glioblastoma

Rice-Sized Device Tests Brain Tumor’s Drug Responses During Surgery

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

Scientists have made remarkable progress in understanding the underlying changes that make cancer grow and have applied this knowledge to develop and guide targeted treatment approaches to vastly improve outcomes for people with many cancer types. And yet treatment progress for people with brain tumors known as gliomas—including the most aggressive glioblastomas—has remained slow. One reason is that doctors lack tests that reliably predict which among many therapeutic options will work best for a given tumor.

Now an NIH-funded team has developed a miniature device with the potential to change this for the approximately 25,000 people diagnosed with brain cancers in the U.S. each year [1]. When implanted into cancerous brain tissue during surgery, the rice-sized drug-releasing device can simultaneously conduct experiments to measure a tumor’s response to more than a dozen drugs or drug combinations. What’s more, a small clinical trial reported in Science Translational Medicine offers the first evidence in people with gliomas that these devices can safely offer unprecedented insight into tumor-specific drug responses [2].

These latest findings come from a Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, team led by Pierpaolo Peruzzi and Oliver Jonas. They recognized that drug-screening studies conducted in cells or tissue samples in the lab too often failed to match what happens in people with gliomas undergoing cancer treatment. Wide variation within individual brain tumors also makes it hard to predict a tumor’s likely response to various treatment options.

It led them to an intriguing idea: Why not test various therapeutic options in each patient’s tumor? To do it, they developed a device, about six millimeters long, that can be inserted into a brain tumor during surgery to deliver tiny doses of up to 20 drugs. Doctors can then remove and examine the drug-exposed cancerous tissue in the laboratory to determine each treatment’s effects. The data can then be used to guide subsequent treatment decisions, according to the researchers.

In the current study, the researchers tested their device on six study volunteers undergoing brain surgery to remove a glioma tumor. For each volunteer, the device was implanted into the tumor and remained in place for about two to three hours while surgeons worked to remove most of the tumor. Next, the device was taken out along with the last piece of a tumor at the end of the surgery for further study of drug responses.

Importantly, none of the study participants experienced any adverse effects from the device. Using the devices, the researchers collected valuable data, including how a tumor’s response changed with varying drug concentrations or how each treatment led to molecular changes in the cancerous cells.

More research is needed to better understand how use of such a device might change treatment and patient outcomes in the longer term. The researchers note that it would take more than a couple of hours to determine how treatments produce less immediate changes, such as immune responses. As such, they’re now conducting a follow-up trial to test a possible two-stage procedure, in which their device is inserted first using minimally invasive surgery 72 hours prior to a planned surgery, allowing longer exposure of tumor tissue to drugs prior to a tumor’s surgical removal.

Many questions remain as they continue to optimize this approach. However, it’s clear that such a device gives new meaning to personalized cancer treatment, with great potential to improve outcomes for people living with hard-to-treat gliomas.

References:

[1] National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Cancer Stat Facts: Brain and Other Nervous System Cancer.

[2] Peruzzi P et al. Intratumoral drug-releasing microdevices allow in situ high-throughput pharmaco phenotyping in patients with gliomas. Science Translational Medicine DOI: 10.1126/scitranslmed.adi0069 (2023).

Links:

Brain Tumors – Patient Version (National Cancer Institute/NIH)

Pierpaolo Peruzzi (Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA)

Jonas Lab (Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA)

NIH Support: National Cancer Institute, National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

Basic Researchers Discover Possible Target for Treating Brain Cancer

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

Over the years, cancer researchers have uncovered many of the tricks that tumors use to fuel their growth and evade detection by the body’s immune system. More tricks await discovery, and finding them will be key in learning to target the right treatments to the right cancers.

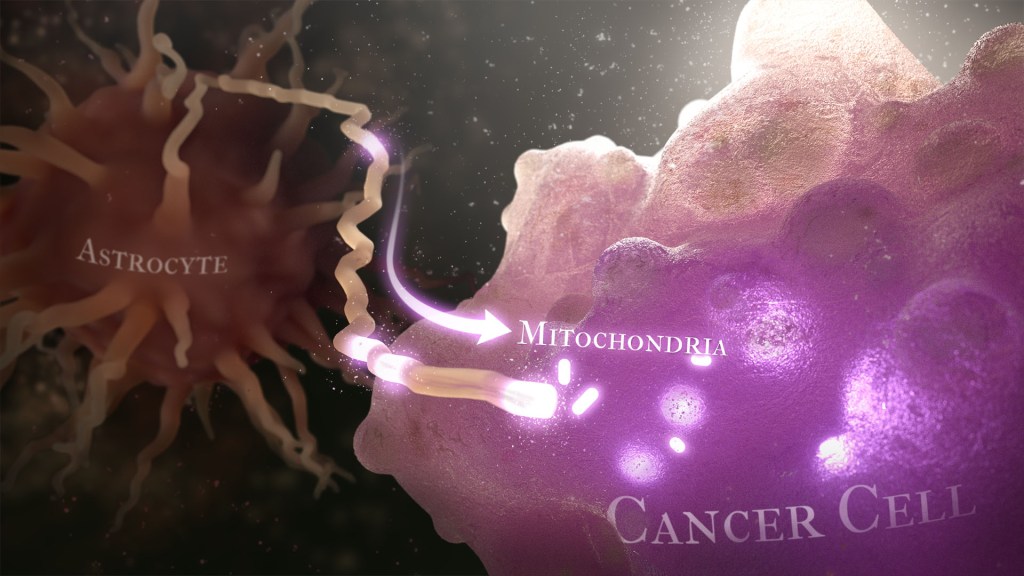

Recently, a team of researchers demonstrated in lab studies a surprising trick pulled off by cells from a common form of brain cancer called glioblastoma. The researchers found that glioblastoma cells steal mitochondria, the power plants of our cells, from other cells in the central nervous system [1].

Why would cancer cells do this? How do they pull it off? The researchers don’t have all the answers yet. But glioblastoma arises from abnormal astrocytes, a particular type of the glial cell, a common cell in the brain and spinal cord. It seems from their initial work that stealing mitochondria from neighboring normal cells help these transformed glioblastoma cells to ramp up their growth. This trick might also help to explain why glioblastoma is one of the most aggressive forms of primary brain cancer, with limited treatment options.

In the new study, published in the journal Nature Cancer, a team co-led by Justin Lathia, Lerner Research Institute, Cleveland Clinic, OH, and Hrvoje Miletic, University of Bergen, Norway, had noticed some earlier studies suggesting that glioblastoma cells might steal mitochondria. They wanted to take a closer look.

This very notion highlights an emerging and much more dynamic view of mitochondria. Scientists used to think that mitochondria—which can number in the thousands within a single cell—generally just stayed put. But recent research has established that mitochondria can move around within a cell. They sometimes also get passed from one cell to another.

It also turns out that the intercellular movement of mitochondria has many implications for health. For instance, the transfer of mitochondria helps to rescue damaged tissues in the central nervous system, heart, and respiratory system. But, in other circumstances, this process may possibly come to the rescue of cancer cells.

While Lathia, Miletic, and team knew that mitochondrial transfer was possible, they didn’t know how relevant or dangerous it might be in brain cancers. To find out, they studied mice implanted with glioblastoma tumors from other mice or people with glioblastoma. This mouse model also had been modified to allow the researchers to trace the movement of mitochondria.

Their studies show that healthy cells often transfer some of their mitochondria to glioblastoma cells. They also determined that those mitochondria often came from healthy astrocytes, a process that had been seen before in the recovery from a stroke.

But the transfer process isn’t easy. It requires that a cell expend a lot of energy to form actin filaments that contract to pull the mitochondria along. They also found that the process depends on growth-associated protein 43 (GAP43), suggesting that future treatments aimed at this protein might help to thwart the process.

Their studies also show that, after acquiring extra mitochondria, glioblastoma cells shift into higher gear. The cancerous cells begin burning more energy as their metabolic pathways show increased activity. These changes allow for more rapid and aggressive growth. Overall, the findings show that this interaction between healthy and cancerous cells may partly explain why glioblastomas are so often hard to beat.

While more study is needed to confirm the role of this process in people with glioblastoma, the findings are an important reminder that treatment advances in oncology may come not only from study of the cancer itself but also by carefully considering the larger context and environments in which tumors grow. The hope is that these intriguing new findings will one day lead to new treatment options for the approximately 13,000 people in the U.S. alone who are diagnosed with glioblastoma each year [2].

References:

[1] GAP43-dependent mitochondria transfer from astrocytes enhances glioblastoma tumorigenicity. Watson DC, Bayik D, Storevik S, Moreino SS, Hjelmeland AB, Hossain JA, Miletic H, Lathia JD et al. Nat Cancer. 2023 May 11. [Published online ahead of print.]

[2] CBTRUS statistical report: Primary brain and other central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2011-2015. Ostrom QT, Gittleman H, Truitt G, Boscia A, Kruchko C, Barnholtz-Sloan JS. 2018 Oct 1, Neuro Oncol., p. 20(suppl_4):iv1-iv86.

Links:

Glioblastoma (National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences/NIH)

Brain Tumors (National Cancer Institute/NIH)

Justin Lathia Lab (Cleveland Clinic, OH)

Hrvoje Miletic (University of Bergen, Norway)

NIH Support: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences; National Cancer Institute; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

Fighting Cancer with Next-Gen Cell Engineering

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Researchers continue to make progress with cancer immunotherapy, a type of treatment that harnesses the body’s own immune cells to attack cancer. But Kole Roybal wants to help move the field further ahead by engineering patients’ immune cells to detect an even broader range of cancers and then launch customized attacks against them.

With an eye toward developing the next generation of cell-based immunotherapies, this synthetic biologist at University of California, San Francisco, has already innovatively hacked into how certain cells communicate with each other. Now, he and his research team are using a 2018 NIH Director’s New Innovator Award to build upon that progress.

Roybal’s initial inspiration is CAR-T therapy, one of the most advanced immunotherapies to date. In CAR-T therapy, some of a cancer patient’s key immune cells, called T cells, are removed and engineered in a way that they begin to produce new surface proteins called chimeric antigen receptors (CARs). Those receptors allow the cells to recognize and attack cancer cells more effectively. After expanding the number of these engineered T cells in the lab, doctors infuse them back into patients to enhance their immune systems’s ability to seek-and-destroy their cancer.

As helpful as this approach has been for some people with leukemia, lymphoma, and certain other cancers, it has its limitations. For one, CAR-T therapy relies solely on a T cell’s natural activation program, which can be toxic to patients if the immune cells damage healthy tissues. In other patients, the response simply isn’t strong enough to eradicate a cancer.

Roybal realized that redirecting T cells to attack a broader range of cancers would take more than simply engineering the receptors to bind to cancer cells. It also would require sculpting novel immune cell responses once those receptors were triggered.

Roybal found a solution in a new class of lab-made receptors known as Synthetic Notch, or SynNotch, that he and his colleagues have been developing over the last several years [1, 2]. Notch protein receptors play an essential role in developmental pathways and cell-to-cell communication across a wide range of animal species. What Roybal and his colleagues found especially intriguing is the protein receptors’ mode of action is remarkably direct.

When a protein binds the Notch receptor, a portion of the receptor breaks off and heads for the cell nucleus, where it acts as a switch to turn on other genes. They realized that engineering a cancer patient’s immune cells with synthetic SynNotch receptors could offer extraordinary flexibility in customized sensing and response behaviors. What’s more, the receptors could be tailored to respond to a number of user-specified cues outside of a cell.

In his NIH-supported work, Roybal will devise various versions of SynNotch-engineered cells targeting solid tumors that have proven difficult to treat with current cell therapies. He reports that they are currently developing the tools to engineer cells to sense a broad spectrum of cancers, including melanoma, glioblastoma, and pancreatic cancer.

They’re also engineering cells equipped to respond to a tumor by producing a range of immune factors, including antibodies known to unleash the immune system against cancer. He says he’ll also work on adding engineered SynNotch molecules to other immune cell types, not just T cells.

Given the versatility of the approach, Roybal doesn’t plan to stop there. He’s also interested in regenerative medicine and in engineering therapeutic cells to treat autoimmune conditions. I’m looking forward to see just how far these and other next-gen cell therapies will take us.

References:

[1] Engineering Customized Cell Sensing and Response Behaviors Using Synthetic Notch Receptors. Morsut L, Roybal KT, Xiong X, Gordley RM, Coyle SM, Thomson M, Lim WA. Cell. 2016 Feb 11;164(4):780-91.

[2] Engineering T Cells with Customized Therapeutic Response Programs Using Synthetic Notch Receptors. Roybal KT, Williams JZ, Morsut L, Rupp LJ, Kolinko I, Choe JH, Walker WJ, McNally KA, Lim WA. Cell. 2016 Oct 6;167(2):419-432.e16.

Links:

Car-T Cells: Engineering Patients’ Immune Cells to Treat Cancers (National Cancer Institute/NIH)

Synthetic Biology for Technology Development (National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering/NIH)

Roybal Lab (University of California, San Francisco)

Roybal Project Information (NIH RePORTER)

NIH Support: Common Fund; National Cancer Institute

Creative Minds: A New Way to Look at Cancer

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Inside our cells, strands of DNA wrap around spool-like histone proteins to form a DNA-histone complex called chromatin. Bradley Bernstein, a pathologist at Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard University, and Broad Institute, has always been fascinated by this process. What interests him is the fact that an approximately 6-foot-long strand of DNA can be folded and packed into orderly chromatin structures inside a cell nucleus that’s just 0.0002 inch wide.

Bernstein’s fascination with DNA packaging led to the recent major discovery that, when chromatin misfolds in brain cells, it can activate a gene associated with the cancer glioma [1]. This suggested a new cancer-causing mechanism that does not require specific DNA mutations. Now, with a 2016 NIH Director’s Pioneer Award, Bernstein is taking a closer look at how misfolded and unstable chromatin can drive tumor formation, and what that means for treating cancer.

Precision Oncology: Epigenetic Patterns Predict Glioblastoma Outcomes

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: Oncologists review a close-up image of a brain tumor (green dot).

Credit: National Cancer Institute

Scientists have spent much time and energy mapping the many DNA misspellings that can transform healthy cells into cancerous ones. But recently it has become increasingly clear that changes to the DNA sequence itself are not the only culprits. Cancer can also be driven by epigenetic changes to DNA—modifications to chemical marks on the genome don’t alter the sequence of the DNA molecule, but act to influence gene activity. A prime example of this can been seen in glioblastoma, a rare and deadly form of brain cancer that strikes about 12,000 Americans each year.

In fact, an NIH-funded research team recently published in Nature Communications the most complete portrait to date of the epigenetic patterns characteristic of the glioblastoma genome [1]. Among their findings were patterns associated with how long patients survived after the cancer was detected. While far more research is needed, the findings highlight the potential of epigenetic information to help doctors devise more precise ways of diagnosing, treating, and perhaps even preventing glioblastoma and many other forms of cancer.