2016 May

Gene Duplication: New Analysis Shows How Extra Copies Split the Work

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

The human genome contains more than 20,000 protein-coding genes, which carry the instructions for proteins essential to the structure and function of our cells, tissues and organs. Some of these genes are very similar to each other because, as the genomes of humans and other mammals evolve, glitches in DNA replication sometimes result in extra copies of a gene being made. Those duplicates can be passed along to subsequent generations and, on very rare occasions, usually at a much later point in time, acquire additional modifications that may enable them to serve new biological functions. By starting with a protein shape that has already been fine-tuned for one function, evolution can produce a new function more rapidly than starting from scratch.

The human genome contains more than 20,000 protein-coding genes, which carry the instructions for proteins essential to the structure and function of our cells, tissues and organs. Some of these genes are very similar to each other because, as the genomes of humans and other mammals evolve, glitches in DNA replication sometimes result in extra copies of a gene being made. Those duplicates can be passed along to subsequent generations and, on very rare occasions, usually at a much later point in time, acquire additional modifications that may enable them to serve new biological functions. By starting with a protein shape that has already been fine-tuned for one function, evolution can produce a new function more rapidly than starting from scratch.

Pretty cool! But it leads to a question that’s long perplexed evolutionary biologists: Why don’t duplicate genes vanish from the gene pool almost as soon as they appear? After all, instantly doubling the amount of protein produced in an organism is usually a recipe for disaster—just think what might happen to a human baby born with twice as much insulin or clotting factor as normal. At the very least, duplicate genes should be unnecessary and therefore vulnerable to being degraded into functionless pseudogenes as new mutations arise over time

An NIH-supported team offers a possible answer to this question in a study published in the journal Science. Based on their analysis of duplicate gene pairs in the human and mouse genomes, the researchers suggest that extra genes persist in the genome because of rapid changes in gene activity. Instead of the original gene producing 100 percent of a protein in the body, the gene duo quickly divvies up the job [1]. For instance, the original gene might produce roughly 50 percent and its duplicate the other 50 percent. Most importantly, organisms find the right balance and the duplicate genes can easily survive to be passed along to their offspring, providing fodder for continued evolution.

Creative Minds: Breaking Size Barriers in Cryo-Electron Microscopy

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Dmitry Lyumkis

When Dmitry Lyumkis headed off to graduate school at The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA, he had thoughts of becoming a synthetic chemist. But he soon found his calling in a nearby lab that imaged proteins using a technique known as single-particle cryo-electron microscopy (EM). Lyumkis was amazed that the team could take a purified protein, flash-freeze it in liquid nitrogen, and then fire electrons at the protein, capturing the resulting image with a special camera. Also amazing was the sophisticated computer software that analyzed the raw 2D camera images, merging the data and reconstructing it into 3D representations of the protein.

The work was profoundly complex, but Lyumkis thrives on solving extremely difficult puzzles. He joined the Scripps lab to become a structural biologist and a few years later used single-particle cryo-EM to help determine the atomic structure of a key protein on the surface of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), the cause of AIDS. The protein had been considered one of the greatest challenges in structural biology and a critical target in developing an AIDS vaccine [1].

Now, Lyumkis has plans to take single-particle cryo-EM to a whole new level—literally. He wants to develop new methods that allow it to model the atomic structures of much smaller proteins. Right now, single-particle cryo-EM has worked with proteins as small as roughly 150 kilodaltons, a measure of a protein’s molecular weight (the approximate average mass of a protein is 53 kDa). Lyumkis plans to drop that number well below 100 kDa, noting that if his new methods work as he hopes, there should be very little, if any, lower size limit to get the technique to work. He envisions generating within a matter of days or weeks the precise structure of an average-sized protein involved in a disease, and then potentially handing it off as an atomic model for drug developers to target for more effective treatment.

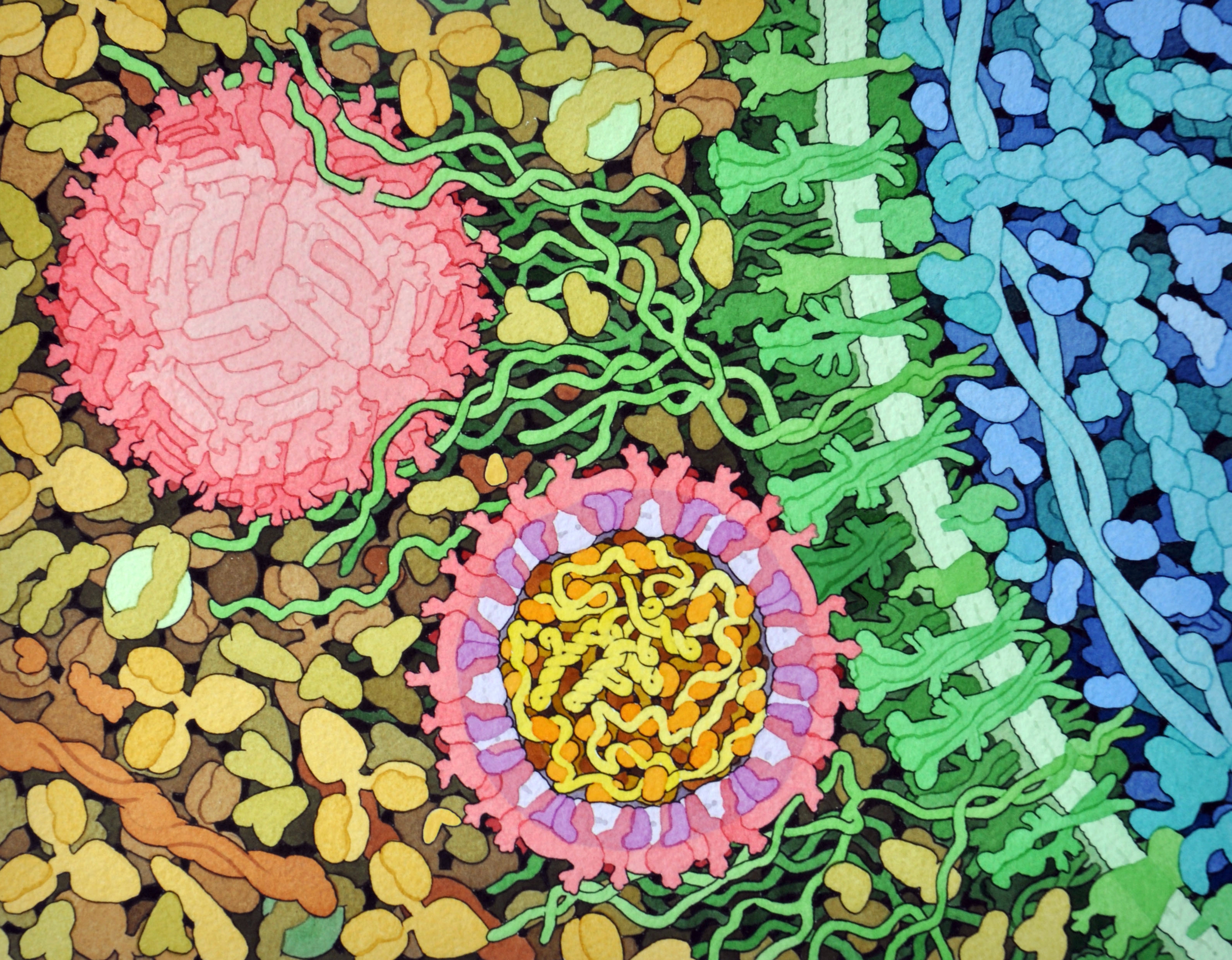

Snapshots of Life: Portrait of Zika Virus

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: David Goodsell, The Scripps Research Institute

This lively interplay of shape and color is an artistic rendering of the Zika virus preparing to enter a cell (blue) by binding to its protein receptors (green). The spherical structures (pink) represent two Zika viruses in a blood vessel filled with blood plasma cells (tan). The virus in the middle in cross section shows viral envelope proteins (red) studding the outer surface, with membrane proteins (pink) embedded in a fatty layer of lipids (light purples). In the innermost circle, you can see the viral genome (yellow) coiled around capsid proteins (orange).

This image was sketched and hand-painted with watercolors by David Goodsell, a researcher and illustrator at The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA. Goodsell put paint and science to paper as part of the “Molecule of the Month” series run by RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB), which NIH co-supports with the National Science Foundation and the Department of Energy. The PDB, which contains structural data on thousands of proteins and small molecules, uses its “Molecule of the Month” series to help students visualize a molecule or virus and to encourage their exploration of structural biology and its applications to medicine.

Portable System Uses Light to Diagnose Bacterial Infections Faster

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: PAD system. Left, four optical testing cubes (blue and white) stacked on the electronic base station (white with initials); right, a smartphone with a special app to receive test results transmitted by the electronic base station.

Credit: Park et al. Sci. Adv. 2016

Every year, hundreds of thousands of Americans acquire potentially life-threatening bacterial infections while in the hospital, nursing home, or other health-care settings [1]. Such infections can be caused by a variety of bacteria, which may respond quite differently to different antibiotics. To match a patient with the most appropriate antibiotic therapy, it’s crucial to determine as quickly as possible what type of bacteria is causing his or her infection. In an effort to improve that process, an NIH-funded team is working to develop a point-of-care system and smartphone app aimed at diagnosing bacterial infections in a faster, more cost-effective manner.

The portable new system, described recently in the journal Science Advances, uses a novel light-based method for detecting telltale genetic sequences from bacteria in bodily fluids, such as blood, urine, or drainage from a skin abscess. Testing takes place within small, optical cubes that, when placed on an electronic base station, deliver test results within a couple of hours via a simple readout sent directly to a smartphone [2]. When the system was tested on clinical samples from a small number of hospitalized patients, researchers found that not only did it diagnose bacterial infections about as accurately and more swiftly than current methods, but it was also cheaper. This new system can potentially also be used to test for the presence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and contamination of medical devices.

Cool Videos: Another Kind of Art Colony

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

As long as researchers have been growing bacteria on Petri dishes using a jelly-like growth medium called agar, they have been struck by the interesting colors and growth patterns that microbes can produce from one experiment to the next. In the 1920s, Sir Alexander Fleming, the Scottish biologist who discovered penicillin, was so taken by this phenomenon that he developed his own palette of bacterial “paints” that he used in his spare time to create colorful pictures of houses, ballerinas, and other figures on the agar [1].

As long as researchers have been growing bacteria on Petri dishes using a jelly-like growth medium called agar, they have been struck by the interesting colors and growth patterns that microbes can produce from one experiment to the next. In the 1920s, Sir Alexander Fleming, the Scottish biologist who discovered penicillin, was so taken by this phenomenon that he developed his own palette of bacterial “paints” that he used in his spare time to create colorful pictures of houses, ballerinas, and other figures on the agar [1].

Fleming’s enthusiasm for agar art lives on among the current generation of microbiologists. In this short video, the agar (yellow) is seeded with bacterial colonies and, through the magic of time-lapse photography, you can see the growth of the colonies into what appears to be a lovely bouquet of delicate flowers. This piece of living art, developing naturally by bacterial colony expansion over the course of a week or two, features members of three bacterial genera: Serratia (red), Bacillus (white), and Nesterenkonia (light yellow).

A Look Inside a Beating Heart Cell

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: Microtubules (blue) in a beating heart muscle cell, or cardiomyocyte. Credit: Lab of Ben Prosser, Ph.D., Perelman School of Medicine, University of PennsylvaniaYou might expect that scientists already know everything there is to know about how a healthy heart beats. But researchers have only recently had the tools to observe some of the dynamic inner workings of heart cells as they beat. Now an NIH-funded team has captured video to show that a component of a heart muscle cell called microtubules—long thought to be very rigid—serve an unexpected role as molecular shock absorbers.

As described for the first time recently in the journal Science, the microtubules buckle under the force of each contraction of the muscle cell before springing back to their original length and form. The team also details a biochemical process that allows a cell to fine-tune the level of resistance that the microtubules provide. The findings have important implications for understanding not only the mechanics of a healthy beating heart, but how the abnormal stiffening of heart cells might play a role in various forms of cardiac disease.