2019 February

Thoughts from the Front Lines of Rare Disease Research

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

There are nearly 7,000 rare diseases, some of which affect just a few dozen people. Yet, if one considers all these conditions together, about 30 million people in the United States have rare diseases. On this Rare Disease Day, I’d like to challenge each of you to think about how we can raise the visibility of individuals living with rare diseases, as well as the researchers working hard to help them.

I’d like to introduce you to Harper Spero, who is using her rare gift of storytelling to share the experiences of people with a wide variety of conditions that she likes to call “invisible illnesses.” Through her podcast series, called Made Visible, this 34-year-old New York City native is among the many people helping to spread the word that rare diseases are not rare.

Spero knows what it’s like to live with a rare disease. Shortly after she was born, it became clear that she was unusually prone to infections. But doctors had a hard time figuring out what exactly was wrong with this little girl. Finally, at the age of 10, Spero was diagnosed with Hyper-Immunoglobulin E Syndrome (HIES), also known as Job’s syndrome. There currently is no cure for this rare genetic disease, which impairs the immune system and affects multiple parts of the body. But Spero is determined to live a normal life despite her chronic “invisible illness.”

Spero also knows what it’s like to take part in biomedical research. Seven years ago, she came to the NIH Clinical Center here in Bethesda, MD, seeking help for a large cyst in her right lung. It marked the beginning of a positive partnership with a Job’s syndrome research team led by two of NIH’s many dedicated physician-scientists, Alexandra Freeman and Steven Holland. Not only did the NIH researchers work with Spero to figure out the best ways of managing her symptoms, they are using what they’ve learned from her and about 175 other Job’s syndrome patients to develop approaches for earlier diagnosis and interventions. Spero, who visits the Clinical Center annually and communicates with the NIH team on a weekly basis, has been so inspired by the experience that she even chose to feature Dr. Freeman in one of her recent podcasts.

Unlike Spero, I don’t have a podcast—at least not yet. But I do have a blog, and Spero was kind enough to respond to a few of my questions on rare diseases and medical research. So, I’m sharing her thoughts below—I hope you are inspired by them as much as I was!

Why do you feel it is important for people with rare diseases to take part in medical research?

Without research, we can’t make any improvements, changes or find cures. Participating in medical research allows researchers and doctors to learn about the trends (or lack of) between patients, and determine what’s working and what’s not.

What have your own experiences been with the health-care system and medical research?

When I was younger, I really didn’t want to be a specimen. I was going through so much trying to find answers and treatments for myself that it was hard to think about how it would help other patients down the road to be sharing my experiences. I didn’t want to add another doctor’s visit to my schedule. After coming to NIH in 2012, I recognized the importance of being part of the research because it could essentially help me, other patients and for early detection of rare diseases. I recognize that the medical researchers are often much more compassionate than many doctors who simply treat symptoms. Researchers are curious and genuinely care to understand you and your story.

Your podcast is fantastic. How has it affected you to hear and share the stories of so many people affected by rare diseases?

I was definitely aware how many people were living with rare diseases, but I was surprised by how many people were willing to share their stories on my show and how many people wanted to listen to these stories. I hadn’t heard stories being shared in this way around this topic and I wanted to be the one who brought them to life. Many of my guests haven’t publicly (let alone with friends or family) shared their stories so I’m honored that they’re willing to do it with me. They see how important it is to have these conversations and to educate people on what it’s like to have an invisible illness.

What would you tell someone who’s just learned he or she has a rare disease?

You don’t have to do this alone! Find a team of medical professionals you trust to support you. I spent most of my life without a team of doctors that I loved and truly understood me, and now I can’t imagine my life without my team at NIH. Also, talk to your loved ones—let them know what you’re feeling and discuss how they can support you. This is likely new for them too and there’s no right way of navigating and managing a rare disease.

What would you tell a young person who’s considering becoming a rare disease researcher?

Thank you for your interest in doing this! We need more compassionate, curious and passionate people doing this work and investing their time to learn more and help find answers for rare diseases. Please treat us with respect and care.

If you could change one thing in the medical care/research of rare disease, what would it be? And what about in society in general?

There’s a way to do your job without treating patients like guinea pigs. We’re humans too, and we’re humans who have likely been through the wringer in the medical world. Be kind to us. Treat us the way you’d like to be treated. Compassion seems to be a word I’m using a lot. I think society can be more compassionate towards one another especially around rare disease. You can never fully understand what someone is going through so ask questions, show you care and treat people with kindness.

What are your hopes for the future?

I’d love there to be more answers and solutions for navigating a rare disease. A lot of the treatments I do are based on trial-and-error. What works for one patient definitely doesn’t always work for me. So, we’re constantly trying to navigate what works best for me. I’d love to see a cure to be found for Hyper IgE/Job’s Syndrome, as well as other rare diseases.

Links:

Podcast Series: Made Visible

NIH Patient Shares Stories of ‘Invisible Illness,’ The NIH Record, February 8, 2019

Hyper-Immunoglobulin E Syndrome (HIES) (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases/NIH)

Rare Disease Day at NIH 2019 (National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences/NIH)

Rare Diseases Are Not Rare! Challenge Offers New Tools to Raise Awareness. January 2019 (NCATS)

Video: Rare Disease Patient Profiles (NCATS)

Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (NCATS)

Undiagnosed Diseases Network (Common Fund/NIH)

Video: One in a Million (Undiagnosed Diseases Network, University of Utah Health, Salt Lake City)

More Progress Toward Gene Editing for Kids with Muscular Dystrophy

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Thanks to CRISPR and other gene editing technologies, hopes have never been greater for treating or even curing Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) and many other rare, genetic diseases that once seemed tragically out of reach. The latest encouraging news comes from a study in which a single infusion of a CRISPR editing system produced lasting benefits in a mouse model of DMD.

There currently is no way to cure DMD, an ultimately fatal disease that mainly affects boys. Caused by mutations in a gene that codes for a critical protein called dystrophin, DMD progressively weakens the skeletal and heart muscles. People with DMD are usually in wheelchairs by the age of 10, with most dying before the age of 30.

The exquisite targeting ability of CRISPR/Cas9 editing systems rely on a sequence-specific guide RNA to direct a scissor-like, bacterial enzyme (Cas9) to just the right spot in the genome, where it can be used to cut out, replace, or repair disease-causing mutations. In previous studies in mice and dogs, researchers directly infused CRISPR systems directly into the animals bodies. This “in vivo” approach to gene editing successfully restored production of functional dystrophin proteins, strengthening animals’ muscles within weeks of treatment.

But an important question remained: would CRISPR’s benefits persist over the long term? The answer in a mouse model of DMD appears to be “yes,” according to findings published recently in Nature Medicine by Charles Gersbach, Duke University, Durham, NC, and his colleagues [1]. Specifically, the NIH-funded team found that after mice with DMD received one infusion of a specially designed CRISPR/Cas9 system, the abnormal gene was edited in a way that restored dystrophin production in skeletal and heart muscles for more than a year. What’s more, lasting improvements were seen in the structure of the animals’ muscles throughout the same time period.

As exciting as these results may be, much more research is needed to explore both the safety and the efficacy of in vivo gene editing before it can be tried in humans with DMD. For instance, the researchers found that older mice that received the editing system developed an immune response to the bacterially-derived Cas9 protein. However, this response didn’t prevent the CRISPR/Cas9 system from doing its job or appear to cause any adverse effects. Interestingly, younger animals didn’t show such a response.

It’s worth noting that the immune systems of mice and people often respond quite differently. But the findings do highlight some possible challenges of such treatments, as well as approaches to reduce possible side effects. For instance, the latest findings suggest CRISPR/Cas9 treatment might best be done early in life, before an infant’s immune system is fully developed. Also, if it’s necessary to deliver CRISPR/Cas9 to older individuals, it may be beneficial to suppress the immune system temporarily.

Another concern about CRISPR technology is the potential for damaging, “off-target” edits to other parts of the genome. In the new work, the Duke team found that its CRISPR system made very few “off-target” edits. However, the system did make a surprising number of complex edits to the targeted dystrophin gene, including integration of the viral vector used to deliver Cas9. While those editing “errors” might reduce the efficacy of treatment, researchers said they didn’t appear to affect the health of the mice studied.

It’s important to emphasize that this gene editing research aimed at curing DMD is being done in non-reproductive (somatic) cells, primarily muscle tissue. The NIH does not support the use of gene editing technologies in human embryos or human reproductive (germline) cells, which would change the genetic makeup of future offspring.

As such, the Duke researchers’ CRISPR/Cas9 system is designed to work optimally in a range of muscle and muscle-progenitor cells. Still, they were able to detect editing of the dystrophin-producing gene in the liver, kidney, brain, and other tissues. Importantly, there was no evidence of edits in the germline cells of the mice. The researchers note that their CRISPR system can be reconfigured to limit gene editing to mature muscle cells, although that may reduce the treatment’s efficacy.

It’s truly encouraging to see that CRISPR gene editing may confer lasting benefits in an animal model of DMD, but a great many questions remain before trying this new approach in kids with DMD. But that time is coming—so let’s boldly go forth and get answers to those questions on behalf of all who are affected by this heartbreaking disease.

Reference:

[1] Long-term evaluation of AAV-CRISPR genome editing for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nelson CE, Wu Y, Gemberling MP, Oliver ML, Waller MA, Bohning JD, Robinson-Hamm JN, Bulaklak K, Castellanos Rivera RM, Collier JH, Asokan A, Gersbach CA. Nat Med. 2019 Feb 18.

Links:

Muscular Dystrophy Information Page (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke/NIH)

Gersbach Lab (Duke University, Durham, NC)

Somatic Cell Genome Editing (Common Fund/NIH)

NIH Support: National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases; National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering

Students Contribute to Research Through Ovarian Art

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Seeing the development of an organ under a microscope for the first time can be a truly unforgettable experience. But for a class taught by Crystal Rogers at California State University, Northridge, it can also be an award-winning moment.

This image, prepared during a biology lab course, was one of the winners in the 2018 BioArt Scientific Image & Video Competition, sponsored by the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology (FASEB). This colorful image shows the tip of an ovary from a fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster), provided by Mariano Loza-Coll. You can see that the ovary is packed with oocytes (DNA stained blue). The orderly connective structure (pink) and signal-transmitting molecules like STAT (yellow) are common to egg maturation and reproductive processes in humans.

What makes this image unique among this year’s BioArt winners is that the prep work was done by undergraduate students just learning how to work in a lab. They did the tissue dissections, molecular labeling, and beautiful stainings in preparation for Rogers to “snap” the photo on her research lab’s optical-sectioning microscope.

What’s also fantastic is that many of Rogers’s students are from groups traditionally underrepresented in biomedicine. Many are considering careers in research and, from the looks of things, they are off to a beautiful start.

After teaching classes, Rogers also has an NIH-supported lab to run. She and her team study salamanders and chickens to determine how biological “glue” proteins, called cadherins, help to create neural crest cells, a critical cell type that arises very early in development [1].

For developmental biologists, it’s essential to understand what prompts these neural crest cells to migrate to locations throughout the body, from the heart to the skin to the cranium, or head. For example, cranial neural crest cells at first produce what appears to be the same generic, undifferentiated facial template in vertebrate species. And yet, neural crest cells and the surrounding ectodermal cells go on to generate craniofacial structures as distinct as the beak of a toucan, the tusk of a boar, or the horn of a rhinoceros.

But if the organ of interest is an ovary, the fruit fly has long been a go-to organism to learn more. Not only does the fruit fly open a window into ovarian development and health issues like infertility, it showcases the extraordinary beauty of biology.

Reference:

[1] A catenin-dependent balance between N-cadherin and E-cadherin controls neuroectodermal cell fate choices. Rogers CD, Sorrells LK, Bronner ME. Mech Dev. 2018 Aug;152:44-56.

Links:

Rogers Lab (California State University, Northridge)

BioArt Scientific Image & Video Competition (Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology, Bethesda, MD)

NIH Support: Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development

Serenading the Scientists of Tomorrow

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Oral Insulin Delivery: Can the Tortoise Win the Race?

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

People with diabetes often must inject insulin multiple times a day to keep their blood glucose levels under control. So, I was intrigued to learn that NIH-funded bioengineers have designed a new kind of “pill” that may someday reduce the need for those uncomfortable shots. The inspiration for their design? A tortoise!

The new “pill”—actually, a swallowable device containing a tiny injection system—is shaped like the shell of an African leopard tortoise. In much the same way that the animal’s highly curved shell enables it to quickly right itself when flipped on its back, the shape of the new device is intended to help it land in the right position to inject insulin or other medicines into the stomach wall.

The hunt for a means to deliver insulin in pill form has been on ever since insulin injections first were introduced, nearly a century ago. The challenge in oral delivery of insulin and other “biologic” drugs—including therapeutic proteins, peptides, or nucleic acids—is how to get these large biomolecules through the highly acidic stomach and duodenum, where multiple powerful digestive enzymes reside, and into the bloodstream unscathed. Past efforts to address this challenge have met with only limited success.

In a study published in the journal Science, a team, led by Robert Langer at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, and Giovanni Traverso, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, took a new approach to the problem by developing a tiny, ingestible injection system [1]. They call their pea-sized device SOMA, short for “self-orienting millimeter-scale applicator.”

In designing SOMA, the researchers knew they had to come up with a design that would orient the injection apparatus correctly. So they looked to the African leopard tortoise. They knew that, much like a child’s “weeble-wobble” toy, this tortoise can easily right its body if tipped over due to its low center of gravity and highly curved shell. With the shape of the tortoise shell as a starting point, the researchers used computer modeling to perfect their design. The final result features a partially hollowed-out, polymer-and-steel capsule that houses a tiny, spring-loaded needle tipped with compressed, freeze-dried insulin. There is also a dissolvable sugar disk to hold the needle in place until the time is right.

Here’s how it works: once a SOMA is swallowed and reaches the stomach, it quickly orients itself in a way that its needle-side rests against the stomach wall. After the protective sugar disk dissolves in stomach acid, the spring-loaded needle tipped with insulin is released, injecting its load of insulin into the stomach wall, from which it enters the bloodstream. Meanwhile, the spent SOMA device passes on through the digestive system.

The researchers’ tests in pigs have shown that a single SOMA can successfully deliver insulin doses of up to 3 milligrams, comparable to the amount a human with diabetes might need to inject. The tests also showed that the device’s microinjection did not damage the animals’ stomach tissue or the muscles surrounding the stomach. Because the stomach is known for being insensitive to pain, researchers expect that people receiving insulin via SOMA wouldn’t feel a thing, but much more research is needed to confirm both the safety and efficacy of the new device for human use.

Meanwhile, this fascinating work serves as a reminder that when it comes to biomedical science, inspiration sometimes can come from the most unexpected places.

Reference:

[1] An ingestible self-orienting system for oral delivery of macromolecules. Abramson A, Caffarel-Salvador E, Khang M, Dellal D, Silverstein D, Gao Y, Frederiksen MR, Vegge A, Hubálek F, Water JJ, Friderichsen AV, Fels J, Kirk RK, Cleveland C, Collins J, Tamang S, Hayward A, Landh T, Buckley ST, Roxhed N, Rahbek U, Langer R, Traverso G. Science. 2019 Feb 8;363(6427):611-615.

Links:

Diabetes (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases/NIH)

Langer Lab (MIT, Cambridge)

Giovanni Traverso (Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston)

NIH Support: National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering

Skin Cells Can Be Reprogrammed In Vivo

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Thousands of Americans are rushed to the hospital each day with traumatic injuries. Daniel Gallego-Perez hopes that small chips similar to the one that he’s touching with a metal stylus in this photo will one day be a part of their recovery process.

The chip, about one square centimeter in size, includes an array of tiny channels with the potential to regenerate damaged tissue in people. Gallego-Perez, a researcher at The Ohio State University Colleges of Medicine and Engineering, Columbus, has received a 2018 NIH Director’s New Innovator Award to develop the chip to reprogram skin and other cells to become other types of tissue needed for healing. The reprogrammed cells then could regenerate and restore injured neural or vascular tissue right where it’s needed.

Gallego-Perez and his Ohio State colleagues wondered if it was possible to engineer a device placed on the skin that’s capable of delivering reprogramming factors directly into cells, eliminating the need for the viral delivery vectors now used in such work. While such a goal might sound futuristic, Gallego-Perez and colleagues offered proof-of-principle last year in Nature Nanotechnology that such a chip can reprogram skin cells in mice. [1]

Here’s how it works: First, the chip’s channels are loaded with specific reprogramming factors, including DNA or proteins, and then the chip is placed on the skin. A small electrical current zaps the chip’s channels, driving reprogramming factors through cell membranes and into cells. The process, called tissue nanotransfection (TNT), is finished in milliseconds.

To see if the chips could help heal injuries, researchers used them to reprogram skin cells into vascular cells in mice. Not only did the technology regenerate blood vessels and restore blood flow to injured legs, the animals regained use of those limbs within two weeks of treatment.

The researchers then went on to show that they could use the chips to reprogram mouse skin cells into neural tissue. When proteins secreted by those reprogrammed skin cells were injected into mice with brain injuries, it helped them recover.

In the newly funded work, Gallego-Perez wants to take the approach one step further. His team will use the chip to reprogram harder-to-reach tissues within the body, including peripheral nerves and the brain. The hope is that the device will reprogram cells surrounding an injury, even including scar tissue, and “repurpose” them to encourage nerve repair and regeneration. Such an approach may help people who’ve suffered a stroke or traumatic nerve injury.

If all goes well, this TNT method could one day fill an important niche in emergency medicine. Gallego-Perez’s work is also a fine example of just one of the many amazing ideas now being pursued in the emerging field of regenerative medicine.

Reference:

[1] Topical tissue nano-transfection mediates non-viral stroma reprogramming and rescue. Gallego-Perez D, Pal D, Ghatak S, Malkoc V, Higuita-Castro N, Gnyawali S, Chang L, Liao WC, Shi J, Sinha M, Singh K, Steen E, Sunyecz A, Stewart R, Moore J, Ziebro T, Northcutt RG, Homsy M, Bertani P, Lu W, Roy S, Khanna S, Rink C, Sundaresan VB, Otero JJ, Lee LJ, Sen CK. Nat Nanotechnol. 2017 Oct;12(10):974-979.

Links:

Stroke Information (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke/NIH)

Burns and Traumatic Injury (NIH)

Peripheral Neuropathy (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke/NIH)

Video: Breakthrough Device Heals Organs with a Single Touch (YouTube)

Gallego-Perez Lab (The Ohio State University College of Medicine, Columbus)

Gallego-Perez Project Information (NIH RePORTER)

NIH Support: Common Fund; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

Meeting with Students at Johns Hopkins University

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Discovering a Source of Laughter in the Brain

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

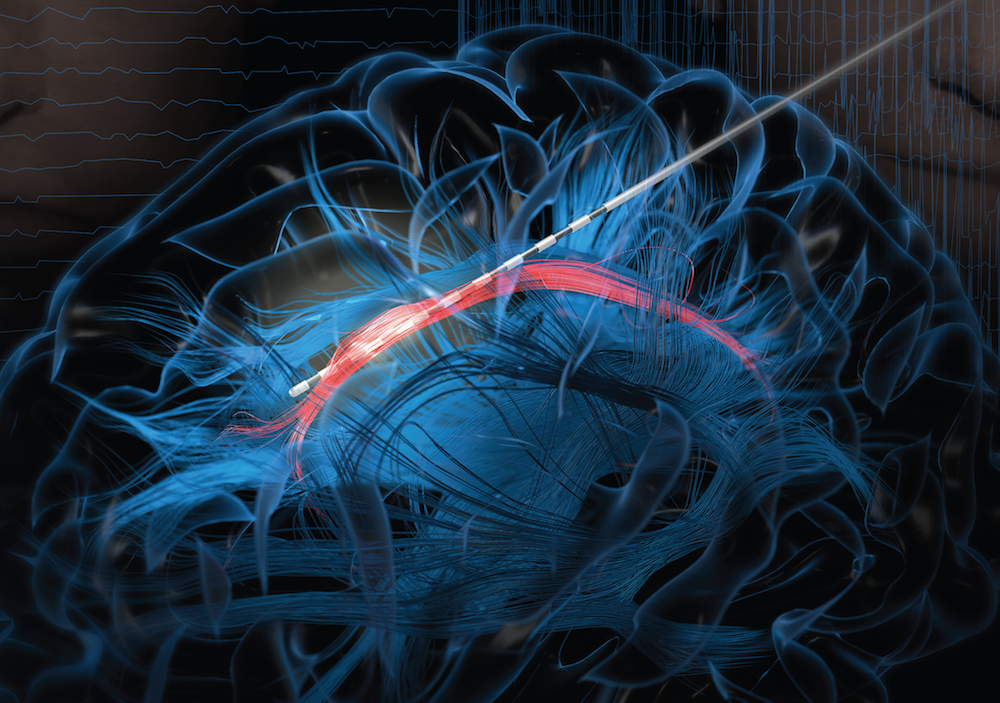

If laughter really is the best medicine, wouldn’t it be great if we could learn more about what goes on in the brain when we laugh? Neuroscientists recently made some major progress on this front by pinpointing a part of the brain that, when stimulated, never fails to induce smiles and laughter.

In their study conducted in three patients undergoing electrical stimulation brain mapping as part of epilepsy treatment, the NIH-funded team found that stimulation of a specific tract of neural fibers, called the cingulum bundle, triggered laughter, smiles, and a sense of calm. Not only do the findings shed new light on the biology of laughter, researchers hope they may also lead to new strategies for treating a range of conditions, including anxiety, depression, and chronic pain.

In people with epilepsy whose seizures are poorly controlled with medication, surgery to remove seizure-inducing brain tissue sometimes helps. People awaiting such surgeries must first undergo a procedure known as intracranial electroencephalography (iEEG). This involves temporarily placing 10 to 20 arrays of tiny electrodes in the brain for up to several weeks, in order to pinpoint the source of a patient’s seizures in the brain. With the patient’s permission, those electrodes can also enable physician-researchers to stimulate various regions of the patient’s brain to map their functions and make potentially new and unexpected discoveries.

In the new study, published in The Journal of Clinical Investigation, Jon T. Willie, Kelly Bijanki, and their colleagues at Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, looked at a 23-year-old undergoing iEEG for 8 weeks in preparation for surgery to treat her uncontrolled epilepsy [1]. One of the electrodes implanted in her brain was located within the cingulum bundle and, when that area was stimulated for research purposes, the woman experienced an uncontrollable urge to laugh. Not only was the woman given to smiles and giggles, she also reported feeling relaxed and calm.

As a further and more objective test of her mood, the researchers asked the woman to interpret the expression of faces on a computer screen as happy, sad, or neutral. Electrical stimulation to the cingulum bundle led her to see those faces as happier, a sign of a generally more positive mood. A full evaluation of her mental state also showed she was fully aware and alert.

To confirm the findings, the researchers looked to two other patients, a 40-year-old man and a 28-year-old woman, both undergoing iEEG in the course of epilepsy treatment. In those two volunteers, stimulation of the cingulum bundle also triggered laughter and reduced anxiety with otherwise normal cognition.

Willie notes that the cingulum bundle links many brain areas together. He likens it to a super highway with lots of on and off ramps. He suspects the spot they’ve uncovered lies at a key intersection, providing access to various brain networks regulating mood, emotion, and social interaction.

Previous research has shown that stimulation of other parts of the brain can also prompt patients to laugh. However, what makes stimulation of the cingulum bundle a particularly promising approach is that it not only triggers laughter, but also reduces anxiety.

The new findings suggest that stimulation of the cingulum bundle may be useful for calming patients’ anxieties during neurosurgeries in which they must remain awake. In fact, Willie’s team did so during their 23-year-old woman’s subsequent epilepsy surgery. Each time she became distressed, the stimulation provided immediate relief. Also, if traditional deep brain stimulation or less invasive means of brain stimulation can be developed and found to be safe for long-term use, they may offer new ways to treat depression, anxiety disorders, and/or chronic pain.

Meanwhile, Willie’s team is hard at work using similar approaches to map brain areas involved in other aspects of mood, including fear, sadness, and anxiety. Together with the multidisciplinary work being mounted by the NIH-led BRAIN Initiative, these kinds of studies promise to reveal functionalities of the human brain that have previously been out of reach, with profound consequences for neuroscience and human medicine.

Reference:

[1] Cingulum stimulation enhances positive affect and anxiolysis to facilitate awake craniotomy. Bijanki KR, Manns JR, Inman CS, Choi KS, Harati S, Pedersen NP, Drane DL, Waters AC, Fasano RE, Mayberg HS, Willie JT. J Clin Invest. 2018 Dec 27.

Links:

Video: Patient’s Response (Bijanki et al. The Journal of Clinical Investigation)

Epilepsy Information Page (National Institute of Neurological Disease and Stroke/NIH)

Jon T. Willie (Emory University, Atlanta, GA)

NIH Support: National Institute of Neurological Disease and Stroke; National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences

Mammalian Brain Like You’ve Never Seen It Before

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: Gao et. al, Science

Researchers are making amazing progress in developing new imaging approaches. And they are now using one of their latest creations, called ExLLSM, to provide us with jaw-dropping views of a wide range of biological systems, including the incredibly complex neural networks within the mammalian brain.

In this video, ExLLSM takes us on a super-resolution, 3D voyage through a tiny sample (0.0030 inches thick) from the part of the mouse brain that processes sensation, the primary somatosensory cortex. The video zooms in and out of densely packed pyramidal neurons (large yellow cell bodies), each of which has about 7,000 synapses, or connections. You can also see presynapses (cyan), the part of the neuron that sends chemical signals; and postsynapes (magenta), the part of the neuron that receives chemical signals.

At 1:45, the video zooms in on dendritic spines, which are mushroom-like nubs on the neuronal branches (yellow). These structures, located on the tips of dendrites, receive incoming signals that are turned into electrical impulses. While dendritic spines have been imaged in black and white with electron microscopy, they’ve never been presented before on such a vast, colorful scale.

The video comes from a paper, published recently in the journal Science [1], from the labs of Ed Boyden, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, and the Nobel Prize-winning Eric Betzig, Janelia Research Campus of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Ashburn, VA. Like many collaborations, this one comes with a little story.

Four years ago, the Boyden lab developed expansion microscopy (ExM). The technique involves infusing cells with a hydrogel, made from a chemical used in disposable diapers. The hydrogel expands molecules within the cell away from each other, usually by about 4.5 times, but still locks them into place for remarkable imaging clarity. It makes structures visible by light microscopy that are normally below the resolution limit.

Though the expansion technique has worked well with a small number of cells under a standard light microscope, it hasn’t been as successful—until now—at imaging thicker tissue samples. That’s because thicker tissue is harder to illuminate, and flooding the specimen with light often bleaches out the fluorescent markers that scientists use to label proteins. The signal just fades away.

For Boyden, that was a problem that needed to be solved. Because his lab’s goal is to trace the inner workings of the brain in unprecedented detail, Boyden wants to image entire neural circuits in relatively thick swaths of tissue, not just look at individual cells in isolation.

After some discussion, Boyden’s team concluded that the best solution might be to swap out the light source for the standard microscope with a relatively new imaging tool developed in the Betzig lab. It’s called lattice light-sheet microscopy (LLSM), and the tool generates extremely thin sheets of light that illuminate tissue only in a very tightly defined plane, dramatically reducing light-related bleaching of fluorescent markers in the tissue sample. This allows LLSM to extend its range of image acquisition and quickly deliver stunningly vivid pictures.

Telephone calls were made, and the Betzig lab soon welcomed Ruixuan Gao, Shoh Asano, and colleagues from the Boyden lab to try their hand at combining the two techniques. As the video above shows, ExLLSM has proved to be a perfect technological match. In addition to the movie above, the team has used ExLLSM to provide unprecedented views of a range of samples—from human kidney to neuron bundles in the brain of the fruit fly.

Not only is ExLLSM super-resolution, it’s also super-fast. In fact, the team imaged the entire fruit fly brain in 2 1/2 days—an effort that would take years using an electron microscope.

ExLLSM will likely never supplant the power of electron microscopy or standard fluorescent light microscopy. Still, this new combo imaging approach shows much promise as a complementary tool for biological exploration. The more innovative imaging approaches that researchers have in their toolbox, the better for our ongoing efforts to unlock the mysteries of the brain and other complex biological systems. And yes, those systems are all complex. This is life we’re talking about!

Reference:

[1] Cortical column and whole-brain imaging with molecular contrast and nanoscale resolution. Gao R, Asano SM, Upadhyayula S, Pisarev I, Milkie DE, Liu TL, Singh V, Graves A, Huynh GH, Zhao Y, Bogovic J, Colonell J, Ott CM, Zugates C, Tappan S, Rodriguez A, Mosaliganti KR, Sheu SH, Pasolli HA, Pang S, Xu CS, Megason SG, Hess H, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Hantman A, Rubin GM, Kirchhausen T, Saalfeld S, Aso Y, Boyden ES, Betzig E. Science. 2019 Jan 18;363(6424).

Links:

Video: Expansion Microscopy Explained (YouTube)

Video: Lattice Light-Sheet Microscopy (YouTube)

How to Rapidly Image Entire Brains at Nanoscale Resolution, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, January 17, 2019.

Synthetic Neurobiology Group (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge)

Eric Betzig (Janelia Reseach Campus, Ashburn, VA)

NIH Support: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; National Human Genome Research Institute; National Institute on Drug Abuse; National Institute of Mental Health; National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering

Next Page