brown fat

The People’s Picks for Best Posts

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

It’s 2021—Happy New Year! Time sure flies in the blogosphere. It seems like just yesterday that I started the NIH Director’s Blog to highlight recent advances in biology and medicine, many supported by NIH. Yet it turns out that more than eight years have passed since this blog got rolling and we are fast approaching my 1,000th post!

I’m pleased that millions of you have clicked on these posts to check out some very cool science and learn more about NIH and its mission. Thanks to the wonders of social media software, we’ve been able to tally up those views to determine each year’s most-popular post. So, I thought it would be fun to ring in the New Year by looking back at a few of your favorites, sort of a geeky version of a top 10 countdown or the People’s Choice Awards. It was interesting to see what topics generated the greatest interest. Spoiler alert: diet and exercise seemed to matter a lot! So, without further ado, I present the winners:

2013: Fighting Obesity: New Hopes from Brown Fat. Brown fat, one of several types of fat made by our bodies, was long thought to produce body heat rather than store energy. But Shingo Kajimura and his team at the University of California, San Francisco, showed in a study published in the journal Nature, that brown fat does more than that. They discovered a gene that acts as a molecular switch to produce brown fat, then linked mutations in this gene to obesity in humans.

What was also nice about this blog post is that it appeared just after Kajimura had started his own lab. In fact, this was one of the lab’s first publications. One of my goals when starting the blog was to feature young researchers, and this work certainly deserved the attention it got from blog readers. Since highlighting this work, research on brown fat has continued to progress, with new evidence in humans suggesting that brown fat is an effective target to improve glucose homeostasis.

2014: In Memory of Sam Berns. I wrote this blog post as a tribute to someone who will always be very near and dear to me. Sam Berns was born with Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome, one of the rarest of rare diseases. After receiving the sad news that this brave young man had passed away, I wrote: “Sam may have only lived 17 years, but in his short life he taught the rest of us a lot about how to live.”

Affecting approximately 400 people worldwide, progeria causes premature aging. Without treatment, children with progeria, who have completely normal intellectual development, die of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, on average in their early teens.

From interactions with Sam and his parents in the early 2000s, I started to study progeria in my NIH lab, eventually identifying the gene responsible for the disorder. My group and others have learned a lot since then. So, it was heartening last November when the Food and Drug Administration approved the first treatment for progeria. It’s an oral medication called Zokinvy (lonafarnib) that helps prevent the buildup of defective protein that has deadly consequences. In clinical trials, the drug increased the average survival time of those with progeria by more than two years. It’s a good beginning, but we have much more work to do in the memory of Sam and to help others with progeria. Watch for more about new developments in applying gene editing to progeria in the next few days.

2015: Cytotoxic T Cells on Patrol. Readers absolutely loved this post. When the American Society of Cell Biology held its first annual video competition, called CellDance, my blog featured some of the winners. Among them was this captivating video from Alex Ritter, then working with cell biologist Jennifer Lippincott-Schwartz of NIH’s Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The video stars a roving, specialized component of our immune system called cytotoxic T cells. Their job is to seek out and destroy any foreign or detrimental cells. Here, these T cells literally convince a problem cell to commit suicide, a process that takes about 10 minutes from detection to death.

These cytotoxic T cells are critical players in cancer immunotherapy, in which a patient’s own immune system is enlisted to control and, in some cases, even cure the cancer. Cancer immunotherapy remains a promising area of research that continues to progress, with a lot of attention now being focused on developing immunotherapies for common, solid tumors like breast cancer. Ritter is currently completing a postdoctoral fellowship in the laboratory of Ira Mellman, Genentech, South San Francisco. His focus has shifted to how cancer cells protect themselves from T cells. And video buffs—get this—Ritter says he’s now created even cooler videos that than the one in this post.

2016: Exercise Releases Brain-Healthy Protein. The research literature is pretty clear: exercise is good for the brain. In this very popular post, researchers led by Hyo Youl Moon and Henriette van Praag of NIH’s National Institute on Aging identified a protein secreted by skeletal muscle cells to help explore the muscle-brain connection. In a study in Cell Metabolism, Moon and his team showed that this protein called cathepsin B makes its way into the brain and after a good workout influences the development of new neural connections. This post is also memorable to me for the photo collage that accompanied the original post. Why? If you look closely at the bottom right, you’ll see me exercising—part of my regular morning routine!

2017: Muscle Enzyme Explains Weight Gain in Middle Age. The struggle to maintain a healthy weight is a lifelong challenge for many of us. While several risk factors for weight gain, such as counting calories, are within our control, there’s a major one that isn’t: age. Jay Chung, a researcher with NIH’s National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, and his team discovered that the normal aging process causes levels of an enzyme called DNA-PK to rise in animals as they approach middle age. While the enzyme is known for its role in DNA repair, their studies showed it also slows down metabolism, making it more difficult to burn fat.

Since publishing this paper in Cell Metabolism, Chung has been busy trying to understand how aging increases the activity of DNA-PK and its ability to suppress renewal of the cell’s energy-producing mitochondria. Without renewal of damaged mitochondria, excess oxidants accumulate in cells that then activate DNA-PK, which contributed to the damage in the first place. Chung calls it a “vicious cycle” of aging and one that we’ll be learning more about in the future.

2018: Has an Alternative to Table Sugar Contributed to the C. Diff. Epidemic? This impressive bit of microbial detective work had blog readers clicking and commenting for several weeks. So, it’s no surprise that it was the runaway People’s Choice of 2018.

Clostridium difficile (C. diff) is a common bacterium that lives harmlessly in the gut of most people. But taking antibiotics can upset the normal balance of healthy gut microbes, allowing C. diff. to multiply and produce toxins that cause inflammation and diarrhea.

In the 2000s, C. diff. infections became far more serious and common in American hospitals, and Robert Britton, a researcher at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, wanted to know why. He and his team discovered that two subtypes of C. diff have adapted to feed on the sugar trehalose, which was approved as a food additive in the United States during the early 2000s. The team’s findings, published in the journal Nature, suggested that hospitals and nursing homes battling C. diff. outbreaks may want to take a closer look at the effect of trehalose in the diet of their patients.

2019: Study Finds No Benefit for Dietary Supplements. This post that was another one that sparked a firestorm of comments from readers. A team of NIH-supported researchers, led by Fang Fang Zhang, Tufts University, Boston, found that people who reported taking dietary supplements had about the same risk of dying as those who got their nutrients through food. What’s more, the mortality benefits associated with adequate intake of vitamin A, vitamin K, magnesium, zinc, and copper were limited to amounts that are available from food consumption. The researchers based their conclusion on an analysis of the well-known National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) between 1999-2000 and 2009-2010 survey data. The team, which reported its data in the Annals of Internal Medicine, also uncovered some evidence suggesting that certain supplements might even be harmful to health when taken in excess.

2020: Genes, Blood Type Tied to Risk of Severe COVID-19. Typically, my blog focuses on research involving many different diseases. That changed in 2020 due to the emergence of a formidable public health challenge: the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Since last March, the blog has featured 85 posts on COVID-19, covering all aspects of the research response and attracting more visitors than ever. And which post got the most views? It was one that highlighted a study, published last June in the New England Journal of Medicine, that suggested the clues to people’s variable responses to COVID-19 may be found in our genes and our blood types.

The researchers found that gene variants in two regions of the human genome are associated with severe COVID-19 and correspondingly carry a greater risk of COVID-19-related death. The two stretches of DNA implicated as harboring risks for severe COVID-19 are known to carry some intriguing genes, including one that determines blood type and others that play various roles in the immune system.

In fact, the findings suggest that people with blood type A face a 50 percent greater risk of needing oxygen support or a ventilator should they become infected with the novel coronavirus. In contrast, people with blood type O appear to have about a 50 percent reduced risk of severe COVID-19.

That’s it for the blog’s year-by-year Top Hits. But wait! I’d also like to give shout outs to the People’s Choice winners in two other important categories—history and cool science images.

Top History Post: HeLa Cells: A New Chapter in An Enduring Story. Published in August 2013, this post remains one of the blog’s greatest hits with readers. The post highlights science’s use of cancer cells taken in the 1950s from a young Black woman named Henrietta Lacks. These “HeLa” cells had an amazing property not seen before: they could be grown continuously in laboratory conditions. The “new chapter” featured in this post is an agreement with the Lacks family that gives researchers access to the HeLa genome data, while still protecting the family’s privacy and recognizing their enormous contribution to medical research. And the acknowledgments rightfully keep coming from those who know this remarkable story, which has been chronicled in both book and film. Recently, the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives passed the Henrietta Lacks Enhancing Cancer Research Act to honor her extraordinary life and examine access to government-funded cancer clinical trials for traditionally underrepresented groups.

Top Snapshots of Life: A Close-up of COVID-19 in Lung Cells. My blog posts come in several categories. One that you may have noticed is “Snapshots of Life,” which provides a showcase for cool images that appear in scientific journals and often dominate Science as Art contests. My blog has published dozens of these eye-catching images, representing a broad spectrum of the biomedical sciences. But the blog People’s Choice goes to a very recent addition that reveals exactly what happens to cells in the human airway when they are infected with the coronavirus responsible for COVID-19. This vivid image, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, comes from the lab of pediatric pulmonologist Camille Ehre, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. This image squeezed in just ahead of another highly popular post from Steve Ramirez, Boston University, in 2019 that showed “What a Memory Looks Like.”

As we look ahead to 2021, I want to thank each of my blog’s readers for your views and comments over the last eight years. I love to hear from you, so keep on clicking! I’m confident that 2021 will generate a lot more amazing and bloggable science, including even more progress toward ending the COVID-19 pandemic that made our past year so very challenging.

Fighting Obesity: New Hopes From Brown Fat

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

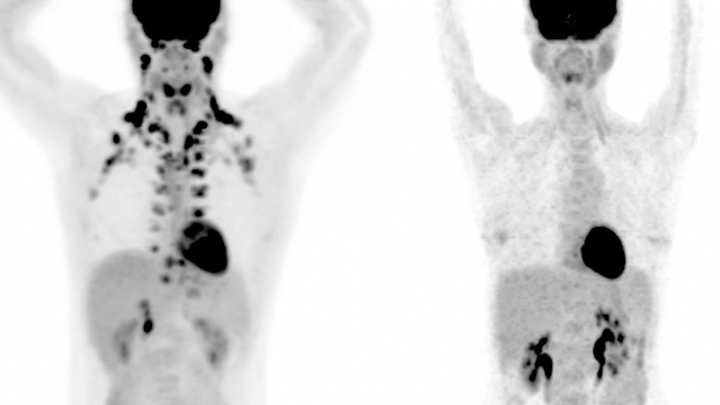

Illustration: John MacNeill, based on patient imaging software designed by Ilan Tal. Copyright 2011 Joslin Diabetes Center

If you want to lose weight, then you actually want more fat, not less. But you need the right kind: brown fat. This special type of fatty tissue burns calories, puts out heat like a furnace, and helps to keep you trim. White fat, on the other hand, stores extra calories and makes you, well, fat. Wouldn’t it be nice if we could instruct our bodies to make more brown fat, and less white fat? Well, NIH-funded researchers have just taken another step in that direction [1].

Brown Fat, White Fat, Good Fat, Bad Fat

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

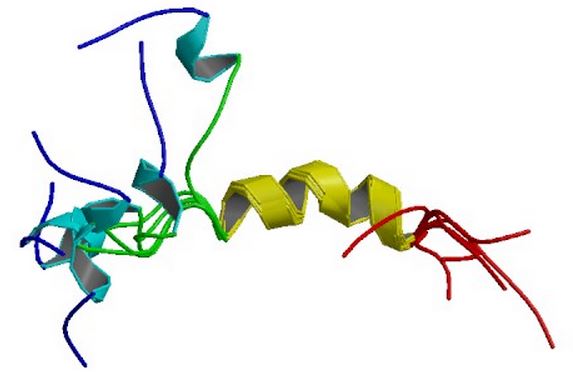

Credit: Patrick Seale, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine

Fat has been villainized; but all fat was not created equal. Our two main types of fat—brown and white—play different roles. Now, two teams of NIH-funded researchers have enriched our understanding of adipose tissue. The first team discovered the genetic switch that triggers the development of brown fat [1], and the second figured out how the body can recruit white fat and transform it into brown [2].

Why would we want to change white fat into brown? White fat stores energy as large fat droplets, while brown fat has much smaller droplets and is specialized to burn them, yielding heat. Brown fat cells are packed with energy generating powerhouses called mitochondria that contain iron—which gives them their brown color. Infants are born with rich stores of brown fat (about 5% of total body mass) on the upper spine and shoulders to keep them warm. It used to be thought that brown fat disappeared by adulthood—but it turns out we harbor small reserves in our shoulders and neck.