21 Search Results for "muscular dystrophy"

More Progress Toward Gene Editing for Kids with Muscular Dystrophy

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Thanks to CRISPR and other gene editing technologies, hopes have never been greater for treating or even curing Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) and many other rare, genetic diseases that once seemed tragically out of reach. The latest encouraging news comes from a study in which a single infusion of a CRISPR editing system produced lasting benefits in a mouse model of DMD.

There currently is no way to cure DMD, an ultimately fatal disease that mainly affects boys. Caused by mutations in a gene that codes for a critical protein called dystrophin, DMD progressively weakens the skeletal and heart muscles. People with DMD are usually in wheelchairs by the age of 10, with most dying before the age of 30.

The exquisite targeting ability of CRISPR/Cas9 editing systems rely on a sequence-specific guide RNA to direct a scissor-like, bacterial enzyme (Cas9) to just the right spot in the genome, where it can be used to cut out, replace, or repair disease-causing mutations. In previous studies in mice and dogs, researchers directly infused CRISPR systems directly into the animals bodies. This “in vivo” approach to gene editing successfully restored production of functional dystrophin proteins, strengthening animals’ muscles within weeks of treatment.

But an important question remained: would CRISPR’s benefits persist over the long term? The answer in a mouse model of DMD appears to be “yes,” according to findings published recently in Nature Medicine by Charles Gersbach, Duke University, Durham, NC, and his colleagues [1]. Specifically, the NIH-funded team found that after mice with DMD received one infusion of a specially designed CRISPR/Cas9 system, the abnormal gene was edited in a way that restored dystrophin production in skeletal and heart muscles for more than a year. What’s more, lasting improvements were seen in the structure of the animals’ muscles throughout the same time period.

As exciting as these results may be, much more research is needed to explore both the safety and the efficacy of in vivo gene editing before it can be tried in humans with DMD. For instance, the researchers found that older mice that received the editing system developed an immune response to the bacterially-derived Cas9 protein. However, this response didn’t prevent the CRISPR/Cas9 system from doing its job or appear to cause any adverse effects. Interestingly, younger animals didn’t show such a response.

It’s worth noting that the immune systems of mice and people often respond quite differently. But the findings do highlight some possible challenges of such treatments, as well as approaches to reduce possible side effects. For instance, the latest findings suggest CRISPR/Cas9 treatment might best be done early in life, before an infant’s immune system is fully developed. Also, if it’s necessary to deliver CRISPR/Cas9 to older individuals, it may be beneficial to suppress the immune system temporarily.

Another concern about CRISPR technology is the potential for damaging, “off-target” edits to other parts of the genome. In the new work, the Duke team found that its CRISPR system made very few “off-target” edits. However, the system did make a surprising number of complex edits to the targeted dystrophin gene, including integration of the viral vector used to deliver Cas9. While those editing “errors” might reduce the efficacy of treatment, researchers said they didn’t appear to affect the health of the mice studied.

It’s important to emphasize that this gene editing research aimed at curing DMD is being done in non-reproductive (somatic) cells, primarily muscle tissue. The NIH does not support the use of gene editing technologies in human embryos or human reproductive (germline) cells, which would change the genetic makeup of future offspring.

As such, the Duke researchers’ CRISPR/Cas9 system is designed to work optimally in a range of muscle and muscle-progenitor cells. Still, they were able to detect editing of the dystrophin-producing gene in the liver, kidney, brain, and other tissues. Importantly, there was no evidence of edits in the germline cells of the mice. The researchers note that their CRISPR system can be reconfigured to limit gene editing to mature muscle cells, although that may reduce the treatment’s efficacy.

It’s truly encouraging to see that CRISPR gene editing may confer lasting benefits in an animal model of DMD, but a great many questions remain before trying this new approach in kids with DMD. But that time is coming—so let’s boldly go forth and get answers to those questions on behalf of all who are affected by this heartbreaking disease.

Reference:

[1] Long-term evaluation of AAV-CRISPR genome editing for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nelson CE, Wu Y, Gemberling MP, Oliver ML, Waller MA, Bohning JD, Robinson-Hamm JN, Bulaklak K, Castellanos Rivera RM, Collier JH, Asokan A, Gersbach CA. Nat Med. 2019 Feb 18.

Links:

Muscular Dystrophy Information Page (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke/NIH)

Gersbach Lab (Duke University, Durham, NC)

Somatic Cell Genome Editing (Common Fund/NIH)

NIH Support: National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases; National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering

Gene Editing in Dogs Boosts Hope for Kids with Muscular Dystrophy

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

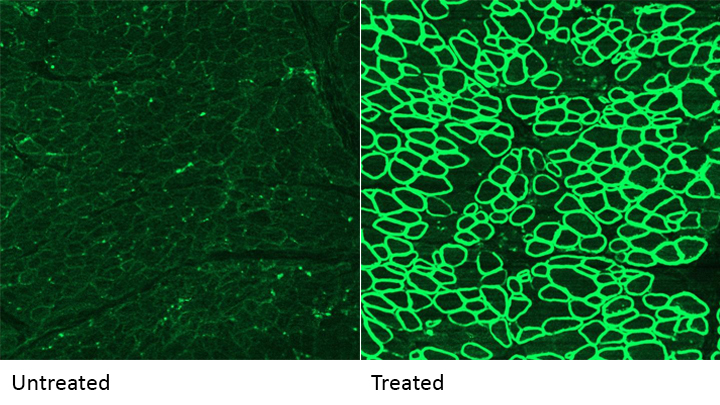

Caption: A CRISPR/cas9 gene editing-based treatment restored production of dystrophin proteins (green) in the diaphragm muscles of dogs with Duchenne muscular dystrophy.

Credit: UT Southwestern

CRISPR and other gene editing tools hold great promise for curing a wide range of devastating conditions caused by misspellings in DNA. Among the many looking to gene editing with hope are kids with Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), an uncommon and tragically fatal genetic disease in which their muscles—including skeletal muscles, the heart, and the main muscle used for breathing—gradually become too weak to function. Such hopes were recently buoyed by a new study that showed infusion of the CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing system could halt disease progression in a dog model of DMD.

As seen in the micrographs above, NIH-funded researchers were able to use the CRISPR/Cas9 editing system to restore production of a critical protein, called dystrophin, by up to 92 percent in the muscle tissue of affected dogs. While more study is needed before clinical trials could begin in humans, this is very exciting news, especially when one considers that boosting dystrophin levels by as little as 15 percent may be enough to provide significant benefit for kids with DMD.

Cool Videos: Myotonic Dystrophy

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Today, I’d like to share a video that tells the inspirational story of two young Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) researchers who are taking aim at a genetic disease that has touched both of their lives. Called myotonic dystrophy (DM), the disease is the most common form of muscular dystrophy in adults and causes a wide variety of health problems—including muscle wasting and weakness, irregular heartbeats, and profound fatigue.

If you’d like a few more details before or after watching these scientists’ video, here’s their description of their work: “Eric Wang started his lab at MIT in 2013 through receiving an NIH Early Independence Award. Learn about the path that led him to study myotonic dystrophy, a disease that affects his family. Eric’s team of researchers includes Ona McConnell, an avid field hockey goalie who is affected by myotonic dystrophy herself. Determined to make a difference, Eric and Ona hope to inspire others in their efforts to better understand and treat this disease.”

Links:

Engineering a Better Way to Deliver Therapeutic Genes to Muscles

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

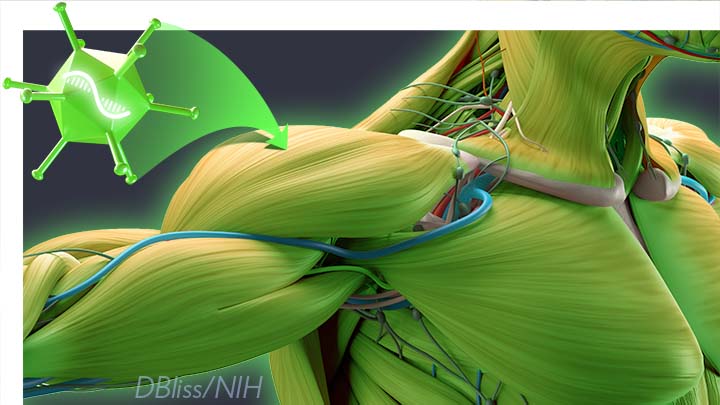

Amid all the progress toward ending the COVID-19 pandemic, it’s worth remembering that researchers here and around the world continue to make important advances in tackling many other serious health conditions. As an inspiring NIH-supported example, I’d like to share an advance on the use of gene therapy for treating genetic diseases that progressively degenerate muscle, such as Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD).

As published recently in the journal Cell, researchers have developed a promising approach to deliver therapeutic genes and gene editing tools to muscle more efficiently, thus requiring lower doses [1]. In animal studies, the new approach has targeted muscle far more effectively than existing strategies. It offers an exciting way forward to reduce unwanted side effects from off-target delivery, which has hampered the development of gene therapy for many conditions.

In boys born with DMD (it’s an X-linked disease and therefore affects males), skeletal and heart muscles progressively weaken due to mutations in a gene encoding a critical muscle protein called dystrophin. By age 10, most boys require a wheelchair. Sadly, their life expectancy remains less than 30 years.

The hope is gene therapies will one day treat or even cure DMD and allow people with the disease to live longer, high-quality lives. Unfortunately, the benign adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) traditionally used to deliver the healthy intact dystrophin gene into cells mostly end up in the liver—not in muscles. It’s also the case for gene therapy of many other muscle-wasting genetic diseases.

The heavy dose of viral vector to the liver is not without concern. Recently and tragically, there have been deaths in a high-dose AAV gene therapy trial for X-linked myotubular myopathy (XLMTM), a different disorder of skeletal muscle in which there may already be underlying liver disease, potentially increasing susceptibility to toxicity.

To correct this concerning routing error, researchers led by Mohammadsharif Tabebordbar in the lab of Pardis Sabeti, Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard and Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, have now assembled an optimized collection of AAVs. They have been refined to be about 10 times better at reaching muscle fibers than those now used in laboratory studies and clinical trials. In fact, researchers call them myotube AAVs, or MyoAAVs.

MyoAAVs can deliver therapeutic genes to muscle at much lower doses—up to 250 times lower than what’s needed with traditional AAVs. While this approach hasn’t yet been tried in people, animal studies show that MyoAAVs also largely avoid the liver, raising the prospect for more effective gene therapies without the risk of liver damage and other serious side effects.

In the Cell paper, the researchers demonstrate how they generated MyoAAVs, starting out with the commonly used AAV9. Their goal was to modify the outer protein shell, or capsid, to create an AAV that would be much better at specifically targeting muscle. To do so, they turned to their capsid engineering platform known as, appropriately enough, DELIVER. It’s short for Directed Evolution of AAV capsids Leveraging In Vivo Expression of transgene RNA.

Here’s how DELIVER works. The researchers generate millions of different AAV capsids by adding random strings of amino acids to the portion of the AAV9 capsid that binds to cells. They inject those modified AAVs into mice and then sequence the RNA from cells in muscle tissue throughout the body. The researchers want to identify AAVs that not only enter muscle cells but that also successfully deliver therapeutic genes into the nucleus to compensate for the damaged version of the gene.

This search delivered not just one AAV—it produced several related ones, all bearing a unique surface structure that enabled them specifically to target muscle cells. Then, in collaboration with Amy Wagers, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, the team tested their MyoAAV toolset in animal studies.

The first cargo, however, wasn’t a gene. It was the gene-editing system CRISPR-Cas9. The team found the MyoAAVs correctly delivered the gene-editing system to muscle cells and also repaired dysfunctional copies of the dystrophin gene better than the CRISPR cargo carried by conventional AAVs. Importantly, the muscles of MyoAAV-treated animals also showed greater strength and function.

Next, the researchers teamed up with Alan Beggs, Boston Children’s Hospital, and found that MyoAAV was effective in treating mouse models of XLMTM. This is the very condition mentioned above, in which very high dose gene therapy with a current AAV vector has led to tragic outcomes. XLMTM mice normally die in 10 weeks. But, after receiving MyoAAV carrying a corrective gene, all six mice had a normal lifespan. By comparison, mice treated in the same way with traditional AAV lived only up to 21 weeks of age. What’s more, the researchers used MyoAAV at a dose 100 times lower than that currently used in clinical trials.

While further study is needed before this approach can be tested in people, MyoAAV was also used to successfully introduce therapeutic genes into human cells in the lab. This suggests that the early success in animals might hold up in people. The approach also has promise for developing AAVs with potential for targeting other organs, thereby possibly providing treatment for a wide range of genetic conditions.

The new findings are the result of a decade of work from Tabebordbar, the study’s first author. His tireless work is also personal. His father has a rare genetic muscle disease that has put him in a wheelchair. With this latest advance, the hope is that the next generation of promising gene therapies might soon make its way to the clinic to help Tabebordbar’s father and so many other people.

Reference:

[1] Directed evolution of a family of AAV capsid variants enabling potent muscle-directed gene delivery across species. Tabebordbar M, Lagerborg KA, Stanton A, King EM, Ye S, Tellez L, Krunnfusz A, Tavakoli S, Widrick JJ, Messemer KA, Troiano EC, Moghadaszadeh B, Peacker BL, Leacock KA, Horwitz N, Beggs AH, Wagers AJ, Sabeti PC. Cell. 2021 Sep 4:S0092-8674(21)01002-3.

Links:

Muscular Dystrophy Information Page (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke/NIH)

X-linked myotubular myopathy (Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center/National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences/NIH)

Somatic Cell Genome Editing (Common Fund/NIH)

Mohammadsharif Tabebordbar (Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard and Harvard University, Cambridge, MA)

Sabeti Lab (Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard and Harvard University)

NIH Support: Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; Common Fund

Experts Conclude Heritable Human Genome Editing Not Ready for Clinical Applications

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

We stand at a critical juncture in the history of science. CRISPR and other innovative genome editing systems have given researchers the ability to make very precise changes in the sequence, or spelling, of the human DNA instruction book. If these tools are used to make non-heritable edits in only relevant tissues, they hold enormous potential to treat or even cure a wide range of devastating disorders, such as sickle cell disease, inherited neurologic conditions, and muscular dystrophy. But profound safety, ethical, and philosophical concerns surround the use of such technologies to make heritable changes in the human genome—changes that can be passed on to offspring and have consequences for future generations of humankind.

Such concerns are not hypothetical. Two years ago, a researcher in China took it upon himself to cross this ethical red line and conduct heritable genome editing experiments in human embryos with the aim of protecting the resulting babies against HIV infection. The medical justification was indefensible, the safety issues were inadequately considered, and the consent process was woefully inadequate. In response to this epic scientific calamity, NIH supported a call by prominent scientists for an international moratorium on human heritable, or germline, genome editing for clinical purposes.

Following on the heels of this unprecedented ethical breach, the U.S. National Academy of Sciences, U.S. National Academy of Medicine, and the U.K. Royal Society convened an international commission, sponsored by NIH, to conduct a comprehensive review of the clinical use of human germline genome editing. The 18-member panel, which represented 10 nations and four continents, included experts in genome editing technology; human genetics and genomics; psychology; reproductive, pediatric, and adult medicine; regulatory science; bioethics; and international law. Earlier this month, this commission issued its consensus study report, entitled Heritable Human Genome Editing [1].

The commission was designed to bring together thought leaders around the globe to engage in serious discussions about this highly controversial use of genome-editing technology. Among the concerns expressed by many of us was that if heritable genome editing were allowed to proceed without careful deliberation, the enormous potential of non-heritable genome editing for prevention and treatment of disease could become overshadowed by justifiable public outrage, fear, and disgust.

I’m gratified to say that in its new report, the expert panel closely examined the scientific and ethical issues, and concluded that heritable human genome editing is too technologically unreliable and unsafe to risk testing it for any clinical application in humans at the present time. The report cited the potential for unintended off-target DNA edits, which could have harmful health effects, such as cancer, later in life. Also noted was the risk of producing so-called mosaic embryos, in which the edits occur in only a subset of an embryo’s cells. This would make it very difficult for researchers to predict the clinical effects of heritable genome editing in human beings.

Among the many questions that the panel was asked to consider was: should society ever decide that heritable gene editing might be acceptable, what would be a viable framework for scientists, clinicians, and regulatory authorities to assess the potential clinical applications?

In response to that question, the experts replied: heritable gene editing, if ever permitted, should be limited initially to serious diseases that result from the mutation of one or both copies of a single gene. The first uses of these technologies should proceed incrementally and with extreme caution. Their potential medical benefits and harms should also be carefully evaluated before proceeding.

The commission went on to stress that before such an option could be on the table, all other viable reproductive possibilities to produce an embryo without a disease-causing alteration must be exhausted. That would essentially limit heritable gene editing to the exceedingly rare instance in which both parents have two copies of a recessive, disease-causing gene variant. Or another quite rare instance in which one parent has two copies of an altered gene for a dominant genetic disorder, such as Huntington’s disease.

Recognizing how unusual both scenarios would be, the commission held out the possibility that some would-be parents with less serious conditions might qualify if 25 percent or less of their embryos are free of the disease-causing gene variant. A possible example is familial hypercholesterolemia (FH), in which people carrying a mutation in the LDL receptor gene have unusually high levels of cholesterol in their blood. If both members of a couple are affected, only 25 percent of their biological children would be unaffected. FH can lead to early heart disease and death, but drug treatment is available and improving all the time, which makes this a less compelling example. Also, the commission again indicated that such individuals would need to have already traveled down all other possible reproductive avenues before considering heritable gene editing.

A thorny ethical question that was only briefly addressed in the commission’s report is the overall value to be attached to a couple’s desire to have a biological child. That desire is certainly understandable, although other options, such an adoption or in vitro fertilization with donor sperm, are available. This seems like a classic example of the tension between individual desires and societal concerns. Is the drive for a biological child in very high-risk situations such a compelling circumstance that it justifies asking society to start down a path towards modifying human germline DNA?

The commission recommended establishing an international scientific advisory board to monitor the rapidly evolving state of genome editing technologies. The board would serve as an access point for scientists, legislators, and the public to access credible information to weigh the latest progress against the concerns associated with clinical use of heritable human genome editing.

The National Academies/Royal Society report has been sent along to the World Health Organization (WHO), where it will serve as a resource for its expert advisory committee on human genome editing. The WHO committee is currently developing recommendations for appropriate governance mechanisms for both heritable and non-heritable human genome editing research and their clinical uses. That panel could issue its guidance later this year, which is sure to continue this very important conversation.

Reference:

[1] Heritable Human Genome Editing, Report Summary, National Academy of Sciences, September 2020.

Links:

“Heritable Genome Editing Not Yet Ready to Be Tried Safely and Effectively in Humans,” National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine news release, Sep. 3, 2020.

International Commission on the Clinical Use of Human Germline Genome Editing (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine/Washington, D.C.)

Video: Report Release Webinar , International Commission on the Clinical Use of Human Germline Genome Editing (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine)

National Academy of Sciences (Washington, D.C.)

National Academy of Medicine (Washington, D.C.)

The Royal Society (London)

Nano-Sized Solution for Efficient and Versatile CRISPR Gene Editing

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: Guojun Chen and Amr Abdeen, University of Wisconsin-Madison

If used to make non-heritable genetic changes, CRISPR gene-editing technology holds tremendous promise for treating or curing a wide range of devastating disorders, including sickle cell disease, vision loss, and muscular dystrophy. Early efforts to deliver CRISPR-based therapies to affected tissues in a patient’s body typically have involved packing the gene-editing tools into viral vectors, which may cause unwanted immune reactions and other adverse effects.

Now, NIH-supported researchers have developed an alternative CRISPR delivery system: nanocapsules. Not only do these tiny, synthetic capsules appear to pose a lower risk of side effects, they can be precisely customized to deliver their gene-editing payloads to many different types of cells or tissues in the body, which can be extremely tough to do with a virus. Another advantage of these gene-editing nanocapsules is that they can be freeze-dried into a powder that’s easier than viral systems to transport, store, and administer at different doses.

In findings published in Nature Nanotechnology [1], researchers, led by Shaoqin Gong and Krishanu Saha, University of Wisconsin-Madison, developed the nanocapsules with specific design criteria in mind. They would need to be extremely small, about the size of a small virus, for easy entry into cells. Their surface would need to be adaptable for targeting different cell types. They also had to be highly stable in the bloodstream and yet easily degraded to release their contents once inside a cell.

After much hard work in the lab, they created their prototype. It features a thin polymer shell that’s easily decorated with peptides or other ingredients to target the nanocapsule to a predetermined cell type.

At just 25 nanometers in diameter, each nanocapsule still has room to carry cargo. That cargo includes a single CRISPR/Cas9 scissor-like enzyme for snipping DNA and a guide RNA that directs it to the right spot in the genome for editing.

In the bloodstream, the nanocapsules remain fully intact. But, once inside a cell, their polymer shells quickly disintegrate and release the gene-editing payload. How is this possible? The crosslinking molecules that hold the polymer together immediately degrade in the presence of another molecule, called glutathione, which is found at high levels inside cells.

The studies showed that human cells grown in the lab readily engulf and take the gene-editing nanocapsules into bubble-like endosomes. Their gene-editing contents are then released into the cytoplasm where they can begin making their way to a cell’s nucleus within a few hours.

Further study in lab dishes showed that nanocapsule delivery of CRISPR led to precise gene editing of up to about 80 percent of human cells with little sign of toxicity. The gene-editing nanocapsules also retained their potency even after they were freeze-dried and reconstituted.

But would the nanocapsules work in a living system? To find out, the researchers turned to mice, targeting their nanocapsules to skeletal muscle and tissue in the retina at the back of eye. Their studies showed that nanocapsules injected into muscle or the tight subretinal space led to efficient gene editing. In the eye, the nanocapsules worked especially well in editing retinal cells when they were decorated with a chemical ingredient known to bind an important retinal protein.

Based on their initial results, the researchers anticipate that their delivery system could reach most cells and tissues for virtually any gene-editing application. In fact, they are now exploring the potential of their nanocapsules for editing genes within brain tissue.

I’m also pleased to note that Gong and Saha’s team is part of a nationwide consortium on genome editing supported by NIH’s recently launched Somatic Cell Genome Editing program. This program is dedicated to translating breakthroughs in gene editing into treatments for as many genetic diseases as possible. So, we can all look forward to many more advances like this one.

Reference:

[1] A biodegradable nanocapsule delivers a Cas9 ribonucleoprotein complex for in vivo genome editing. Chen G, Abdeen AA, Wang Y, Shahi PK, Robertson S, Xie R, Suzuki M, Pattnaik BR, Saha K, Gong S. Nat Nanotechnol. 2019 Sep 9.

Links:

Somatic Cell Genome Editing (NIH)

Saha Lab (University of Wisconsin-Madison)

Shaoqin (Sarah) Gong (University of Wisconsin-Madison)

NIH Support: National Eye Institute; National Institute of General Medical Sciences; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Common Fund

Millions of Single-Cell Analyses Yield Most Comprehensive Human Cell Atlas Yet

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

There are 37 trillion or so cells in our bodies that work together to give us life. But it may surprise you that we still haven’t put a good number on how many distinct cell types there are within those trillions of cells.

That’s why in 2016, a team of researchers from around the globe launched a historic project called the Human Cell Atlas (HCA) consortium to identify and define the hundreds of presumed distinct cell types in our bodies. Knowing where each cell type resides in the body, and which genes each one turns on or off to create its own unique molecular identity, will revolutionize our studies of human biology and medicine across the board.

Since its launch, the HCA has progressed rapidly. In fact, it has already reached an important milestone with the recent publication in the journal Science of four studies that, together, comprise the first multi-tissue drafts of the human cell atlas. This draft, based on analyses of millions of cells, defines more than 500 different cell types in more than 30 human tissues. A second draft, with even finer definition, is already in the works.

Making the HCA possible are recent technological advances in RNA sequencing. RNA sequencing is a topic that’s been mentioned frequently on this blog in a range of research areas, from neuroscience to skin rashes. Researchers use it to detect and analyze all the messenger RNA (mRNA) molecules in a biological sample, in this case individual human cells from a wide range of tissues, organs, and individuals who voluntarily donated their tissues.

By quantifying these RNA messages, researchers can capture the thousands of genes that any given cell actively expresses at any one time. These precise gene expression profiles can be used to catalogue cells from throughout the body and understand the important similarities and differences among them.

In one of the published studies, funded in part by the NIH, a team co-led by Aviv Regev, a founding co-chair of the consortium at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, MA, established a framework for multi-tissue human cell atlases [1]. (Regev is now on leave from the Broad Institute and MIT and has recently moved to Genentech Research and Early Development, South San Francisco, CA.)

Among its many advances, Regev’s team optimized single-cell RNA sequencing for use on cell nuclei isolated from frozen tissue. This technological advance paved the way for single-cell analyses of the vast numbers of samples that are stored in research collections and freezers all around the world.

Using their new pipeline, Regev and team built an atlas including more than 200,000 single-cell RNA sequence profiles from eight tissue types collected from 16 individuals. These samples were archived earlier by NIH’s Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project. The team’s data revealed unexpected differences among cell types but surprising similarities, too.

For example, they found that genetic profiles seen in muscle cells were also present in connective tissue cells in the lungs. Using novel machine learning approaches to help make sense of their data, they’ve linked the cells in their atlases with thousands of genetic diseases and traits to identify cell types and genetic profiles that may contribute to a wide range of human conditions.

By cross-referencing 6,000 genes previously implicated in causing specific genetic disorders with their single-cell genetic profiles, they identified new cell types that may play unexpected roles. For instance, they found some non-muscle cells that may play a role in muscular dystrophy, a group of conditions in which muscles progressively weaken. More research will be needed to make sense of these fascinating, but vital, discoveries.

The team also compared genes that are more active in specific cell types to genes with previously identified links to more complex conditions. Again, their data surprised them. They identified new cell types that may play a role in conditions such as heart disease and inflammatory bowel disease.

Two of the other papers, one of which was funded in part by NIH, explored the immune system, especially the similarities and differences among immune cells that reside in specific tissues, such as scavenging macrophages [2,3] This is a critical area of study. Most of our understanding of the immune system comes from immune cells that circulate in the bloodstream, not these resident macrophages and other immune cells.

These immune cell atlases, which are still first drafts, already provide an invaluable resource toward designing new treatments to bolster immune responses, such as vaccines and anti-cancer treatments. They also may have implications for understanding what goes wrong in various autoimmune conditions.

Scientists have been working for more than 150 years to characterize the trillions of cells in our bodies. Thanks to this timely effort and its advances in describing and cataloguing cell types, we now have a much better foundation for understanding these fundamental units of the human body.

But the latest data are just the tip of the iceberg, with vast flows of biological information from throughout the human body surely to be released in the years ahead. And while consortium members continue making history, their hard work to date is freely available to the scientific community to explore critical biological questions with far-reaching implications for human health and disease.

References:

[1] Single-nucleus cross-tissue molecular reference maps toward understanding disease gene function. Eraslan G, Drokhlyansky E, Anand S, Fiskin E, Subramanian A, Segrè AV, Aguet F, Rozenblatt-Rosen O, Ardlie KG, Regev A, et al. Science. 2022 May 13;376(6594):eabl4290.

[2] Cross-tissue immune cell analysis reveals tissue-specific features in humans. Domínguez Conde C, Xu C, Jarvis LB, Rainbow DB, Farber DL, Saeb-Parsy K, Jones JL,Teichmann SA, et al. Science. 2022 May 13;376(6594):eabl5197.

[3] Mapping the developing human immune system across organs. Suo C, Dann E, Goh I, Jardine L, Marioni JC, Clatworthy MR, Haniffa M, Teichmann SA, et al. Science. 2022 May 12:eabo0510.

Links:

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) (National Human Genome Research Institute/NIH)

Studying Cells (National Institute of General Medical Sciences/NIH)

Regev Lab (Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, MA)

NIH Support: Common Fund; National Cancer Institute; National Human Genome Research Institute; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institute on Drug Abuse; National Institute of Mental Health; National Institute on Aging; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; National Eye Institute

DNA Base Editing May Treat Progeria, Study in Mice Shows

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

My good friend Sam Berns was born with a rare genetic condition that causes rapid premature aging. Though Sam passed away in his teens from complications of this condition, called Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome, he’s remembered today for his truly positive outlook on life. Sam expressed it, in part, by his willingness to make adjustments that allowed him, in his words, to put things that he always wanted to do in the “can do” category.

In this same spirit on behalf of the several hundred kids worldwide with progeria and their families, a research collaboration, including my NIH lab, has now achieved a key technical advance to move non-heritable gene editing another step closer to the “can do” category to treat progeria. As published in the journal Nature, our team took advantage of new gene-editing tools to correct for the first time a single genetic misspelling responsible for progeria in a mouse model, with dramatically beneficial effects [1, 2]. This work also has implications for correcting similar single-base typos that cause other inherited genetic disorders.

The outcome of this work is incredibly gratifying for me. In 2003, my NIH lab discovered the DNA mutation that causes progeria. One seemingly small glitch—swapping a “T” in place of a “C” in a gene called lamin A (LMNA)—leads to the production of a toxic protein now known as progerin. Without treatment, children with progeria develop normally intellectually but age at an exceedingly rapid pace, usually dying prematurely from heart attacks or strokes in their early teens.

The discovery raised the possibility that correcting this single-letter typo might one day help or even cure children with progeria. But back then, we lacked the needed tools to edit DNA safely and precisely. To be honest, I didn’t think that would be possible in my lifetime. Now, thanks to advances in basic genomic research, including work that led to the 2020 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, that’s changed. In fact, there’s been substantial progress toward using gene-editing technologies, such as the CRISPR editing system, for treating or even curing a wide range of devastating genetic conditions, such as sickle cell disease and muscular dystrophy

It turns out that the original CRISPR system, as powerful as it is, works better at knocking out genes than correcting them. That’s what makes some more recently developed DNA editing agents and approaches so important. One of them, which was developed by David R. Liu, Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, MA, and his lab members, is key to these latest findings on progeria, reported by a team including my lab in NIH’s National Human Genome Research Institute and Jonathan Brown, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN.

The relatively new gene-editing system moves beyond knock-outs to knock-ins [3,4]. Here’s how it works: Instead of cutting DNA as CRISPR does, base editors directly convert one DNA letter to another by enzymatically changing one DNA base to become a different base. The result is much like the find-and-replace function used to fix a typo in a word processor. What’s more, the gene editor does this without cutting the DNA.

Our three labs (Liu, Brown, and Collins) first teamed up with the Progeria Research Foundation, Peabody, MA, to obtain skin cells from kids with progeria. In lab studies, we found that base editors, targeted by an appropriate RNA guide, could successfully correct the LMNA gene in those connective tissue cells. The treatment converted the mutation back to the normal gene sequence in an impressive 90 percent of the cells.

But would it work in a living animal? To get the answer, we delivered a single injection of the DNA-editing apparatus into nearly a dozen mice either three or 14 days after birth, which corresponds in maturation level roughly to a 1-year-old or 5-year-old human. To ensure the findings in mice would be as relevant as possible to a future treatment for use in humans, we took advantage of a mouse model of progeria developed in my NIH lab in which the mice carry two copies of the human LMNA gene variant that causes the condition. Those mice develop nearly all of the features of the human illness

In the live mice, the base-editing treatment successfully edited in the gene’s healthy DNA sequence in 20 to 60 percent of cells across many organs. Many cell types maintained the corrected DNA sequence for at least six months—in fact, the most vulnerable cells in large arteries actually showed an almost 100 percent correction at 6 months, apparently because the corrected cells had compensated for the uncorrected cells that had died out. What’s more, the lifespan of the treated animals increased from seven to almost 18 months. In healthy mice, that’s approximately the beginning of old age.

This is the second notable advance in therapeutics for progeria in just three months. Last November, based on preclinical work from my lab and clinical trials conducted by the Progeria Research Foundation in Boston, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first treatment for the condition. It is a drug called Zokinvy, and works by reducing the accumulation of progerin [5]. With long-term treatment, the drug is capable of extending the life of kids with progeria by 2.5 years and sometimes more. But it is not a cure.

We are hopeful this gene editing work might eventually lead to a cure for progeria. But mice certainly aren’t humans, and there are still important steps that need to be completed before such a gene-editing treatment could be tried safely in people. In the meantime, base editors and other gene editing approaches keep getting better—with potential application to thousands of genetic diseases where we know the exact gene misspelling. As we look ahead to 2021, the dream envisioned all those years ago about fixing the tiny DNA typo responsible for progeria is now within our grasp and getting closer to landing in the “can do” category.

References:

[1] In vivo base editing rescues Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria Syndrome in mice. Koblan LW et al. Nature. 2021 Jan 6.

[2] Base editor repairs mutation found in the premature-ageing syndrome progeria. Vermeij WP, Hoeijmakers JHJ. Nature. 6 Jan 2021.

[3] Programmable editing of a target base in genomic DNA without double-stranded DNA cleavage. Komor AC, Kim YB, Packer MS, Zuris JA, Liu DR. Nature. 2016 May 19;533(7603):420-424.

[4] Programmable base editing of A•T to G•C in genomic DNA without DNA cleavage. Gaudelli NM, Komor AC, Rees HA, Packer MS, Badran AH, Bryson DI, Liu DR. Nature. 2017 Nov 23;551(7681):464-471.

[5] FDA approves first treatment for Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome and some progeroid laminopathies. Food and Drug Administration. 2020 Nov 20.

Links:

Progeria (Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center/NIH)

What are Genome Editing and CRISPR-Cas9? (National Library of Medicine/NIH)

Somatic Cell Genome Editing Program (Common Fund/NIH)

David R. Liu (Harvard University, Cambridge, MA)

Collins Group (National Human Genome Research Institute/NIH)

Jonathan Brown (Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN)

NIH Support: National Human Genome Research Institute; National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences; National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; National Institute of General Medical Sciences; Common Fund

Gene-Editing Advance Puts More Gene-Based Cures Within Reach

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

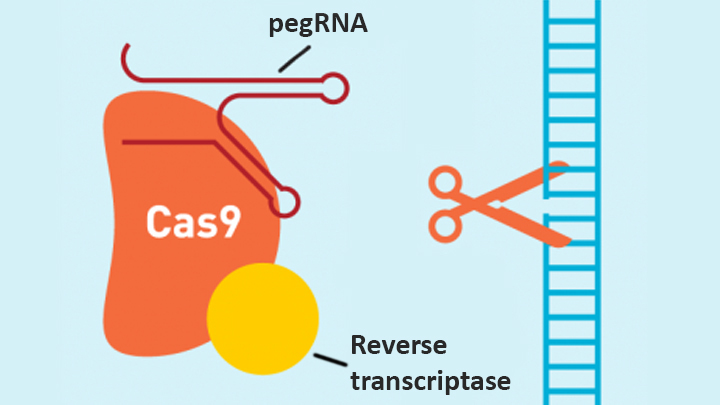

There’s been tremendous excitement recently about the potential of CRISPR and related gene-editing technologies for treating or even curing sickle cell disease (SCD), muscular dystrophy, HIV, and a wide range of other devastating conditions. Now comes word of another remarkable advance—called “prime editing”—that may bring us even closer to reaching that goal.

As groundbreaking as CRISPR/Cas9 has been for editing specific genes, the system has its limitations. The initial version is best suited for making a double-stranded break in DNA, followed by error-prone repair. The outcome is generally to knock out the target. That’s great if eliminating the target is the desired goal. But what if the goal is to fix a mutation by editing it back to the normal sequence?

The new prime editing system, which was described recently by NIH-funded researchers in the journal Nature, is revolutionary because it offers much greater control for making a wide range of precisely targeted edits to the DNA code, which consists of the four “letters” (actually chemical bases) A, C, G, and T [1].

Already, in tests involving human cells grown in the lab, the researchers have used prime editing to correct genetic mutations that cause two inherited diseases: SCD, a painful, life-threatening blood disorder, and Tay-Sachs disease, a fatal neurological disorder. What’s more, they say the versatility of their new gene-editing system means it can, in principle, correct about 89 percent of the more than 75,000 known genetic variants associated with human diseases.

In standard CRISPR, a scissor-like enzyme called Cas9 is used to cut all the way through both strands of the DNA molecule’s double helix. That usually results in the cell’s DNA repair apparatus inserting or deleting DNA letters at the site. As a result, CRISPR is extremely useful for disrupting genes and inserting or removing large DNA segments. However, it is difficult to use this system to make more subtle corrections to DNA, such as swapping a letter T for an A.

To expand the gene-editing toolbox, a research team led by David R. Liu, Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, MA, previously developed a class of editing agents called base editors [2,3]. Instead of cutting DNA, base editors directly convert one DNA letter to another. However, base editing has limitations, too. It works well for correcting four of the most common single letter mutations in DNA. But at least so far, base editors haven’t been able to make eight other single letter changes, or fix extra or missing DNA letters.

In contrast, the new prime editing system can precisely and efficiently swap any single letter of DNA for any other, and can make both deletions and insertions, at least up to a certain size. The system consists of a modified version of the Cas9 enzyme fused with another enzyme, called reverse transcriptase, and a specially engineered guide RNA, called pegRNA. The latter contains the desired gene edit and steers the needed editing apparatus to a specific site in a cell’s DNA.

Once at the site, the Cas9 nicks one strand of the double helix. Then, reverse transcriptase uses one DNA strand to “prime,” or initiate, the letter-by-letter transfer of new genetic information encoded in the pegRNA into the nicked spot, much like the search-and-replace function of word processing software. The process is then wrapped up when the prime editing system prompts the cell to remake the other DNA strand to match the new genetic information.

So far, in tests involving human cells grown in a lab dish, Liu and his colleagues have used prime editing to correct the most common mutation that causes SCD, converting a T to an A. They were also able to remove four DNA letters to correct the most common mutation underlying Tay-Sachs disease, a devastating condition that typically produces symptoms in children within the first year and leads to death by age four. The researchers also used their new system to insert new DNA segments up to 44 letters long and to remove segments at least 80 letters long.

Prime editing does have certain limitations. For example, 11 percent of known disease-causing variants result from changes in the number of gene copies, and it’s unclear if prime editing can insert or remove DNA that’s the size of full-length genes—which may contain up to 2.4 million letters.

It’s also worth noting that now-standard CRISPR editing and base editors have been tested far more thoroughly than prime editing in many different kinds of cells and animal models. These earlier editing technologies also may be more efficient for some purposes, so they will likely continue to play unique and useful roles in biomedicine.

As for prime editing, additional research is needed before we can consider launching human clinical trials. Among the areas that must be explored are this technology’s safety and efficacy in a wide range of cell types, and its potential for precisely and safely editing genes in targeted tissues within living animals and people.

Meanwhile, building on all these bold advances, efforts are already underway to accelerate the development of affordable, accessible gene-based cures for SCD and HIV on a global scale. Just last month, NIH and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation announced a collaboration that will invest at least $200 million over the next four years toward this goal. Last week, I had the chance to present this plan and discuss it with global health experts at the Grand Challenges meeting Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. The project is an unprecedented partnership designed to meet an unprecedented opportunity to address health conditions that once seemed out of reach but—as this new work helps to show—may now be within our grasp.

References:

[1] Search-and-replace genome editing without double-strand breaks or donor DNA. Anzalone AV, Randolph PB, Davis JR, Sousa AA, Koblan LW, Levy JM, Chen PJ, Wilson C, Newby GA, Raguram A, Liu DR. Nature. Online 2019 October 21. [Epub ahead of print]

[2] Programmable editing of a target base in genomic DNA without double-stranded DNA cleavage. Komor AC, Kim YB, Packer MS, Zuris JA, Liu DR. Nature. 2016 May 19;533(7603):420-424.

[3] Programmable base editing of A•T to G•C in genomic DNA without DNA cleavage. Gaudelli NM, Komor AC, Rees HA, Packer MS, Badran AH, Bryson DI, Liu DR. Nature. 2017 Nov 23;551(7681):464-471.

Links:

Tay-Sachs Disease (Genetics Home Reference/National Library of Medicine/NIH)

Sickle Cell Disease (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/NIH)

Cure Sickle Cell Initiative (NHLBI)

What are Genome Editing and CRISPR-Cas9? (National Library of Medicine/NIH)

Somatic Cell Genome Editing Program (Common Fund/NIH)

David R. Liu (Harvard, Cambridge, MA)

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; National Human Genome Research Institute; National Institute for General Medical Sciences; National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering; National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences

Next Page