oral health

Microbe Normally Found in the Mouth May Drive Progression of Colorectal Cancer

Posted on by Dr. Monica M. Bertagnolli

Colorectal cancer is a leading cause of death from cancer in the United States. We know that risk of colorectal cancer goes up with age, certain coexisting health conditions, family history, smoking, alcohol use, and other factors. Researchers are also trying to learn more about what leads colorectal cancer to grow and spread. Now, findings from a new study supported in part by NIH add to evidence that colorectal tumor growth may be driven by a surprising bad actor: a microbe that’s normally found in the mouth.1

The findings, reported in Nature, suggest that a subtype of the bacterium Fusobacterium nucleatum has distinct genetic properties that may allow it to withstand acidic conditions in the stomach, infect colorectal tumors, and potentially drive their growth, which may lead to poorer patient outcomes. The discoveries suggest that the microbe could eventually be used as a target for detecting and treating colorectal cancer.

The study was conducted by a team led by Susan Bullman and Christopher D. Johnston at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center in Seattle. In 2022, the team published findings from a pair of studies implicating Fusobacterium nucleatum in the progression and spread of colorectal cancer.2,3 Their findings weren’t the first to suggest a link between the microbe and colorectal cancer. But their work offered important evidence that the microbe might alter colorectal tumors in ways that made them more likely to grow and spread. They also found that the microbe may affect the way colorectal cancer responds to or resists chemotherapy treatment.

Follow-up studies suggested there might be more to the story, pointing to the possibility that certain strains of the bacterium might differ from others in important ways. The findings suggested that there may be a more specific subtype, not yet defined, that was responsible for driving colorectal cancer growth.

To look deeper into this in the new study, Bullman and Johnston, with first author Martha Zepeda Rivera, analyzed a collection of 55 strains of the microbe taken from human colorectal cancer samples. They also compared these at the genetic level to another 80 strains of the microbe taken from the mouths of people who didn’t have cancer.

Their studies uncovered 483 genetic factors that turned up more often in Fusobacterium nucleatum from colorectal tumors. Those strains mainly belonged to a subspecies called Fusobacterium nucleatum animalis (Fna). More detailed study led to another surprise. The Fna included two genetically distinct groups or “clades” that had never been described, which the researchers called Fna C1 and C2. It turned out that only Fna C2 occurs at high levels in colorectal tumors.

The researchers found that this specific subtype within colorectal tumors carries 195 genetic factors that may allow it to grow more rapidly, withstand the acidic environment in the stomach, and take up residence in the gastrointestinal tract, where it can drive colorectal cancer growth. When the researchers infected a mouse model of colitis, a condition involving inflamed intestines that is a risk factor for colorectal cancer, they found that Fna C2 caused the development of more tumors compared to those infected with Fna C1.

Studies of tumors from 116 patients with colorectal cancer also showed more Fna C2. It was elevated in about 50% of cases. In fact, only this strain turned up more often in cancer compared to healthy tissue nearby. Stool samples of 627 people with colorectal cancer and 619 healthy people also showed more of this specific microbial strain in association with cancer.

This discovery is important because it suggests it’s only the Fna C2 subtype that’s associated with driving colorectal tumor growth, meaning it could help in the development of new methods for colorectal cancer screening and treatment. The researchers suggest it may one day even be possible to develop microbial-based therapies using modified versions of the bacterial strain to deliver treatments straight into tumors.

In addition, while the microbe is normally found in healthy mouths, it’s also enriched in periodontal (gum) disease, dental infections, and oral cancers.4 It will be interesting to learn more in future studies about the connections between various Fusobacterium nucleatum subtypes, oral health, and other health conditions throughout the body, including colorectal cancer.

References:

[1] Zepeda-Rivera M, et al. A distinct Fusobacterium nucleatum clade dominates the colorectal cancer niche. Nature. DOI: 10.1038/s41586-024-07182-w (2024).

[2] LaCourse KD, et al. The cancer chemotherapeutic 5-fluorouracil is a potent Fusobacterium nucleatum inhibitor and its activity is modified by intratumoral microbiota. Cell Rep. DOI: 10.1016/j.celrep.2022.111625 (2022).

[3] Galeano Niño JL, et al. Effect of the intratumoral microbiota on spatial and cellular heterogeneity in cancer. Nature. DOI: 10.1038/s41586-022-05435-0 (2022).

[4] Chen Y, et al. More Than Just a Periodontal Pathogen –the Research Progress on Fusobacterium nucleatum. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. DOI: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.815318 (2022).

NIH Support: National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Cancer Institute

Connecting the Dots: Oral Infection to Rheumatoid Arthritis

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

To keep your teeth and gums healthy for a lifetime, it’s important to brush and floss each day and see your dentist regularly. But what you might not often stop to consider is how essential good oral health really is to your overall well-being. The mouth, after all, is connected to the rest of the body, and oral infections can contribute to problems elsewhere.

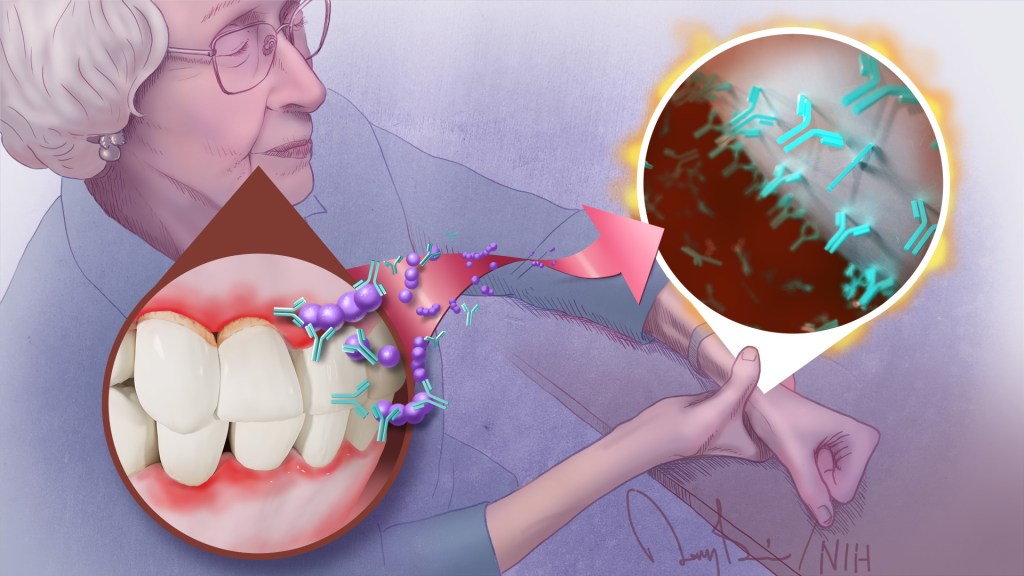

A good case in point comes from a study just published in the journal Science Translational Medicine. The study, though small, offers some of the most convincing evidence yet for a direct link between gum, or periodontal, disease and the rheumatoid arthritis that flares most commonly in the hands, wrists, and knees [1]. If confirmed in larger follow-up studies, the finding suggests that one way for people with both diseases to contend with painful arthritic flare-ups will be to prevent them by practicing good oral hygiene and controlling their periodontal disease.

For many years, there had been suggestions that the oral bacteria causing periodontal disease might contribute to rheumatoid arthritis. For instance, past studies have found that periodontal disease occurs even more often in people with rheumatoid arthritis. People with both conditions also tend to have more severe arthritic symptoms that can be more stubbornly resistant to treatment.

What’s been missing is the precise underlying mechanisms to confirm the connection. To help connect the dots, a research team, which included Dana Orange, Rockefeller University, New York, NY, and William Robinson, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, decided to look closer.

They looked first in the blood, not directly at an arthritic joint or an inflamed periodontium, the tissues that hold a tooth in place. They were interested in whether telltale changes in the blood of people with rheumatoid arthritis correlated with the start of another painful flare-up in one or more of their joints.

One of those possible changes involves proteins that carry a particular chemical modification that places the amino acid citrulline on their surface. These citrulline-marked proteins are found in many parts of the human body, including the joints. Intriguingly, they also are present on bacteria, including those in the mouth.

Because of this bacterial connection, the researchers looked in the blood for a specific set of antibodies known as ACPAs, short for anti-citrullinated protein antibodies. They recognize citrullinated proteins that are foreign to the body and mark them for attack.

But the attack isn’t always perfectly aimed, and studies have shown the presence of ACPAs in the joints of people with rheumatoid arthritis is associated with increasing disease activity and more frequent arthritis flares. Periodontal disease, too, is especially common in people with rheumatoid arthritis who have abnormally high levels of circulating ACPAs.

In the new study, the researchers followed five women with rheumatoid arthritis for one to four years. Two of them had severe periodontal disease while the other three had no periodontal disease.

Each week, the study volunteers provided a small blood sample for researchers to study changes at the level of RNA, the genetic material that encodes proteins. They also studied changes in certain immune cells, along with any changes in their medication, dental care, or arthritis symptoms. For additional information, they also looked at blood and joint fluid samples from 67 other people with and without arthritis, including individuals with healthy gums or mild, moderate, or severe periodontal disease.

Overall, the evidence shows that people with more severe periodontal disease experienced repeated influxes of oral bacteria into their blood even when they hadn’t had a recent dental procedure. These findings suggested that when their inflamed gums became more damaged and “leaky,” bacteria in the mouth could spill into the bloodstream.

The researchers also found that those oral invaders carried many citrullinated proteins. Once they got into the bloodstream, inflammatory immune cells detected them and released ACPAs.

The researchers showed in the lab that those antibodies bind the same oral bacteria detected in the blood of people with periodontal disease and rheumatoid arthritis. In fact, those with both conditions had a wide variety of genetically distinct ACPAs, as would be expected if their immune systems were challenged repeatedly over time with oral bacteria.

The overarching idea is that these antibodies prime the immune system to attack oral bacteria. But after it gets started, the attack mistakenly expands and targets citrullinated proteins in the joints. That triggers a flare-up in a joint and the characteristic inflammation, stiffness, and joint damage.

While more study is needed to fill in the molecular details, this discovery raises an encouraging possibility. Taking care of your teeth and periodontal disease isn’t just a wise idea to maintain good oral health over a lifetime. For some of the approximately 1 million Americans with rheumatoid arthritis, it may help to manage and perhaps even prevent a painful flare-up in one or more of their affected joints.

Reference:

[1] Oral mucosal breaks trigger anti-citrullinated bacterial and human protein antibody responses in rheumatoid arthritis. Brewer RC, Lanz TV, Hale CR, Sepich-Poore GD, Martino C, Swafford AD, Carroll TS, Kongpachith S, Blum LK, Elliott SE, Blachere NE, Parveen S, Fak J, Yao V, Troyanskaya O, Frank MO, Bloom MS, Jahanbani S, Gomez AM, Iyer R, Ramadoss NS, Sharpe O, Chandrasekaran S, Kelmenson LB, Wang Q, Wong H, Torres HL, Wiesen M, Graves DT, Deane KD, Holers VM, Knight R, Darnell RB, Robinson WH, Orange DE. Sci Transl Med. 2023 Feb 22;15(684):eabq8476.

Links:

Rheumatoid Arthritis (National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases)

Periodontal (Gum) Disease (National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research/NIH)

Oral Hygiene (NIDCR)

Dana Orange (Rockefeller University, New York NY)

Robinson Lab (Stanford University, Stanford, CA)

NIH Support: National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; National Human Genome Research Institute; National Institute of General Medical Sciences; National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences; National Cancer Institute

Using Science To Solve Oral Health Inequities

Posted on by Rena D'Souza, D.D.S., M.S., Ph.D., National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research

At NIH, we have a front row seat to remarkable advances in science and technology that help Americans live longer, healthier lives. By studying the role that the mouth and saliva can play in the transmission and prevention of disease, the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) contributed to our understanding of infectious agents like the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, the cause of COVID-19. While these and other NIH-supported advances undoubtedly can improve our nation’s health as a whole, not everyone enjoys the benefits equally—or at all. As a result, people’s health, including their oral health, suffers.

That’s a major takeaway from Oral Health in America: Advances and Challenges, a report that NIDCR recently released on the status of the nation’s oral health over the last 20 years. The report shows that oral health has improved in some ways, but people from marginalized groups —such as those experiencing poverty, people from racial and ethnic minority groups, the frail elderly, and immigrants—shoulder an unequal burden of oral disease.

At NIDCR, we are taking the lessons learned from the Oral Health in America report and using them to inform our research. It will help us to discover ways to eliminate these oral health differences, or disparities, so that everyone can enjoy the benefits of good oral health.

Why does oral health matter? It is essential for our overall health, well-being, and productivity. Untreated oral diseases, such as tooth decay and gum disease, can cause infections, pain, and tooth loss, which affect the ability to chew, swallow, eat a balanced diet, speak, smile, and go to school and work.

Treatments to fix these problems are expensive, so people of low socioeconomic means are less likely to receive quality care in a timely manner. Importantly, untreated gum disease is associated with serous systemic conditions such as diabetes, heart disease, and Alzheimer’s disease.

A person experiencing poverty also may be at increased risk for mental illness. That, in turn, can make it hard to practice oral hygiene, such as toothbrushing and flossing, or to maintain a relationship with a dental provider. Mental illnesses and substance use disorders often go hand-in-hand, and overuse of opioids, alcohol, and tobacco products also can raise the risk for tooth decay, gum disease, and oral cancers. Untreated dental diseases in this setting can cause pain, sometimes leading to increased substance use as a means of self-medication.

Research to understand better the connections between mental health, addiction, and oral health, particularly as they relate to health disparities, can help us develop more effective ways to treat patients. It also will help us prepare health providers, including dentists, to deliver the right kind of care to patients.

Another area that is ripe for investigation is to find ways to make it easier for people to get dental care, especially those from marginalized or rural communities. For example, the COVID-19 pandemic spurred more dentists to use teledentistry, where practitioners meet with patients remotely as a way to provide certain aspects of care, such as consultations, oral health screenings, treatment planning, and education.

Teledentistry holds promise as a cost-saving approach to connect dentists to people living in regions that may have a shortage of dentists. Some evidence suggests that providing access to oral health care outside of dental clinics—such as in schools, primary care offices, and community centers—has helped reduce oral health disparities in children. We need additional research to find out if this type of approach also might reduce disparities in adults.

These are just some of the opportunities highlighted in the Oral Health in America report that will inform NIDCR’s research in the coming years. Just as science, innovation, and new technologies have helped solve some of the most challenging health problems of our time, so too can they lead us to solutions for tackling oral health disparities. Our job will not be done until we can improve oral and overall health for everyone across America.

Links:

Oral Health in America: Advances and Challenges (National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research/NIH)

Oral Health in America Editors Issue Guidance for Improving Oral Health for All (NIDCR)

NIH, HHS Leaders Call for Research and Policy Changes To Address Oral Health Inequities (NIDCR)

NIH/NIDCR Releases Oral Health in America: Advances and Challenges (NIDCR)

Note: Acting NIH Director Lawrence Tabak has asked the heads of NIH’s Institutes and Centers (ICs) to contribute occasional guest posts to the blog to highlight some of the interesting science that they support and conduct. This is the 11th in the series of NIH IC guest posts that will run until a new permanent NIH director is in place.

Study Demonstrates Saliva Can Spread Novel Coronavirus

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

COVID-19 is primarily considered a respiratory illness that affects the lungs, upper airways, and nasal cavity. But COVID-19 can also affect other parts of the body, including the digestive system, blood vessels, and kidneys. Now, a new study has added something else: the mouth.

The study, published in the journal Nature Medicine, shows that SARS-CoV-2, which is the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, can actively infect cells that line the mouth and salivary glands. The new findings may help explain why COVID-19 can be detected by saliva tests, and why about half of COVID-19 cases include oral symptoms, such as loss of taste, dry mouth, and oral ulcers. These results also suggest that the mouth and its saliva may play an important—and underappreciated—role in spreading SARS-CoV-2 throughout the body and, perhaps, transmitting it from person to person.

The latest work comes from Blake Warner of NIH’s National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research; Kevin Byrd, Adams School of Dentistry at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill; and their international colleagues. The researchers were curious about whether the mouth played a role in transmitting SARS-CoV-2. They were already aware that transmission is more likely when people speak, cough, and even sing. They also knew from diagnostic testing that the saliva of people with COVID-19 can contain high levels of SARS-CoV-2. But did that virus in the mouth and saliva come from elsewhere? Or, was SARS-CoV-2 infecting and replicating in cells within the mouth as well?

To find out, the research team surveyed oral tissue from healthy people in search of cells that express the ACE2 receptor protein and the TMPRSS2 enzyme protein, both of which SARS-CoV-2 depends upon to enter and infect human cells. They found the proteins may be expressed individually in the primary cells of all types of salivary glands and in tissues lining the oral cavity. Indeed, a small portion of salivary gland and gingival (gum) cells around our teeth, simultaneously expressed the genes encoding ACE2 and TMPRSS2.

Next, the team detected signs of SARS-CoV-2 in just over half of the salivary gland tissue samples that it examined from people with COVID-19. The samples included salivary gland tissue from one person who had died from COVID-19 and another with acute illness.

The researchers also found evidence that the coronavirus was actively replicating to make more copies of itself. In people with mild or asymptomatic COVID-19, oral cells that shed into the saliva bathing the mouth were found to contain RNA for SARS-CoV-2, as well its proteins that it uses to enter human cells.

The researchers then collected saliva from another group of 35 volunteers, including 27 with mild COVID-19 symptoms and another eight who were asymptomatic. Of the 27 people with symptoms, those with virus in their saliva were more likely to report loss of taste and smell, suggesting that oral infection might contribute to those symptoms of COVID-19, though the primary cause may be infection of the olfactory tissues in the nose.

Another important question is whether SARS-CoV-2, while suspended in saliva, can infect other healthy cells. To get the answer, the researchers exposed saliva from eight people with asymptomatic COVID-19 to healthy cells grown in a lab dish. Saliva from two of the infected volunteers led to infection of the healthy cells. These findings raise the unfortunate possibility that even people with asymptomatic COVID-19 might unknowingly transmit SARS-CoV-2 to other people through their saliva.

Overall, the findings suggest that the mouth plays a greater role in COVID-19 infection and transmission than previously thought. The researchers suggest that virus-laden saliva, when swallowed or inhaled, may spread virus into the throat, lungs, or digestive system. Knowing this raises the hope that a better understanding of how SARS-CoV-2 infects the mouth could help in pointing to new ways to prevent the spread of this devastating virus.

Reference:

[1] SARS-CoV-2 infection of the oral cavity and saliva. Huang N, Pérez P, Kato T, Mikami Y, Chiorini JA, Kleiner DE, Pittaluga S, Hewitt SM, Burbelo PD, Chertow D; NIH COVID-19 Autopsy Consortium; HCA Oral and Craniofacial Biological Network, Frank K, Lee J, Boucher RC, Teichmann SA, Warner BM, Byrd KM, et. al Nat Med. 2021 Mar 25.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Saliva & Salivary Gland Disorders (National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research/NIH)

Blake Warner (National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research/NIH)

Kevin Byrd (Adams School of Dentistry at University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill)

NIH Support: National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research; National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences

The Science of Saliva

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

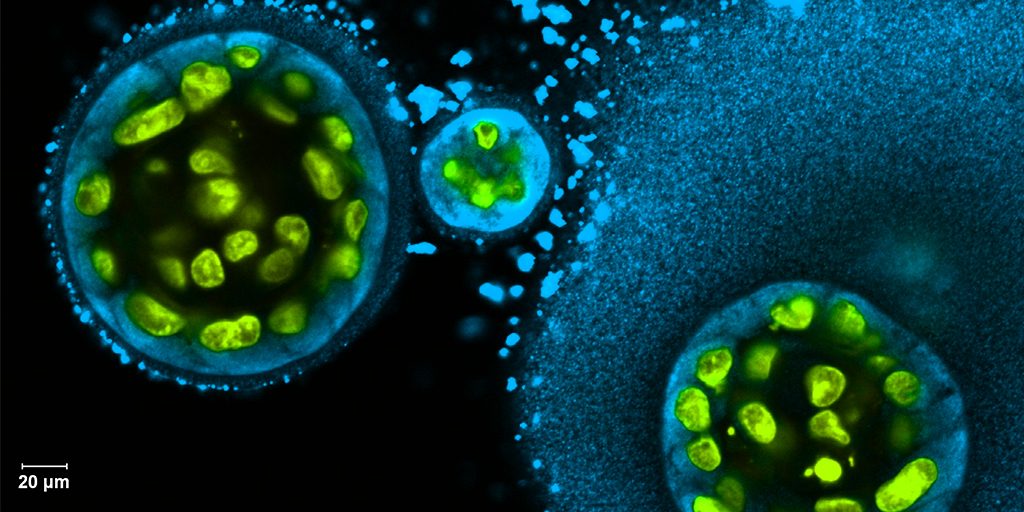

Credit: Swati Pradhan-Bhatt, Christiana Care Health System, Newark, DE

Whether it’s salmon sizzling on the grill or pizza fresh from the oven, you probably have a favorite food that makes your mouth water. But what if your mouth couldn’t water—couldn’t make enough saliva? When salivary glands stop working and the mouth becomes dry, either from disease or as a side effect of medical treatment, the once-routine act of eating can become a major challenge.

To help such people, researchers are now trying to engineer replacement salivary glands. While the research is still in the early stages, this image captures a crucial first step in the process: generating 3D structures of saliva-secreting cells (yellow). When grown on a scaffold of biocompatible polymers infused with factors to encourage development, these cells cluster into spherical structures similar to those seen in salivary glands. And they don’t just look like salivary cells, they act like them, producing the distinctive enzyme in saliva, alpha amylase (blue).

Snapshots of Life: Stronger Than It Looks

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: Olivier Duverger and Maria I. Morasso, National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, NIH

If you went out and asked folks what they’re seeing in this picture, most would probably guess an elegantly woven basket, or a soft, downy feather. But what this scanning electron micrograph actually shows isn’t at all soft: it is the hardest substance in the mammalian body—tooth enamel!

This exquisitely detailed image—a winner of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology’s 2015 BioArt competition—was generated by Olivier Duverger and Maria Morasso of NIH’s National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Before placing a sample of mouse dental enamel under the microscope, they treated it briefly with acid in order to reveal how the tissue’s mineralized rods are interwoven in a manner that gives teeth both strength and flexibility.