memory

New Study Points to Targetable Protective Factor in Alzheimer’s Disease

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

If you’ve spent time with individuals affected with Alzheimer’s disease (AD), you might have noticed that some people lose their memory and other cognitive skills more slowly than others. Why is that? New findings indicate that at least part of the answer may lie in differences in their immune responses.

Researchers have now found that slower loss of cognitive skills in people with AD correlates with higher levels of a protein that helps immune cells clear plaque-like cellular debris from the brain [1]. The efficiency of this clean-up process in the brain can be measured via fragments of the protein that shed into the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). This suggests that the protein, called TREM2, and the immune system as a whole, may be promising targets to help fight Alzheimer’s disease.

The findings come from an international research team led by Michael Ewers, Institute for Stroke and Dementia Research, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Germany, and Christian Haass, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Germany and German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases. The researchers got interested in TREM2 following the discovery several years ago that people carrying rare genetic variants for the protein were two to three times more likely to develop AD late in life.

Not much was previously known about TREM2, so this finding from a genome wide association study (GWAS) was a surprise. In the brain, it turns out that TREM2 proteins are primarily made by microglia. These scavenging immune cells help to keep the brain healthy, acting as a clean-up crew that clears cellular debris, including the plaque-like amyloid-beta that is a hallmark of AD.

In subsequent studies, Haass and colleagues showed in mouse models of AD that TREM2 helps to shift microglia into high gear for clearing amyloid plaques [2]. This animal work and that of others helped to strengthen the case that TREM2 may play an important role in AD. But what did these data mean for people with this devastating condition?

There had been some hints of a connection between TREM2 and the progression of AD in humans. In the study published in Science Translational Medicine, the researchers took a deeper look by taking advantage of the NIH-funded Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI).

ADNI began more than a decade ago to develop methods for early AD detection, intervention, and treatment. The initiative makes all its data freely available to AD researchers all around the world. That allowed Ewers, Haass, and colleagues to focus their attention on 385 older ADNI participants, both with and without AD, who had been followed for an average of four years.

Their primary hypothesis was that individuals with AD and evidence of higher TREM2 levels at the outset of the study would show over the years less change in their cognitive abilities and in the volume of their hippocampus, a portion of the brain important for learning and memory. And, indeed, that’s exactly what they found.

In individuals with comparable AD, whether mild cognitive impairment or dementia, those having higher levels of a TREM2 fragment in their CSF showed a slower decline in memory. Those with evidence of a higher ratio of TREM2 relative to the tau protein in their CSF also progressed more slowly from normal cognition to early signs of AD or from mild cognitive impairment to full-blown dementia.

While it’s important to note that correlation isn’t causation, the findings suggest that treatments designed to boost TREM2 and the activation of microglia in the brain might hold promise for slowing the progression of AD in people. The challenge will be to determine when and how to target TREM2, and a great deal of research is now underway to make these discoveries.

Since its launch more than a decade ago, ADNI has made many important contributions to AD research. This new study is yet another fine example that should come as encouraging news to people with AD and their families.

References:

[1] Increased soluble TREM2 in cerebrospinal fluid is associated with reduced cognitive and clinical decline in Alzheimer’s disease. Ewers M, Franzmeier N, Suárez-Calvet M, Morenas-Rodriguez E, Caballero MAA, Kleinberger G, Piccio L, Cruchaga C, Deming Y, Dichgans M, Trojanowski JQ, Shaw LM, Weiner MW, Haass C; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Sci Transl Med. 2019 Aug 28;11(507).

[2] Loss of TREM2 function increases amyloid seeding but reduces plaque-associated ApoE. Parhizkar S, Arzberger T, Brendel M, Kleinberger G, Deussing M, Focke C, Nuscher B, Xiong M, Ghasemigharagoz A, Katzmarski N, Krasemann S, Lichtenthaler SF, Müller SA, Colombo A, Monasor LS, Tahirovic S, Herms J, Willem M, Pettkus N, Butovsky O, Bartenstein P, Edbauer D, Rominger A, Ertürk A, Grathwohl SA, Neher JJ, Holtzman DM, Meyer-Luehmann M, Haass C. Nat Neurosci. 2019 Feb;22(2):191-204.

Links:

Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias (National Institute on Aging/NIH)

Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (University of Southern California, Los Angeles)

Ewers Lab (University Hospital Munich, Germany)

Haass Lab (Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Germany)

German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases (Bonn)

Institute for Stroke and Dementia Research (Munich, Germany)

NIH Support: National Institute on Aging

The Brain Ripples Before We Remember

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Throw a stone into a quiet pond, and you’ll see ripples expand across the water from the point where it went in. Now, neuroscientists have discovered that a different sort of ripple—an electrical ripple—spreads across the human brain when it strives to recall memories.

In memory games involving 14 very special volunteers, an NIH-funded team found that the split second before a person nailed the right answer, tiny ripples of electrical activity appeared in two specific areas of the brain [1]. If the volunteer recalled an answer incorrectly or didn’t answer at all, the ripples were much less likely to appear. While many questions remain, the findings suggest that the short, high-frequency electrical waves seen in these brain ripples may play an unexpectedly important role in our ability to remember.

The new study, published in Science, builds on brain recording data compiled over the last several years by neurosurgeon and researcher Kareem Zaghloul at NIH’s National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS). Zaghloul’s surgical team often temporarily places 10-to-20 arrays of tiny electrodes into the brains of a people with drug-resistant epilepsy. As I’ve highlighted recently, the brain mapping procedure aims to pinpoint the source of a patient’s epileptic seizures. But, with a patient’s permission, the procedure also presents an opportunity to learn more about how the brain works, with exceptional access to its circuits.

One such opportunity is to explore how the brain stores and recalls memories. To do this, the researchers show their patient volunteers hundreds of pairs of otherwise unrelated words, such as “pencil and bishop” or “orange and navy.” Later, they show them one of the words and test their memory to recall the right match. All the while, electrodes record the brain’s electrical activity.

Previously published studies by Zaghloul’s lab [2, 3] and many others have shown that memory involves the activation of a number of brain regions. That includes the medial temporal lobe, which is involved in forming and retrieving memories, and the prefrontal cortex, which helps in organizing memories in addition to its roles in “executive functions,” such as planning and setting goals. Those studies also have highlighted a role for the temporal association cortex, another portion of the temporal lobe involved in processing experiences and words.

In their data collected in patients with epilepsy, Zaghloul’s team’s earlier studies had uncovered some telltale patterns. For instance, when a person correctly recalled a word pair, the brain showed patterns of activity that looked quite similar to those present when he or she first learned to make a word association.

Alex Vaz, one of Zaghloul’s doctoral students, thought there might be more to the story. There was emerging evidence in rodents that brain ripples—short bursts of high frequency electrical activity—are involved in learning. There was also some evidence in people that such ripples might be important for solidifying memories during sleep. Vaz wondered whether they might find evidence of ripples as well in data gathered from people who were awake.

Vaz’s hunch was correct. The reanalysis revealed ripples of electricity in the medial temporal lobe and the temporal association cortex. When a person correctly recalled a word pair, those two brain areas rippled at the same time.

Further analysis showed that the ripples appeared in those two areas a few milliseconds before a volunteer remembered a word and gave a correct answer. Your brain is working on finding an answer before you are fully aware of it! Those ripples also appear to trigger brain waves that look similar to those observed in the association cortex when a person first learned a word pair.

The finding suggests that ripples in this part of the brain precede and may help to prompt the larger brain waves associated with replaying and calling to mind a particular memory. For example, hearing the words, “The Fab Four” may ripple into a full memory of a favorite Beatles album (yes! Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band) or, if you were lucky enough, a memorable concert back in the day (I never had that chance).

Zaghloul’s lab continues to study the details of these ripples to learn even more about how they may influence other neural signals and features involved in memory. So, the next time you throw a stone into a quiet pond and watch the ripples, perhaps it will trigger an electrical ripple in your brain to remember this blog and ruminate about this fascinating new discovery in neuroscience.

References:

[1] Coupled ripple oscillations between the medial temporal lobe and neocortex retrieve human memory. Vaz AP, Inati SK, Brunel N, Zaghloul KA. Science. 2019 Mar 1;363(6430):975-978.

[2] Cued Memory Retrieval Exhibits Reinstatement of High Gamma Power on a Faster Timescale in the Left Temporal Lobe and Prefrontal Cortex. Yaffe RB, Shaikhouni A, Arai J, Inati SK, Zaghloul KA. J Neurosci. 2017 Apr 26;37(17):4472-4480.

[3] Human Cortical Neurons in the Anterior Temporal Lobe Reinstate Spiking Activity during Verbal Memory Retrieval. Jang AI, Wittig JH Jr, Inati SK, Zaghloul KA. Curr Biol. 2017 Jun 5;27(11):1700-1705.e5.

Links:

Epilepsy Information Page (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke/NIH)

Brain Basics (NINDS)

Zaghloul Lab (NINDS)

NIH Support: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; National Institute of General Medical Sciences

Sleep Loss Encourages Spread of Toxic Alzheimer’s Protein

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

In addition to memory loss and confusion, many people with Alzheimer’s disease have trouble sleeping. Now an NIH-funded team of researchers has evidence that the reverse is also true: a chronic lack of sleep may worsen the disease and its associated memory loss.

The new findings center on a protein called tau, which accumulates in abnormal tangles in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s disease. In the healthy brain, active neurons naturally release some tau during waking hours, but it normally gets cleared away during sleep. Essentially, your brain has a system for taking the garbage out while you’re off in dreamland.

The latest findings in studies of mice and people further suggest that sleep deprivation upsets this balance, allowing more tau to be released, accumulate, and spread in toxic tangles within brain areas important for memory. While more study is needed, the findings suggest that regular and substantial sleep may play an unexpectedly important role in helping to delay or slow down Alzheimer’s disease.

It’s long been recognized that Alzheimer’s disease is associated with the gradual accumulation of beta-amyloid peptides and tau proteins, which form plaques and tangles that are considered hallmarks of the disease. It has only more recently become clear that, while beta-amyloid is an early sign of the disease, tau deposits track more closely with disease progression and a person’s cognitive decline.

Such findings have raised hopes among researchers including David Holtzman, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, that tau-targeting treatments might slow this devastating disease. Though much of the hope has focused on developing the right drugs, some has also focused on sleep and its nightly ability to reset the brain’s metabolic harmony.

In the new study published in Science, Holtzman’s team set out to explore whether tau levels in the brain naturally are tied to the sleep-wake cycle [1]. Earlier studies had shown that tau is released in small amounts by active neurons. But when neurons are chronically activated, more tau gets released. So, do tau levels rise when we’re awake and fall during slumber?

The Holtzman team found that they do. The researchers measured tau levels in brain fluid collected from mice during their normal waking and sleeping hours. (Since mice are nocturnal, they sleep primarily during the day.) The researchers found that tau levels in brain fluid nearly double when the animals are awake. They also found that sleep deprivation caused tau levels in brain fluid to double yet again.

These findings were especially interesting because Holtzman’s team had already made a related finding in people. The team found that healthy adults forced to pull an all-nighter had a 30 percent increase on average in levels of unhealthy beta-amyloid in their cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).

The researchers went back and reanalyzed those same human samples for tau. Sure enough, the tau levels were elevated on average by about 50 percent.

Once tau begins to accumulate in brain tissue, the protein can spread from one brain area to the next along neural connections. So, Holtzman’s team wondered whether a lack of sleep over longer periods also might encourage tau to spread.

To find out, mice engineered to produce human tau fibrils in their brains were made to stay up longer than usual and get less quality sleep over several weeks. Those studies showed that, while less sleep didn’t change the original deposition of tau in the brain, it did lead to a significant increase in tau’s spread. Intriguingly, tau tangles in the animals appeared in the same brain areas affected in people with Alzheimer’s disease.

Another report by Holtzman’s team appearing early last month in Science Translational Medicine found yet another link between tau and poor sleep. That study showed that older people who had more tau tangles in their brains by PET scanning had less slow-wave, deep sleep [2].

Together, these new findings suggest that Alzheimer’s disease and sleep loss are even more intimately intertwined than had been realized. The findings suggest that good sleep habits and/or treatments designed to encourage plenty of high quality Zzzz’s might play an important role in slowing Alzheimer’s disease. On the other hand, poor sleep also might worsen the condition and serve as an early warning sign of Alzheimer’s.

For now, the findings come as an important reminder that all of us should do our best to get a good night’s rest on a regular basis. Sleep deprivation really isn’t a good way to deal with overly busy lives (I’m talking to myself here). It isn’t yet clear if better sleep habits will prevent or delay Alzheimer’s disease, but it surely can’t hurt.

References:

[1] The sleep-wake cycle regulates brain interstitial fluid tau in mice and CSF tau in humans. Holth JK, Fritschi SK, Wang C, Pedersen NP, Cirrito JR, Mahan TE, Finn MB, Manis M, Geerling JC, Fuller PM, Lucey BP, Holtzman DM. Science. 2019 Jan 24.

[2] Reduced non-rapid eye movement sleep is associated with tau pathology in early Alzheimer’s disease. Lucey BP, McCullough A, Landsness EC, Toedebusch CD, McLeland JS, Zaza AM, Fagan AM, McCue L, Xiong C, Morris JC, Benzinger TLS, Holtzman DM. Sci Transl Med. 2019 Jan 9;11(474).

Links:

Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias (National Institute on Aging/NIH)

Accelerating Medicines Partnership: Alzheimer’s Disease (NIH)

Holtzman Lab (Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis)

NIH Support: National Institute on Aging; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences; National Cancer Institute; National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering

Distinctive Brain ‘Subnetwork’ Tied to Feeling Blue

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: :iStock/kieferpix

Experiencing a range of emotions is a normal part of human life, but much remains to be discovered about the neuroscience of mood. In a step toward unraveling some of those biological mysteries, researchers recently identified a distinctive pattern of brain activity associated with worsening mood, particularly among people who tend to be anxious.

In the new study, researchers studied 21 people who were hospitalized as part of preparation for epilepsy surgery, and took continuous recordings of the brain’s electrical activity for seven to 10 days. During that same period, the volunteers also kept track of their moods. In 13 of the participants, low mood turned out to be associated with stronger activity in a “subnetwork” that involved crosstalk between the brain’s amygdala, which mediates fear and other emotions, and the hippocampus, which aids in memory.

A New Piece of the Alzheimer’s Puzzle

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: National Institute on Aging, NIH

For the past few decades, researchers have been busy uncovering genetic variants associated with an increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [1]. But there’s still a lot to learn about the many biological mechanisms that underlie this devastating neurological condition that affects as many as 5 million Americans [2].

As an example, an NIH-funded research team recently found that AD susceptibility may hinge not only upon which gene variants are present in a person’s DNA, but also how RNA messages encoded by the affected genes are altered to produce proteins [3]. After studying brain tissue from more than 450 deceased older people, the researchers found that samples from those with AD contained many more unusual RNA messages than those without AD.

Study Suggests Light Exercise Helps Memory

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: iStock/Wavebreakmedia

How much exercise does it take to boost your memory skills? Possibly a lot less than you’d think, according to the results of a new study that examined the impact of light exercise on memory.

In their study of 36 healthy young adults, researchers found surprisingly immediate improvements in memory after just 10 minutes of low-intensity pedaling on a stationary bike [1]. Further testing by the international research team reported that the quick, light workout—which they liken in intensity to a short yoga or tai chi session—was associated with heightened activity in the brain’s hippocampus. That’s noteworthy because the hippocampus is known for its involvement in remembering facts and events.

Unlocking the Brain’s Memory Retrieval System

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

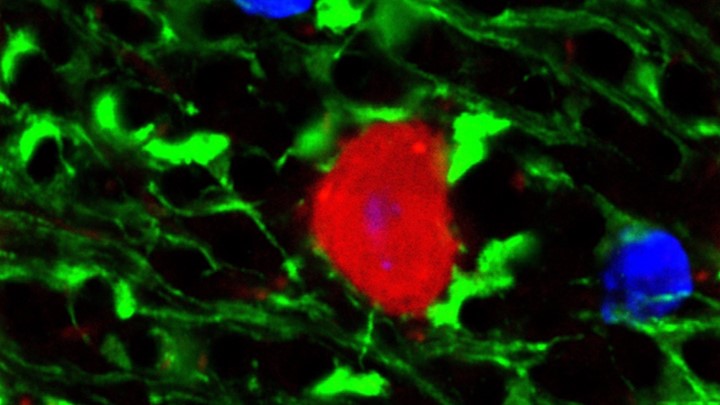

Credit:Sahay Lab, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston

Play the first few bars of any widely known piece of music, be it The Star-Spangled Banner, Beethoven’s Fifth, or The Rolling Stones’ (I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction, and you’ll find that many folks can’t resist filling in the rest of the melody. That’s because the human brain thrives on completing familiar patterns. But, as we grow older, our pattern completion skills often become more error prone.

This image shows some of the neural wiring that controls pattern completion in the mammalian brain. Specifically, you’re looking at a cross-section of a mouse hippocampus that’s packed with dentate granule neurons and their signal-transmitting arms, called axons, (light green). Note how the axons’ short, finger-like projections, called filopodia (bright green), are interacting with a neuron (red) to form a “memory trace” network. Functioning much like an online search engine, memory traces use bits of incoming information, like the first few notes of a song, to locate and pull up more detailed information, like the complete song, from the brain’s repository of memories in the cerebral cortex.

New Evidence Suggests Aging Brains Continue to Make New Neurons

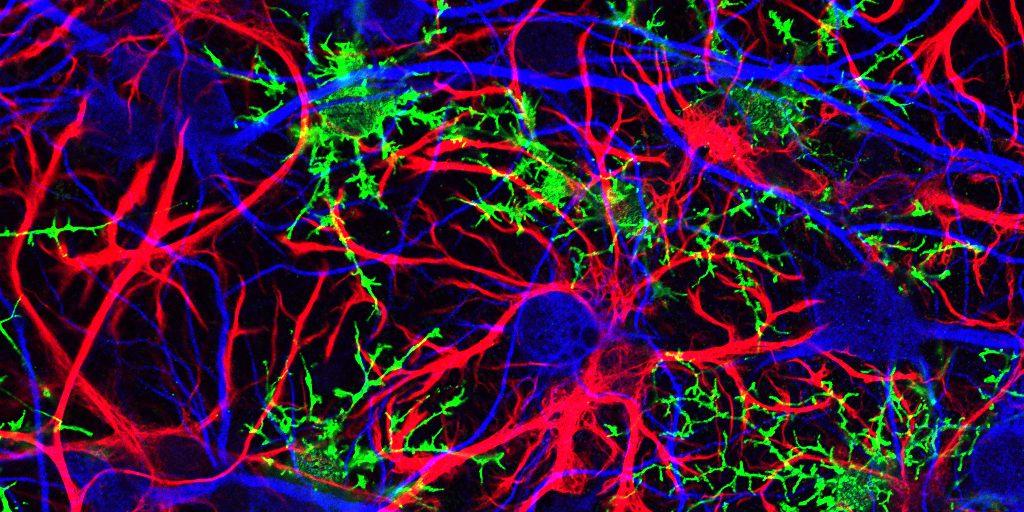

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: Mammalian hippocampal tissue. Immunofluorescence microscopy showing neurons (blue) interacting with neural astrocytes (red) and oligodendrocytes (green).

Credit: Jonathan Cohen, Fields Lab, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, NIH

There’s been considerable debate about whether the human brain has the capacity to make new neurons into adulthood. Now, a recently published study offers some compelling new evidence that’s the case. In fact, the latest findings suggest that a healthy person in his or her seventies may have about as many young neurons in a portion of the brain essential for learning and memory as a teenager does.

As reported in the journal Cell Stem Cell, researchers examined the brains of healthy people, aged 14 to 79, and found similar numbers of young neurons throughout adulthood [1]. Those young neurons persisted in older brains that showed other signs of decline, including a reduced ability to produce new blood vessels and form new neural connections. The researchers also found a smaller reserve of quiescent, or inactive, neural stem cells in a brain area known to support cognitive-emotional resilience, the ability to cope with and bounce back from stressful circumstances.

While more study is clearly needed, the findings suggest healthy elderly people may have more cognitive reserve than is commonly believed. However, the findings may also help to explain why even perfectly healthy older people often find it difficult to face new challenges, such as travel or even shopping at a different grocery store, that wouldn’t have fazed them earlier in life.

Previous Page Next Page