News

COVID-19 Vaccines Protect the Family, Too

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Any of the available COVID-19 vaccines offer remarkable personal protection against the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. So, it also stands to reason that folks who are vaccinated will reduce the risk of spreading the virus to family members within their households. That protection is particularly important when not all family members can be immunized—as when there are children under age 12 or adults with immunosuppression in the home. But just how much can vaccines help to protect families from COVID-19 when only some, not all, in the household have immunity?

A Swedish study, published recently in the journal JAMA Internal Medicine, offers some of the first hard figures on this topic, and the findings are quite encouraging [1]. The data show that people without any immunity against COVID-19 were at considerably lower risk of infection and hospitalization when other members of their family had immunity, either from a natural infection or vaccination. In fact, the protective effect on family members went up as the number of immune family members increased.

The findings come from a team led by Peter Nordström, Umeå University, Sweden. Like in the United States, vaccinations in Sweden initially were prioritized for high-risk groups and people with certain preexisting conditions. As a result, Swedish families have functioned, often in close contact, as a mix of immune and susceptible individuals over the course of the pandemic.

To explore these family dynamics in greater detail, the researchers relied on nationwide registries to identify all Swedes who had immunity to SARS-COV-2 from either a confirmed infection or vaccination by May 26, 2021. The researchers identified more than 5 million individuals who’d been either diagnosed with COVID-19 or vaccinated and then matched them to a control group without immunity. They also limited the analysis to individuals in families with two to five members of mixed immune status.

This left them with about 1.8 million people from more than 800,000 families. The situation in Sweden is also a little unique from most Western nations. Somewhat controversially, the Swedish government didn’t order a mandatory citizen quarantine to slow the spread of the virus.

The researchers found in the data a rising protective effect for those in the household without immunity as the number of immune family members increased. Families with one immune family member had a 45 to 61 percent lower risk of a COVID-19 infection in the home than those who had none. Those with two immune family members enjoyed more protection, with a 75 to 86 percent reduction in risk of COVID-19. For those with three or four immune family members, the protection went up to more than 90 percent, topping out at 97 percent protection. The results were similar when the researchers limited the analysis to COVID-19 illnesses serious enough to warrant a hospital stay.

The findings confirm that vaccination is incredibly important not only for individual protection, but also for reducing transmission, especially within families and those with whom we’re in close physical contact. It’s also important to note that the findings apply to the original SARS-CoV-2 variant, which was dominant when the study was conducted. But we know that the vaccines offer good protection against Delta and other variants of concern.

These results show quite clearly that vaccines offer protection for individuals who lack immunity, with important implications for finally ending this pandemic. This doesn’t change the fact that all those who can and still need to get fully vaccinated should do so as soon as possible. If you are eligible for a booster shot, that’s something to consider, too. But, if for whatever reason you haven’t gotten vaccinated just yet, perhaps these new findings will encourage you to do it now for the sake of those other people you care about. This is a chance to love your family—and love your neighbor.

Reference:

[1] Association between risk of COVID-19 infection in nonimmune individuals and COVID-19 immunity in their family members. Nordström P, Ballin M, Nordström A. JAMA Intern Med. 2021 Oct 11.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Peter Nordström (Umeå University, Sweden)

First Comprehensive Census of Cell Types in Brain Area Controlling Movement

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

The primary motor cortex is the part of the brain that enables most of our skilled movements, whether it’s walking, texting on our phones, strumming a guitar, or even spiking a volleyball. The region remains a major research focus, and that’s why NIH’s Brain Research Through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies® (BRAIN) Initiative – Cell Census Network (BICCN) has just unveiled two groundbreaking resources: a complete census of cell types present in the mammalian primary motor cortex, along with the first detailed atlas of the region, located along the back of the frontal lobe in humans (purple stripe above).

This remarkably comprehensive work, detailed in a flagship paper and more than a dozen associated articles published in the journal Nature, promises to vastly expand our understanding of the primary motor cortex and how it works to keep us moving [1]. The papers also represent the collaborative efforts of more than 250 BICCN scientists from around the world, teaming up over many years.

Started in 2013, the BRAIN Initiative is an ambitious project with a range of groundbreaking goals, including the creation of an open-access reference atlas that catalogues all of the brain’s many billions of cells. The primary motor cortex was one of the best places to get started on assembling an atlas because it is known to be well conserved across mammalian species, from mouse to human. There’s also a rich body of work to aid understanding of more precise cell-type information.

Taking advantage of recent technological advances in single-cell analysis, the researchers categorized into different types the millions of neurons and other cells in this brain region. They did so on the basis of morphology, or shape, of the cells, as well as their locations and connections to other cells. The researchers went even further to characterize and sort cells based on: their complex patterns of gene expression, the presence or absence of chemical (or epigenetic) marks on their DNA, the way their chromosomes are packaged into chromatin, and their electrical properties.

The new data and analyses offer compelling evidence that neural cells do indeed fall into distinct types, with a high degree of correspondence across their molecular genetic, anatomical, and physiological features. These findings support the notion that neural cells can be classified into molecularly defined types that are also highly conserved or shared across mammalian species.

So, how many cell types are there? While that’s an obvious question, it doesn’t have an easy answer. The number varies depending upon the method used for sorting them. The researchers report that they have identified about 25 classes of cells, including 16 different neuronal classes and nine non-neuronal classes, each composed of multiple subtypes of cells.

These 25 classes were determined by their genetic profiles, their locations, and other characteristics. They also showed up consistently across species and using different experimental approaches, suggesting that they have important roles in the neural circuitry and function of the motor cortex in mammals.

Still, many precise features of the cells don’t fall neatly into these categories. In fact, by focusing on gene expression within single cells of the motor cortex, the researchers identified more potentially important cell subtypes, which fall into roughly 100 different clusters, or distinct groups. As scientists continue to examine this brain region and others using the latest new methods and approaches, it’s likely that the precise number of recognized cell types will continue to grow and evolve a bit.

This resource will now serve as a springboard for future research into the structure and function of the brain, both within and across species. The datasets already have been organized and made publicly available for scientists around the world.

The atlas also now provides a foundation for more in-depth study of cell types in other parts of the mammalian brain. The BICCN is already engaged in an effort to generate a brain-wide cell atlas in the mouse, and is working to expand coverage in the atlas for other parts of the human brain.

The cell census and atlas of the primary motor cortex are important scientific advances with major implications for medicine. Strokes commonly affect this region of the brain, leading to partial or complete paralysis of the opposite side of the body.

By considering how well cell census information aligns across species, scientists also can make more informed choices about the best models to use for deepening our understanding of brain disorders. Ultimately, these efforts and others underway will help to enable precise targeting of specific cell types and to treat a wide range of brain disorders that affect thinking, memory, mood, and movement.

Reference:

[1] A multimodal cell census and atlas of the mammalian primary motor cortex. BRAIN Initiative Cell Census Network (BICCN). Nature. Oct 6, 2021.

Links:

NIH Brain Research Through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies® (BRAIN) Initiative (NIH)

BRAIN Initiative – Cell Census Network (BICCN) (NIH)

NIH Support: National Institute of Mental Health; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

NIH’s Nobel Winners Demonstrate Value of Basic Research

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Last week was a big one for both NIH and me. Not only did I announce my plans to step down as NIH Director by year’s end to return to my lab full-time, I was reminded by the announcement of the 2021 Nobel Prizes of what an honor it is to be affiliated an institution with such a strong, sustained commitment to supporting basic science.

This year, NIH’s Nobel excitement started in the early morning hours of October 4, when two NIH-supported neuroscientists in California received word from Sweden that they had won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. One “wake up” call went to David Julius, University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), who was recognized for his groundbreaking discovery of the first protein receptor that controls thermosensation, the body’s perception of temperature. The other went to his long-time collaborator, Ardem Patapoutian, Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA, for his seminal work that identified the first protein receptor that controls our sense of touch.

But the good news didn’t stop there. On October 6, the 2021 Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded to NIH-funded chemist David W.C. MacMillan of Princeton University, N.J., who shared the honor with Benjamin List of Germany’s Max Planck Institute. (List also received NIH support early in his career.)

The two researchers were recognized for developing an ingenious tool that enables the cost-efficient construction of “greener” molecules with broad applications across science and industry—including for drug design and development.

Then, to turn this into a true 2021 Nobel Prize “hat trick” for NIH, we learned on October 12 that two of this year’s three Nobel winners in Economic Sciences had been funded by NIH. David Card, an NIH-supported researcher at University of California, Berkley, was recognized “for his empirical contributions to labor economics.” He shared the 2021 prize with NIH grantee Joshua Angrist of Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, and his colleague Guido Imbens of Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA, “for their methodological contributions to the analysis of causal relationships.” What a year!

The achievements of these and NIH’s 163 past Nobel Prize winners stand as a testament to the importance of our agency’s long and robust history of investing in basic biomedical research. In this area of research, scientists ask fundamental questions about how life works. The answers they uncover help us to understand the principles, mechanisms, and processes that underlie living organisms, including the human body in sickness and health.

What’s more, each advance builds upon past discoveries, often in unexpected ways and sometimes taking years or even decades before they can be translated into practical results. Recent examples of life-saving breakthroughs that have been built upon years of fundamental biomedical research include the mRNA vaccines for COVID-19 and the immunotherapy approaches now helping people with many types of cancer.

Take the case of the latest Nobels. Fundamental questions about how the human body responds to medicinal plants were the initial inspiration behind the work of UCSF’s Julius. He’d noticed that studies from Hungary found that a natural chemical in chili peppers, called capsaicin, activated a subgroup of neurons to create the painful, burning sensation that most of us have encountered from having a bit too much hot sauce. But what wasn’t known was the molecular mechanism by which capsaicin triggered that sensation.

In 1997, having settled on the best experimental approach to study this question, Julius and colleagues screened millions of DNA fragments corresponding to genes expressed in the sensory neurons that were known to interact with capsaicin. In a matter of weeks, they had pinpointed the gene encoding the protein receptor through which capsaicin interacts with those neurons [1]. Julius and team then determined in follow-up studies that the receptor, later named TRPV1, also acts as a thermal sensor on certain neurons in the peripheral nervous system. When capsaicin raises the temperature to a painful range, the receptor opens a pore-like ion channel in the neuron that then transmit a signal for the unpleasant sensation on to the brain.

In collaboration with Patapoutian, Julius then turned his attention from hot to cold. The two used the chilling sensation of the active chemical in mint, menthol, to identify a protein called TRPM8, the first receptor that senses cold [2, 3]. Additional pore-like channels related to TRPV1 and TRPM8 were identified and found to be activated by a range of different temperatures.

Taken together, these breakthrough discoveries have opened the door for researchers around the world to study in greater detail how our nervous system detects the often-painful stimuli of hot and cold. Such information may well prove valuable in the ongoing quest to develop new, non-addictive treatments for pain. The NIH is actively pursuing some of those avenues through its Helping to End Addiction Long-termSM (HEAL) Initiative.

Meanwhile, Patapoutian was busy cracking the molecular basis of another basic sense: touch. First, Patapoutian and his collaborators identified a mouse cell line that produced a measurable electric signal when individual cells were poked. They had a hunch that the electrical signal was generated by a protein receptor that was activated by physical pressure, but they still had to identify the receptor and the gene that coded for it. The team screened 71 candidate genes with no luck. Then, on their 72nd try, they identified a touch receptor-coding gene, which they named Piezo1, after the Greek word for pressure [4].

Patapoutian’s group has since found other Piezo receptors. As often happens in basic research, their findings have taken them in directions they never imagined. For example, they have discovered that Piezo receptors are involved in controlling blood pressure and sensing whether the bladder is full. Fascinatingly, these receptors also seem to play a role in controlling iron levels in red blood cells, as well as controlling the actions of certain white blood cells, called macrophages.

Turning now to the 2021 Nobel in Chemistry, the basic research of MacMillan and List has paved the way for addressing a major unmet need in science and industry: the need for less expensive and more environmentally friendly catalysts. And just what is a catalyst? To build the synthetic molecules used in drugs and a wide range of other materials, chemists rely on catalysts, which are substances that control and accelerate chemical reactions without becoming part of the final product.

It was long thought there were only two major categories of catalysts for organic synthesis: metals and enzymes. But enzymes are large, complex proteins that are hard to scale to industrial processes. And metal catalysts have the potential to be toxic to workers, as well as harmful to the environment. Then, about 20 years ago, List and MacMillan, working independently from each other, created a third type of catalyst. This approach, known as asymmetric organocatalysis [5, 6], builds upon small organic molecule catalysts that have a stable framework of carbon atoms, to which more active chemical groups can attach, often including oxygen, nitrogen, sulfur, or phosphorus.

Organocatalysts have gone on to be applied in ways that have proven to be more cost effective and environmentally friendly than using traditional metal or enzyme catalysts. In fact, this precise new tool for molecular construction is now being used to build everything from new pharmaceuticals to light-absorbing molecules used in solar cells.

That brings us to the Nobel Prize in the Economic Sciences. This year’s laureates showed that it’s possible to reach cause-and-effect answers to questions in the social sciences. The key is to evaluate situations in groups of people being treated differently, much like the design of clinical trials in medicine. Using this “natural experiment” approach in the early 1990s, David Card produced novel economic analyses, showing an increase in the minimum wage does not necessarily lead to fewer jobs. In the mid-1990s, Angrist and Imbens then refined the methodology of this approach, showing that precise conclusions can be drawn from natural experiments that establish cause and effect.

Last year, NIH added the names of three scientists to its illustrious roster of Nobel laureates. This year, five more names have been added. Many more will undoubtedly be added in the years and decades ahead. As I’ve said many times over the past 12 years, it’s an extraordinary time to be a biomedical researcher. As I prepare to step down as the Director of this amazing institution, I can assure you that NIH’s future has never been brighter.

References:

[1] The capsaicin receptor: a heat-activated ion channel in the pain pathway. Caterina MJ, Schumacher MA, Tominaga M, Rosen TA, Levine JD, Julius D. Nature 1997:389:816-824.

[2] Identification of a cold receptor reveals a general role for TRP channels in thermosensation. McKemy DD, Neuhausser WM, Julius D. Nature 2002:416:52-58.

[3] A TRP channel that senses cold stimuli and menthol. Peier AM, Moqrich A, Hergarden AC, Reeve AJ, Andersson DA, Story GM, Earley TJ, Dragoni I, McIntyre P, Bevan S, Patapoutian A. Cell 2002:108:705-715.

[4] Piezo1 and Piezo2 are essential components of distinct mechanically activated cation channels. Coste B, Mathur J, Schmidt M, Earley TJ, Ranade S, Petrus MJ, Dubin AE, Patapoutian A. Science 2010:330: 55-60.

[5] Proline-catalyzed direct asymmetric aldol reactions. List B, Lerner RA, Barbas CF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122, 2395–2396 (2000).

[6] New strategies for organic catalysis: the first highly enantioselective organocatalytic Diels-AlderReaction. Ahrendt KA, Borths JC, MacMillan DW. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 4243-4244.

Links:

Basic Research – Digital Media Kit (NIH)

Curiosity Creates Cures: The Value and Impact of Basic Research (National Institute of General Medical Sciences/NIH)

Explaining How Research Works (NIH)

NIH Basics, Collins FS, Science, 3 Aug 2012. 337; 6094: 503.

NIH’s Commitment to Basic Science, Mike Lauer, Open Mike Blog, March 25, 2016

Nobel Laureates (NIH)

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2021 (The Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden)

Video: Announcement of the 2021 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine (YouTube)

The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2021 (The Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institutet)

Video: Announcement of the 2021 Nobel Prize in Chemistry (YouTube)

The Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences (The Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institutet)

Video: Announcement of the 2021 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences (YouTube)

Julius Lab (University of California San Francisco)

The Patapoutian Lab (Scripps Research, La Jolla, CA)

Benjamin List (Max-Planck-Institut für Kohlenforschung, Mülheim an der Ruhr, Germany)

The MacMillan Group (Princeton University, NJ)

David Card (University of California, Berkeley)

Joshua Angrist (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge)

NIH Support:

David Julius: National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke; National Institute of General Medical Sciences; National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research

Ardem Patapoutian: National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke; National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

David W.C. MacMillan: National Institute of General Medical Sciences

David Card: National Institute on Aging; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development

Joshua Angrist: Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development

Learning to Protect Communities with COVID-19 Home Testing Programs

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

With most kids now back in school, parents face a new everyday concern: determining whether their child’s latest cough or sneeze might be a sign of COVID-19. If so, parents will want to keep their child at home to protect other students and staff, while also preventing the spread of the virus in their communities. And if it’s the parent who has a new cough, they also will want to know if the reason is COVID-19 before going to work or the store.

Home tests are now coming online to help concerned people make the right choice quickly. As more COVID-19 home tests enter the U.S. marketplace, research continues to help optimize their use. That’s why NIH and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) are teaming up in several parts of the country to provide residents age 2 and older with free home-testing kits for COVID-19. These reliable, nasal swab tests provide yes-or-no answers in about 15 minutes for parents and anyone else concerned about their possible exposure to the novel coronavirus.

The tests are part of an initiative called Say Yes! COVID Test (SYCT) that’s evaluating how best to implement home-testing programs within range of American communities, both urban and rural. The lessons learned are providing needed science-based data to help guide public health officials who are interested in implementing similar home-testing programs in communities throughout their states.

After successful eight-week pilot programs this past spring and summer in parts of North Carolina, Tennessee, and Michigan, SYCT is partnering this fall with four new communities. They are Fulton County, GA; Honolulu County, HI; Louisville Metro, KY; and Marion County, IN.

The Georgia and Hawaii partnerships, launched on September 20, are already off to a flying start. In Fulton County, home to Atlanta and several small cities, 21,673 direct-to-consumer orders (173,384 tests) have already been received. In Honolulu County, demand for the tests has exceeded all expectations, with 91,000 orders received in the first week (728,000 tests). The online ordering has now closed in Hawaii, and the remaining tests will be distributed on the ground through the local public health department.

SYCT offers the Quidel QuickVue® At-Home COVID-19 test, which is supplied through the NIH Rapid Acceleration of Diagnostics (RADx) initiative. The antigen test uses a self-collected nasal swab sample that is placed in a test tube containing solution, followed by a test strip. Colored lines that appear on the test strip indicate a positive or negative result—similar to a pregnancy test.

The program allows residents in participating counties to order free home tests online or for in-person pick up at designated sites in their community. Each resident can ask for eight rapid tests, which equals two weekly tests over four weeks. An easy-to-navigate website like this one and a digital app, developed by initiative partner CareEvolution, are available for residents to order their tests, sign-up for testing reminders, and allow voluntary test result reporting to the public health department.

SYCT will generate data to answer several important questions about self or home-testing. They include questions about consumer demand, ensuring full community access, testing behavior, willingness to report test results, and, above all, effectiveness in controlling the spread of SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19

Researchers at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill; Duke University, Durham, NC; and the UMass Chan Medical School, Worcester, MA, will help crunch the data and look for guiding themes. They will also conduct a study pre- and post-intervention to evaluate levels of SARS-CoV-2 in the community, including using measures of virus in wastewater. In addition, researchers will compare their results to other counties similar in size and infection rates, but that are not participating in a free testing initiative.

The NIH and CDC are exploring ways to scale a SYCT-like program nationally to communities experiencing surges in COVID-19. The Biden Administration also recently invoked the Defense Production Act to purchase millions of COVID-19 home tests to help accelerate their availability and offer them at a lower cost to more Americans. That encompasses many different types of people, including concerned parents who need a quick-and-accurate answer on whether their children’s cough or sneeze is COVID-19.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Rapid Acceleration of Diagnostics (RADx) (NIH)

NIH Support: National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities

Most Vaccine-Hesitant People Remain Willing to Change Their Minds

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

As long and difficult as this pandemic has been, I remain overwhelmingly grateful for the remarkable progress being made, including the hard work of so many people to develop rapidly and then deploy multiple life-saving vaccines. And yet, grave concerns remain that vaccine hesitancy—the reluctance of certain individuals and groups to get themselves and their children vaccinated—could cause this pandemic to go on much longer than it should.

We’re seeing the results of such hesitancy in the news every day, highlighting the rampant spread of COVID-19 that’s stretching our healthcare systems and resources dangerously thin in many places. The vast majority of those currently hospitalized with COVID-19 are unvaccinated, and most of those tragic 2,000 deaths each day could have been prevented. The stories of children and adults who realized too late the importance of getting vaccinated are heartbreaking.

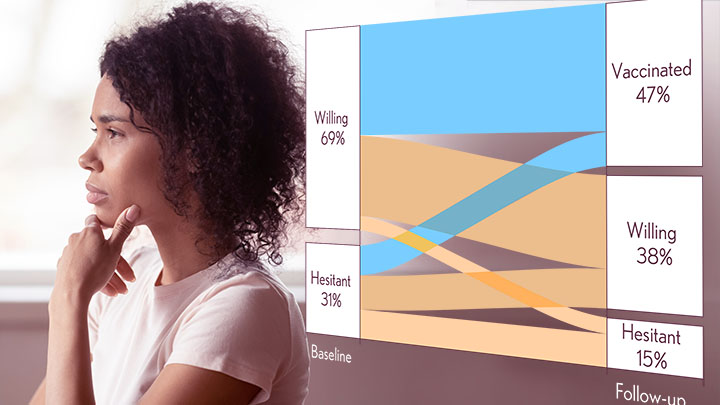

With these troubling realities in mind, I was encouraged to see a new study in the journal JAMA Network Open that tracked vaccine hesitancy over time in a random sample of more than 4,600 Americans. This national study shows that vaccine hesitancy isn’t set in stone. Over the course of this pandemic, hesitancy has decreased, and many who initially said no are now getting their shots. Many others who remain unvaccinated lean toward making an appointment.

The findings come from Aaron Siegler and colleagues, Emory University, Atlanta. They were interested in studying how entrenched vaccine hesitancy would be over time. The researchers also wanted to see how often those who were initially hesitant went on to get their shots.

To find out, they recruited a diverse, random, national sampling of individuals from August to December 2020, just before the first vaccines were granted Emergency Use Approval and became widely available. They wanted to get a baseline, or starting characterization, on vaccine hesitancy. Participants were asked two straightforward questions, “Have you received the COVID-19 vaccine?” and “How likely are you to get it in the future?” From March to April 2021, the researchers followed up by asking participants the same questions again when vaccines were more readily available to many (although still not all) adults.

The survey’s initial results showed that nearly 70 percent of respondents were willing to get vaccinated at the outset, with the other 30 percent expressing some hesitancy. The good news is among the nearly 3,500 individuals who answered the survey at follow-up, about a third who were initially vaccine hesitant already had received at least one shot. Another third also said that they’d now be willing to get the vaccine, even though they hadn’t just yet.

Among those who initially expressed a willingness to get vaccinated, about half had done so at follow up by spring 2021 (again, some still may not have been eligible). Forty percent said they were likely to get vaccinated. However, 7 percent of those who were initially willing said they were now less likely to get vaccinated than before.

There were some notable demographic differences. Folks over age 65, people who identified as non-Hispanic Asians, and those with graduate degrees were most likely to have changed their minds and rolled up their sleeves. Only about 15 percent in any one of these groups said they weren’t willing to be vaccinated. Most reluctant older people ultimately got their shots.

The picture was more static for people aged 45 to 54 and for those with a high school education or less. The majority of those remained unvaccinated, and about 40 percent still said they were unlikely to change their minds.

At the outset, people of Hispanic heritage were as willing as non-Hispanic whites to get vaccinated. At follow-up, however, fewer Hispanics than non-Hispanic whites said they’d gotten their shots. This finding suggests that, in addition to some hesitancy, there may be significant barriers still to overcome to make vaccination easier and more accessible to certain groups, including Hispanic communities from Central and South America.

Willingness among non-Hispanic Blacks was consistently lowest, but nearly half had gotten at least one dose of vaccine by the time they completed the second survey. That’s comparable to the vaccination rate in white study participants. For more recent data on vaccination rates by race/ethnicity, see this report from the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Overall, while a small number of respondents grew more reluctant over time, most people grew more comfortable with the vaccines and were more likely to say they’d get vaccinated, if they hadn’t already. In fact, by the end of the study, the hesitant group had shrunk from 31 to 15 percent. It’s worth noting that the researchers checked the validity of self-reported vaccination using antibody tests and the results matched up rather well.

This is all mostly good news, but there’s clearly more work to do. An estimated 70 million eligible Americans have yet to get their first shot, and remain highly vulnerable to infection and serious illness from the Delta variant. They are capable of spreading the virus to other vulnerable people around them (including children), and incubating the next variants that might provide more resistance to the vaccines and therapies. They are also at risk for Long COVID, even after a relatively mild acute illness.

The work ahead involves answering questions and addressing concerns from people who remain hesitant. It’s also incredibly important to reach out to those willing, but unvaccinated, individuals, to see what can be done to help them get their shots. If you happen to be one of those, it’s easy to find the places near you that have free vaccines ready to administer. Go to vaccines.gov, or punch 438829 on your cell phone and enter your zip code—in less than a minute you will get the location of vaccine sites nearby.

Nearly 400 million COVID-19 vaccine doses have been administered in communities all across the United States. More than 600,000 more are being administered on average each day. And yet, more than 80,000 new infections are still reported daily, and COVID-19 still steals the lives of about 2,000 mostly unvaccinated people each day.

These vaccines are key for protecting yourself and ultimately beating this pandemic. As these findings show, the vast majority of Americans understand this and either have been vaccinated or are willing to do so. Let’s keep up the good work, and see to it that even more minds will be changed—and more individuals protected before they may find it’s too late.

Reference:

[1] Trajectory of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy over time and association of initial vaccine hesitancy with subsequent vaccination. Siegler AJ, Luisi N, Hall EW, Bradley H, Sanchez T, Lopman BA, Sullivan PS. JAMA Netw Open. 2021 Sep 1;4(9):e2126882.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

COVID-19 Vaccinations in the United States (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta)

Aaron Siegler (Emory University, Atlanta)

NIH Support: National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases

Artificial Intelligence Accurately Predicts RNA Structures, Too

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Researchers recently showed that a computer could “learn” from many examples of protein folding to predict the 3D structure of proteins with great speed and precision. Now a recent study in the journal Science shows that a computer also can predict the 3D shapes of RNA molecules [1]. This includes the mRNA that codes for proteins and the non-coding RNA that performs a range of cellular functions.

This work marks an important basic science advance. RNA therapeutics—from COVID-19 vaccines to cancer drugs—have already benefited millions of people and will help many more in the future. Now, the ability to predict RNA shapes quickly and accurately on a computer will help to accelerate understanding these critical molecules and expand their healthcare uses.

Like proteins, the shapes of single-stranded RNA molecules are important for their ability to function properly inside cells. Yet far less is known about these RNA structures and the rules that determine their precise shapes. The RNA elements (bases) can form internal hydrogen-bonded pairs, but the number of possible combinations of pairings is almost astronomical for any RNA molecule with more than a few dozen bases.

In hopes of moving the field forward, a team led by Stephan Eismann and Raphael Townshend in the lab of Ron Dror, Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA, looked to a machine learning approach known as deep learning. It is inspired by how our own brain’s neural networks process information, learning to focus on some details but not others.

In deep learning, computers look for patterns in data. As they begin to “see” complex relationships, some connections in the network are strengthened while others are weakened.

One of the things that makes deep learning so powerful is it doesn’t rely on any preconceived notions. It also can pick up on important features and patterns that humans can’t possibly detect. But, as successful as this approach has been in solving many different kinds of problems, it has primarily been applied to areas of biology, such as protein folding, in which lots of data were available for researchers to train the computers.

That’s not the case with RNA molecules. To work around this problem, Dror’s team designed a neural network they call ARES. (No, it’s not the Greek god of war. It’s short for Atomic Rotationally Equivariant Scorer.)

To start, the researchers trained ARES on just 18 small RNA molecules for which structures had been experimentally determined. They gave ARES these structural models specified only by their atomic structure and chemical elements.

The next test was to see if ARES could determine from this small training set the best structural model for RNA sequences it had never seen before. The researchers put it to the test with RNA molecules whose structures had been determined more recently.

ARES, however, doesn’t come up with the structures itself. Instead, the researchers give ARES a sequence and at least 1,500 possible 3D structures it might take, all generated using another computer program. Based on patterns in the training set, ARES scores each of the possible structures to find the one it predicts is closest to the actual structure. Remarkably, it does this without being provided any prior information about features important for determining RNA shapes, such as nucleotides, steric constraints, and hydrogen bonds.

It turns out that ARES consistently outperforms humans and all other previous methods to produce the best results. In fact, it outperformed at least nine other methods to come out on top in a community-wide RNA-puzzles contest. It also can make predictions about RNA molecules that are significantly larger and more complex than those upon which it was trained.

The success of ARES and this deep learning approach will help to elucidate RNA molecules with potentially important implications for health and disease. It’s another compelling example of how deep learning promises to solve many other problems in structural biology, chemistry, and the material sciences when—at the outset—very little is known.

Reference:

[1] Geometric deep learning of RNA structure. Townshend RJL, Eismann S, Watkins AM, Rangan R, Karelina M, Das R, Dror RO. Science. 2021 Aug 27;373(6558):1047-1051.

Links:

Structural Biology (National Institute of General Medical Sciences/NIH)

The Structures of Life (National Institute of General Medical Sciences/NIH)

RNA Biology (NIH)

Dror Lab (Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA)

NIH Support: National Cancer Institute; National Institute of General Medical Sciences

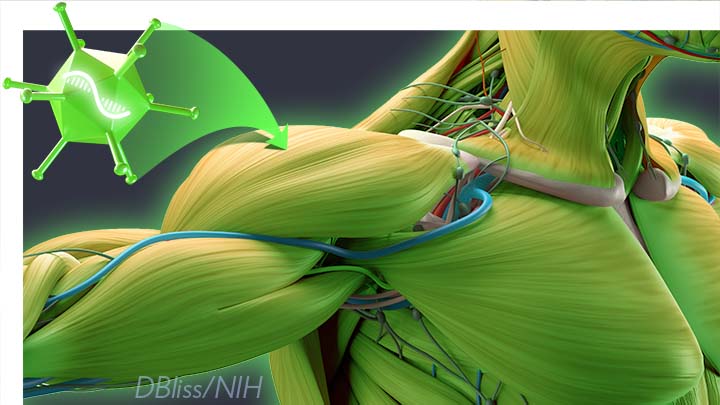

Engineering a Better Way to Deliver Therapeutic Genes to Muscles

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Amid all the progress toward ending the COVID-19 pandemic, it’s worth remembering that researchers here and around the world continue to make important advances in tackling many other serious health conditions. As an inspiring NIH-supported example, I’d like to share an advance on the use of gene therapy for treating genetic diseases that progressively degenerate muscle, such as Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD).

As published recently in the journal Cell, researchers have developed a promising approach to deliver therapeutic genes and gene editing tools to muscle more efficiently, thus requiring lower doses [1]. In animal studies, the new approach has targeted muscle far more effectively than existing strategies. It offers an exciting way forward to reduce unwanted side effects from off-target delivery, which has hampered the development of gene therapy for many conditions.

In boys born with DMD (it’s an X-linked disease and therefore affects males), skeletal and heart muscles progressively weaken due to mutations in a gene encoding a critical muscle protein called dystrophin. By age 10, most boys require a wheelchair. Sadly, their life expectancy remains less than 30 years.

The hope is gene therapies will one day treat or even cure DMD and allow people with the disease to live longer, high-quality lives. Unfortunately, the benign adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) traditionally used to deliver the healthy intact dystrophin gene into cells mostly end up in the liver—not in muscles. It’s also the case for gene therapy of many other muscle-wasting genetic diseases.

The heavy dose of viral vector to the liver is not without concern. Recently and tragically, there have been deaths in a high-dose AAV gene therapy trial for X-linked myotubular myopathy (XLMTM), a different disorder of skeletal muscle in which there may already be underlying liver disease, potentially increasing susceptibility to toxicity.

To correct this concerning routing error, researchers led by Mohammadsharif Tabebordbar in the lab of Pardis Sabeti, Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard and Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, have now assembled an optimized collection of AAVs. They have been refined to be about 10 times better at reaching muscle fibers than those now used in laboratory studies and clinical trials. In fact, researchers call them myotube AAVs, or MyoAAVs.

MyoAAVs can deliver therapeutic genes to muscle at much lower doses—up to 250 times lower than what’s needed with traditional AAVs. While this approach hasn’t yet been tried in people, animal studies show that MyoAAVs also largely avoid the liver, raising the prospect for more effective gene therapies without the risk of liver damage and other serious side effects.

In the Cell paper, the researchers demonstrate how they generated MyoAAVs, starting out with the commonly used AAV9. Their goal was to modify the outer protein shell, or capsid, to create an AAV that would be much better at specifically targeting muscle. To do so, they turned to their capsid engineering platform known as, appropriately enough, DELIVER. It’s short for Directed Evolution of AAV capsids Leveraging In Vivo Expression of transgene RNA.

Here’s how DELIVER works. The researchers generate millions of different AAV capsids by adding random strings of amino acids to the portion of the AAV9 capsid that binds to cells. They inject those modified AAVs into mice and then sequence the RNA from cells in muscle tissue throughout the body. The researchers want to identify AAVs that not only enter muscle cells but that also successfully deliver therapeutic genes into the nucleus to compensate for the damaged version of the gene.

This search delivered not just one AAV—it produced several related ones, all bearing a unique surface structure that enabled them specifically to target muscle cells. Then, in collaboration with Amy Wagers, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, the team tested their MyoAAV toolset in animal studies.

The first cargo, however, wasn’t a gene. It was the gene-editing system CRISPR-Cas9. The team found the MyoAAVs correctly delivered the gene-editing system to muscle cells and also repaired dysfunctional copies of the dystrophin gene better than the CRISPR cargo carried by conventional AAVs. Importantly, the muscles of MyoAAV-treated animals also showed greater strength and function.

Next, the researchers teamed up with Alan Beggs, Boston Children’s Hospital, and found that MyoAAV was effective in treating mouse models of XLMTM. This is the very condition mentioned above, in which very high dose gene therapy with a current AAV vector has led to tragic outcomes. XLMTM mice normally die in 10 weeks. But, after receiving MyoAAV carrying a corrective gene, all six mice had a normal lifespan. By comparison, mice treated in the same way with traditional AAV lived only up to 21 weeks of age. What’s more, the researchers used MyoAAV at a dose 100 times lower than that currently used in clinical trials.

While further study is needed before this approach can be tested in people, MyoAAV was also used to successfully introduce therapeutic genes into human cells in the lab. This suggests that the early success in animals might hold up in people. The approach also has promise for developing AAVs with potential for targeting other organs, thereby possibly providing treatment for a wide range of genetic conditions.

The new findings are the result of a decade of work from Tabebordbar, the study’s first author. His tireless work is also personal. His father has a rare genetic muscle disease that has put him in a wheelchair. With this latest advance, the hope is that the next generation of promising gene therapies might soon make its way to the clinic to help Tabebordbar’s father and so many other people.

Reference:

[1] Directed evolution of a family of AAV capsid variants enabling potent muscle-directed gene delivery across species. Tabebordbar M, Lagerborg KA, Stanton A, King EM, Ye S, Tellez L, Krunnfusz A, Tavakoli S, Widrick JJ, Messemer KA, Troiano EC, Moghadaszadeh B, Peacker BL, Leacock KA, Horwitz N, Beggs AH, Wagers AJ, Sabeti PC. Cell. 2021 Sep 4:S0092-8674(21)01002-3.

Links:

Muscular Dystrophy Information Page (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke/NIH)

X-linked myotubular myopathy (Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center/National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences/NIH)

Somatic Cell Genome Editing (Common Fund/NIH)

Mohammadsharif Tabebordbar (Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard and Harvard University, Cambridge, MA)

Sabeti Lab (Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard and Harvard University)

NIH Support: Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; Common Fund

Breakthrough Infections in Vaccinated People Less Likely to Cause ‘Long COVID’

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

There’s no question that vaccines are making a tremendous difference in protecting individuals and whole communities against infection and severe illness from SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19. And now, there’s yet another reason to get the vaccine: in the event of a breakthrough infection, people who are fully vaccinated also are substantially less likely to develop Long COVID Syndrome, which causes brain fog, muscle pain, fatigue, and a constellation of other debilitating symptoms that can last for months after recovery from an initial infection.

These important findings published in The Lancet Infectious Diseases are the latest from the COVID Symptom Study [1]. This study allows everyday citizens in the United Kingdom to download a smartphone app and self-report data on their infection, symptoms, and vaccination status over a long period of time.

Previously, the study found that 1 in 20 people in the U.K. who got COVID-19 battled Long COVID symptoms for eight weeks or more. But this work was done before vaccines were widely available. What about the risk among those who got COVID-19 for the first time as a breakthrough infection after receiving a double dose of any of the three COVID-19 vaccines (Pfizer, Moderna, AstraZeneca) authorized for use in the U.K.?

To answer that question, Claire Steves, King’s College, London, and colleagues looked to frequent users of the COVID Symptom Study app on their smartphones. In its new work, Steves’ team was interested in analyzing data submitted by folks who’d logged their symptoms, test results, and vaccination status between December 9, 2020, and July 4, 2021. The team found there were more than 1.2 million adults who’d received a first dose of vaccine and nearly 1 million who were fully vaccinated during this period.

The data show that only 0.2 percent of those who were fully vaccinated later tested positive for COVID-19. While accounting for differences in age, sex, and other risk factors, the researchers found that fully vaccinated individuals who developed breakthrough infections were about half (49 percent) as likely as unvaccinated people to report symptoms of Long COVID Syndrome lasting at least four weeks after infection.

The most common symptoms were similar in vaccinated and unvaccinated adults with COVID-19, and included loss of smell, cough, fever, headaches, and fatigue. However, all of these symptoms were milder and less frequently reported among the vaccinated as compared to the unvaccinated.

Vaccinated people who became infected were also more likely than the unvaccinated to be asymptomatic. And, if they did develop symptoms, they were half as likely to report multiple symptoms in the first week of illness. Another vaccination benefit was that people with a breakthrough infection were about a third as likely to report any severe symptoms. They also were more than 70 percent less likely to require hospitalization.

We still have a lot to learn about Long COVID, and, to get the answers, NIH has launched the RECOVER Initiative. The initiative will study tens of thousands of COVID-19 survivors to understand why many individuals don’t recover as quickly as expected, and what might be the cause, prevention, and treatment for Long COVID.

In the meantime, these latest findings offer the encouraging news that help is already here in the form of vaccines, which provide a very effective way to protect against COVID-19 and greatly reduce the odds of Long COVID if you do get sick. So, if you haven’t done so already, make a plan to protect your own health and help end this pandemic by getting yourself fully vaccinated. Vaccines are free and available near to you—just go to vaccines.gov or text your zip code to 438829.

Reference:

[1] Risk factors and disease profile of post-vaccination SARS-CoV-2 infection in UK users of the COVID Symptom Study app: a prospective, community-based, nested, case-control study. Antonelli M, Penfold RS, Merino J, Sudre CH, Molteni E, Berry S, Canas LS, Graham MS, Klaser K, Modat M, Murray B, Kerfoot E, Chen L, Deng J, Österdahl MF, Cheetham NJ, Drew DA, Nguyen LH, Pujol JC, Hu C, Selvachandran S, Polidori L, May A, Wolf J, Chan AT, Hammers A, Duncan EL, Spector TD, Ourselin S, Steves CJ. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021 Sep 1:S1473-3099(21)00460-6.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Claire Steves (King’s College London, United Kingdom)

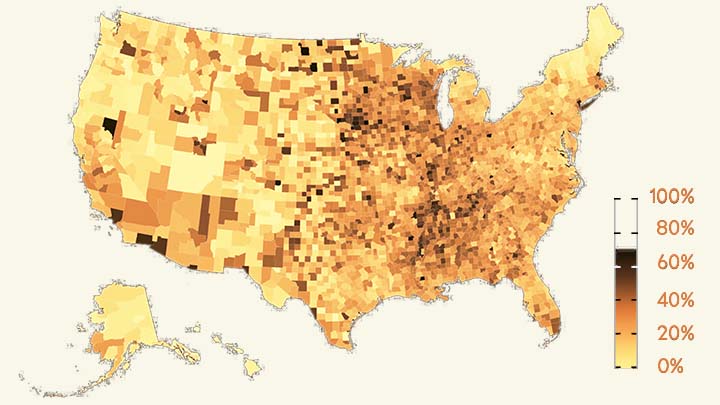

COVID-19 Infected Many More Americans in 2020 than Official Tallies Show

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

At the end of last year, you may recall hearing news reports that the number of COVID-19 cases in the United States had topped 20 million. While that number came as truly sobering news, it also likely was an underestimate. Many cases went undetected due to limited testing early in the year and a large number of infections that produced mild or no symptoms.

Now, a recent article published in Nature offers a more-comprehensive estimate that puts the true number of infections by the end of 2020 at more than 100 million [1]. That’s equal to just under a third of the U.S. population of 328 million. This revised number shows just how rapidly this novel coronavirus spread through the country last year. It also brings home just how timely the vaccines have been—and continue to be in 2021—to protect our nation’s health in this time of pandemic.

The work comes from NIH grantee Jeffrey Shaman, Sen Pei, and colleagues, Columbia University, New York. As shown above in the map, the researchers estimated the percentage of people who had been infected with SARS-CoV-2, the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19, in communities across the country through December 2020.

To generate this map, they started with existing national data on the number of coronavirus cases (both detected and undetected) in 3,142 U.S. counties and major metropolitan areas. They then factored in data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) on the number of people who tested positive for antibodies against SARS-CoV-2. These CDC data are useful for picking up on past infections, including those that went undetected.

From these data, the researchers calculated that only about 11 percent of all COVID-19 cases were confirmed by a positive test result in March 2020. By the end of the year, with testing improvements and heightened public awareness of COVID-19, the ascertainment rate (the number of infections that were known versus unknown) rose to about 25 percent on average. This measure also varied a lot across the country. For instance, the ascertainment rates in Miami and Phoenix were higher than the national average, while rates in New York City, Los Angeles, and Chicago were lower than average.

How many people were potentially walking around with a contagious SARS-CoV-2 infection? The model helps to answer this, too. On December 31, 2020, the researchers estimate that 0.77 percent of the U.S. population had a contagious infection. That’s about 1 in every 130 people on average. In some places, it was much higher. In Los Angeles, for example, nearly 1 in 40 (or 2.42 percent) had a SARS-CoV-2 infection as they rang in the New Year.

Over the course of the year, the fatality rate associated with COVID-19 dropped, at least in part due to earlier diagnosis and advances in treatment. The fatality rate went from 0.77 percent in April to 0.31 percent in December. While this is great news, it still shows that COVID-19 remains much more dangerous than seasonal influenza (which has a fatality rate of 0.08 percent).

Today, the landscape has changed considerably. Vaccines are now widely available, giving many more people immune protection without ever having to get infected. And yet, the rise of the Delta and other variants means that breakthrough infections and reinfections—which the researchers didn’t account for in their model—have become a much bigger concern.

Looking ahead to the end of 2021, Americans must continue to do everything they can to protect their communities from the spread of this terrible virus. That means getting vaccinated if you haven’t already, staying home and getting tested if you’ve got symptoms or know of an exposure, and taking other measures to keep yourself and your loved ones safe and well. These measures we take now will influence the infection rates and susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 in our communities going forward. That will determine what the map of SARS-CoV-2 infections will look like in 2021 and beyond and, ultimately, how soon we can finally put this pandemic behind us.

Reference:

[1] Burden and characteristics of COVID-19 in the United States during 2020. Pei S, Yamana TK, Kandula S, Galanti M, Shaman J. Nature. 2021 Aug 26.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Sen Pei (Columbia University, New York)

Jeffrey Shaman (Columbia University, New York)

Previous Page Next Page