bacteria

Creative Minds: Giving Bacteria Needles to Fight Intestinal Disease

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

For Salmonella and many other disease-causing bacteria that find their way into our bodies, infection begins with a poke. That’s because these bad bugs are equipped with a needle-like protein filament that punctures the outer membrane of human cells and then, like a syringe, injects dozens of toxic proteins that help them replicate.

Cammie Lesser at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Cambridge, and her colleagues are now on a mission to bioengineer strains of bacteria that don’t cause disease to make these same syringes, called type III secretion systems. The goal is to use such “good” bacteria to deliver therapeutic molecules, rather than toxins, to human cells. Their first target is the gastrointestinal tract, where they hope to knock out hard-to-beat bacterial infections or to relieve the chronic inflammation that comes with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

Creative Minds: Rapid Testing for Antibiotic Resistance

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Ahmad (Mo) Khalil

The term “freeze-dried” may bring to mind those handy MREs (Meals Ready to Eat) consumed by legions of soldiers, astronauts, and outdoor adventurers. But if one young innovator has his way, a test that features freeze-dried biosensors may soon be a key ally in our nation’s ongoing campaign against the very serious threat of antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections.

Each year, antibiotic-resistant infections account for more than 23,000 deaths in the United States. To help tackle this challenge, Ahmad (Mo) Khalil, a researcher at Boston University, recently received an NIH Director’s New Innovator Award to develop a system that can more quickly determine whether a patient’s bacterial infection will respond best to antibiotic X or antibiotic Y—or, if the infection is actually viral rather than bacterial, no antibiotics are needed at all.

Creative Minds: The Human Gut Microbiome’s Top 100 Hits

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Michael Fishbach

Microbes that live in dirt often engage in their own deadly turf wars, producing a toxic mix of chemical compounds (also called “small molecules”) that can be a source of new antibiotics. When he started out in science more than a decade ago, Michael Fischbach studied these soil-dwelling microbes to look for genes involved in making these compounds.

Eventually, Fischbach, who is now at the University of California, San Francisco, came to a career-altering realization: maybe he didn’t need to dig in dirt! He hypothesized an even better way to improve human health might be found in the genes of the trillions of microorganisms that dwell in and on our bodies, known collectively as the human microbiome.

Fighting Parasitic Infections: Promise in Cyclic Peptides

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: Cyclic peptide (middle) binds to iPGM (blue).

Credit: National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, NIH

When you think of the causes of infectious diseases, what first comes to mind are probably viruses and bacteria. But parasites are another important source of devastating infection, especially in the developing world. Now, NIH researchers and their collaborators have discovered a new kind of treatment that holds promise for fighting parasitic roundworms. A bonus of this result is that this same treatment might work also for certain deadly kinds of bacteria.

The researchers identified the potential new therapeutic after testing more than a trillion small protein fragments, called cyclic peptides, to find one that could disable a vital enzyme in the disease-causing organisms, but leave similar enzymes in humans unscathed. Not only does this discovery raise hope for better treatments for many parasitic and bacterial diseases, it highlights the value of screening peptides in the search for ways to treat conditions that do not respond well—or have stopped responding—to more traditional chemical drug compounds.

Cool Videos: Making Multicolored Waves in Cell Biology

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Bacteria are single-cell organisms that reproduce by dividing in half. Proteins within these cells organize themselves in a number of fascinating ways during this process, including a recently discovered mechanism that makes the mesmerizing pattern of waves, or oscillations, you see in this video. Produced when the protein MinE chases the protein MinD from one end of the cell to the other, such oscillations are thought to center the cell’s division machinery so that its two new “daughter cells” will be the same size.

To study these dynamic patterns in greater detail, Anthony Vecchiarelli purified MinD and MinE proteins from the bacterium Escherichia coli. Vecchiarelli, who at the time was a postdoc in Kiyoshi Mizuuchi’s intramural lab at NIH’s National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), labeled the proteins with fluorescent markers and placed them on a synthetic membrane, where their movements were then visualized by total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy. The proteins self-organized and generated dynamic spirals of waves: MinD (blue, left); MinE (red, right); and both MinD and MinE (purple, center) [1].

Eczema Relief: Probiotic Lotion Shows Early Promise

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

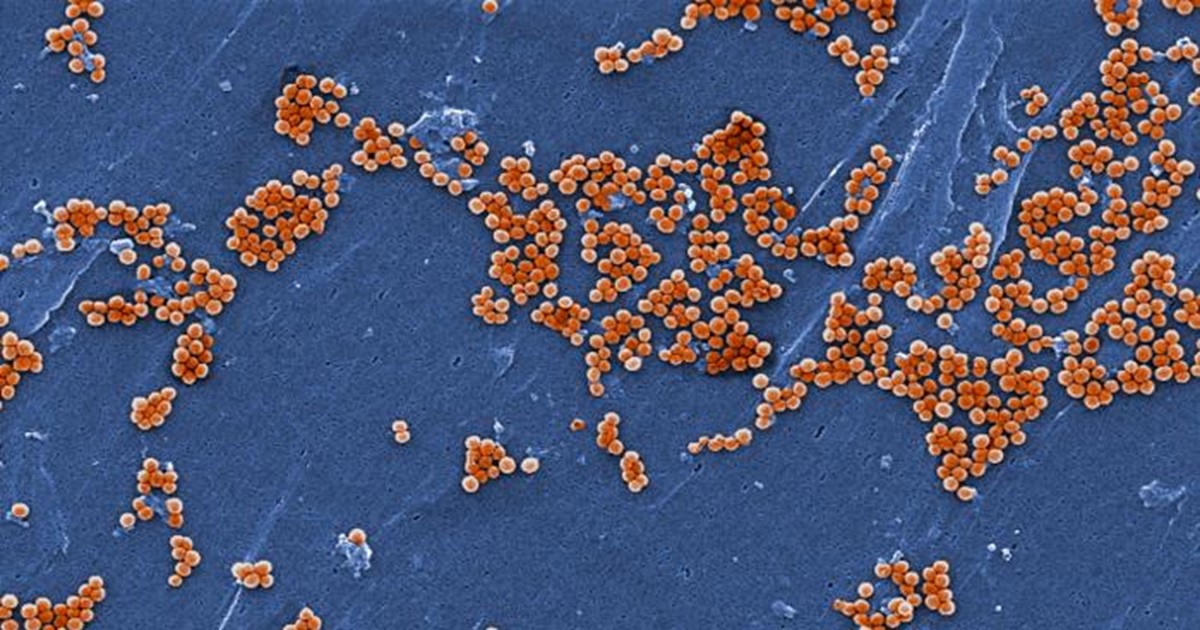

Caption: Scanning electron microscopic image of Staphylococcus aureus bacteria (orange).

Credit: CDC/Jeff Hageman, MHS

Over the years, people suffering from eczema have slathered their skin with lotions containing everything from avocado oil to zinc oxide. So, what about a lotion that features bacteria as the active ingredient? That might seem like the last thing a person with a skin problem would want to do, but it’s actually a very real possibility, based on new findings that build upon the growing realization that many microbes living in and on the human body—our microbiome—are essential for good health. The idea behind such a bacterial lotion is that good bugs can displace bad bugs.

Eczema is a noncontagious inflammatory skin condition characterized by a dry, itchy rash. It most commonly affects the cheeks, arms, and legs. Previous studies have suggested that the balance of microbes present on people with eczema is different than on those with healthy skin [1]. One major difference is a proliferation of a bad type of bacteria, called Staphylococcus aureus.

Recently, an NIH-funded research team found that healthy human skin harbors beneficial strains of Staphylococcus bacteria with the power to keep Staph aureus in check. To see if there might be a way to restore this natural balance artificially, the researchers created a lotion containing the protective bacteria and tested it on the arms of volunteers who had eczema [2]. Just 24 hours after one dose of the lotion was applied, the researchers found the volunteers’ skin had greatly reduced levels of Staph aureus. While further study is needed to learn whether the treatment can improve skin health, the findings suggest that similar lotions might offer a new approach for treating eczema and other skin conditions. Think of it as a probiotic for the skin!

Find and Replace: DNA Editing Tool Shows Gene Therapy Promise

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: This image represents an infection-fighting cell called a neutrophil. In this artist’s rendering, the cell’s DNA is being “edited” to help restore its ability to fight bacterial invaders.

Credit: NIAID, NIH

For gene therapy research, the perennial challenge has been devising a reliable way to insert safely a working copy of a gene into relevant cells that can take over for a faulty one. But with the recent discovery of powerful gene editing tools, the landscape of opportunity is starting to change. Instead of threading the needle through the cell membrane with a bulky gene, researchers are starting to design ways to apply these tools in the nucleus—to edit out the disease-causing error in a gene and allow it to work correctly.

While the research is just getting under way, progress is already being made for a rare inherited immunodeficiency called chronic granulomatous disease (CGD). As published recently in Science Translational Medicine, a team of NIH researchers has shown with the help of the latest CRISPR/Cas9 gene-editing tools, they can correct a mutation in human blood-forming adult stem cells that triggers a common form of CGD. What’s more, they can do it without introducing any new and potentially disease-causing errors to the surrounding DNA sequence [1].

When those edited human cells were transplanted into mice, the cells correctly took up residence in the bone marrow and began producing fully functional white blood cells. The corrected cells persisted in the animal’s bone marrow and bloodstream for up to five months, providing proof of principle that this lifelong genetic condition and others like it could one day be cured without the risks and limitations of our current treatments.

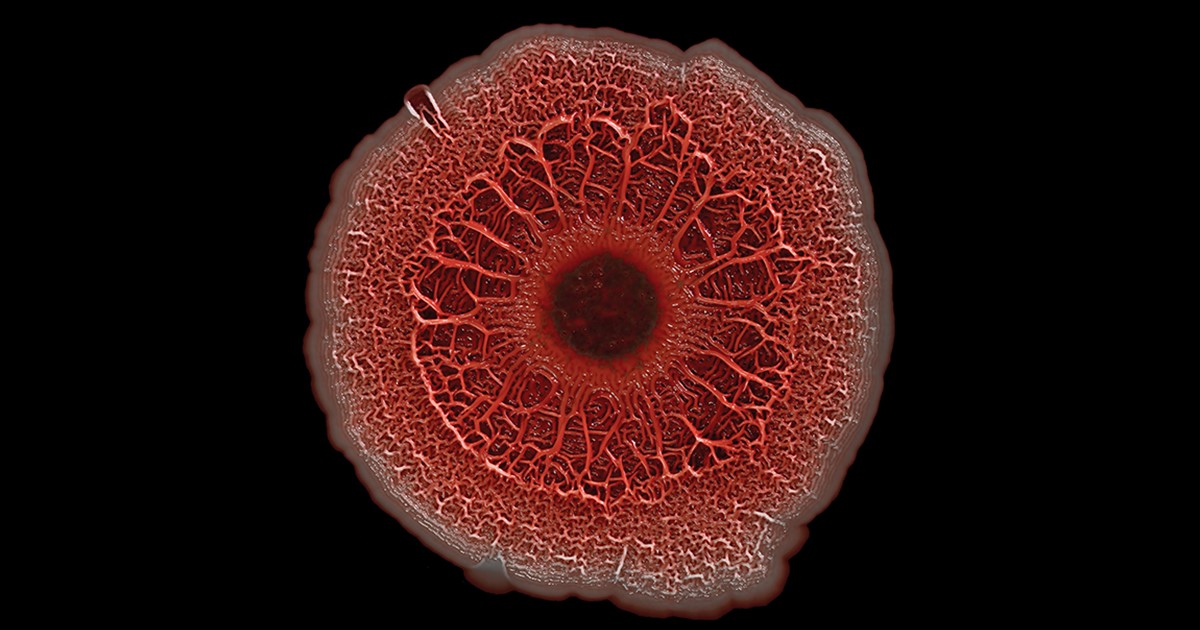

Snapshots of Life: Portrait of a Bacterial Biofilm

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

In nature, there is strength in numbers. Sometimes, those numbers also have their own unique beauty. That’s the story behind this image showing an intricate colony of millions of the single-celled bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a common culprit in the more than 700,000 hospital-acquired infections estimated to occur annually in the United States. [1]. The bacteria have self-organized into a sticky, mat-like colony called a biofilm, which allows them to cooperate with each other, adapt to changes in their environment, and ensure their survival.

In this image, the Pseudomonas biofilm has grown in a laboratory dish to about the size of a dime. Together, the millions of independent bacterial cells have created a tough extracellular matrix of secreted proteins, polysaccharide sugars, and even DNA that holds the biofilm together, stained in red. The darkened areas at the center come from the bacteria’s natural pigments.

Mouse Study Finds Microbe Might Protect against Food Poisoning

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

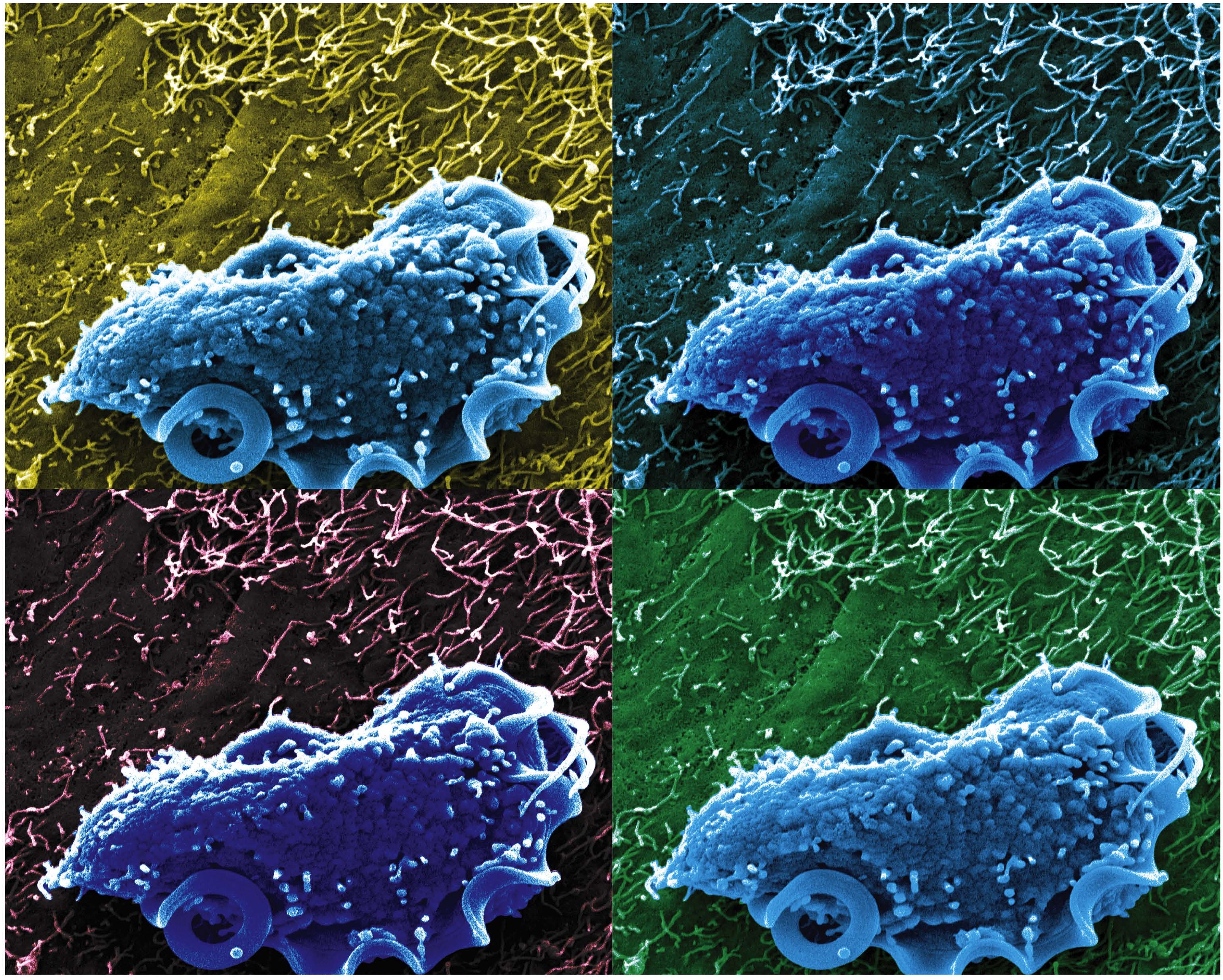

Caption: Scanning electron microscopy image of T. mu in the mouse colon.

Credit: Aleksey Chudnovskiy and Miriam Merad, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai

Recently, we humans have started to pay a lot more attention to the legions of bacteria that live on and in our bodies because of research that’s shown us the many important roles they play in everything from how we efficiently metabolize food to how well we fend off disease. And, as it turns out, bacteria may not be the only interior bugs with the power to influence our biology positively—a new study suggests that an entirely different kingdom of primarily single-celled microbes, called protists, may be in on the act.

In a study published in the journal Cell, an NIH-funded research team reports that it has identified a new protozoan, called Tritrichomonas musculis (T. mu), living inside the gut of laboratory mice. That sounds bad—but actually this little wriggler was potentially providing a positive benefit to the mice. Not only did T. mu appear to boost the animals’ immune systems, it spared them from the severe intestinal infection that typically occurs after eating food contaminated with toxic Salmonella bacteria. While it’s not yet clear if protists exist that can produce similar beneficial effects in humans, there is evidence that a close relative of T. mu frequently resides in the intestines of people around the world.

Previous Page Next Page

Many people still regard bacteria and other microbes just as disease-causing germs. But it’s a lot more complicated than that. In fact, it’s become increasingly clear that the healthy human body is teeming with microorganisms, many of which play essential roles in our metabolism, our immune response, and even our mental health. We are not just an organism, we are a “superorganism” made up of human cells and microbial cells—and the microbes outnumber us! Fueling this new understanding is NIH’s Human Microbiome Project (HMP), a quest begun a decade ago to explore the microbial makeup of healthy Americans.

Many people still regard bacteria and other microbes just as disease-causing germs. But it’s a lot more complicated than that. In fact, it’s become increasingly clear that the healthy human body is teeming with microorganisms, many of which play essential roles in our metabolism, our immune response, and even our mental health. We are not just an organism, we are a “superorganism” made up of human cells and microbial cells—and the microbes outnumber us! Fueling this new understanding is NIH’s Human Microbiome Project (HMP), a quest begun a decade ago to explore the microbial makeup of healthy Americans.