bacteria

Fundamental Knowledge of Microbes Shedding New Light on Human Health

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Basic research in biology generates fundamental knowledge about the nature and behavior of living systems. It is generally impossible to predict exactly where this line of scientific inquiry might lead, but history shows that basic science almost always serves as the foundation for dramatic breakthroughs that advance human health. Indeed, many important medical advances can be traced back to basic research that, at least at the outset, had no clear link at all to human health.

One exciting example of NIH-supported basic research is the Human Microbiome Project (HMP), which began 12 years ago as a quest to use DNA sequencing to identify and characterize the diverse collection of microbes—including trillions of bacteria, fungi, and viruses—that live on and in the healthy human body.

The HMP researchers have subsequently been using those vast troves of fundamental data as a tool to explore how microbial communities interact with human cells to influence health and disease. Today, these explorers are reporting their latest findings in a landmark set of papers in the Nature family of journals. Among other things, these findings shed new light on the microbiome’s role in prediabetes, inflammatory bowel disease, and preterm birth. The studies are part of the Integrative Human Microbiome Project.

If you’d like to keep up on the microbiome and other basic research journeys, here’s a good way to do so. Consider signing up for basic research updates from the NIH Director’s Blog and NIH Research Matters. Here’s how to do it: Go to Email Updates, type in your email address, and enter. That’s it. If you’d like to see other update possibilities, including clinical and translational research, hit the “Finish” button to access Subscriber Preferences.

As for the recent microbiome findings, let’s start with the prediabetes study [1]. An estimated 1 in 3 American adults has prediabetes, detected by the presence of higher than normal fasting blood glucose levels. If uncontrolled and untreated, prediabetes can lead to the more-severe type 2 diabetes (T2D) and its many potentially serious side effects [2].

George Weinstock, The Jackson Laboratory for Genomic Medicine, Farmington, CT, Michael Snyder, Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA, and colleagues report that they have assembled a rich new data set covering the complex biology of prediabetes. That includes a comprehensive analysis of the human microbiome in prediabetes.

The data come from monitoring the health of 106 people with and without prediabetes for nearly four years. The researchers met with participants every three months, drawing blood, assessing the gut microbiome, and performing 51 laboratory tests. All this work generated millions of molecular and microbial measurements that provided a unique biological picture of prediabetes.

The picture showed specific interactions between cells and microbes that were different for people who are sensitive to insulin and those whose cells are resistant to it (as is true of many of those with prediabetes). The data also pointed to extensive changes in the microbiome during respiratory viral infections. Those changes showed clear differences in people with and without prediabetes. Some aspects of the immune response also appeared abnormal in people who were prediabetic.

As demonstrated in a landmark NIH study several years ago [2], people with prediabetes can do a lot to reduce their chances of developing T2D, such as exercising, eating healthy, and losing a modest amount of body weight. But this study offers some new leads to define the biological underpinnings of T2D in its earliest stages. These insights potentially point to high value targets for slowing or perhaps stopping the systemic changes that drive the transition from prediabetes to T2D.

The second study features the work of the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Multi’omics Data team. It’s led by Ramnik Xavier and Curtis Huttenhower, Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, MA. [4]

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is an umbrella term for chronic inflammations of the body’s digestive tract, such as Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. These disorders are characterized by remissions and relapses, and the most severe flares can be life-threatening. Xavier, Huttenhower, and team followed 132 people with and without IBD for a year, collecting samples of their gut microbiomes every other week along with biopsies and blood samples for a total of nearly 3,000 samples.

By integrating DNA, RNA, protein, and metabolic analyses, they followed precisely which microbial species were present. They could also track which biochemical functions those microbes were capable of performing, and which functions they actually were performing over the course of the study.

These data now offer the most comprehensive view yet of functional imbalances associated with changes in the microbiome during IBD flares. These data also show how those imbalances may be altered when a person with IBD goes into remission. It’s also noteworthy that participants completed questionnaires on their diet. This dataset is the first to capture associations between diet and the gut microbiome in a relatively large group of people over time.

The evidence showed that the gut microbiomes of people with IBD were significantly less stable than the microbiomes of those without IBD. During IBD activity, the researchers observed increases in certain groups of microbes at the expense of others. Those changes in the microbiome also came with other telltale metabolic and biochemical disruptions along with shifts in the functioning of an individual’s immune system. The shifts, however, were not significantly associated with people taking medications or their social status.

By presenting this comprehensive, “multi-omic” view on the microbiome in IBD, the researchers were able to single out a variety of new host and microbial features that now warrant further study. For example, people with IBD had dramatically lower levels of an unclassified Subdoligranulum species of bacteria compared to people without the condition.

The third study features the work of The Vaginal Microbiome Consortium (VMC). The study represents a collaboration between Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, and Global Alliance to Prevent Prematurity and Stillbirth (GAPPS). The VMC study is led by Gregory Buck, Jennifer Fettweis, Jerome Strauss,and Kimberly Jefferson of Virginia Commonwealth and colleagues.

In this study, part of the Multi-Omic Microbiome Study: Pregnancy Initiative, the team followed up on previous research that suggested a potential link between the composition of the vaginal microbiome and the risk of preterm birth [5]. The team collected various samples from more than 1,500 pregnant women at multiple time points in their pregnancies. The researchers sequenced the complete microbiomes from the vaginal samples of 45 study participants, who gave birth prematurely and 90 case-matched controls who gave birth to full-term babies. Both cases and controls were primarily of African ancestry.

Those data reveal unique microbial signatures early in pregnancy in women who went on to experience a preterm birth. Specifically, women who delivered their babies earlier showed lower levels of Lactobacillus crispatus, a bacterium long associated with health in the female reproductive tract. Those women also had higher levels of several other microbes. The preterm birth-associated signatures also were associated with other inflammatory molecules.

The findings suggest a link between the vaginal microbiome and preterm birth, and raise the possibility that a microbiome test, conducted early in pregnancy, might help to predict a woman’s risk for preterm birth. Even more exciting, this might suggest a possible way to modify the vaginal microbiome to reduce the risk of prematurity in susceptible individuals.

Overall, these landmark HMP studies add to evidence that our microbial inhabitants have important implications for many aspects of our health. We are truly a “superorganism.” In terms of the implications for biomedicine, this is still just the beginning of what is sure to be a very exciting journey.

References:

[1] Longitudinal multi-omics of host-microbe dynamics in prediabetes. Zhou W, Sailani MR, Contrepois K, Sodergren E, Weinstock GM, Snyder M, et. al. Nature. 2019 May 29.

[2] National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2017, Center for Disease Control and Prevention (Atlanta, GA)

[3] Long-term effects of lifestyle intervention or metformin on diabetes development and microvascular complications over 15-year follow-up: the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group.Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol.2015 Nov;3(11):866-875.

[4] Multi-omics of the gut microbial ecosystem in inflammatory bowel disease. Lloyd-Price J, Arze C. Ananthakrishnan AN, Vlamakis H, Xavier RJ, Huttenhower C, et. al. Nature. 2019 May 29.

[5] The vaginal microbiome and preterm birth. Fettweis JM, Serrano MG, Brooks, JP, Jefferson KK, Strauss JF, Buck GA, et al. Nature Med. 2019 May 29.

Links:

Insulin Resistance & Prediabetes (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases/NIH)

Crohn’s Disease (NIDDK/NIH)

Ulcerative colitis (NIDDK/NIH)

Preterm Labor and Birth: Condition Information (Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development/NIH)

Global Alliance to Prevent Prematurity and Stillbirth (Seattle, WA)

NIH Integrative Human Microbiome Project

NIH Support:

Prediabetes Study: Common Fund; National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research; National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; National Institute of Human Genome Research; National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences

Inflammatory Bowel Disease Study: Common Fund; National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences; National Institute of Human Genome Research; National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research

Preterm Birth Study: Common Fund; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development

Deciphering Another Secret of Life

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

In 1953, Francis Crick famously told the surprised customers at the Eagle and Child pub in London that he and Jim Watson had discovered the secret of life. When NIH’s Marshall Nirenberg and his colleagues cracked the genetic code in 1961, it was called the solution to life’s greatest secret. Similarly, when the complete human genome sequence was revealed for the first time in 2003, commentators (including me) referred to this as the moment where the book of life for humans was revealed. But there are many more secrets of life that still need to be unlocked, including figuring out the biochemical rules of a protein shape-shifting phenomenon called allostery [1].

Among those taking on this ambitious challenge is a recipient of a 2018 NIH Director’s New Innovator Award, Srivatsan Raman of the University of Wisconsin-Madison. If successful, such efforts could revolutionize biology by helping us better understand how allosteric proteins reconfigure themselves in the right shapes at the right times to regulate cell signaling, metabolism, and many other important biological processes.

What exactly is an allosteric protein? Proteins have active, or orthosteric, sites that turn the proteins off or on when specific molecules bind to them. Some proteins also have less obvious regulatory, or allosteric, sites that indirectly affect the proteins’ activity when outside molecules bind to them. In many instances, allosteric binding triggers a change in the shape of the protein.

Allosteric proteins include oxygen-carrying hemoglobin and a variety of enzymes crucial to human health and development. In his work, Raman will start by studying a relatively simple bacterial protein, consisting of less than 200 amino acids, to understand the basics of how allostery works over time and space.

Raman, who is a synthetic biologist, got the idea for this project a few years ago while tinkering in the lab to modify an allosteric protein to bind new molecules. As part of the process, he and his team used a new technology called deep mutational scanning to study the functional consequences of removing individual amino acids from the protein [2].

The screen took them on a wild ride of unexpected functional changes, and a new research opportunity called out to him. He could combine this scanning technology with artificial intelligence and other cutting-edge imaging and computational tools to probe allosteric proteins more systematically in hopes of deciphering the basic molecular rules of allostery.

With the New Innovator Award, Raman’s group will first create a vast number of protein mutants to learn how best to determine the allosteric signaling pathway(s) within a protein. They want to dissect out the properties of each amino acid and determine which connect into a binding site and precisely how those linkages are formed. The researchers also want to know how the amino acids tend to configure into an inactive state and how that structure changes into an active state.

Based on these initial studies, the researchers will take the next step and use their dataset to predict where allosteric pathways are found in individual proteins. They will also try to figure out if allosteric signals are sent in one direction only or whether they can be bidirectional.

The experiments will be challenging, but Raman is confident that they will serve to build a more unified view of how allostery works. In fact, he hopes the data generated—and there will be a massive amount—will reveal novel sites to control or exploit allosteric signaling. Such information will not only expand fundamental biological understanding, but will accelerate efforts to discover new therapies for diseases, such as cancer, in which disruption of allosteric proteins plays a crucial role.

References:

[1] Allostery: an illustrated definition for the ‘second secret of life.’ Fenton AW. Trends Biochem Sci. 2008 Sep;33(9):420-425.

[2] Engineering an allosteric transcription factor to respond to new ligands. Taylor ND, Garruss AS, Moretti R, Chan S, Arbing MA, Cascio D, Rogers JK, Isaacs FJ, Kosuri S, Baker D, Fields S, Church GM, Raman S. Nat Methods. 2016 Feb;13(2):177-183.

Links:

Drug hunters explore allostery’s advantages. Jarvis LM, Chemical & Engineering News. 2019 March 10

Allostery: An Overview of Its History, Concepts, Methods, and Applications. Liu J, Nussinov R. PLoS Comput Biol. 2016 Jun 2;12(6):e1004966.

Srivatsan Raman (University of Wisconsin-Madison)

Raman Project Information (NIH RePORTER)

NIH Director’s New Innovator Award (Common Fund/NIH)

NIH Support: National Institute of General Medical Sciences; Common Fund

Some ‘Hospital-Acquired’ Infections Traced to Patient’s Own Microbiome

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

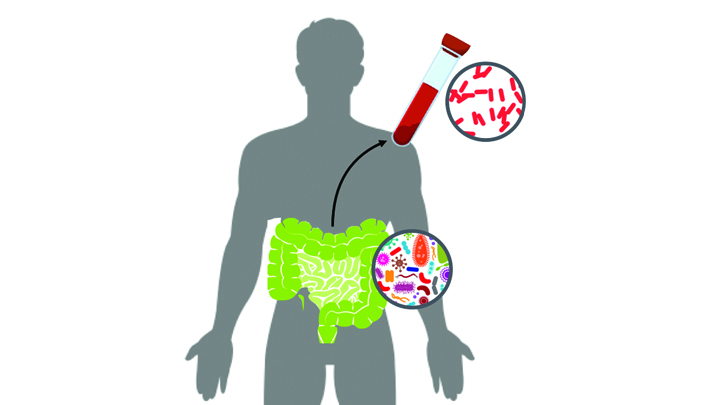

Caption: New computational tool determines whether a gut microbe is the source of a hospital-acquired bloodstream infection

Credit: Fiona Tamburini, Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA

While being cared for in the hospital, a disturbingly large number of people develop potentially life-threatening bloodstream infections. It’s been thought that most of the blame lies with microbes lurking on medical equipment, health-care professionals, or other patients and visitors. And certainly that is often true. But now an NIH-funded team has discovered that a significant fraction of these “hospital-acquired” infections may actually stem from a quite different source: the patient’s own body.

In a study of 30 bone-marrow transplant patients suffering from bloodstream infections, researchers used a newly developed computational tool called StrainSifter to match microbial DNA from close to one-third of the infections to bugs already living in the patients’ large intestines [1]. In contrast, the researchers found little DNA evidence to support the notion that such microbes were being passed around among patients.

A Microbial Work of Art

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: Scott Chimileski, Sylvie Laborde, Nicholas Lyons, Roberto Kolter, Harvard Medical School, Boston

Bacteria are single-celled organisms that are too small to see in detail without the aid of a microscope. So you might not think that zooming in on a batch of bacteria would provide the inspiration for a museum-worthy sculpture.

But, in fact, that’s exactly what you see in the image. Researchers grew in a lab dish Bacillus licheniformis, a usually benign bacterium from the soil that produces an enzyme used in laundry detergent. The bacteria self-organized into a sand dollar-like pattern to form a cohesive structure called a biofilm. The researchers then took a 3D scan of the living bacterial colony in the lab and used it to print this stainless steel sculpture at 12 times the dime-sized biofilm.

A Bacterium Reaches Out and Grabs Some New DNA

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: Dalia Lab, Indiana University, Bloomington

If you like comic book heroes, you’ll love this action-packed video of a microbe with a superpower reminiscent of a miniature Spiderman. Here, for the first time ever, scientists have captured in real-time—and in very cool detail—the important mechanism of horizontal gene transfer in bacteria.

Specifically, you see Vibrio cholerae, the water-dwelling bacterium that causes cholera, stretching out a hair-like appendage called a pilus (green) to snag a free snippet of DNA (red). After grabbing the DNA, V. cholerae swiftly retracts the pilus, threading the DNA fragment through a pore on the cell surface for stitching into its genome.

A Lean, Mean DNA Packaging Machine

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

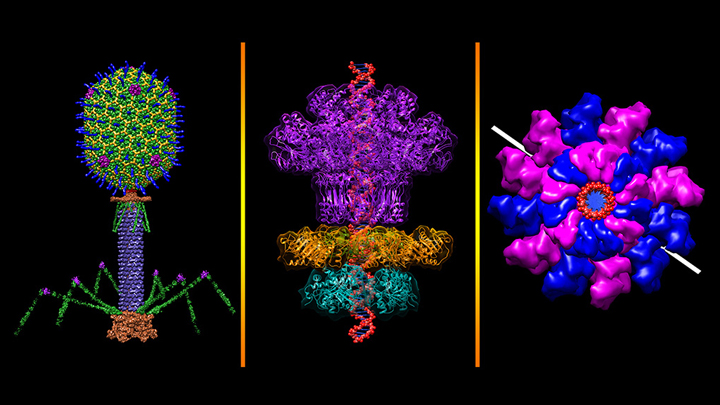

Credit: Victor Padilla-Sanchez, The Catholic University of America, Washington, D.C.

All plants and animals are susceptible to viral infections. But did you know that’s also true for bacteria? They get nailed by viruses called bacteriophages, and there are thousands of them in nature including this one that resembles a lunar lander: bacteriophage T4 (left panel). It’s a popular model organism that researchers have studied for nearly a century, helping them over the years to learn more about biochemistry, genetics, and molecular biology [1].

The bacteriophage T4 infects the bacterium Escherichia coli, which normally inhabits the gastrointestinal tract of humans. T4’s invasion starts by touching down on the bacterial cell wall and injecting viral DNA through its tube-like tail (purple) into the cell. A DNA “packaging machine” (middle and right panels) between the bacteriophage’s “head” and “tail” (green, yellow, blue spikes) keeps the double-stranded DNA (middle panel, red) at the ready. All the vivid colors you see in the images help to distinguish between the various proteins or protein subunits that make up the intricate structure of the bacteriophage and its DNA packaging machine.

Powerful Antibiotics Found in Dirt

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: Researchers found a new class of antibiotics in a collection of about 2,000 soil samples.

Credit: Sean Brady, The Rockefeller University, New York City

Many of us think of soil as lifeless dirt. But, in fact, soil is teeming with a rich array of life: microbial life. And some of those tiny, dirt-dwelling microorganisms—bacteria that produce antibiotic compounds that are highly toxic to other bacteria—may provide us with valuable leads for developing the new drugs we so urgently need to fight antibiotic-resistant infections.

Recently, NIH-funded researchers discovered a new class of antibiotics, called malacidins, by analyzing the DNA of the bacteria living in more than 2,000 soil samples, including many sent by citizen scientists living all across the United States [1]. While more work is needed before malacidins can be tried in humans, the compounds successfully killed several types of multidrug-resistant bacteria in laboratory tests. Most impressive was the ability of malacadins to wipe out methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) skin infections in rats. Often referred to as a “super bug,” MRSA threatens the lives of tens of thousands of Americans each year [2].

Cool Videos: Insulin from Bacteria to You

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

If you have a smartphone, you’ve probably used it to record a video or two. But could you use it to produce a video that explains a complex scientific topic in 2 minutes or less? That was the challenge posed by the RCSB Protein Data Bank last spring to high school students across the nation. And the winning result is the video that you see above!

This year’s contest, which asked students to provide a molecular view of diabetes treatment and management, attracted 53 submissions from schools from coast to coast. The winning team—Andrew Ma, George Song, and Anirudh Srikanth—created their video as their final project for their advanced placement (AP) biology class at West Windsor-Plainsboro High School South, Princeton Junction, NJ.

Previous Page Next Page