have been used to treat diabetes for more than 50 days in diabetic mice. More research will be needed to see whether the organoids can function for even longer periods of time.

Still, this is exciting news, and provides an excellent example of how advances in one area of science can provide new possibilities for others. In this case, these insights provide fresh hope for a day when children and adults with type 1 diabetes can live long, healthy lives without the need for frequent insulin injections.

References:

[1] Immune-evasive human islet-like organoids ameliorate diabetes. [published online ahead of print, 2020 Aug 19]. Yoshihara E, O’Connor C, Gasser E, Wei Z, Oh TG, Tseng TW, Wang D, Cayabyab F, Dai Y, Yu RT, Liddle C, Atkins AR, Downes M, Evans RM. Nature. 2020 Aug 19. [Epub ahead of publication]

[2] Generation of Functional Human Pancreatic β Cells In Vitro. Pagliuca FW, Millman JR, Gürtler M, Segel M, Van Dervort A, Ryu JH, Peterson QP, Greiner D, Melton DA. Cell. 2014 Oct 9;159(2):428-39.

[3] ERRγ is required for the metabolic maturation of therapeutically functional glucose-responsive β cells. Yoshihara E, Wei Z, Lin CS, Fang S, Ahmadian M, Kida Y, Tseng T, Dai Y, Yu RT, Liddle C, Atkins AR, Downes M, Evans RM. Cell Metab. 2016 Apr 12; 23(4):622-634.

Links:

Type 1 Diabetes (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases/NIH)

Pancreatic Islet Transplantation (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases)

“The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2012” for Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells, The Nobel Prize news release, October 8, 2012.

Evans Lab (Salk Institute, La Jolla, CA)

NIH Support: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; National Cancer Institute

Study in Africa Yields New Diabetes Gene

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

When I volunteered to serve as a physician at a hospital in rural Nigeria more than 25 years ago, I expected to treat a lot of folks with infectious diseases, such as malaria and tuberculosis. And that certainly happened. What I didn’t expect was how many people needed care for type 2 diabetes (T2D) and the health problems it causes. Surprisingly, these individuals were generally not overweight, and the course of their illness seemed different than in the West.

The experience inspired me to join with other colleagues at Howard University, Washington, DC, to help found the Africa America Diabetes Mellitus (AADM) study. It aims to uncover genomic risk factors for T2D in Africa and, using that information, improve understanding of the condition around the world.

So, I’m pleased to report that, using genomic data from more than 5,000 volunteers, our AADM team recently discovered a new gene, called ZRANB3, that harbors a variant associated with T2D in sub-Saharan Africa [1]. Using sophisticated laboratory models, the team showed that a malfunctioning ZRANB3 gene impairs insulin production to control glucose levels in the bloodstream.

Since my first trip to Nigeria, the number of people with T2D has continued to rise. It’s now estimated that about 8 to 10 percent of Nigerians have some form of diabetes [2]. In Africa, diabetes affects more than 7 percent of the population, more than twice the incidence in 1980 [3].

The causes of T2D involve a complex interplay of genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors. I was particularly interested in finding out whether the genetic factors for T2D might be different in sub-Saharan Africa than in the West. But at the time, there was a dearth of genomic information about T2D in Africa, the cradle of humanity. To understand complex diseases like T2D fully, we need all peoples and continents represented in the research.

To begin to fill this research gap, the AADM team got underway and hasn’t looked back. In the latest study, led by Charles Rotimi at NIH’s National Human Genome Research Institute, in partnership with multiple African diabetes experts, the AADM team enlisted 5,231 volunteers from Nigeria, Ghana, and Kenya. About half of the study’s participants had T2D and half did not.

As reported in Nature Communications, their genome-wide search for T2D gene variants turned up three interesting finds. Two were in genes previously linked to T2D risk in other human populations. The third involved a gene that codes for ZRANB3, an enzyme associated with DNA replication and repair that had never been reported in association with T2D.

To understand how ZRANB3 might influence a person’s risk for developing T2D, the researchers turned to zebrafish (Danio rerio), an excellent vertebrate model for its rapid development. The researchers found that the ZRANB3 gene is active in insulin-producing beta cells of the pancreas. That was important to know because people with T2D frequently have reduced numbers of beta cells, which compromises their ability to produce enough insulin.

The team next used CRISPR/Cas9 gene-editing tools either to “knock out” or reduce the expression of ZRANB3 in young zebrafish. In both cases, it led to increased loss of beta cells.

Additional study in the beta cells of mice provided more details. While normal beta cells released insulin in response to high levels of glucose, those with suppressed ZRANB3 activity couldn’t. Together, the findings show that ZRANB3 is important for beta cells to survive and function normally. It stands to reason, then, that people with a lower functioning variant of ZRANB3 would be more susceptible to T2D.

In many cases, T2D can be managed with some combination of diet, exercise, and oral medications. But some people require insulin to manage the disease. The new findings suggest, particularly for people of African ancestry, that the variant of the ZRANB3 gene that one inherits might help to explain those differences. People carrying particular variants of this gene also may benefit from beginning insulin treatment earlier, before their beta cells have been depleted.

So why wasn’t ZRANB3 discovered in the many studies on T2D carried out in the United States, Europe, and Asia? It turns out that the variant that predisposes Africans to this disease is extremely rare in these other populations. Only by studying Africans could this insight be uncovered.

More than 20 years ago, I helped to start the AADM project to learn more about the genetic factors driving T2D in sub-Saharan Africa. Other dedicated AADM leaders have continued to build the research project, taking advantage of new technologies as they came along. It’s profoundly gratifying that this project has uncovered such an impressive new lead, revealing important aspects of human biology that otherwise would have been missed. The AADM team continues to enroll volunteers, and the coming years should bring even more discoveries about the genetic factors that contribute to T2D.

References:

[1] ZRANB3 is an African-specific type 2 diabetes locus associated with beta-cell mass and insulin response. Adeyemo AA, Zaghloul NA, Chen G, Doumatey AP, Leitch CC, Hostelley TL, Nesmith JE, Zhou J, Bentley AR, Shriner D, Fasanmade O, Okafor G, Eghan B Jr, Agyenim-Boateng K, Chandrasekharappa S, Adeleye J, Balogun W, Owusu S, Amoah A, Acheampong J, Johnson T, Oli J, Adebamowo C; South Africa Zulu Type 2 Diabetes Case-Control Study, Collins F, Dunston G, Rotimi CN. Nat Commun. 2019 Jul 19;10(1):3195.

[2] Diabetes mellitus in Nigeria: The past, present and future. Ogbera AO, Ekpebegh C. World J Diabetes. 2014 Dec 15;5(6):905-911.

[3] Global report on diabetes. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2016. World Health Organization.

Links:

Diabetes (National Institute of Diabetes ad Digestive and Kidney Diseases/NIH)

Diabetes and African Americans (Department of Health and Human Services)

Why Use Zebrafish to Study Human Diseases (Intramural Research Program/NIH)

Charles Rotimi (National Human Genome Research Institute/NIH)

NIH Support: National Human Genome Research Institute; National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities

Can Artificial Cells Take Over for Lost Insulin-Secreting Cells?

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: Artificial beta cell, made of a lipid bubble (purple) carrying smaller, insulin-filled vesicles (green). Imaged with cryo-scanning electron microscope (cryo-SEM) and colorized.

Credit: Zhen Gu Lab

People with diabetes have benefited tremendously from advances in monitoring and controlling blood sugar, but they’re still waiting and hoping for a cure. Some of the most exciting possibilities aim to replace the function of the insulin-secreting pancreatic beta cells that is deficient in diabetes. The latest strategy of this kind is called AβCs, short for artificial beta cells.

As you see in the cryo-SEM image above, AβCs are specially designed lipid bubbles, each of which contains hundreds of smaller, ball-like vesicles filled with insulin. The AβCs are engineered to “sense” a rise in blood glucose, triggering biochemical changes in the vesicle and the automatic release of some of its insulin load until blood glucose levels return to normal.

In recent studies of mice with type 1 diabetes, researchers partially supported by NIH found that a single injection of AβCs under the skin could control blood glucose levels for up to five days. With additional optimization and testing, the hope is that people with diabetes may someday be able to receive AβCs through patches that painlessly stick on their skin.

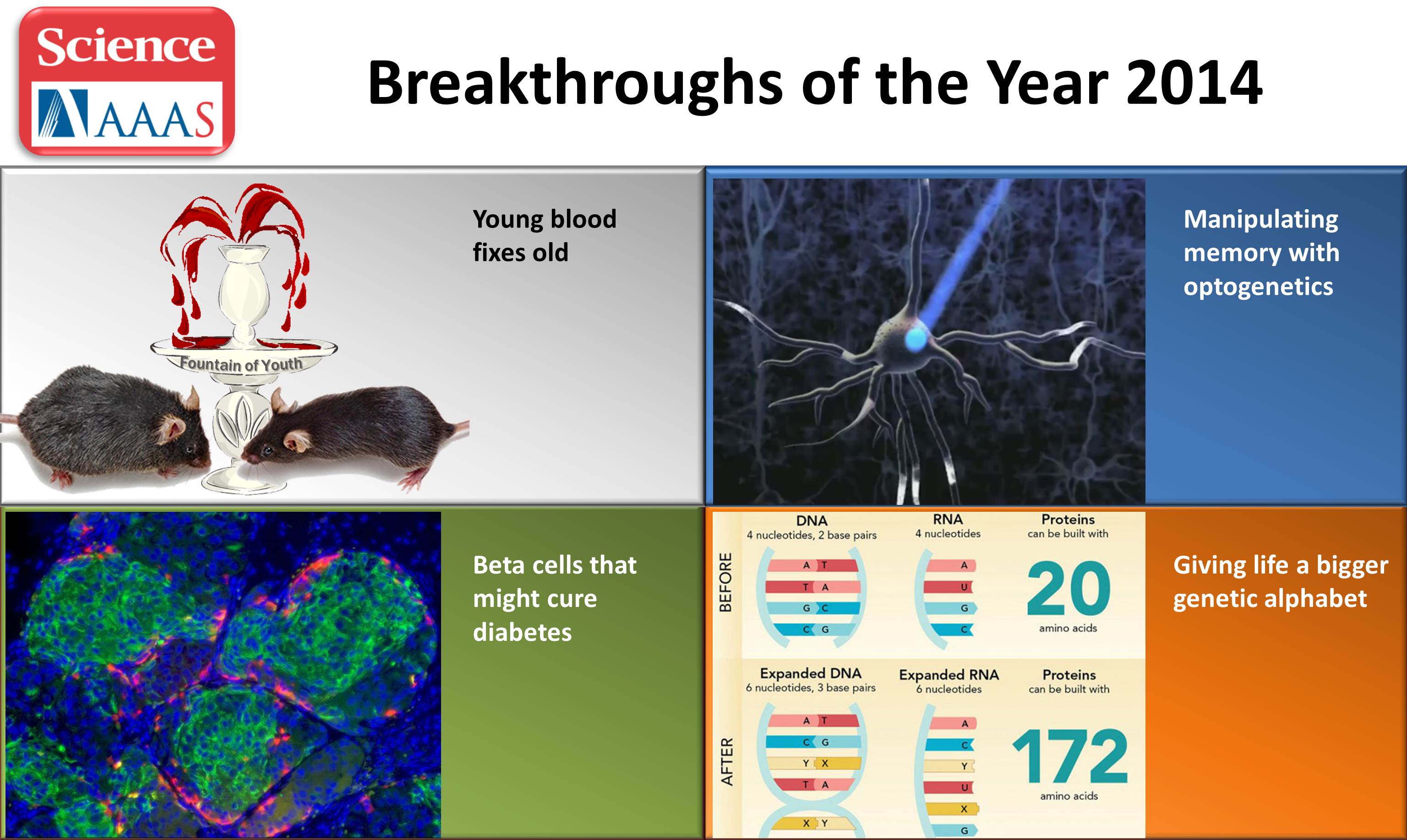

NIH-Funded Research Makes Science’s “Top 10” List

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Modeled after Time’s Person of the Year, the journal Science has a tradition of honoring the year’s most groundbreaking research advances. For 2014, the European Space Agency nabbed first place with the Rosetta spacecraft’s amazing landing on a comet. But biomedical science also was well represented on the “Top 10” list—with NIH helping to support at least four of the advances. So, while I’ve highlighted some of these in the past, I can’t think of a better way for the NIH Director to ring in the New Year than to take a brief look back at these remarkable achievements!

Youth serum for real? Spanish explorer Ponce de Leon may have never discovered the Fountain of Youth, but researchers have engineered an exciting new lead. Researchers fused the circulatory systems of young and old mice to create a shared blood supply. In the old mice, the young blood triggered new muscle and more neural connections, and follow-up studies revealed that their memory formation improved. The researchers discovered that a gene called Creb prompts the rejuvenation. Block the protein produced by Creb, and the young blood loses its anti-aging magic [1]. Another team discovered that a factor called GDF11 increased the number of neural stem cells and stimulated the growth of new blood vessels in the brains of older animals [2].

Stem Cell Science: Taking Aim at Type 1 Diabetes

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

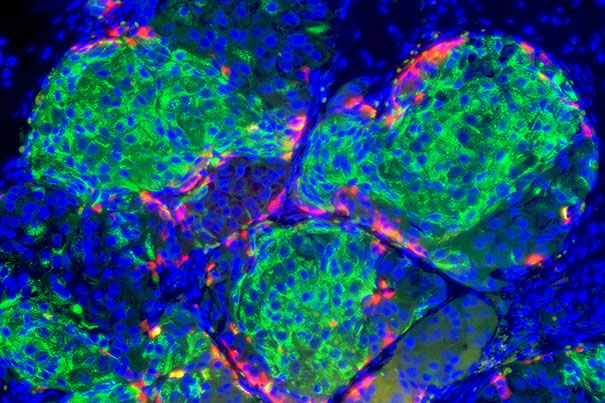

Caption: Insulin-producing pancreatic beta cells (green) derived from human embryonic stem cells that have formed islet-like clusters in a mouse. The red cells are producing another metabolic hormone, glucagon, that regulates blood glucose levels. Blue indicates cell nuclei.

Credit: Photo by B. D. Colen/Harvard Staff; Image courtesy of Doug Melton

For most of the estimated 1 to 3 million Americans living with type 1 diabetes, every day brings multiple fingerpricks to manage their blood glucose levels with replacement insulin [1,2]. The reason is that their own immune systems have somehow engaged in friendly fire on small, but vital, clusters of cells in the pancreas known as the islets—which harbor the so-called “beta cells” that make insulin. So, it’s no surprise that researchers seeking ways to help people with type 1 diabetes have spent decades trying a find a reliable way to replace these islets.

Islet replacement has proven to be an extremely difficult research challenge for a variety of reasons, but exciting opportunities are now on the horizon. Notably, a team of researchers, led by Douglas Melton of Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, and partially funded by NIH, reported groundbreaking success just last week in spurring a human embryonic stem cell (hESC) line and two human-induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cell lines to differentiate into the crucial, insulin-producing beta cells. Not only did cells generated from all three of these lines look like human pancreatic beta cells, they functioned like bona fide, glucose-responsive beta cells in a mouse model of type 1 diabetes [3].

More Beta Cells, More Insulin, Less Diabetes

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: Betatrophin, a natural hormone produced in liver and fat cells, triggers the insulin-producing beta cells in the pancreas to replicate

Credit: Douglas Melton and Peng Yi

Type 2 diabetes (T2D) has arguably reached epidemic levels in this country; between 22 and 24 million people suffer from the disease. But now there’s an exciting new development: scientists at the Harvard Stem Cell Institute have discovered a hormone that might slow or stop the progression of diabetes [1].

T2D is the most common type of diabetes, accounting for about 95% of cases. The hallmark is high blood sugar. It is linked to obesity, which increases the body’s demand for more and more insulin. T2D develops when specific insulin-producing cells in the pancreas, called beta cells, become exhausted and can’t keep up with the increased demand. With insufficient insulin, blood glucose levels rise. Over time, these high levels of glucose can lead to heart disease, stroke, blindness, kidney disease, nerve damage, and even amputations. T2D can be helped by weight loss and exercise, but often oral medication or insulin shots are ultimately needed.