blood platelets

Study Ties COVID-19-Related Syndrome in Kids to Altered Immune System

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Most children infected with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, develop only a mild illness. But, days or weeks later, a small percentage of kids go on to develop a puzzling syndrome known as multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C). This severe inflammation of organs and tissues can affect the heart, lungs, kidneys, brain, skin, and eyes.

Thankfully, most kids with MIS-C respond to treatment and make rapid recoveries. But, tragically, MIS-C can sometimes be fatal.

With COVID-19 cases in children having increased by 21 percent in the United States since early August [2], NIH and others are continuing to work hard on getting a handle on this poorly understood complication. Many think that MIS-C isn’t a direct result of the virus, but seems more likely to be due to an intense autoimmune response. Indeed, a recent study in Nature Medicine [1] offers some of the first evidence that MIS-C is connected to specific changes in the immune system that, for reasons that remain mysterious, sometimes follow COVID-19.

These findings come from Shane Tibby, a researcher at Evelina London Children’s Hospital, London. United Kingdom; Manu Shankar-Hari, a scientist at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, London; and colleagues. The researchers enlisted 25 children, ages 7 to 14, who developed MIS-C in connection with COVID-19. In search of clues, they examined blood samples collected from the children during different stages of their care, starting when they were most ill through recovery and follow-up. They then compared the samples to those of healthy children of the same ages.

What they found was a complex array of immune disruptions. The children had increased levels of various inflammatory molecules known as cytokines, alongside raised levels of other markers suggesting tissue damage—such as troponin, which indicates heart muscle injury.

The neutrophils, monocytes, and other white blood cells that rapidly respond to infections were activated as expected. But the levels of certain white blood cells called T lymphocytes were paradoxically reduced. Interestingly, despite the low overall numbers of T lymphocytes, particular subsets of them appeared activated as though fighting an infection. While the children recovered, those differences gradually disappeared as the immune system returned to normal.

It has been noted that MIS-C bears some resemblance to an inflammatory condition known as Kawasaki disease, which also primarily affects children. While there are similarities, this new work shows that MIS-C is a distinct illness associated with COVID-19. In fact, only two children in the study met the full criteria for Kawasaki disease based on the clinical features and symptoms of their illness.

Another recent study from the United Kingdom, reported several new symptoms of MIS-C [3]. They include headaches, tiredness, muscle aches, and sore throat. Researchers also determined that the number of platelets was much lower in the blood of children with MIS-C than in those without the condition. They proposed that evaluating a child’s symptoms along with his or her platelet level could help to diagnose MIS-C.

It will now be important to learn much more about the precise mechanisms underlying these observed changes in the immune system and how best to treat or prevent them. In support of this effort, NIH recently announced $20 million in research funding dedicated to the development of approaches that identify children at high risk for developing MIS-C [4].

The hope is that this new NIH effort, along with other continued efforts around the world, will elucidate the factors influencing the likelihood that a child with COVID-19 will develop MIS-C. Such insights are essential to allow doctors to intervene as early as possible and improve outcomes for this potentially serious condition.

References:

[1] Peripheral immunophenotypes in children with multisystem inflammatory syndrome associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Carter MJ, Fish M, Jennings A, Doores KJ, Wellman P, Seow J, Acors S, Graham C, Timms E, Kenny J, Neil S, Malim MH, Tibby SM, Shankar-Hari M. Nat Med. 2020 Aug 18.

[2] Children and COVID-19: State-Level Data Report. American Academy of Pediatrics. August 24, 2020.

[3] Clinical characteristics of children and young people admitted to hospital with covid-19 in United Kingdom: prospective multicentre observational cohort study. Swann OV, Holden KA, Turtle L, Harrison EW, Docherty AB, Semple MG, et al. Br Med J. 2020 Aug 17.

[4] NIH-funded project seeks to identify children at risk for MIS-C. NIH. August 7, 2020.

Links:

Coronavirus (COVID-19) (NIH)

Kawasaki Disease (Genetic and Rare Disease Information Center/National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences/NIH)

Shane Tibby (Evelina London Children’s Hospital, London)

Manu Shankar-Hari (King’s College, London)

NIH Support: Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; Office of the Director; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases; National Institute on Drug Abuse; National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities; Fogarty International Center

Building a Better Bacterial Trap for Sepsis

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Spiders spin webs to catch insects for dinner. It turns out certain human immune cells, called neutrophils, do something similar to trap bacteria in people who develop sepsis, an uncontrolled, systemic infection that poses a major challenge in hospitals.

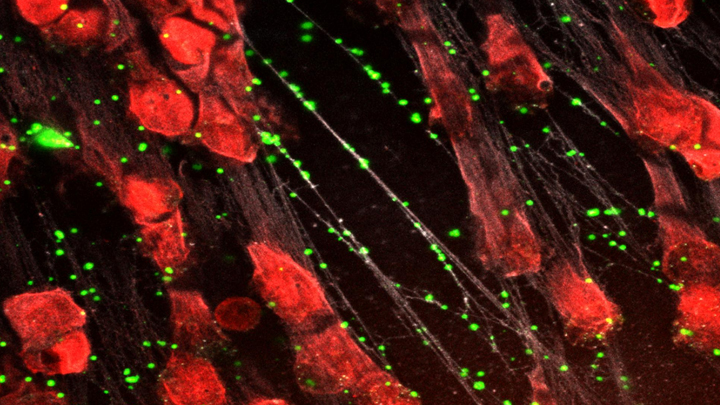

When activated to catch sepsis-causing bacteria or other pathogens, neutrophils rupture and spew sticky, spider-like webs made of DNA and antibacterial proteins. Here in red you see one of these so-called neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) that’s ensnared Staphylococcus aureus (green), a type of bacteria known for causing a range of illnesses from skin infections to pneumonia.

Yet this image, which comes from Kandace Gollomp and Mortimer Poncz at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, is much more than a fascinating picture. It demonstrates a potentially promising new way to treat sepsis.

The researchers’ strategy involves adding a protein called platelet factor 4 (PF4), which is released by clot-forming blood platelets, to the NETs. PF4 readily binds to NETs and enhances their capture of bacteria. A modified antibody (white), which is a little hard to see, coats the PF4-bound NET above. This antibody makes the NETs even better at catching and holding onto bacteria. Other immune cells then come in to engulf and clean up the mess.

Until recently, most discussions about NETs assumed they were causing trouble, and therefore revolved around how to prevent or get rid of them while treating sepsis. But such strategies faced a major obstacle. By the time most people are diagnosed with sepsis, large swaths of these NETs have already been spun. In fact, destroying them might do more harm than good by releasing entrapped bacteria and other toxins into the bloodstream.

In a recent study published in the journal Blood, Gollomp’s team proposed flipping the script [1]. Rather than prevent or destroy NETs, why not modify them to work even better to fight sepsis? Their idea: Make NETs even stickier to catch more bacteria. This would lower the number of bacteria and help people recover from sepsis.

Gollomp recalled something lab member Anna Kowalska had noted earlier in unrelated mouse studies. She’d observed that high levels of PF4 were protective in mice with sepsis. Gollomp and her colleagues wondered if the PF4 might also be used to reinforce NETs. Sure enough, Gollomp’s studies showed that PF4 will bind to NETs, causing them to condense and resist break down.

Subsequent studies in mice and with human NETs cast in a synthetic blood vessel suggest that this approach might work. Treatment with PF4 greatly increased the number of bacteria captured by NETs. It also kept NETs intact and holding tightly onto their toxic contents. As a result, mice with sepsis fared better.

Of course, mice are not humans. More study is needed to see if the same strategy can help people with sepsis. For example, it will be important to determine if modified NETs are difficult for the human body to clear. Also, Gollomp thinks this approach might be explored for treating other types of bacterial infections.

Still, the group’s initial findings come as encouraging news for hospital staff and administrators. If all goes well, a future treatment based on this intriguing strategy may one day help to reduce the 270,000 sepsis-related deaths in the U.S. and its estimated more than $24 billion annual price tag for our nation’s hospitals [2, 3].

References:

[1] Fc-modified HIT-like monoclonal antibody as a novel treatment for sepsis. Gollomp K, Sarkar A, Harikumar S, Seeholzer SH, Arepally GM, Hudock K, Rauova L, Kowalska MA, Poncz M. Blood. 2020 Mar 5;135(10):743-754.

[2] Sepsis, Data & Reports, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Feb. 14, 2020.

[3] National inpatient hospital costs: The most expensive conditions by payer, 2013: Statistical Brief #204. Torio CM, Moore BJ. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2016 May.

Links:

Sepsis (National Institute of General Medical Sciences/NIH)

Kandace Gollomp (The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, PA)

Mortimer Poncz (The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, PA)

NIH Support: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

An Aspirin a Day for Older People Doesn’t Prolong Healthy Lifespan

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: iStock/thodonal

Many older people who’ve survived a heart attack or stroke take low-dose aspirin every day to help prevent further cardiovascular problems [1]. There is compelling evidence that this works. But should perfectly healthy older folks follow suit?

Most of us would have guessed “yes”—but the answer appears to be “no” when you consider the latest scientific evidence. Recently, a large, international study of older people without a history of cardiovascular disease found that those who took a low-dose aspirin daily over more than 4 years weren’t any healthier than those who didn’t. What’s more, there were some unexpected indications that low-dose aspirin might even boost the risk of death.