inflammation

Understanding Childbirth Through a Single-Cell Atlas of the Placenta

Posted on by Dr. Monica M. Bertagnolli

While every birth story is unique, many parents would agree that going into labor is an unpredictable process. Although most pregnancies last about 40 weeks, about one in every 10 infants in the U.S. are born before the 37th week of pregnancy, when their brain, lungs, and liver are still developing.1 Some pregnancies also end in an unplanned emergency caesarean delivery after labor fails to progress, for reasons that are largely unknown. Gaining a better understanding of what happens during healthy labor at term may help to elucidate why labor doesn’t proceed normally in some cases.

In a recent development, NIH scientists and their colleagues reported some fascinating new findings that could one day give healthcare providers the tools to better understand and perhaps even predict labor.2 The research team produced an atlas showing the patterns of gene activity that take place in various cell types during labor. To create the atlas, they examined tissues from the placentas of 18 patients not in labor who underwent caesarean delivery and 24 patients in labor. The researchers also analyzed blood samples from another cohort of more than 250 people who delivered at various timepoints. This remarkable study, published in Science Translational Medicine, is the first to analyze gene activity at the single-cell level to better understand the communication that occurs between maternal and fetal cells and tissues during labor.

The placenta is an essential organ for bringing nutrients and oxygen to a growing fetus. It also removes waste, provides immune protection, and supports fetal development. The placenta participates in the process of normal labor at term and preterm labor. Problems with the placenta can lead to many issues, including preterm birth. To create the placental atlas, the study team used an approach called single-cell RNA sequencing. Messenger RNA molecules transcribed or copied from DNA serve as templates for proteins, including those that send important signals between tissues. By sequencing RNAs at the single-cell level, it’s possible to examine gene activity and signaling patterns in many thousands of individual cells at once. This method allows scientists to capture and describe in detail the activities within individual cell types along with interactions among cells of different types and in immune or other key signaling pathways.

Using this approach, the researchers found that cells in the chorioamniotic membranes, which surround the fetus and rupture as part of the labor and delivery process, showed the greatest changes. They also found cells in the mother and fetus that were especially active in generating inflammatory signals. They note that these findings are consistent with previous research showing that inflammation plays an important role in sustaining labor.

Gene activity patterns and changes in the placenta can only be studied after the placenta is delivered. However, it would be ideal if these changes could be identified in the bloodstream of mothers earlier in pregnancy—before labor—so that health care providers can intervene if necessary. The recent study showed that this was possible: Certain gene activity patterns observed in placental cells during labor could be detected in blood tests of women earlier in pregnancy who would later go on to have a preterm birth. The authors note that more research is needed to validate these findings before they can be used as a clinical tool.

Overall, these findings offer important insight into the underlying biology that normally facilitates healthy labor and delivery. They also offer preliminary proof-of-concept evidence that placental biomarkers present in the bloodstream during pregnancy may help to identify pregnancies at increased risk for preterm birth. While much more work and larger studies are needed, these findings suggest that it may one day be possible to identify those at risk for a difficult or untimely labor, when there is still opportunity to intervene.

The research was conducted by the Pregnancy Research Branch part of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), and led by Roberto Romero, M.D., D.Med.Sci., NICHD; Nardhy Gomez-Lopez, Ph.D., Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis; and Roger Pique-Regi, Ph.D., Wayne State University, Detroit.

References:

[1] Preterm Birth. CDC.

[2] Garcia-Flores V, et al., Deciphering maternal-fetal crosstalk in the human placenta during parturition using single-cell RNA sequencing. Science Translational Medicine DOI: 10.1126/scitranslmed.adh8335 (2024).

NIH Support: Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development

Findings in Tuberculosis Immunity Point Toward New Approaches to Treatment and Prevention

Posted on by Dr. Monica M. Bertagnolli

Tuberculosis, caused by the bacteria Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), took 1.3 million lives in 2022, making it the second leading infectious killer around the world after COVID-19, according to the World Health Organization. Current TB treatments require months of daily medicine, and certain cases of TB are becoming increasingly difficult to treat because of drug resistance. While TB case counts had been steadily decreasing before the COVID-19 pandemic, there’s been an uptick in the last couple of years.

Although a TB vaccine exists and offers some protection to young children, the vaccine, known as BCG, has not effectively prevented TB in adults. Developing more protective and longer lasting TB vaccines remains an urgent priority for NIH. As part of this effort, NIH’s Immune Mechanisms of Protection Against Mycobacterium tuberculosis Centers (IMPAc-TB) are working to learn more about how we can harness our immune systems to mount the best protection against Mtb. And I’m happy to share some encouraging results now reported in the journal PLoS Pathogens, which show progress in understanding TB immunity and suggest additional strategies to fight this deadly bacterial infection in the future.1

Most vaccines work by stimulating our immune systems to produce antibodies that target a specific pathogen. The antibodies work to protect us from getting sick if we are ever exposed to that pathogen in the future. However, the body’s more immediate but less specific response against infection, called the innate immune system, serves as the first line of defense. The innate immune system includes cells known as macrophages that gobble up and destroy pathogens while helping to launch inflammatory responses that help you fight an infection.

In the case of TB, here’s how it works: If you were to inhale Mtb bacteria into your lungs, macrophages in tiny air sacs called alveoli would be the first to encounter it. When these alveolar macrophages meet Mtb for the first time, they don’t mount a strong attack against them. In fact, Mtb can infect these immune macrophages to produce more bacteria for a week or more.

What this intriguing new study led by Alissa Rothchild at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and colleagues from Seattle Children’s Research Institute suggests is that vaccines could target this innate immune response to change the way macrophages in the lungs respond and bolster overall defenses. How would it work? While scientists are just beginning to understand it, it turns out that the adaptive immune system isn’t the only part of our immune system that’s capable of adapting. The innate immune system also can undergo long-term changes, or remodeling, based on its experiences. In the new study, the researchers wanted to explore the various ways alveolar macrophages could respond to Mtb.

In search of ways to do it, the study’s first author, Dat Mai at Seattle Children’s Research Institute, conducted studies in mice. The first group of mice received the BCG vaccine. In the second model, the researchers put Mtb into the ears of mice to cause a persistent but contained infection in their lymph nodes. They’d earlier shown that this contained Mtb infection affords animals some protection against subsequent Mtb infections. A third group of mice—the control group—did not receive any intervention. Weeks later, all three groups of mice were exposed to aerosol Mtb infection under controlled conditions. The researchers then sorted infected macrophages from their lungs for further study.

Alveolar macrophages from the first two sets of mice showed a strong inflammatory response to subsequent Mtb exposure. However, those responses differed: The macrophages from vaccinated mice turned on one type of inflammatory program, while macrophages from mice exposed to the bacteria itself turned on another type. Further study showed that the different exposure scenarios led to other discernable differences in the macrophages that now warrant further study.

The findings show that macrophages can respond significantly differently to the same exposure based on what has happened in the past. They complement earlier findings that BCG vaccination can also lead to long-term effects on other subsets of innate immune cells, including myeloid cells from bone marrow.2,3 The researchers suggest there may be ways to take advantage of such changes to devise new strategies for preventing or treating TB by strengthening not just the adaptive immune response but the innate immune response as well.

As part of the IMPAc-TB Center led by Kevin Urdahl at Seattle Children’s Research Institute, the researchers are now working with Gerhard Walzl and Nelita du Plessis at Stellenbosch University in South Africa to compare the responses in mice to those in human alveolar macrophages collected from individuals across the spectrum of TB disease. As they and others continue to learn more about TB immunity, the hope is to apply these insights toward the development of new vaccines that could combat this disease more effectively and ultimately save lives.

References:

[1] Mai D, et al. Exposure to Mycobacterium remodels alveolar macrophages and the early innate response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. PLoS Pathogens. DOI: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1011871. (2024).

[2] Kaufmann E, et al. BCG Educates Hematopoietic Stem Cells to Generate Protective Innate Immunity against Tuberculosis. Cell. DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.12.031 (2018).

[3] Lange C, et al. 100 years of Mycobacterium bovis bacille Calmette-Guérin. Lancet Infectious Diseases. DOI: 10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00403-5. (2022).

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

An Inflammatory View of Early Alzheimer’s Disease

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

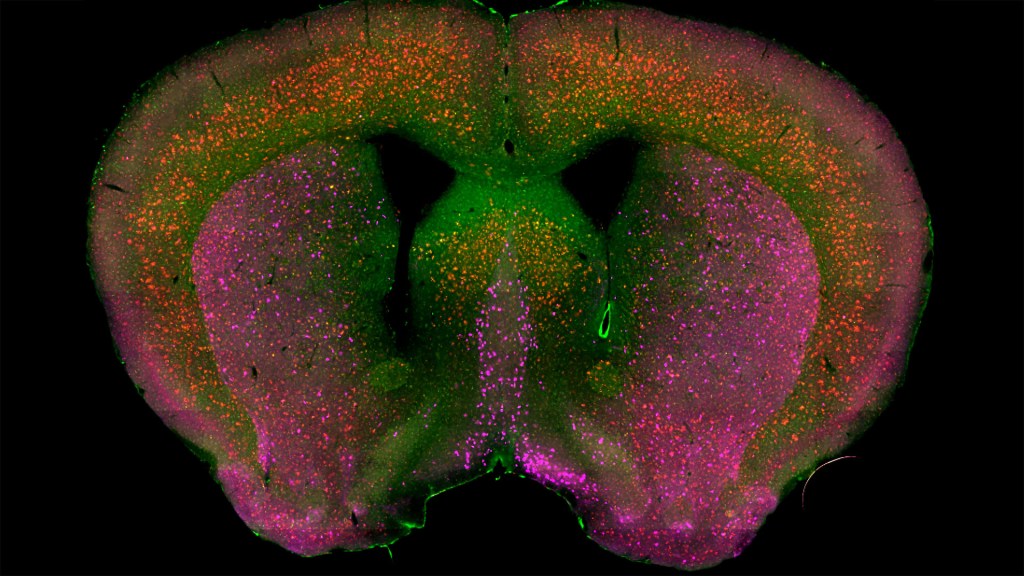

Detecting the earliest signs of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) in middle-aged people and tracking its progression over time in research studies continue to be challenging. But it is easier to do in shorter-lived mammalian models of AD, especially when paired with cutting-edge imaging tools that look across different regions of the brain. These tools can help basic researchers detect telltale early changes that might point the way to better prevention or treatment strategies in humans.

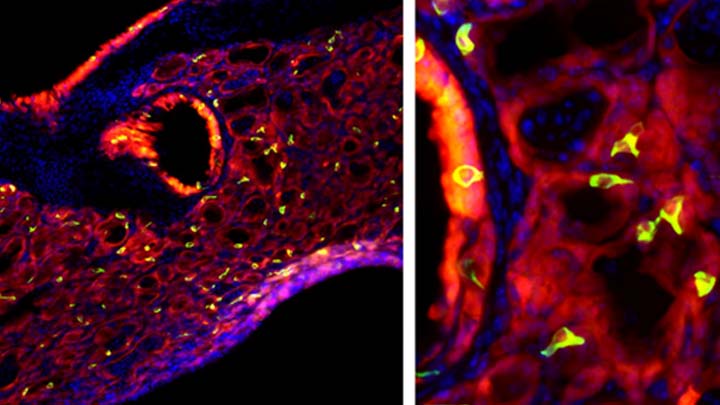

That’s the case in this technicolor snapshot showing early patterns of inflammation in the brain of a relatively young mouse bred to develop a condition similar to AD. You can see abnormally high levels of inflammation throughout the front part of the brain (orange, green) as well as in its middle part—the septum that divides the brain’s two sides. This level of inflammation suggests that the brain has been injured.

What’s striking is that no inflammation is detectable in parts of the brain rich in cholinergic neurons (pink), a distinct type of nerve cell that helps to control memory, movement, and attention. Though these neurons still remain healthy, researchers would like to know if the inflammation also will destroy them as AD progresses.

This colorful image comes from medical student Sakar Budhathoki, who earlier worked in the NIH labs of Lorna Role and David Talmage, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS). Budhathoki, teaming with postdoctoral scientist Mala Ananth, used a specially designed wide-field scanner that sweeps across brain tissue to light up fluorescent markers and capture the image. It’s one of the scanning approaches pioneered in the Role and Talmage labs [1,2].

The two NIH labs are exploring possible links between abnormal inflammation and damage to the brain’s cholinergic signaling system. In fact, medications that target cholinergic function remain the first line of treatment for people with AD and other dementias. And yet, researchers still haven’t adequately determined when, why, and how the loss of these cholinergic neurons relates to AD.

It’s a rich area of basic research that offers hope for greater understanding of AD in the future. It’s also the source of some fascinating images like this one, which was part of the 2022 Show Us Your BRAIN! Photo and Video Contest, supported by NIH’s Brain Research Through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies® (BRAIN) Initiative.

References:

[1] NeuRegenerate: A framework for visualizing neurodegeneration. Boorboor S, Mathew S, Ananth M, Talmage D, Role LW, Kaufman AE. IEEE Trans Vis Comput Graph. 2021;Nov 10;PP.

[2] NeuroConstruct: 3D reconstruction and visualization of neurites in optical microscopy brain images. Ghahremani P, Boorboor S, Mirhosseini P, Gudisagar C, Ananth M, Talmage D, Role LW, Kaufman AE. IEEE Trans Vis Comput Graph. 2022 Dec;28(12):4951-4965.

Links:

Alzheimer’s Disease & Related Dementias (National Institute on Aging/NIH)

Role Lab (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke/NIH)

Talmage Lab (NINDS)

The Brain Research Through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies® (BRAIN) Initiative (NIH)

Show Us Your BRAINs! Photo and Video Contest (BRAIN Initiative)

NIH Support: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

Can Autoimmune Antibodies Explain Blood Clots in COVID-19?

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

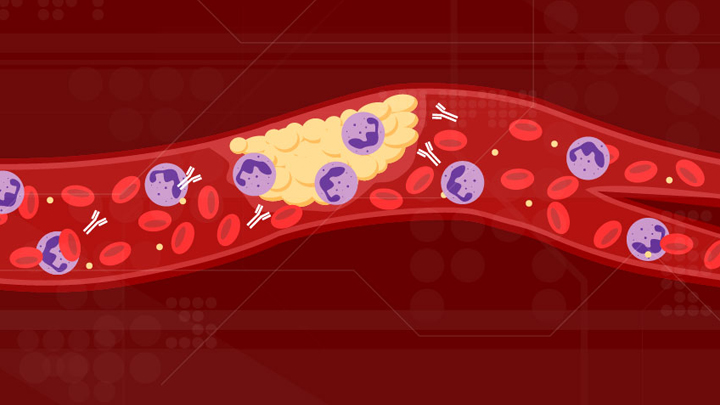

For people with severe COVID-19, one of the most troubling complications is abnormal blood clotting that puts them at risk of having a debilitating stroke or heart attack. A new study suggests that SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, doesn’t act alone in causing blood clots. The virus seems to unleash mysterious antibodies that mistakenly attack the body’s own cells to cause clots.

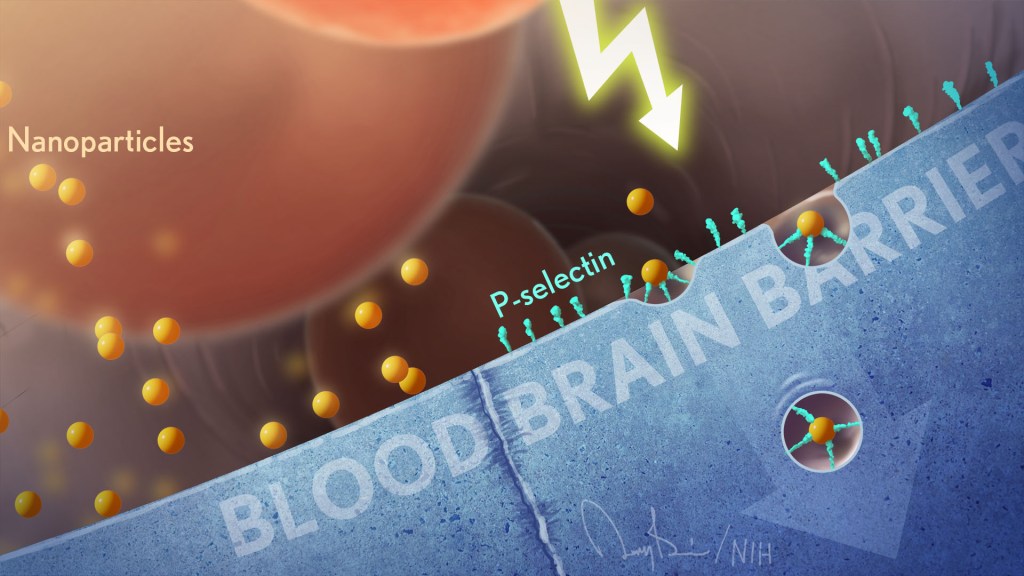

The NIH-supported study, published in Science Translational Medicine, uncovered at least one of these autoimmune antiphospholipid (aPL) antibodies in about half of blood samples taken from 172 patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Those with higher levels of the destructive autoantibodies also had other signs of trouble. They included greater numbers of sticky, clot-promoting platelets and NETs, webs of DNA and protein that immune cells called neutrophils spew to ensnare viruses during uncontrolled infections, but which can lead to inflammation and clotting. These observations, coupled with the results of lab and mouse studies, suggest that treatments to control those autoantibodies may hold promise for preventing the cascade of events that produce clots in people with COVID-19.

Our blood vessels normally strike a balance between producing clotting and anti-clotting factors. This balance keeps us ready to seal up vessels after injury, but otherwise to keep our blood flowing at just the right consistency so that neutrophils and platelets don’t stick and form clots at the wrong time. But previous studies have suggested that SARS-CoV-2 can tip the balance toward promoting clot formation, raising questions about which factors also get activated to further drive this dangerous imbalance.

To learn more, a team of physician-scientists, led by Yogendra Kanthi, a newly recruited Lasker Scholar at NIH’s National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and his University of Michigan colleague Jason S. Knight, looked to various types of aPL autoantibodies. These autoantibodies are a major focus in the Knight Lab’s studies of an acquired autoimmune clotting condition called antiphospholipid syndrome. In people with this syndrome, aPL autoantibodies attack phospholipids on the surface of cells including those that line blood vessels, leading to increased clotting. This syndrome is more common in people with other autoimmune or rheumatic conditions, such as lupus.

It’s also known that viral infections, including COVID-19, produce a transient increase in aPL antibodies. The researchers wondered whether those usually short-lived aPL antibodies in COVID-19 could trigger a condition similar to antiphospholipid syndrome.

The researchers showed that’s exactly the case. In lab studies, neutrophils from healthy people released twice as many NETs when cultured with autoantibodies from patients with COVID-19. That’s remarkably similar to what had been seen previously in such studies of the autoantibodies from patients with established antiphospholipid syndrome. Importantly, their studies in the lab further suggest that the drug dipyridamole, used for decades to prevent blood clots, may help to block that antibody-triggered release of NETs in COVID-19.

The researchers also used mouse models to confirm that autoantibodies from patients with COVID-19 actually led to blood clots. Again, those findings closely mirror what happens in mouse studies testing the effects of antibodies from patients with the most severe forms of antiphospholipid syndrome.

While more study is needed, the findings suggest that treatments directed at autoantibodies to limit the formation of NETs might improve outcomes for people severely ill with COVID-19. The researchers note that further study is needed to determine what triggers autoantibodies in the first place and how long they last in those who’ve recovered from COVID-19.

The researchers have already begun enrolling patients into a modest scale clinical trial to test the anti-clotting drug dipyridamole in patients who are hospitalized with COVID-19, to find out if it can protect against dangerous blood clots. These observations may also influence the design of the ACTIV-4 trial, which is testing various antithrombotic agents in outpatients, inpatients, and convalescent patients. Kanthi and Knight suggest it may also prove useful to test infected patients for aPL antibodies to help identify and improve treatment for those who may be at especially high risk for developing clots. The hope is this line of inquiry ultimately will lead to new approaches for avoiding this very troubling complication in patients with severe COVID-19.

Reference:

[1] Prothrombotic autoantibodies in serum from patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Zuo Y, Estes SK, Ali RA, Gandhi AA, Yalavarthi S, Shi H, Sule G, Gockman K, Madison JA, Zuo M, Yadav V, Wang J, Woodard W, Lezak SP, Lugogo NL, Smith SA, Morrissey JH, Kanthi Y, Knight JS. Sci Transl Med. 2020 Nov 2:eabd3876.

Links:

Coronavirus (COVID-19) (NIH)

Antiphospholipid Antibody Syndrome (National Heart Lung and Blood Institute/NIH)

Kanthi Lab (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Bethesda, MD)

Knight Lab (University of Michigan)

ACTIV (NIH)

NIH Support: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

See the Human Cardiovascular System in a Whole New Way

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Watch this brief video and you might guess you’re seeing an animated line drawing, gradually revealing a delicate take on a familiar system: the internal structures of the human body. But this movie doesn’t capture the work of a talented sketch artist. It was created using the first 3D, full-body imaging device using positron emission tomography (PET).

The device is called an EXPLORER (EXtreme Performance LOng axial REsearch scanneR) total-body PET scanner. By pairing this scanner with an advanced method for reconstructing images from vast quantities of data, the researchers can make movies.

For this movie in particular, the researchers injected small amounts of a short-lived radioactive tracer—an essential component of all PET scans—into the lower leg of a study volunteer. They then sat back as the scanner captured images of the tracer moving up the leg and into the body, where it enters the heart. The tracer moves through the heart’s right ventricle to the lungs, back through the left ventricle, and up to the brain. Keep watching, and, near the 30-second mark, you will see in closer focus a haunting capture of the beating heart.

This groundbreaking scanner was developed and tested by Jinyi Qi, Simon Cherry, Ramsey Badawi, and their colleagues at the University of California, Davis [1]. As the NIH-funded researchers reported recently in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, their new scanner can capture dynamic changes in the body that take place in a tenth of a second [2]. That’s faster than the blink of an eye!

This movie is composed of frames captured at 0.1-second intervals. It highlights a feature that makes this scanner so unique: its ability to visualize the whole body at once. Other medical imaging methods, including MRI, CT, and traditional PET scans, can be used to capture beautiful images of the heart or the brain, for example. But they can’t show what’s happening in the heart and brain at the same time.

The ability to capture the dynamics of radioactive tracers in multiple organs at once opens a new window into human biology. For example, the EXPLORER system makes it possible to measure inflammation that occurs in many parts of the body after a heart attack, as well as to study interactions between the brain and gut in Parkinson’s disease and other disorders.

EXPLORER also offers other advantages. It’s extra sensitive, which enables it to capture images other scanners would miss—and with a lower dose of radiation. It’s also much faster than a regular PET scanner, making it especially useful for imaging wiggly kids. And it expands the realm of research possibilities for PET imaging studies. For instance, researchers might repeatedly image a person with arthritis over time to observe changes that may be related to treatments or exercise.

Currently, the UC Davis team is working with colleagues at the University of California, San Francisco to use EXPLORER to enhance our understanding of HIV infection. Their preliminary findings show that the scanner makes it easier to capture where the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), the cause of AIDS, is lurking in the body by picking up on signals too weak to be seen on traditional PET scans.

While the research potential for this scanner is clearly vast, it also holds promise for clinical use. In fact, a commercial version of the scanner, called uEXPLORER, has been approved by the FDA and is in use at UC Davis [3]. The researchers have found that its improved sensitivity makes it much easier to detect cancers in patients who are obese and, therefore, harder to image well using traditional PET scanners.

As soon as the COVID-19 outbreak subsides enough to allow clinical research to resume, the researchers say they’ll begin recruiting patients with cancer into a clinical study designed to compare traditional PET and EXPLORER scans directly.

As these researchers, and other researchers around the world, begin to put this new scanner to use, we can look forward to seeing many more remarkable movies like this one. Imagine what they will reveal!

References:

[1] First human imaging studies with the EXPLORER total-body PET scanner. Badawi RD, Shi H, Hu P, Chen S, Xu T, Price PM, Ding Y, Spencer BA, Nardo L, Liu W, Bao J, Jones T, Li H, Cherry SR. J Nucl Med. 2019 Mar;60(3):299-303.

[2] Subsecond total-body imaging using ultrasensitive positron emission tomography. Zhang X, Cherry SR, Xie Z, Shi H, Badawi RD, Qi J. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020 Feb 4;117(5):2265-2267.

[3] “United Imaging Healthcare uEXPLORER Total-body Scanner Cleared by FDA, Available in U.S. Early 2019.” Cision PR Newswire. January 22, 2019.

Links:

Positron Emission Tomography (PET) (NIH Clinical Center)

EXPLORER Total-Body PET Scanner (University of California, Davis)

Cherry Lab (UC Davis)

Badawi Lab (UC Davis Medical Center, Sacramento)

NIH Support: National Cancer Institute; National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering; Common Fund

These Oddball Cells May Explain How Influenza Leads to Asthma

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Most people who get the flu bounce right back in a week or two. But, for others, the respiratory infection is the beginning of lasting asthma-like symptoms. Though I had a flu shot, I had a pretty bad respiratory illness last fall, and since that time I’ve had exercise-induced asthma that has occasionally required an inhaler for treatment. What’s going on? An NIH-funded team now has evidence from mouse studies that such long-term consequences stem in part from a surprising source: previously unknown lung cells closely resembling those found in taste buds.

The image above shows the lungs of a mouse after a severe case of H1N1 influenza infection, a common type of seasonal flu. Notice the oddball cells (green) known as solitary chemosensory cells (SCCs). Those little-known cells display the very same chemical-sensing surface proteins found on the tongue, where they allow us to sense bitterness. What makes these images so interesting is, prior to infection, the healthy mouse lungs had no SCCs.

SCCs, sometimes called “tuft cells” or “brush cells” or “type II taste receptor cells”, were first described in the 1920s when a scientist noticed unusual looking cells in the intestinal lining [1] Over the years, such cells turned up in the epithelial linings of many parts of the body, including the pancreas, gallbladder, and nasal passages. Only much more recently did scientists realize that those cells were all essentially the same cell type. Owing to their sensory abilities, these epithelial cells act as a kind of lookout for signs of infection or injury.

This latest work on SCCs, published recently in the American Journal of Physiology–Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology, adds to this understanding. It comes from a research team led by Andrew Vaughan, University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine, Philadelphia [2].

As a post-doc, Vaughan and colleagues had discovered a new class of cells, called lineage-negative epithelial progenitors, that are involved in abnormal remodeling and regrowth of lung tissue after a serious respiratory infection [3]. Upon closer inspection, they noticed that the remodeling of lung tissue post-infection often was accompanied by sustained inflammation. What they didn’t know was why.

The team, including Noam Cohen of Penn’s Perelman School of Medicine and De’Broski Herbert, also of Penn Vet, noticed signs of an inflammatory immune response several weeks after an influenza infection. Such a response in other parts of the body is often associated with allergies and asthma. All were known to involve SCCs, and this begged the question: were SCCs also present in the lungs?

Further work showed not only were SCCs present in the lungs post-infection, they were interspersed across the tissue lining. When the researchers exposed the animals’ lungs to bitter compounds, the activated SCCs multiplied and triggered acute inflammation.

Vaughan’s team also found out something pretty cool. The SCCs arise from the very same lineage of epithelial progenitor cells that Vaughan had discovered as a post-doc. These progenitor cells produce cells involved in remodeling and repair of lung tissue after a serious lung infection.

Of course, mice aren’t people. The researchers now plan to look in human lung samples to confirm the presence of these cells following respiratory infections.

If confirmed, the new findings might help to explain why kids who acquire severe respiratory infections early in life are at greater risk of developing asthma. They suggest that treatments designed to control these SCCs might help to treat or perhaps even prevent lifelong respiratory problems. The hope is that ultimately it will help to keep more people breathing easier after a severe bout with the flu.

References:

[1] Closing in on a century-old mystery, scientists are figuring out what the body’s ‘tuft cells’ do. Leslie M. Science. 2019 Mar 28.

[2] Development of solitary chemosensory cells in the distal lung after severe influenza injury. Rane CK, Jackson SR, Pastore CF, Zhao G, Weiner AI, Patel NN, Herbert DR, Cohen NA, Vaughan AE. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2019 Mar 25.

[3] Lineage-negative progenitors mobilize to regenerate lung epithelium after major injury. Vaughan AE, Brumwell AN, Xi Y, Gotts JE, Brownfield DG, Treutlein B, Tan K, Tan V, Liu FC, Looney MR, Matthay MA, Rock JR, Chapman HA. Nature. 2015 Jan 29;517(7536):621-625.

Links:

Asthma (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/NIH)

Influenza (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases/NIH)

Vaughan Lab (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia)

Cohen Lab (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia)

Herbert Lab (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia)

NIH Support: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders

Creative Minds: Giving Bacteria Needles to Fight Intestinal Disease

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

For Salmonella and many other disease-causing bacteria that find their way into our bodies, infection begins with a poke. That’s because these bad bugs are equipped with a needle-like protein filament that punctures the outer membrane of human cells and then, like a syringe, injects dozens of toxic proteins that help them replicate.

Cammie Lesser at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Cambridge, and her colleagues are now on a mission to bioengineer strains of bacteria that don’t cause disease to make these same syringes, called type III secretion systems. The goal is to use such “good” bacteria to deliver therapeutic molecules, rather than toxins, to human cells. Their first target is the gastrointestinal tract, where they hope to knock out hard-to-beat bacterial infections or to relieve the chronic inflammation that comes with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

Next Page