actin filaments

Basic Researchers Discover Possible Target for Treating Brain Cancer

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

Over the years, cancer researchers have uncovered many of the tricks that tumors use to fuel their growth and evade detection by the body’s immune system. More tricks await discovery, and finding them will be key in learning to target the right treatments to the right cancers.

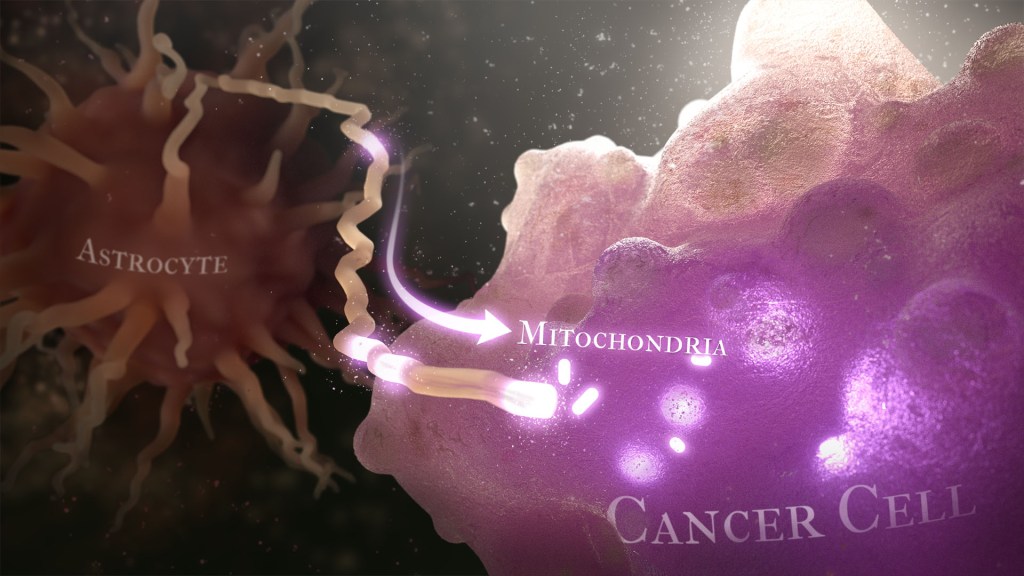

Recently, a team of researchers demonstrated in lab studies a surprising trick pulled off by cells from a common form of brain cancer called glioblastoma. The researchers found that glioblastoma cells steal mitochondria, the power plants of our cells, from other cells in the central nervous system [1].

Why would cancer cells do this? How do they pull it off? The researchers don’t have all the answers yet. But glioblastoma arises from abnormal astrocytes, a particular type of the glial cell, a common cell in the brain and spinal cord. It seems from their initial work that stealing mitochondria from neighboring normal cells help these transformed glioblastoma cells to ramp up their growth. This trick might also help to explain why glioblastoma is one of the most aggressive forms of primary brain cancer, with limited treatment options.

In the new study, published in the journal Nature Cancer, a team co-led by Justin Lathia, Lerner Research Institute, Cleveland Clinic, OH, and Hrvoje Miletic, University of Bergen, Norway, had noticed some earlier studies suggesting that glioblastoma cells might steal mitochondria. They wanted to take a closer look.

This very notion highlights an emerging and much more dynamic view of mitochondria. Scientists used to think that mitochondria—which can number in the thousands within a single cell—generally just stayed put. But recent research has established that mitochondria can move around within a cell. They sometimes also get passed from one cell to another.

It also turns out that the intercellular movement of mitochondria has many implications for health. For instance, the transfer of mitochondria helps to rescue damaged tissues in the central nervous system, heart, and respiratory system. But, in other circumstances, this process may possibly come to the rescue of cancer cells.

While Lathia, Miletic, and team knew that mitochondrial transfer was possible, they didn’t know how relevant or dangerous it might be in brain cancers. To find out, they studied mice implanted with glioblastoma tumors from other mice or people with glioblastoma. This mouse model also had been modified to allow the researchers to trace the movement of mitochondria.

Their studies show that healthy cells often transfer some of their mitochondria to glioblastoma cells. They also determined that those mitochondria often came from healthy astrocytes, a process that had been seen before in the recovery from a stroke.

But the transfer process isn’t easy. It requires that a cell expend a lot of energy to form actin filaments that contract to pull the mitochondria along. They also found that the process depends on growth-associated protein 43 (GAP43), suggesting that future treatments aimed at this protein might help to thwart the process.

Their studies also show that, after acquiring extra mitochondria, glioblastoma cells shift into higher gear. The cancerous cells begin burning more energy as their metabolic pathways show increased activity. These changes allow for more rapid and aggressive growth. Overall, the findings show that this interaction between healthy and cancerous cells may partly explain why glioblastomas are so often hard to beat.

While more study is needed to confirm the role of this process in people with glioblastoma, the findings are an important reminder that treatment advances in oncology may come not only from study of the cancer itself but also by carefully considering the larger context and environments in which tumors grow. The hope is that these intriguing new findings will one day lead to new treatment options for the approximately 13,000 people in the U.S. alone who are diagnosed with glioblastoma each year [2].

References:

[1] GAP43-dependent mitochondria transfer from astrocytes enhances glioblastoma tumorigenicity. Watson DC, Bayik D, Storevik S, Moreino SS, Hjelmeland AB, Hossain JA, Miletic H, Lathia JD et al. Nat Cancer. 2023 May 11. [Published online ahead of print.]

[2] CBTRUS statistical report: Primary brain and other central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2011-2015. Ostrom QT, Gittleman H, Truitt G, Boscia A, Kruchko C, Barnholtz-Sloan JS. 2018 Oct 1, Neuro Oncol., p. 20(suppl_4):iv1-iv86.

Links:

Glioblastoma (National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences/NIH)

Brain Tumors (National Cancer Institute/NIH)

Justin Lathia Lab (Cleveland Clinic, OH)

Hrvoje Miletic (University of Bergen, Norway)

NIH Support: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences; National Cancer Institute; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

The Actin Superhighway

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: Andrew Lombardo and David Warshaw, University of Vermont, Burlington

What looks like a traffic grid filled with roundabouts is nothing of the sort: It’s actually a peek inside a tiny microchamber that models a complex system operating in many of our cells. The system is a molecular transportation network made of the protein actin, and researchers have reconstructed it in the lab to study its rules of the road and, when things go wrong, how it can lead to molecular traffic accidents.

This 3D super-resolution image shows the model’s silicone beads (circles) positioned in a tiny microfluidic-chamber. Suspended from the beads are actin filaments that form some of the main cytoskeletal roadways in our cells. Interestingly, a single dye creates the photo’s beautiful colors, which arise from the different vertical dimensions of a microscopic image: 300 nanometers below the focus (red), at focus (green), and 300 nanometers above the focus (blue). When a component spans multiple dimensions—such as the spherical beads—all the colors of the rainbow are visible. The technique is called 3D stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy, or STORM [1].

The Beauty of Recycling

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Novel proteasome regulation image by Sigi Benjamin-Hong, Strang Laboratory of Apoptosis and Cancer Biology.

All cells recycle. Here, we see actin filaments (red) direct unwanted (malformed, damaged, or toxic) proteins to proteasomes (green). In these barrel-shaped compartments, proteins are chopped up into their basic building blocks, called amino acids, and recycled to make new healthy proteins.