Most Vaccine-Hesitant People Remain Willing to Change Their Minds

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

As long and difficult as this pandemic has been, I remain overwhelmingly grateful for the remarkable progress being made, including the hard work of so many people to develop rapidly and then deploy multiple life-saving vaccines. And yet, grave concerns remain that vaccine hesitancy—the reluctance of certain individuals and groups to get themselves and their children vaccinated—could cause this pandemic to go on much longer than it should.

We’re seeing the results of such hesitancy in the news every day, highlighting the rampant spread of COVID-19 that’s stretching our healthcare systems and resources dangerously thin in many places. The vast majority of those currently hospitalized with COVID-19 are unvaccinated, and most of those tragic 2,000 deaths each day could have been prevented. The stories of children and adults who realized too late the importance of getting vaccinated are heartbreaking.

With these troubling realities in mind, I was encouraged to see a new study in the journal JAMA Network Open that tracked vaccine hesitancy over time in a random sample of more than 4,600 Americans. This national study shows that vaccine hesitancy isn’t set in stone. Over the course of this pandemic, hesitancy has decreased, and many who initially said no are now getting their shots. Many others who remain unvaccinated lean toward making an appointment.

The findings come from Aaron Siegler and colleagues, Emory University, Atlanta. They were interested in studying how entrenched vaccine hesitancy would be over time. The researchers also wanted to see how often those who were initially hesitant went on to get their shots.

To find out, they recruited a diverse, random, national sampling of individuals from August to December 2020, just before the first vaccines were granted Emergency Use Approval and became widely available. They wanted to get a baseline, or starting characterization, on vaccine hesitancy. Participants were asked two straightforward questions, “Have you received the COVID-19 vaccine?” and “How likely are you to get it in the future?” From March to April 2021, the researchers followed up by asking participants the same questions again when vaccines were more readily available to many (although still not all) adults.

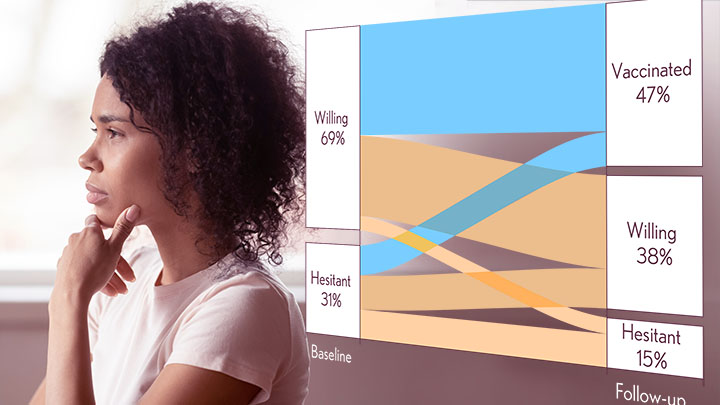

The survey’s initial results showed that nearly 70 percent of respondents were willing to get vaccinated at the outset, with the other 30 percent expressing some hesitancy. The good news is among the nearly 3,500 individuals who answered the survey at follow-up, about a third who were initially vaccine hesitant already had received at least one shot. Another third also said that they’d now be willing to get the vaccine, even though they hadn’t just yet.

Among those who initially expressed a willingness to get vaccinated, about half had done so at follow up by spring 2021 (again, some still may not have been eligible). Forty percent said they were likely to get vaccinated. However, 7 percent of those who were initially willing said they were now less likely to get vaccinated than before.

There were some notable demographic differences. Folks over age 65, people who identified as non-Hispanic Asians, and those with graduate degrees were most likely to have changed their minds and rolled up their sleeves. Only about 15 percent in any one of these groups said they weren’t willing to be vaccinated. Most reluctant older people ultimately got their shots.

The picture was more static for people aged 45 to 54 and for those with a high school education or less. The majority of those remained unvaccinated, and about 40 percent still said they were unlikely to change their minds.

At the outset, people of Hispanic heritage were as willing as non-Hispanic whites to get vaccinated. At follow-up, however, fewer Hispanics than non-Hispanic whites said they’d gotten their shots. This finding suggests that, in addition to some hesitancy, there may be significant barriers still to overcome to make vaccination easier and more accessible to certain groups, including Hispanic communities from Central and South America.

Willingness among non-Hispanic Blacks was consistently lowest, but nearly half had gotten at least one dose of vaccine by the time they completed the second survey. That’s comparable to the vaccination rate in white study participants. For more recent data on vaccination rates by race/ethnicity, see this report from the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Overall, while a small number of respondents grew more reluctant over time, most people grew more comfortable with the vaccines and were more likely to say they’d get vaccinated, if they hadn’t already. In fact, by the end of the study, the hesitant group had shrunk from 31 to 15 percent. It’s worth noting that the researchers checked the validity of self-reported vaccination using antibody tests and the results matched up rather well.

This is all mostly good news, but there’s clearly more work to do. An estimated 70 million eligible Americans have yet to get their first shot, and remain highly vulnerable to infection and serious illness from the Delta variant. They are capable of spreading the virus to other vulnerable people around them (including children), and incubating the next variants that might provide more resistance to the vaccines and therapies. They are also at risk for Long COVID, even after a relatively mild acute illness.

The work ahead involves answering questions and addressing concerns from people who remain hesitant. It’s also incredibly important to reach out to those willing, but unvaccinated, individuals, to see what can be done to help them get their shots. If you happen to be one of those, it’s easy to find the places near you that have free vaccines ready to administer. Go to vaccines.gov, or punch 438829 on your cell phone and enter your zip code—in less than a minute you will get the location of vaccine sites nearby.

Nearly 400 million COVID-19 vaccine doses have been administered in communities all across the United States. More than 600,000 more are being administered on average each day. And yet, more than 80,000 new infections are still reported daily, and COVID-19 still steals the lives of about 2,000 mostly unvaccinated people each day.

These vaccines are key for protecting yourself and ultimately beating this pandemic. As these findings show, the vast majority of Americans understand this and either have been vaccinated or are willing to do so. Let’s keep up the good work, and see to it that even more minds will be changed—and more individuals protected before they may find it’s too late.

Reference:

[1] Trajectory of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy over time and association of initial vaccine hesitancy with subsequent vaccination. Siegler AJ, Luisi N, Hall EW, Bradley H, Sanchez T, Lopman BA, Sullivan PS. JAMA Netw Open. 2021 Sep 1;4(9):e2126882.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

COVID-19 Vaccinations in the United States (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta)

Aaron Siegler (Emory University, Atlanta)

NIH Support: National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases

Dr Collins: I just read that you are leaving as the NIH Director and am very sorry to hear that. Thank you for your work and your blog, which I have enjoyed and learned much from.

Agreed, Susan. Dr. Collins was most gracious when I met him at NIH several years ago regarding participatory medicine. His professionalism, grace and wisdom will be missed.

I live in California, Our Governor announced a vaccine mandate for school kids. I have some questions.

Looking at the historical danger to children from Covid, it appears it was very low for the first type we had here. I see claims it was less dangerous than influenza for them. From the standpoint of protection for them, not the adults around them, it appears they would have been better off attending schools last year and getting infected than being where they are now, some with natural immunity from past infection, many without.

I base this on findings of studies which claim natural immunity is much better than vaccination immunity, for those who got infected with the first type and now are being exposed to Delta variant. And, though this is not yet proven I guess , reports I see that a universal vaccine for all future types of this virus, which will work by generating immune response to several part of the virus, not just “the Spike” or RBD, is being developed.

It seems to me a kid who got infected back then is very immune now, to multiple variants (if that study is correct) whereas, IF he’d been given a vaccine, he would be much less protected from Delta and whatever comes next.

So, if Delta is bad enough for kids, if the severe illness and fatality rate is just too high, then kids need whatever vaccines we have now, (even if not perfect) but if it is not, the same principle applies- let them get sick so they get antibodies to every part of the virus (the theory behind the universal vaccine is, unlike the Spike, other parts of the virus are not mutating and maybe can not without inactivating the virus, so the universal vaccine will target them by exposing the immune system to them. The universal vaccine will generate several types of antibodies to many different sites on the virus)

So, this is my question, does this same principle still apply to Delta or not? It is not really clear to me because it depends on the Delta case fatality rate for kids and if it is worse.

If Delta is not bad enough, maybe it is better to wait for the universal vaccine than give the kids what we have now? Not that the vaccine is dangerous, but if the virus mutates to evade our current vaccines, we will need to do this all over again – but if kids get infected, OR a universal vaccine, and that gives them permanent immunity, we will not need to do anything with them in the future.

Dr. Collins, I have just learned you are retiring after many years of faithful service. I wish you well in your retirement.

Thank you for your hard work, Dr. Collins, including this blog that has been so informative! I really appreciate your willingness to “do science” while publicly proclaiming your faith.

I would love to see more information about those who have had COVID-19 (prior to shots being available) and the necessity of having a shot if the antibodies are high. I speak from personal experience. I had the first shot 3 months after contracting COVID 19 and had an extreme reaction (almost seizure like). I had the antibody blood work done in April in lieu of having shot #2 and they were very strong. I also am experiencing some mild “long” Covid symptoms (loss of smell and taste, fatigue) My allergist does not recommend a second shot. I’d love more information regarding these situations. I am sure I am not the only one.

Eileen F – There was a study claiming much better protection from natural immunity, having been sick, than you can get with any vaccine – I think this is a huge issue potentially, but the authorities in some areas are pushing “one size fits all” with the apparent assumption that adverse reactions to the vaccine by people who were previously infected are not bad enough to be worth worrying about. My daughter, who is young enough that it is likely she would have an asymptomatic infection, and was around a sick person – had a strong reaction to her shot – JJ type. I assume this was due to previous infection, and really it might be worth testing her to see- because I might want to know before deciding on my own booster shot – I had a very slight response to the first shot but laid in bed for two days starting about 10 hours after the second shot, ending about 3 days later – nasty. I know I was not infected previously, but taking two large “doses” (I put it in quotes because it’s indirect with mRNA) of antigen only 3 weeks apart was enough to knock me out – but many institutions are not going to even let you prove you have high antibody titers – vaccination proof or nothing. I wish CDC would come out and say natural antibodies are sufficient, as their recently funded study seems to indicate.

Eileen F, I am in a similar situation, with surely long Covid and a daily unexplained fever of 100-102. I feel terrible, with flu like symptoms since for over a year now. Please share with me anything you may learn from here or elsewhere. I’m at a loss of what do or how to proceed. I hope you are feeling better and are getting good care.

Thank you for all of your work as Director of NIH, and thank you so much for this blog and the information and explanations that you have taken the time to share. Your coverage of COVID news and research on here has been a much needed and welcomed source of scientific sanity. (Also, thank you for writing about more than just COVID.) I wish you all the best with your future work in the NHGRI lab.

I received my third shot, the booster shot, for the Pfizer vaccine today after waiting a little more than six months since my last shot and also got the flu shot to chase it all down. I got the flu during the 1957 outbreak when I was five and was hospitalized, my parents told me I was unlikely to survive. The flu is no joke and it’s not just a bad cold. You feel like you have been hit by a truck. Today I have a beautiful 8 year old daughter who can not yet get a COVID vaccine. Her safety rests with the population getting the COVID vaccination. Please think of all the innocent people you could infect and possibly kill by not getting vaccinated. Do the right and smart thing, get your COVID shot now. Show love by protecting yourself and those around you.

As the baton gets passed from Harold Varmus of oncogene Nobel to Francis Collins of the Human Genome project, who is most pertinent to pressing societal issues in the biomedical field? What is more pressing? Somehow, given where we are now, it certainly rings bells on the Asilomar Conference regarding recombinant DNA. Hopefully the move quick and break things attitude doesn’t parlay into the applications of genomics in today’s society–the next generation is likely to remember.

please all get vaccinated and save the world from this pandemic.