The Amazing Brain: Turning Conventional Wisdom on Brain Anatomy on its Head

Posted on by John Ngai, PhD, NIH BRAIN Initiative

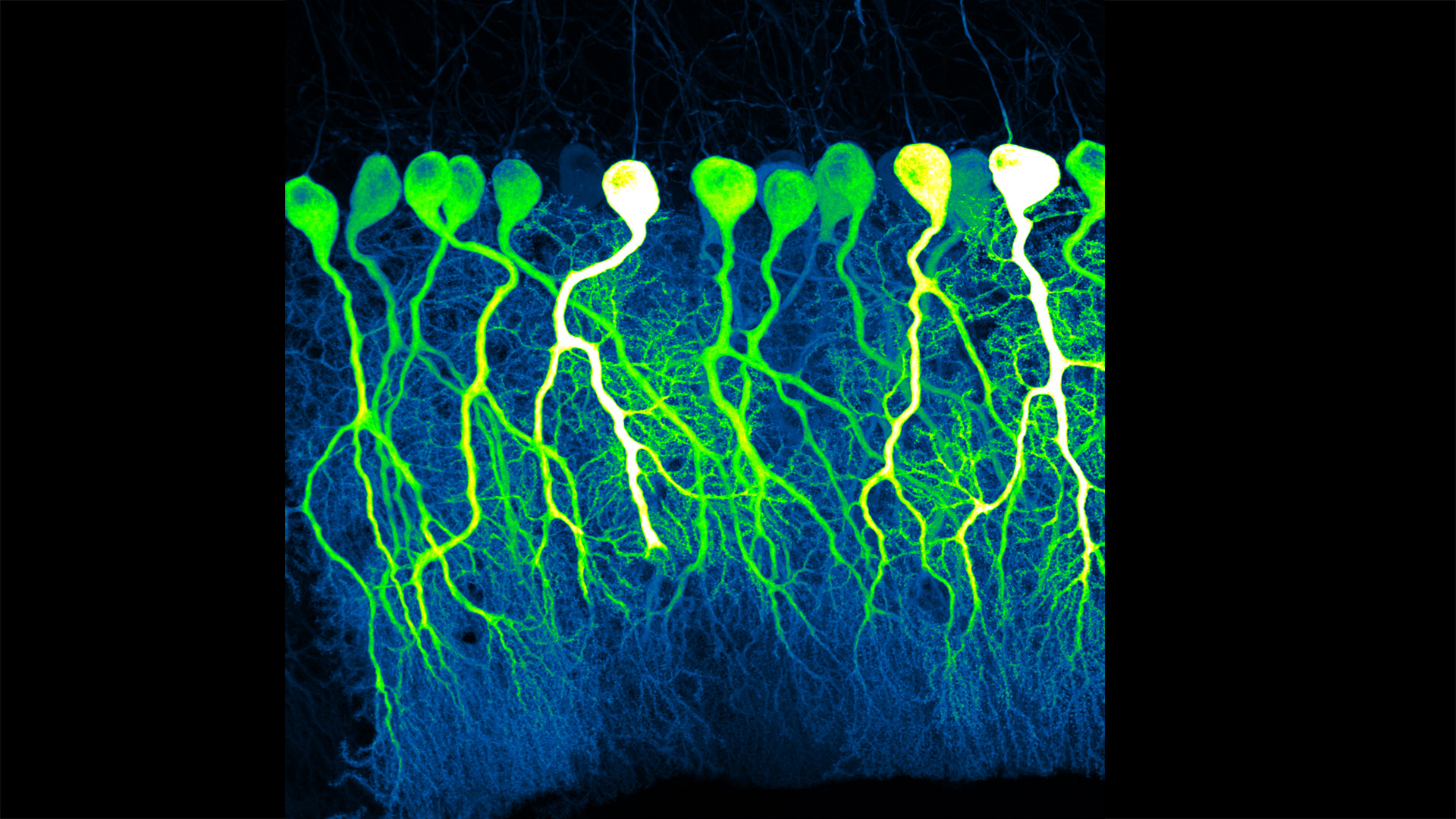

Silas Busch at the University of Chicago captured this slightly eerie scene, noting it reminded him of people shuffling through the dark of night. What you’re really seeing are some of the largest neurons in the mammalian brain, known as Purkinje cells. The photo won first place this year in the Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies® (BRAIN) Initiative’s annual Show Us Your BRAINs! Photo and Video Contest.

While humans have them, too, the Purkinje cells pictured here are in the brain of a mouse. The head-like shapes you see in the image are the so-called soma, or the neurons’ cell bodies. Extending downwards are the heavily branched dendrites, which act like large antennae, receiving thousands of inputs from the rest of the body.

One reason this picture is such a standout, explains Busch, is because of what you don’t see. You’ll notice that only a few cells are fluorescently labeled and therefore lit up in green, leaving the rest in shadows. As a result, it’s possible to trace the detailed branches of individual Purkinje cells and make out their intricate forms. As it turns out, this ability to trace Purkinje cells so precisely led Busch, who is a graduate student in Christian Hansel’s lab focused on the neurobiology of learning and memory, to a surprising discovery, which the pair recently reported in Science.1

Purkinje cells connect to nerve fibers that “climb up” from the brain stem, which connects your brain and spinal cord to help control breathing, heart rate, balance and more. Scientists thought that each Purkinje cell received only one of these climbing fibers from the brain stem on its single primary branch.

However, after carefully tracing thousands of Purkinje cells in brain tissue from both mice and humans, the researchers have now shown that Purkinje cells and climbing fibers don’t always have a simple one-to-one relationship. In fact, Busch and Hansel found more than 95 percent of human Purkinje cells have multiple primary branches, not just one. In mice, that ratio is closer to 50 percent.

The researchers went on to show that mouse Purkinje cells with multiple primary branches often also receive multiple climbing fibers. The discovery rewrites the textbook idea of how Purkinje cells in the brain and climbing fibers from the brainstem are anatomically arranged.

Not surprisingly, those extra connections in the cerebellum (located in the back of the brain) also have important functional implications. When Purkinje cells have just one climbing fiber input, the new study shows, the whole cell receives each signal equally and responds accordingly. But, in cells with multiple climbing fiber inputs, the researchers could detect differences across a single cell depending on which primary branch received an input.

What this means is that Purkinje cells in the brain have much more computational power than had been appreciated. That extra brain power has important implications for understanding how brain circuits can adapt and respond to changes outside the body that now warrant further study. The new findings may have implications also for understanding the role of these Purkinje cell connections in some neurological and developmental disorders, including autism2 and a movement disorder known as cerebellar ataxia.

As they say, a picture is worth a thousand words. And this winning image comes as a reminder that we still have more to learn from careful study of basic brain anatomy, with important implications for human health and disease.

References:

[1] SE Busch and C Hansel. Climbing fiber multi-innervation of mouse Purkinje dendrites with arborization common to human. Science. DOI: 10.1126/science.adi1024. (2023).

[2] DH Simmons et al. Sensory Over-responsivity and Aberrant Plasticity in Cerebellar Cortex in a Mouse Model of Syndromic Autism. Biological Psychiatry: Global Open Science. DOI: 10.1016/j.bpsgos.2021.09.004. (2021).

I had always “thought” this was how our brains were “wired”!

Now there’s actual proof. I wish I would have at least drawn what I was thinking…

Another missed opportunity for Fame! lol.