Zika vaccine

Tracing Spread of Zika Virus in the Americas

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: Here I am visiting the Ziika Forest area of Uganda, where the Zika virus was first identified in 1947.

Credit: National Institutes of Health

A couple of summers ago, the threat of mosquito-borne Zika virus disease in tropical areas of the Americas caused major concern, and altered the travel plans of many. The concern was driven by reports of Zika-infected women giving birth to babies with small heads and incompletely developed brains (microcephaly), as well as other serious birth defects. So, with another summer vacation season now upon us, you might wonder what’s become of Zika.

While pregnant women and couples planning on having kids should still take extra precautions [1] when travelling outside the country, the near-term risk of disease outbreaks has largely subsided because so many folks living in affected areas have already been exposed to the virus and developed protective immunity. But the Zika virus—first identified in the Ziika Forest in Uganda in 1947—has by no means been eliminated, making it crucial to learn more about how it spreads to avert future outbreaks. It’s very likely we have not heard the last of Zika in the Western hemisphere.

Recently, an international research team, partly funded by NIH, used genomic tools to trace the spread of the Zika virus. Genomic analysis can be used to build a “family tree” of viral isolates, and such analysis suggests that the first Zika cases in Central America were reported about a year after the virus had actually arrived and begun to spread.

The Zika virus, having circulated for decades in Africa and Asia before sparking a major outbreak in French Polynesia in 2013, slipped undetected across the Pacific Ocean into Brazil early in 2014, as established in previous studies. The new work reveals that by that summer, the bug had already hopped unnoticed to Honduras, spreading rapidly to other Central American nations and Mexico—likely by late 2014 and into 2015 [2].

Happy New Year: Looking Back at 2016 Research Highlights

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Happy New Year! While everyone was busy getting ready for the holidays, the journal Science announced its annual compendium of scientific Breakthroughs of the Year. If you missed it, the winner for 2016 was the detection of gravitational waves—tiny ripples in the fabric of spacetime created by the collision of two black holes 1.3 billion years ago! It’s an incredible discovery, and one that Albert Einstein predicted a century ago.

Happy New Year! While everyone was busy getting ready for the holidays, the journal Science announced its annual compendium of scientific Breakthroughs of the Year. If you missed it, the winner for 2016 was the detection of gravitational waves—tiny ripples in the fabric of spacetime created by the collision of two black holes 1.3 billion years ago! It’s an incredible discovery, and one that Albert Einstein predicted a century ago.

Among the nine other advances that made the first cut for Breakthrough of the Year, several involved the biomedical sciences. As I’ve done in previous years (here and here), I’ll kick off this New Year by taking a quick look of some of the breakthroughs that directly involved NIH support:

Treating Zika Infection: Repurposed Drugs Show Promise

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

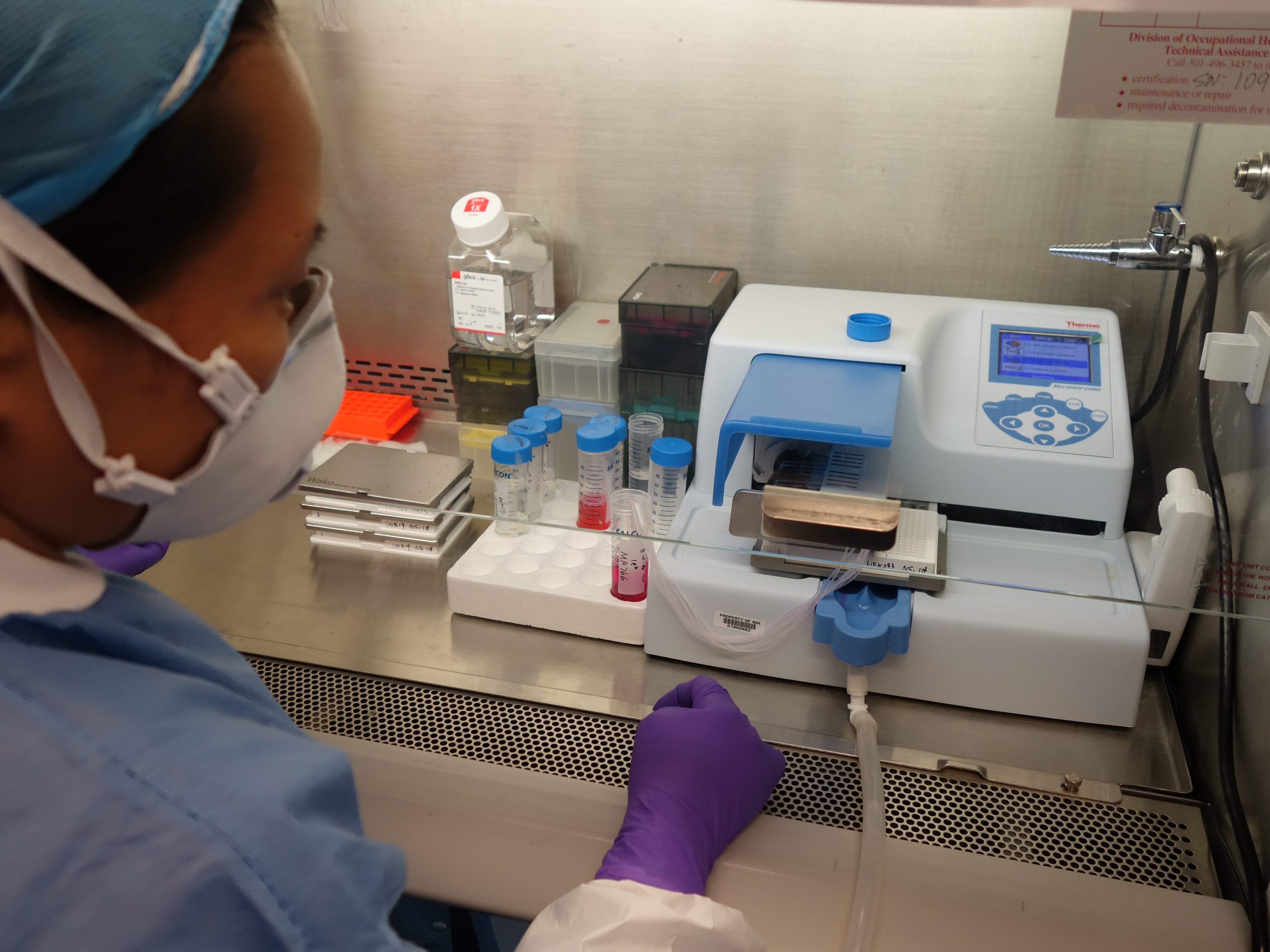

Credit: National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, NIH

In response to the health threat posed by the recent outbreak of Zika virus in Latin America and its recent spread to Puerto Rico and Florida, researchers have been working at a furious pace to learn more about the mosquito-borne virus. Considerable progress has been made in understanding how Zika might cause babies to be born with unusually small heads and other abnormalities and in developing vaccines that may guard against Zika infection.

Still, there remains an urgent need to find drugs that can be used to treat people already infected with the Zika virus. A team that includes scientists at NIH’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) now has some encouraging news on this front. By testing 6,000 FDA-approved drugs and experimental chemical compounds on Zika-infected human cells in the lab, they’ve shown that some existing drugs might be repurposed to fight Zika infection and prevent the virus from harming the developing brain [1]. While additional research is needed, the new findings suggest it may be possible to speed development and approval of new treatments for Zika infection.

Zika Vaccine: Two Candidates Show Promise in Mice

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

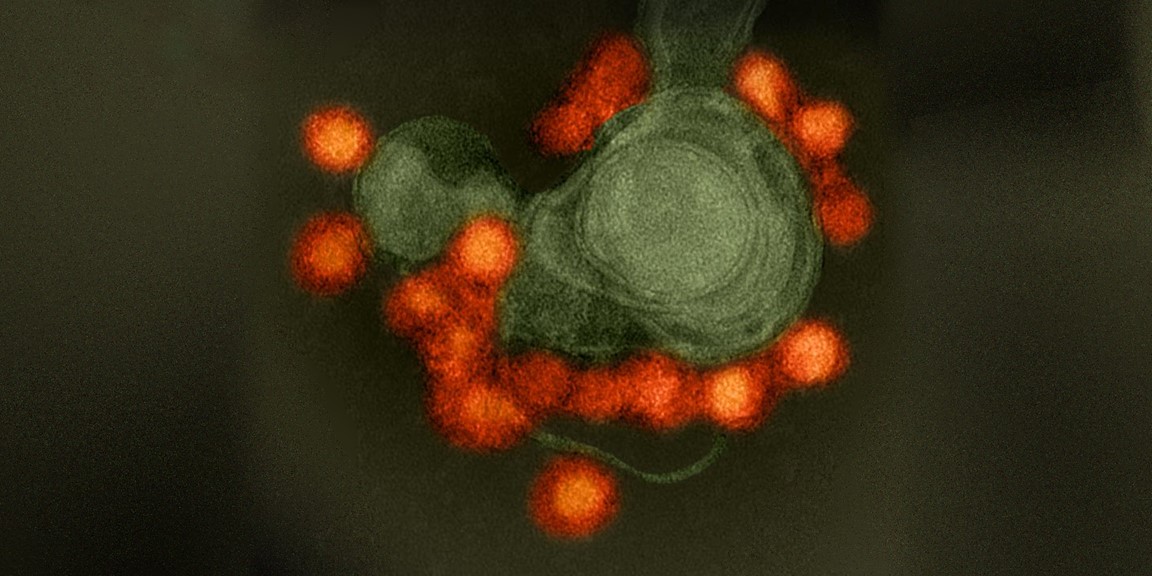

Caption: Zika virus (red), isolated from a microcephaly case in Brazil. The virus is associated with cellular membranes in the center.

Credit: NIAID

Last February, the World Health Organization declared a public health emergency over concerns about very serious birth defects in Brazil and their possible link to Zika virus. But even before then, concerns about the unprecedented spread of Zika virus in Brazil and elsewhere in Latin America had prompted NIH-funded scientists to step up their efforts to combat this emerging infectious disease threat. Over the last year, research aimed at understanding the mosquito-borne virus has progressed rapidly, and we now appear to be getting closer to a Zika vaccine.

In a recent study in the journal Nature, researchers found that a single dose of either of two experimental vaccines completely protected mice against a major viral strain responsible for the Zika outbreak in Brazil [1]. Caution is certainly warranted when extrapolating these (or any other) findings from mice to people. But, taking into account the fact that researchers have already developed safe and effective human vaccines for several related viruses, the new work represents a very encouraging milestone on the road toward a much-needed Zika vaccine for humans.

Snapshots of Life: Portrait of Zika Virus

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

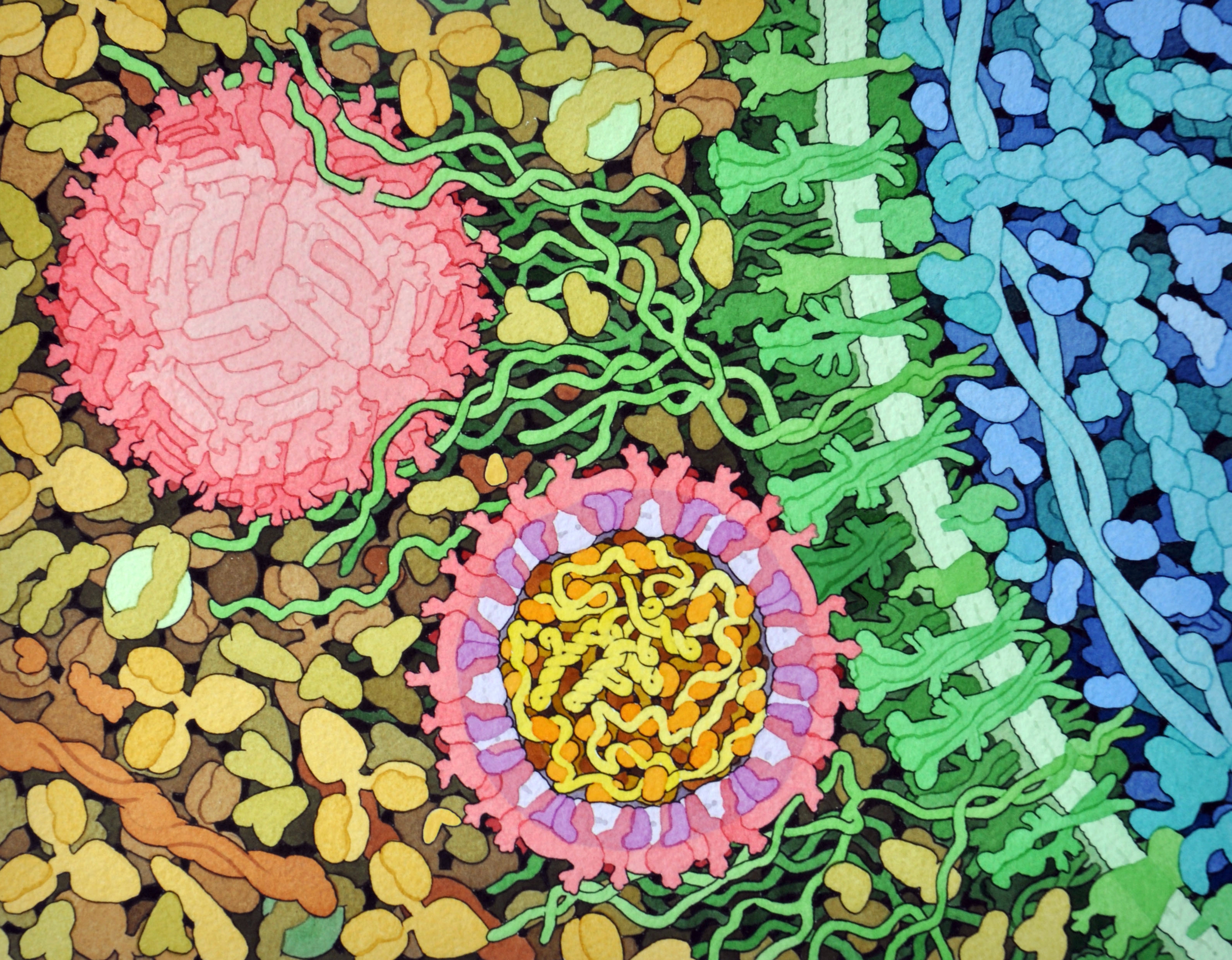

Credit: David Goodsell, The Scripps Research Institute

This lively interplay of shape and color is an artistic rendering of the Zika virus preparing to enter a cell (blue) by binding to its protein receptors (green). The spherical structures (pink) represent two Zika viruses in a blood vessel filled with blood plasma cells (tan). The virus in the middle in cross section shows viral envelope proteins (red) studding the outer surface, with membrane proteins (pink) embedded in a fatty layer of lipids (light purples). In the innermost circle, you can see the viral genome (yellow) coiled around capsid proteins (orange).

This image was sketched and hand-painted with watercolors by David Goodsell, a researcher and illustrator at The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA. Goodsell put paint and science to paper as part of the “Molecule of the Month” series run by RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB), which NIH co-supports with the National Science Foundation and the Department of Energy. The PDB, which contains structural data on thousands of proteins and small molecules, uses its “Molecule of the Month” series to help students visualize a molecule or virus and to encourage their exploration of structural biology and its applications to medicine.