heart attack

Can Autoimmune Antibodies Explain Blood Clots in COVID-19?

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

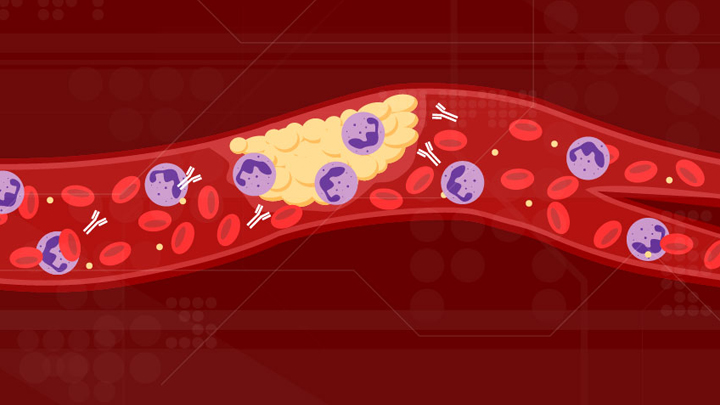

For people with severe COVID-19, one of the most troubling complications is abnormal blood clotting that puts them at risk of having a debilitating stroke or heart attack. A new study suggests that SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, doesn’t act alone in causing blood clots. The virus seems to unleash mysterious antibodies that mistakenly attack the body’s own cells to cause clots.

The NIH-supported study, published in Science Translational Medicine, uncovered at least one of these autoimmune antiphospholipid (aPL) antibodies in about half of blood samples taken from 172 patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Those with higher levels of the destructive autoantibodies also had other signs of trouble. They included greater numbers of sticky, clot-promoting platelets and NETs, webs of DNA and protein that immune cells called neutrophils spew to ensnare viruses during uncontrolled infections, but which can lead to inflammation and clotting. These observations, coupled with the results of lab and mouse studies, suggest that treatments to control those autoantibodies may hold promise for preventing the cascade of events that produce clots in people with COVID-19.

Our blood vessels normally strike a balance between producing clotting and anti-clotting factors. This balance keeps us ready to seal up vessels after injury, but otherwise to keep our blood flowing at just the right consistency so that neutrophils and platelets don’t stick and form clots at the wrong time. But previous studies have suggested that SARS-CoV-2 can tip the balance toward promoting clot formation, raising questions about which factors also get activated to further drive this dangerous imbalance.

To learn more, a team of physician-scientists, led by Yogendra Kanthi, a newly recruited Lasker Scholar at NIH’s National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and his University of Michigan colleague Jason S. Knight, looked to various types of aPL autoantibodies. These autoantibodies are a major focus in the Knight Lab’s studies of an acquired autoimmune clotting condition called antiphospholipid syndrome. In people with this syndrome, aPL autoantibodies attack phospholipids on the surface of cells including those that line blood vessels, leading to increased clotting. This syndrome is more common in people with other autoimmune or rheumatic conditions, such as lupus.

It’s also known that viral infections, including COVID-19, produce a transient increase in aPL antibodies. The researchers wondered whether those usually short-lived aPL antibodies in COVID-19 could trigger a condition similar to antiphospholipid syndrome.

The researchers showed that’s exactly the case. In lab studies, neutrophils from healthy people released twice as many NETs when cultured with autoantibodies from patients with COVID-19. That’s remarkably similar to what had been seen previously in such studies of the autoantibodies from patients with established antiphospholipid syndrome. Importantly, their studies in the lab further suggest that the drug dipyridamole, used for decades to prevent blood clots, may help to block that antibody-triggered release of NETs in COVID-19.

The researchers also used mouse models to confirm that autoantibodies from patients with COVID-19 actually led to blood clots. Again, those findings closely mirror what happens in mouse studies testing the effects of antibodies from patients with the most severe forms of antiphospholipid syndrome.

While more study is needed, the findings suggest that treatments directed at autoantibodies to limit the formation of NETs might improve outcomes for people severely ill with COVID-19. The researchers note that further study is needed to determine what triggers autoantibodies in the first place and how long they last in those who’ve recovered from COVID-19.

The researchers have already begun enrolling patients into a modest scale clinical trial to test the anti-clotting drug dipyridamole in patients who are hospitalized with COVID-19, to find out if it can protect against dangerous blood clots. These observations may also influence the design of the ACTIV-4 trial, which is testing various antithrombotic agents in outpatients, inpatients, and convalescent patients. Kanthi and Knight suggest it may also prove useful to test infected patients for aPL antibodies to help identify and improve treatment for those who may be at especially high risk for developing clots. The hope is this line of inquiry ultimately will lead to new approaches for avoiding this very troubling complication in patients with severe COVID-19.

Reference:

[1] Prothrombotic autoantibodies in serum from patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Zuo Y, Estes SK, Ali RA, Gandhi AA, Yalavarthi S, Shi H, Sule G, Gockman K, Madison JA, Zuo M, Yadav V, Wang J, Woodard W, Lezak SP, Lugogo NL, Smith SA, Morrissey JH, Kanthi Y, Knight JS. Sci Transl Med. 2020 Nov 2:eabd3876.

Links:

Coronavirus (COVID-19) (NIH)

Antiphospholipid Antibody Syndrome (National Heart Lung and Blood Institute/NIH)

Kanthi Lab (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Bethesda, MD)

Knight Lab (University of Michigan)

ACTIV (NIH)

NIH Support: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

An Aspirin a Day for Older People Doesn’t Prolong Healthy Lifespan

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: iStock/thodonal

Many older people who’ve survived a heart attack or stroke take low-dose aspirin every day to help prevent further cardiovascular problems [1]. There is compelling evidence that this works. But should perfectly healthy older folks follow suit?

Most of us would have guessed “yes”—but the answer appears to be “no” when you consider the latest scientific evidence. Recently, a large, international study of older people without a history of cardiovascular disease found that those who took a low-dose aspirin daily over more than 4 years weren’t any healthier than those who didn’t. What’s more, there were some unexpected indications that low-dose aspirin might even boost the risk of death.

Missing Genes Point to Possible Drug Targets

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Every person’s genetic blueprint, or genome, is unique because of variations that occasionally occur in our DNA sequences. Most of those are passed on to us from our parents. But not all variations are inherited—each of us carries 60 to 100 “new mutations” that happened for the first time in us. Some of those variations can knock out the function of a gene in ways that lead to disease or other serious health problems, particularly in people unlucky enough to have two malfunctioning copies of the same gene. Recently, scientists have begun to identify rare individuals who have loss-of-function variations that actually seem to improve their health—extraordinary discoveries that may help us understand how genes work as well as yield promising new drug targets that may benefit everyone.

Every person’s genetic blueprint, or genome, is unique because of variations that occasionally occur in our DNA sequences. Most of those are passed on to us from our parents. But not all variations are inherited—each of us carries 60 to 100 “new mutations” that happened for the first time in us. Some of those variations can knock out the function of a gene in ways that lead to disease or other serious health problems, particularly in people unlucky enough to have two malfunctioning copies of the same gene. Recently, scientists have begun to identify rare individuals who have loss-of-function variations that actually seem to improve their health—extraordinary discoveries that may help us understand how genes work as well as yield promising new drug targets that may benefit everyone.

In a study published in the journal Nature, a team partially funded by NIH sequenced all 18,000 protein-coding genes in more than 10,500 adults living in Pakistan [1]. After finding that more than 17 percent of the participants had at least one gene completely “knocked out,” researchers could set about analyzing what consequences—good, bad, or neutral—those loss-of-function variations had on their health and well-being.

Cool Videos: Heart Attack

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Up next in our scientific film fest is an original music video, straight from the Big Apple. Created by researchers at The Rockefeller University, this song-and-dance routine provides an entertaining—and informative—look at how blood clots form, their role in causing heart attacks, and what approaches are being tried to break up these clots.

Before (or after!) you hit “play,” it might help to take a few moments to review the scientists’ description of their efforts: the key to saving the lives of heart attack victims lies in the molecules that control how blood vessels become clogged. This molecular biomedicine music video explains how ischemic injury can be prevented shortly after heart attack symptoms begin: clot blocking. The science is the collaborative work of Dr. Barry Coller of Rockefeller, Dr. Craig Thomas and his colleagues at the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), and Dr. Marta Filizola and her Mount Sinai colleagues.

Links:

Laboratory of Blood and Vascular Biology, The Rockefeller University

Filizola Laboratory, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai

Center for Clinical and Translational Science, The Rockefeller University

Clinical and Translational Science Awards (NCATS/NIH)

NIH Common Fund Video Competition

NIH support: Common Fund; National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences

Snapshots of Life: Mending Broken Hearts

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

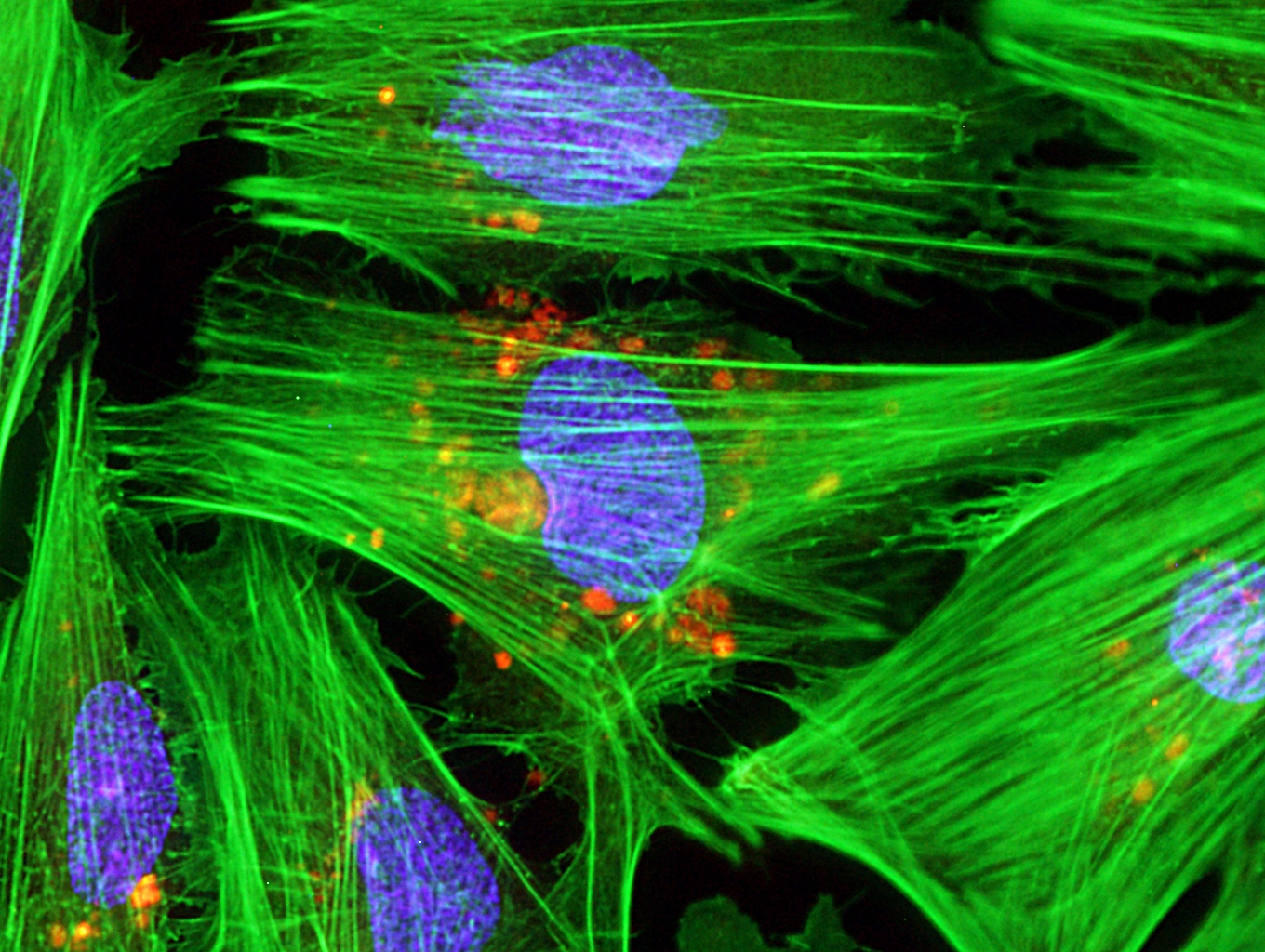

Caption: Micrograph of laboratory-grown rat heart muscle cells. Fluorescent labeling shows mitochondria (red), cytoskeleton (green), and nuclei (blue).

Credit: Credit: Douglas B. Cowan and James D. McCully, Harvard Medical School, Boston

This may not look like your average Valentine’s Day card, but it’s an image sure to warm the hearts of many doctors and patients. Why? This micrograph, a winner in the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology’s 2013 BioArt Competition, shows cells that have been specially engineered to repair the damage done by heart attacks—which strike more than 700,000 Americans every year.

Working with rat heart muscle cells grown in a lab dish, NIH-supported bioengineers at Harvard Medical School used transplant techniques to boost the number of tiny powerhouses, called mitochondria, within the cells. If you look closely at the image above, you’ll see the heart muscle cells are tagged in green, their nuclei in blue, and their mitochondria in red.

Ancient Drug Meets Personalized Medicine

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

It’s pretty amazing to me that we’re still discovering new uses for a drug as old as aspirin. The active metabolite of aspirin—salicylic acid—has been used to treat ailments for several millennia. In fact, the ancient Egyptians and Greeks even used teas and other potions brewed from the bark of the willow tree, which is rich in salicylic acid, to treat their fevers, headaches, and pains.

Today, as many of you may already know, low-dose aspirin can play a key role preventing heart attacks and strokes; it’s often prescribed as a daily therapy for people who’ve suffered a heart attack or are at high risk of one. But it doesn’t stop there. Scientists are now exploring whether this pharmaceutical multitasker can also suppress cancer.

In recent trials, researchers have been testing aspirin for people with colon or colorectal cancer, the third most deadly cancer in the United States. However, they weren’t sure who would benefit. Recently, NIH-supported researchers based in Boston showed that taking aspirin boosted survival among patients diagnosed with colon cancer. But here’s the 21st century catch: the aspirin only had an impact in the 15-20% of patients whose tumors carried a mutation in the PIK3CA gene. (Note: This is not a mutation we inherit from our parents, it is a harmful mutation that arises spontaneously in tumors during the course of cancer development.)