neurogenesis

New Evidence Suggests Aging Brains Continue to Make New Neurons

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

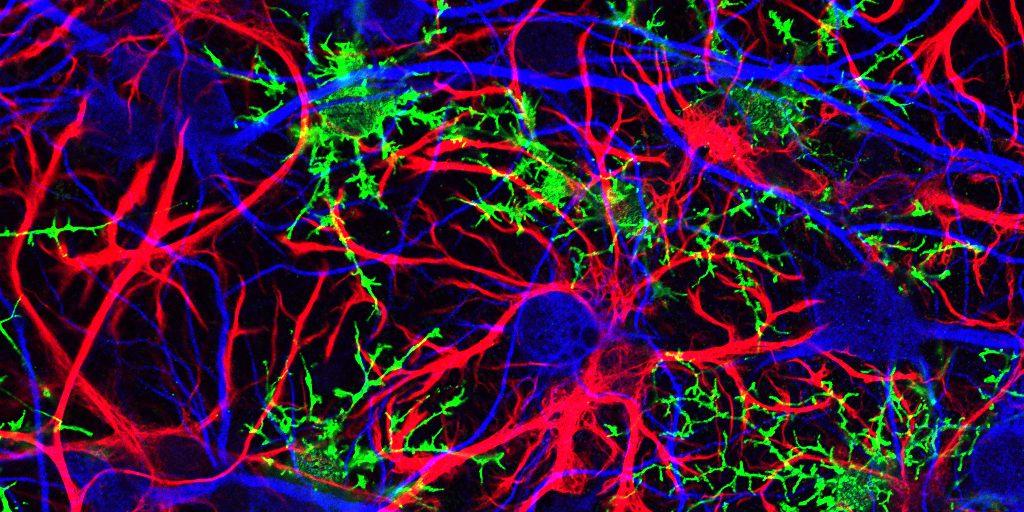

Caption: Mammalian hippocampal tissue. Immunofluorescence microscopy showing neurons (blue) interacting with neural astrocytes (red) and oligodendrocytes (green).

Credit: Jonathan Cohen, Fields Lab, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, NIH

There’s been considerable debate about whether the human brain has the capacity to make new neurons into adulthood. Now, a recently published study offers some compelling new evidence that’s the case. In fact, the latest findings suggest that a healthy person in his or her seventies may have about as many young neurons in a portion of the brain essential for learning and memory as a teenager does.

As reported in the journal Cell Stem Cell, researchers examined the brains of healthy people, aged 14 to 79, and found similar numbers of young neurons throughout adulthood [1]. Those young neurons persisted in older brains that showed other signs of decline, including a reduced ability to produce new blood vessels and form new neural connections. The researchers also found a smaller reserve of quiescent, or inactive, neural stem cells in a brain area known to support cognitive-emotional resilience, the ability to cope with and bounce back from stressful circumstances.

While more study is clearly needed, the findings suggest healthy elderly people may have more cognitive reserve than is commonly believed. However, the findings may also help to explain why even perfectly healthy older people often find it difficult to face new challenges, such as travel or even shopping at a different grocery store, that wouldn’t have fazed them earlier in life.

Zika and Birth Defects: The Evidence Mounts

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: Human neural progenitor cells (gray) infected with Zika virus (green) increased the enzyme caspase-3 (red), suggesting increased cell death.

Credit: Sarah C. Ogden, Florida State University, Tallahassee

Recently, public health officials have raised major concerns over the disturbing spread of the mosquito-borne Zika virus among people living in and traveling to many parts of Central and South America [1]. While the symptoms of Zika infection are typically mild, grave concerns have arisen about its potential impact during pregnancy. The concerns stem from the unusual number of births of children with microcephaly, a very serious condition characterized by a small head and damaged brain, coinciding with the spread of Zika virus. Now, two new studies strengthen the connection between Zika and an array of birth defects, including, but not limited to, microcephaly.

In the first study, NIH-funded laboratory researchers show that Zika virus can infect and kill human neural progenitor cells [2]. Those progenitor cells give rise to the cerebral cortex, a portion of the brain often affected in children with microcephaly. The second study, involving a small cohort of women diagnosed with Zika virus during their pregnancies in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, suggests that the attack rate is disturbingly high, and microcephaly is just one of many risks to the developing fetus. [3]