gut

Changes in Human Microbiome Precede Alzheimer’s Cognitive Declines

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

In people with Alzheimer’s disease, the underlying changes in the brain associated with dementia typically begin many years—or even decades—before a diagnosis. While pinpointing the exact causes of Alzheimer’s remains a major research challenge, they likely involve a combination of genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors. Now an NIH-funded study elucidates the role of another likely culprit that you may not have considered: the human gut microbiome, the trillions of diverse bacteria and other microbes that live primarily in our intestines [1].

Earlier studies had showed that the gut microbiomes of people with symptomatic Alzheimer’s disease differ from those of healthy people with normal cognition [2]. What this new work advances is that these differences arise early on in people who will develop Alzheimer’s, even before any obvious symptoms appear.

The science still has a ways to go before we’ll know if specific dietary changes can alter the gut microbiome and modify its influence on the brain in the right ways. But what’s exciting about this finding is it raises the possibility that doctors one day could test a patient’s stool sample to determine if what’s present from their gut microbiome correlates with greater early risk for Alzheimer’s dementia. Such a test would help doctors detect Alzheimer’s earlier and intervene sooner to slow or ideally even halt its advance.

The new findings, reported in the journal Science Translational Medicine, come from a research team led by Gautam Dantas and Beau Ances, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis. Ances is a clinician who treats and studies people with Alzheimer’s; Dantas is a basic researcher and expert on the gut microbiome.

The pair struck up a conversation one day about the possible connection between the gut microbiome and Alzheimer’s. While they knew about the earlier studies suggesting a link, they were surprised that nobody had looked at the gut microbiomes of people in the earliest, so-called preclinical, stages of the disease. That’s when dementia isn’t detectable, but the brain has formed amyloid-beta plaques, which are associated with Alzheimer’s.

To take a look, they enrolled 164 healthy volunteers, age 68 to 94, who performed normally on standard tests of cognition. They also collected stool samples from each volunteer and thoroughly analyzed them all the microbes from their gut microbiome. Study participants also kept food diaries and underwent extensive testing, including two types of brain scans, to look for signs of amyloid-beta plaques and tau protein accumulation that precede the onset of Alzheimer’s symptoms.

Among the volunteers, about a third (49 individuals) unfortunately had signs of early Alzheimer’s disease. And, as it turned out, their microbiomes showed differences, too.

The researchers found that those with preclinical Alzheimer’s disease had markedly different assemblages of gut bacteria. Their microbiomes differed in many of the bacterial species present. Those species-level differences also point to differences in the way their microbiomes would be expected to function at a metabolic level. These microbiome changes were observed even though the individuals didn’t seem to have any apparent differences in their diets.

The team also found that the microbiome changes correlated with amyloid-beta and tau levels in the brain. But they did not find any relationship to degenerative changes in the brain, which tend to happen later in people with Alzheimer’s.

The team is now conducting a five-year study that will follow volunteers to get a better handle on whether the differences observed in the gut microbiome are a cause or a consequence of the brain changes seen in Alzheimer’s. If it’s a cause, this discovery would raise the tantalizing possibility that specially formulated probiotics or fecal transplants that promote the growth of “good” bacteria over “bad” bacteria in the gut might slow the development of Alzheimer’s and its most devastating symptoms. It’s an exciting area of research and definitely one worth following in the years ahead.

References:

[1] Gut microbiome composition may be an indicator of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Ferreiro AL, Choi J, Ryou J, Newcomer EP, Thompson R, Bollinger RM, Hall-Moore C, Ndao IM, Sax L, Benzinger TLS, Stark SL, Holtzman DM, Fagan AM, Schindler SE, Cruchaga C, Butt OH, Morris JC, Tarr PI, Ances BM, Dantas G. Sci Transl Med. 2023 Jun 14;15(700):eabo2984. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abo2984. Epub 2023 Jun 14. PMID: 37315112.

[2] Gut microbiome alterations in Alzheimer’s disease. Vogt NM, Kerby RL, Dill-McFarland KA, Harding SJ, Merluzzi AP, Johnson SC, Carlsson CM, Asthana S, Zetterberg H, Blennow K, Bendlin BB, Rey FE. Sci Rep. 2017 Oct 19;7(1):13537. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-13601-y. PMID: 29051531; PMCID: PMC5648830.

Links:

Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias (National Institute on Aging/NIH)

Video: How Alzheimer’s Changes the Brain (NIA)

Dantas Lab (Washington University School of Medicine. St. Louis)

Ances Bioimaging Laboratory (Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis)

NIH Support: National Institute on Aging; National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

Could A Gut-Brain Connection Help Explain Autism?

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

You might think nutrient-sensing cells in the human gastrointestinal (GI) tract would have no connection whatsoever to autism spectrum disorder (ASD). But if Diego Bohórquez’s “big idea” is correct, these GI cells, called neuropods, could one day help to provide a direct link into understanding and treating some aspects of autism and other brain disorders.

Bohórquez, a researcher at Duke University, Durham, NC, recently discovered that cells in the intestine, previously known for their hormone-releasing ability, form extensions similar to neurons. He also found that those extensions connect to nerve fibers in the gut, which relay signals to the vagus nerve and onward to the brain. In fact, he found that those signals reach the brain in milliseconds [1].

Bohórquez has dedicated his lab to studying this direct, high-speed hookup between gut and brain and its impact on nutrient sensing, eating, and other essential behaviors. Now, with support from a 2019 NIH Director’s New Innovator Award, he will also explore the potential for treating autism and other brain disorders with drugs that act on the gut.

Bohórquez became interested in autism and its possible link to the gut-brain connection after a chance encounter with Geraldine Dawson, director of the Duke Center for Autism and Brain Development. Dawson mentioned that autism typically affects multiple organ systems.

With further reading, he discovered that kids with autism frequently cope with GI issues, including bowel inflammation, abdominal pain, constipation, and/or diarrhea [2]. They often also show unusual food-related behaviors, such as being extremely picky eaters. But his curiosity was especially piqued by evidence that certain gut microbes can influence abnormal behaviors in mice that model autism.

With his New Innovator Award, Bohórquez will study neuropods and the gut-brain connection in a mouse model of autism. Using the tools of optogenetics, which make it possible to activate cells with light, he’ll also see whether autism-like symptoms in mice can be altered or alleviated by controlling neuropods in the gut. Those symptoms include anxiety, repetitive behaviors, and lack of interest in interacting with other mice. He’ll also explore changes in the animals’ eating habits.

In another line of study, he will take advantage of intestinal tissue samples collected from people with autism. He’ll use those tissues to grow and then examine miniature intestinal “organoids,” looking for possible evidence that those from people with autism are different from others.

For the millions of people now living with autism, no truly effective drug therapies are available to help to manage the condition and its many behavioral and bodily symptoms. Bohórquez hopes one day to change that with drugs that act safely on the gut. In the meantime, he and his fellow “GASTRONAUTS” look forward to making some important and fascinating discoveries in the relatively uncharted territory where the gut meets the brain.

References:

[1] A gut-brain neural circuit for nutrient sensory transduction. Kaelberer MM, Buchanan KL, Klein ME, Barth BB, Montoya MM, Shen X, Bohórquez DV. Science. 2018 Sep 21;361(6408).

[2] Association of maternal report of infant and toddler gastrointestinal symptoms with autism: evidence from a prospective birth cohort. Bresnahan M, Hornig M, Schultz AF, Gunnes N, Hirtz D, Lie KK, Magnus P, Reichborn-Kjennerud T, Roth C, Schjølberg S, Stoltenberg C, Surén P, Susser E, Lipkin WI. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015 May;72(5):466-474.

Links:

Autism Spectrum Disorder (National Institute of Mental Health/NIH)

Bohórquez Lab (Duke University, Durham, NC)

Bohórquez Project Information (NIH RePORTER)

NIH Director’s New Innovator Award (Common Fund)

NIH Support: Common Fund; National Institute of Mental Health

Gut-Dwelling Bacterium Consumes Parkinson’s Drug

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Scientists continue to uncover the many fascinating ways in which the trillions of microbes that inhabit the human body influence our health. Now comes yet another surprising discovery: a medicine-eating bacterium residing in the human gut that may affect how well someone responds to the most commonly prescribed drug for Parkinson’s disease.

There have been previous hints that gut microbes might influence the effectiveness of levodopa (L-dopa), which helps to ease the stiffness, rigidity, and slowness of movement associated with Parkinson’s disease. Now, in findings published in Science, an NIH-funded team has identified a specific, gut-dwelling bacterium that consumes L-dopa [1]. The scientists have also identified the bacterial genes and enzymes involved in the process.

Parkinson’s disease is a progressive neurodegenerative condition in which the dopamine-producing cells in a portion of the brain called the substantia nigra begin to sicken and die. Because these cells and their dopamine are critical for controlling movement, their death leads to the familiar tremor, difficulty moving, and the characteristic slow gait. As the disease progresses, cognitive and behavioral problems can take hold, including depression, personality shifts, and sleep disturbances.

For the 10 million people in the world now living with this neurodegenerative disorder, and for those who’ve gone before them, L-dopa has been for the last 50 years the mainstay of treatment to help alleviate those motor symptoms. The drug is a precursor of dopamine, and, unlike dopamine, it has the advantage of crossing the blood-brain barrier. Once inside the brain, an enzyme called DOPA decarboxylase converts L-dopa to dopamine.

Unfortunately, only a small fraction of L-dopa ever reaches the brain, contributing to big differences in the drug’s efficacy from person to person. Since the 1970s, researchers have suspected that these differences could be traced, in part, to microbes in the gut breaking down L-dopa before it gets to the brain.

To take a closer look in the new study, Vayu Maini Rekdal and Emily Balskus, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, turned to data from the NIH-supported Human Microbiome Project (HMP). The project used DNA sequencing to identify and characterize the diverse collection of microbes that populate the healthy human body.

The researchers sifted through the HMP database for bacterial DNA sequences that appeared to encode an enzyme capable of converting L-dopa to dopamine. They found what they were looking for in a bacterial group known as Enterococcus, which often inhabits the human gastrointestinal tract.

Next, they tested the ability of seven representative Enterococcus strains to transform L-dopa. Only one fit the bill: a bacterium called Enterococcus faecalis, which commonly resides in a healthy gut microbiome. In their tests, this bacterium avidly consumed all the L-dopa, using its own version of a decarboxylase enzyme. When a specific gene in its genome was inactivated, E. faecalis stopped breaking down L-dopa.

These studies also revealed variability among human microbiome samples. In seven stool samples, the microbes tested didn’t consume L-dopa at all. But in 12 other samples, microbes consumed 25 to 98 percent of the L-dopa!

The researchers went on to find a strong association between the degree of L-dopa consumption and the abundance of E. faecalis in a particular microbiome sample. They also showed that adding E. faecalis to a sample that couldn’t consume L-dopa transformed it into one that could.

So how can this information be used to help people with Parkinson’s disease? Answers are already appearing. The researchers have found a small molecule that prevents the E. faecalis decarboxylase from modifying L-dopa—without harming the microbe and possibly destabilizing an otherwise healthy gut microbiome.

The finding suggests that the human gut microbiome might hold a key to predicting how well people with Parkinson’s disease will respond to L-dopa, and ultimately improving treatment outcomes. The finding also serves to remind us just how much the microbiome still has to tell us about human health and well-being.

Reference:

[1] Discovery and inhibition of an interspecies gut bacterial pathway for Levodopa metabolism. Maini Rekdal V, Bess EN, Bisanz JE, Turnbaugh PJ, Balskus EP. Science. 2019 Jun 14;364(6445).

Links:

Parkinson’s Disease Information Page (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke/NIH)

Balskus Lab (Harvard University, Cambridge, MA)

NIH Support: National Institute of General Medical Sciences; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

Creative Minds: The Human Gut Microbiome’s Top 100 Hits

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Michael Fishbach

Microbes that live in dirt often engage in their own deadly turf wars, producing a toxic mix of chemical compounds (also called “small molecules”) that can be a source of new antibiotics. When he started out in science more than a decade ago, Michael Fischbach studied these soil-dwelling microbes to look for genes involved in making these compounds.

Eventually, Fischbach, who is now at the University of California, San Francisco, came to a career-altering realization: maybe he didn’t need to dig in dirt! He hypothesized an even better way to improve human health might be found in the genes of the trillions of microorganisms that dwell in and on our bodies, known collectively as the human microbiome.

Mouse Study Finds Microbe Might Protect against Food Poisoning

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

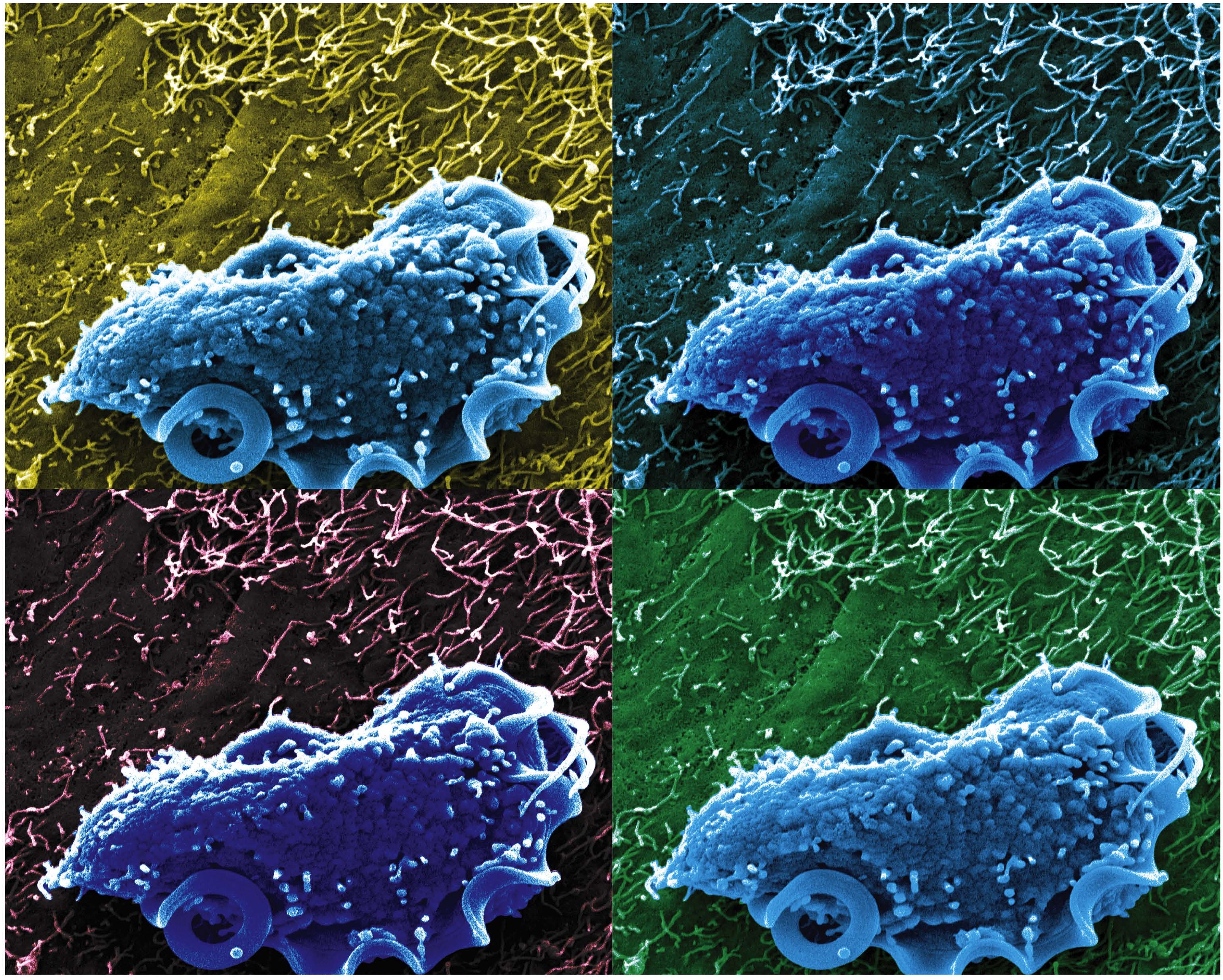

Caption: Scanning electron microscopy image of T. mu in the mouse colon.

Credit: Aleksey Chudnovskiy and Miriam Merad, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai

Recently, we humans have started to pay a lot more attention to the legions of bacteria that live on and in our bodies because of research that’s shown us the many important roles they play in everything from how we efficiently metabolize food to how well we fend off disease. And, as it turns out, bacteria may not be the only interior bugs with the power to influence our biology positively—a new study suggests that an entirely different kingdom of primarily single-celled microbes, called protists, may be in on the act.

In a study published in the journal Cell, an NIH-funded research team reports that it has identified a new protozoan, called Tritrichomonas musculis (T. mu), living inside the gut of laboratory mice. That sounds bad—but actually this little wriggler was potentially providing a positive benefit to the mice. Not only did T. mu appear to boost the animals’ immune systems, it spared them from the severe intestinal infection that typically occurs after eating food contaminated with toxic Salmonella bacteria. While it’s not yet clear if protists exist that can produce similar beneficial effects in humans, there is evidence that a close relative of T. mu frequently resides in the intestines of people around the world.

Creative Minds: New Piece in the Crohn’s Disease Puzzle?

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Gwendalyn Randolph

Back in the early 1930s, Burrill Crohn, a gastroenterologist in New York, decided to examine intestinal tissue biopsies from some of his patients who were suffering from severe bowel problems. It turns out that 14 showed signs of severe inflammation and structural damage in the lower part of the small intestine. As Crohn later wrote a medical colleague, “I have discovered, I believe, a new intestinal disease …” [1]

More than eight decades later, the precise cause of this disorder, which is now called Crohn’s disease, remains a mystery. Researchers have uncovered numerous genes, microbes, immunologic abnormalities, and other factors that likely contribute to the condition, estimated to affect hundreds of thousands of Americans and many more worldwide [2]. But none of these discoveries alone appears sufficient to trigger the uncontrolled inflammation and pathology of Crohn’s disease.

Other critical pieces of the Crohn’s puzzle remain to be found, and Gwendalyn Randolph thinks she might have her eyes on one of them. Randolph, an immunologist at Washington University, St. Louis, suspects that Crohn’s disease and other related conditions, collectively called inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), stems from changes in vessels that carry nutrients, immune cells, and possibly microbial components away from the intestinal wall. To pursue this promising lead, Rudolph has received a 2015 NIH Director’s Pioneer Award.

Manipulating Microbes: New Toolbox for Better Health?

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron (white) living on mammalian cells in the gut (large pink cells coated in microvilli) and being activated by exogenously added compounds (small green dots) to express specific genes, such as those encoding light-generating luciferase proteins (glowing bacteria).

Credit: Janet Iwasa, Broad Visualization Group, MIT Media Lab

When you think about the cells that make up your body, you probably think about the cells in your skin, blood, heart, and other tissues and organs. But the one-celled microbes that live in and on the human body actually outnumber your own cells by a factor of about 10 to 1. Such microbes are especially abundant in the human gut, where some of them play essential roles in digestion, metabolism, immunity, and maybe even your mood and mental health. You are not just an organism. You are a superorganism!

Now imagine for a moment if the microbes that live inside our guts could be engineered to keep tabs on our health, sounding the alarm if something goes wrong and perhaps even acting to fix the problem. Though that may sound like science fiction, an NIH-funded team from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge, MA, is already working to realize this goal. Most recently, they’ve developed a toolbox of genetic parts that make it possible to program precisely one of the most common bacteria found in the human gut—an achievement that provides a foundation for engineering our collection of microbes, or microbiome, in ways that may treat or prevent disease.

Who Knew? Gut Bacteria Contribute to Malnutrition

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

A child suffering from kwashiorkor.

Source: CDC/Phil

Here’s a surprising result from a new NIH-funded study: a poor diet isn’t the only cause of severe malnutrition. It seems that a ‘bad’ assortment of microbes in the intestine can conspire with a nutrient poor diet to promote and perpetuate malnutrition [1].

Most of us don’t spend time thinking about it, but healthy humans harbor about 100 trillion bacteria in our intestines and trillions more in our nose, mouth, skin, and urogenital tracts. And though your initial reaction might be “yuck,” the presence of these microbes is generally a good thing. We’ve evolved with this bacterial community because they provide services—from food digestion to bolstering the immune response—and we give them food and shelter. We call these bacterial sidekicks our ‘microbiome,’ and the latest research, much of it NIH-funded, reveals that these life passengers are critical for good health. You read that right—we need bacteria. The trouble starts when the wrong ones take up residence in our body, or the bacterial demographics shift. Then diseases from eczema and obesity to asthma and heart disease may result. Indeed, we’ve learned that microbes even modulate our sex hormones and influence the risk of autoimmune diseases like type 1 diabetes. [2]