Alzheimer’s disease

Connecting Senescent Cells to Obesity and Anxiety

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Obesity—which affects about 4 in 10 U.S. adults—increases the risk for lots of human health problems: diabetes, heart disease, certain cancers, and even anxiety and depression [1]. It’s also been associated with increased accumulation of senescent cells, which are older cells that resist death even as they lose the ability to grow and divide.

Now, NIH-funded researchers have found that when lean mice are fed a high-fat diet that makes them obese, they also have more senescent cells in their brain and show more anxious behaviors [2]. The researchers could reduce this obesity-driven anxiety using so-called senolytic drugs that cleared away the senescent cells. These findings are among the first to provide proof-of-concept that senolytics may offer a new avenue for treating an array of neuropsychiatric disorders, in addition to many other chronic conditions.

As we age, senescent cells accumulate in many parts of the body [3]. But cells can also enter a senescent state at any point in life in response to major stresses, such as DNA damage or chronic infection. Studies suggest that having lots of senescent cells around, especially later in life, is associated with a wide variety of chronic conditions, including osteoporosis, osteoarthritis, vascular disease, and general frailty.

Senescent cells display a “zombie”-like behavior known as a senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP). In this death-defying, zombie-like state, the cells ramp up their release of proteins, bioactive lipids, DNA, and other factors that, like a zombie virus, induce nearby healthy cells to join in the dysfunction.

In fact, the team behind this latest study, led by James Kirkland, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, recently showed that transplanting small numbers of senescent cells into young mice is enough to cause them weakness, frailty, and persistent health problems. Those ill effects were alleviated with a senolytic cocktail, including dasatinib (a leukemia drug) and quercetin (a plant compound). This drug cocktail overrode the zombie-like SASP phenotype and forced the senescent cells to undergo programmed cell death and finally die.

Previous research indicates that senescent cells also accumulate in obesity, and not just in adipose tissues. Moreover, recent studies have linked senescent cells in the brain to neurodegenerative conditions, including Alzheimer’s disease, and showed in mice that dasatinib and quercetin helps to alleviate neurodegenerative disease [4,5]. In the latest paper, published in the journal Cell Metabolism, Kirkland and colleagues asked whether senescent cells in the brain also could explain anxiety-like behavior in obesity.

The answer appears to be “yes.” The researchers showed that lean mice, if allowed to feast on a high-fat diet, grew obese and became more anxious about exploring open spaces and elevated mazes.

The researchers also found that the obese mice had an increase in senescent cells in the white matter near the lateral ventricle, a part of the brain that offers a pathway for cerebrospinal fluid. Those senescent cells also contained an excessive amount of fat. Could senolytic drugs clear those cells and make the obesity-related anxiety go away?

To find out, the researchers treated lean and obese mice with a senolytic drug for 10 weeks. The treatment didn’t lead to any changes in body weight. But, as senescent cells were cleared from their brains, the obese mice showed a significant reduction in their anxiety-related behavior. They lost their anxiety without losing the weight!

More preclinical study is needed to understand more precisely how the treatment works. But, it’s worth noting that clinical trials testing a variety of senolytic drugs are already underway for many conditions associated with senescent cells, including chronic kidney disease [6,7], frailty [8], and premature aging associated with bone marrow transplant [9].

As a matter of fact, just after the Cell Metabolism paper came out, Kirkland’s team published encouraging though preliminary, first-in-human results of the previously mentioned senolytic drug dasatinib in 14 people with age-related idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, a condition in which lung tissue becomes damaged and scarred [10]. Caution is warranted as we learn more about the associated risks and benefits, but it’s safe to say we’ll be hearing a lot more about senolytics in the years ahead.

References:

[1] Adult obesity facts (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

[2] Obesity-induced cellular senescence drives anxiety and impairs neurogenesis. Ogrodnik M et al. Cell Metabolism. 2019 Jan 3.

[3] Aging, Cell Senescence, and Chronic Disease: Emerging Therapeutic Strategies. Tchkonia T, Kirkland JL. JAMA. 2018 Oct 2;320(13):1319-1320.

[4] Tau protein aggregation is associated with cellular senescence in the brain. Musi N, Valentine JM, Sickora KR, Baeuerle E, Thompson CS, Shen Q, Orr ME. Aging Cell. 2018 Dec;17(6):e12840.

[5] Clearance of senescent glial cells prevents tau-dependent pathology and cognitive decline. Bussian TJ, Aziz A, Meyer CF, Swenson BL, van Deursen JM, Baker DJ. Nature. 2018 Oct;562(7728):578-582.

[6] Inflammation and Stem Cells in Diabetic and Chronic Kidney Disease. ClinicalTrials.gov, Sep 2018.

[7] Senescence in Chronic Kidney Disease. Clinicaltrials.gov, Sep 2018.

[8] Alleviation by Fisetin of Frailty, Inflammation, and Related Measures in Older Adults (AFFIRM-LITE). Clinicaltrials.gov, Dec 2018.

[9] Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant Survivors Study (HTSS Study). Clinicaltrials.gov, Sep 2018.

[10] Senolytics in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: Results from a first-in-human, open-label, pilot study. Justice JN, Nambiar AN, Tchkonia T, LeBrasseur K, Pascual R, Hashmi SK, Prata L, Masternak MM, Kritchevsky SB, Musi N, Kirkland JL. EBioMed. 5 Jan. 2019. [Epub ahead of print]

Links:

Healthy Aging (National Institute on Aging/NIH)

Video: Vail Scientific Summit James Kirkland Interview (Youtube)

James Kirkland (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN)

NIH Support: National Institute on Aging; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

A New Piece of the Alzheimer’s Puzzle

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: National Institute on Aging, NIH

For the past few decades, researchers have been busy uncovering genetic variants associated with an increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [1]. But there’s still a lot to learn about the many biological mechanisms that underlie this devastating neurological condition that affects as many as 5 million Americans [2].

As an example, an NIH-funded research team recently found that AD susceptibility may hinge not only upon which gene variants are present in a person’s DNA, but also how RNA messages encoded by the affected genes are altered to produce proteins [3]. After studying brain tissue from more than 450 deceased older people, the researchers found that samples from those with AD contained many more unusual RNA messages than those without AD.

Talking about Alzheimer’s Issues with CBS’s Jon LaPook

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Enjoyed my one-on-one exchange with Dr. Jonathan LaPook, CBS Evening News medical correspondent. We talked during the Alzheimer’s Impact Movement (AIM) Advocacy Forum on June 18, 2018 in Washington, D.C. The event was sponsored by the Alzheimer’s Association. Credit: Alzheimer’s Association

Teaching Computers to “See” the Invisible in Living Cells

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: Steven Finkbeiner, University of California, San Francisco and the Gladstone Institutes

For centuries, scientists have trained themselves to look through microscopes and carefully study their structural and molecular features. But those long hours bent over a microscope poring over microscopic images could be less necessary in the years ahead. The job of analyzing cellular features could one day belong to specially trained computers.

In a new study published in the journal Cell, researchers trained computers by feeding them paired sets of fluorescently labeled and unlabeled images of brain tissue millions of times in a row [1]. This allowed the computers to discern patterns in the images, form rules, and apply them to viewing future images. Using this so-called deep learning approach, the researchers demonstrated that the computers not only learned to recognize individual cells, they also developed an almost superhuman ability to identify the cell type and whether a cell was alive or dead. Even more remarkable, the trained computers made all those calls without any need for harsh chemical labels, including fluorescent dyes or stains, which researchers normally require to study cells. In other words, the computers learned to “see” the invisible!

Snapshots of Life: The Birth of New Neurons

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

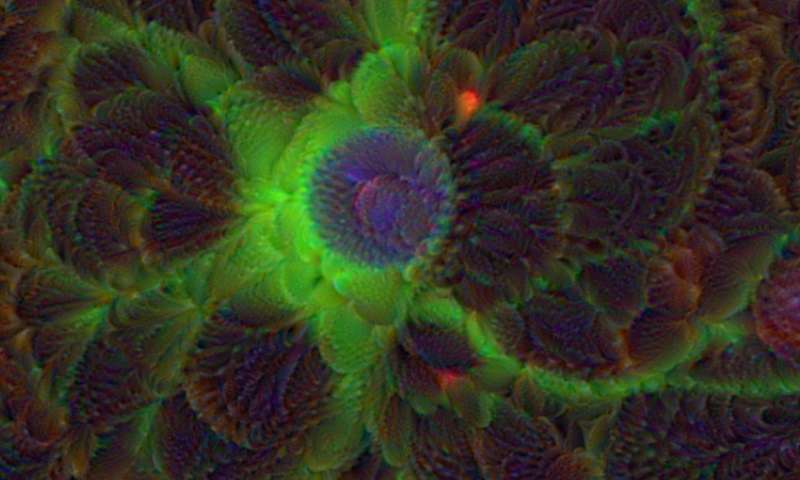

After a challenging day at work or school, sometimes it may seem like you are down to your last brain cell. But have no fear—in actuality, the brains of humans and other mammals have the potential to produce new neurons throughout life. This remarkable ability is due to a specific type of cell—adult neural stem cells—so beautifully highlighted in this award-winning micrograph.

Here you see the nuclei (purple) and arm-like extensions (green) of neural stem cells, along with nuclei of other cells (blue), in brain tissue from a mature mouse. The sample was taken from the subgranular zone of the hippocampus, a region of the brain associated with learning and memory. This zone is also one of the few areas in the adult brain where stem cells are known to reside.

Snapshots of Life: Growing Mini-Brains in a Dish

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Something pretty incredible happens—both visually and scientifically—when researchers spread neural stem cells onto a gel-like matrix in a lab dish and wait to see what happens. Gradually, the cells differentiate and self-assemble to form cohesive organoids that resemble miniature brains!

In this image of a mini-brain organoid, the center consists of a clump of neuronal bodies (magenta), surrounded by an intricate network of branching extensions (green) through which these cells relay information. Scattered throughout the mini-brain are star-shaped astrocytes (red) that serve as support cells.

Creative Minds: Using Machine Learning to Understand Genome Function

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Science has always fascinated Anshul Kundaje, whether it was biology, physics, or chemistry. When he left his home country of India to pursue graduate studies in electrical engineering at Columbia University, New York, his plan was to focus on telecommunications and computer networks. But a course in computational genomics during his first semester showed him he could follow his interest in computing without giving up his love for biology.

Now an assistant professor of genetics and computer science at Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA, Kundaje has received a 2016 NIH Director’s New Innovator Award to explore not just how the human genome sequence encodes function, but also why it functions in the way that it does. Kundaje even envisions a time when it might be possible to use sophisticated computational approaches to predict the genomic basis of many human diseases.

New Imaging Approach Reveals Lymph System in Brain

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Considering all the recent advances in mapping the complex circuitry of the human brain, you’d think we’d know all there is to know about the brain’s basic anatomy. That’s what makes the finding that I’m about to share with you so remarkable. Contrary to what I learned in medical school, the body’s lymphatic system extends to the brain—a discovery that could revolutionize our understanding of many brain disorders, from Alzheimer’s disease to multiple sclerosis (MS).

Researchers from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), the National Cancer Institute (NCI), and the University of Virginia, Charlottesville made this discovery by using a special MRI technique to scan the brains of healthy human volunteers [1]. As you see in this 3D video created from scans of a 47-year-old woman, the brain—just like the neck, chest, limbs, and other parts of the body—possesses a network of lymphatic vessels (green) that serves as a highway to circulate key immune cells and return metabolic waste products to the bloodstream.

Creative Minds: Mapping the Biocircuitry of Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

As a graduate student in the 1980s, Bruce Yankner wondered what if cancer-causing genes switched on in non-dividing neurons of the brain. Rather than form a tumor, would those genes cause neurons to degenerate? To explore such what-ifs, Yankner spent his days tinkering with neural cells, using viruses to insert various mutant genes and study their effects. In a stroke of luck, one of Yankner’s insertions encoded a precursor to a protein called amyloid. Those experiments and later ones from Yankner’s own lab showed definitively that high concentrations of amyloid, as found in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s disease, are toxic to neural cells [1].

The discovery set Yankner on a career path to study normal changes in the aging human brain and their connection to neurodegenerative diseases. At Harvard Medical School, Boston, Yankner and his colleague George Church are now recipients of an NIH Director’s 2016 Transformative Research Award to apply what they’ve learned about the aging brain to study changes in the brains of younger people with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, two poorly understood psychiatric disorders.

Creative Minds: A Transcriptional “Periodic Table” of Human Neurons

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: Mouse fibroblasts converted into induced neuronal cells, showing neuronal appendages (red), nuclei (blue) and the neural protein tau (yellow).

Credit: Kristin Baldwin, Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA

Writers have The Elements of Style, chemists have the periodic table, and biomedical researchers could soon have a comprehensive reference on how to make neurons in a dish. Kristin Baldwin of the Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA, has received a 2016 NIH Director’s Pioneer Award to begin drafting an online resource that will provide other researchers the information they need to reprogram mature human skin cells reproducibly into a variety of neurons that closely resemble those found in the brain and nervous system.

These lab-grown neurons could be used to improve our understanding of basic human biology and to develop better models for studying Alzheimer’s disease, autism, and a wide range of other neurological conditions. Such questions have been extremely difficult to explore in mice and other animal models because they have shorter lifespans and different brain structures than humans.

Previous Page Next Page