periodontal disease

Connecting the Dots: Oral Infection to Rheumatoid Arthritis

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

To keep your teeth and gums healthy for a lifetime, it’s important to brush and floss each day and see your dentist regularly. But what you might not often stop to consider is how essential good oral health really is to your overall well-being. The mouth, after all, is connected to the rest of the body, and oral infections can contribute to problems elsewhere.

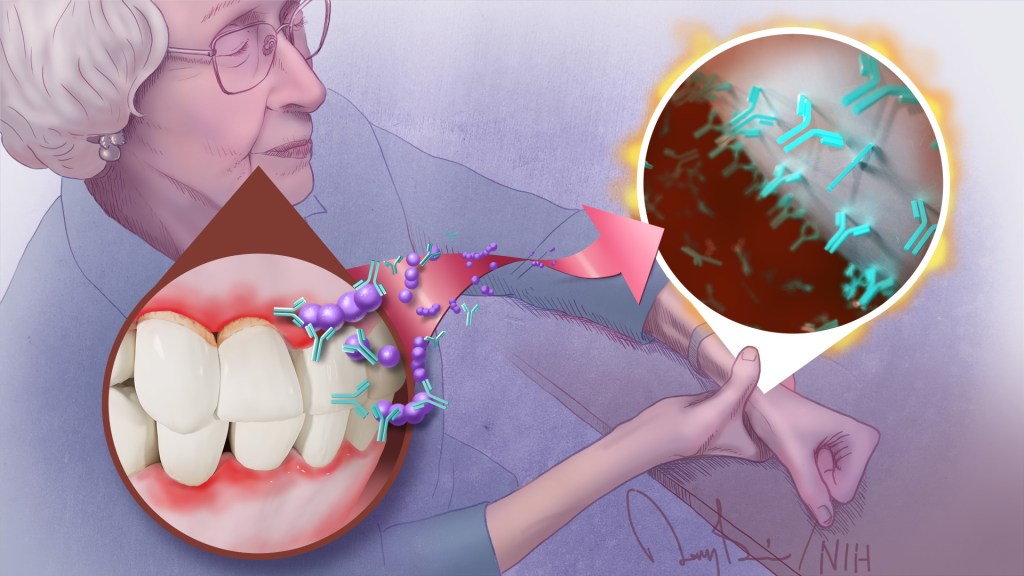

A good case in point comes from a study just published in the journal Science Translational Medicine. The study, though small, offers some of the most convincing evidence yet for a direct link between gum, or periodontal, disease and the rheumatoid arthritis that flares most commonly in the hands, wrists, and knees [1]. If confirmed in larger follow-up studies, the finding suggests that one way for people with both diseases to contend with painful arthritic flare-ups will be to prevent them by practicing good oral hygiene and controlling their periodontal disease.

For many years, there had been suggestions that the oral bacteria causing periodontal disease might contribute to rheumatoid arthritis. For instance, past studies have found that periodontal disease occurs even more often in people with rheumatoid arthritis. People with both conditions also tend to have more severe arthritic symptoms that can be more stubbornly resistant to treatment.

What’s been missing is the precise underlying mechanisms to confirm the connection. To help connect the dots, a research team, which included Dana Orange, Rockefeller University, New York, NY, and William Robinson, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, decided to look closer.

They looked first in the blood, not directly at an arthritic joint or an inflamed periodontium, the tissues that hold a tooth in place. They were interested in whether telltale changes in the blood of people with rheumatoid arthritis correlated with the start of another painful flare-up in one or more of their joints.

One of those possible changes involves proteins that carry a particular chemical modification that places the amino acid citrulline on their surface. These citrulline-marked proteins are found in many parts of the human body, including the joints. Intriguingly, they also are present on bacteria, including those in the mouth.

Because of this bacterial connection, the researchers looked in the blood for a specific set of antibodies known as ACPAs, short for anti-citrullinated protein antibodies. They recognize citrullinated proteins that are foreign to the body and mark them for attack.

But the attack isn’t always perfectly aimed, and studies have shown the presence of ACPAs in the joints of people with rheumatoid arthritis is associated with increasing disease activity and more frequent arthritis flares. Periodontal disease, too, is especially common in people with rheumatoid arthritis who have abnormally high levels of circulating ACPAs.

In the new study, the researchers followed five women with rheumatoid arthritis for one to four years. Two of them had severe periodontal disease while the other three had no periodontal disease.

Each week, the study volunteers provided a small blood sample for researchers to study changes at the level of RNA, the genetic material that encodes proteins. They also studied changes in certain immune cells, along with any changes in their medication, dental care, or arthritis symptoms. For additional information, they also looked at blood and joint fluid samples from 67 other people with and without arthritis, including individuals with healthy gums or mild, moderate, or severe periodontal disease.

Overall, the evidence shows that people with more severe periodontal disease experienced repeated influxes of oral bacteria into their blood even when they hadn’t had a recent dental procedure. These findings suggested that when their inflamed gums became more damaged and “leaky,” bacteria in the mouth could spill into the bloodstream.

The researchers also found that those oral invaders carried many citrullinated proteins. Once they got into the bloodstream, inflammatory immune cells detected them and released ACPAs.

The researchers showed in the lab that those antibodies bind the same oral bacteria detected in the blood of people with periodontal disease and rheumatoid arthritis. In fact, those with both conditions had a wide variety of genetically distinct ACPAs, as would be expected if their immune systems were challenged repeatedly over time with oral bacteria.

The overarching idea is that these antibodies prime the immune system to attack oral bacteria. But after it gets started, the attack mistakenly expands and targets citrullinated proteins in the joints. That triggers a flare-up in a joint and the characteristic inflammation, stiffness, and joint damage.

While more study is needed to fill in the molecular details, this discovery raises an encouraging possibility. Taking care of your teeth and periodontal disease isn’t just a wise idea to maintain good oral health over a lifetime. For some of the approximately 1 million Americans with rheumatoid arthritis, it may help to manage and perhaps even prevent a painful flare-up in one or more of their affected joints.

Reference:

[1] Oral mucosal breaks trigger anti-citrullinated bacterial and human protein antibody responses in rheumatoid arthritis. Brewer RC, Lanz TV, Hale CR, Sepich-Poore GD, Martino C, Swafford AD, Carroll TS, Kongpachith S, Blum LK, Elliott SE, Blachere NE, Parveen S, Fak J, Yao V, Troyanskaya O, Frank MO, Bloom MS, Jahanbani S, Gomez AM, Iyer R, Ramadoss NS, Sharpe O, Chandrasekaran S, Kelmenson LB, Wang Q, Wong H, Torres HL, Wiesen M, Graves DT, Deane KD, Holers VM, Knight R, Darnell RB, Robinson WH, Orange DE. Sci Transl Med. 2023 Feb 22;15(684):eabq8476.

Links:

Rheumatoid Arthritis (National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases)

Periodontal (Gum) Disease (National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research/NIH)

Oral Hygiene (NIDCR)

Dana Orange (Rockefeller University, New York NY)

Robinson Lab (Stanford University, Stanford, CA)

NIH Support: National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; National Human Genome Research Institute; National Institute of General Medical Sciences; National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences; National Cancer Institute

Using Science To Solve Oral Health Inequities

Posted on by Rena D'Souza, D.D.S., M.S., Ph.D., National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research

At NIH, we have a front row seat to remarkable advances in science and technology that help Americans live longer, healthier lives. By studying the role that the mouth and saliva can play in the transmission and prevention of disease, the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) contributed to our understanding of infectious agents like the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, the cause of COVID-19. While these and other NIH-supported advances undoubtedly can improve our nation’s health as a whole, not everyone enjoys the benefits equally—or at all. As a result, people’s health, including their oral health, suffers.

That’s a major takeaway from Oral Health in America: Advances and Challenges, a report that NIDCR recently released on the status of the nation’s oral health over the last 20 years. The report shows that oral health has improved in some ways, but people from marginalized groups —such as those experiencing poverty, people from racial and ethnic minority groups, the frail elderly, and immigrants—shoulder an unequal burden of oral disease.

At NIDCR, we are taking the lessons learned from the Oral Health in America report and using them to inform our research. It will help us to discover ways to eliminate these oral health differences, or disparities, so that everyone can enjoy the benefits of good oral health.

Why does oral health matter? It is essential for our overall health, well-being, and productivity. Untreated oral diseases, such as tooth decay and gum disease, can cause infections, pain, and tooth loss, which affect the ability to chew, swallow, eat a balanced diet, speak, smile, and go to school and work.

Treatments to fix these problems are expensive, so people of low socioeconomic means are less likely to receive quality care in a timely manner. Importantly, untreated gum disease is associated with serous systemic conditions such as diabetes, heart disease, and Alzheimer’s disease.

A person experiencing poverty also may be at increased risk for mental illness. That, in turn, can make it hard to practice oral hygiene, such as toothbrushing and flossing, or to maintain a relationship with a dental provider. Mental illnesses and substance use disorders often go hand-in-hand, and overuse of opioids, alcohol, and tobacco products also can raise the risk for tooth decay, gum disease, and oral cancers. Untreated dental diseases in this setting can cause pain, sometimes leading to increased substance use as a means of self-medication.

Research to understand better the connections between mental health, addiction, and oral health, particularly as they relate to health disparities, can help us develop more effective ways to treat patients. It also will help us prepare health providers, including dentists, to deliver the right kind of care to patients.

Another area that is ripe for investigation is to find ways to make it easier for people to get dental care, especially those from marginalized or rural communities. For example, the COVID-19 pandemic spurred more dentists to use teledentistry, where practitioners meet with patients remotely as a way to provide certain aspects of care, such as consultations, oral health screenings, treatment planning, and education.

Teledentistry holds promise as a cost-saving approach to connect dentists to people living in regions that may have a shortage of dentists. Some evidence suggests that providing access to oral health care outside of dental clinics—such as in schools, primary care offices, and community centers—has helped reduce oral health disparities in children. We need additional research to find out if this type of approach also might reduce disparities in adults.

These are just some of the opportunities highlighted in the Oral Health in America report that will inform NIDCR’s research in the coming years. Just as science, innovation, and new technologies have helped solve some of the most challenging health problems of our time, so too can they lead us to solutions for tackling oral health disparities. Our job will not be done until we can improve oral and overall health for everyone across America.

Links:

Oral Health in America: Advances and Challenges (National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research/NIH)

Oral Health in America Editors Issue Guidance for Improving Oral Health for All (NIDCR)

NIH, HHS Leaders Call for Research and Policy Changes To Address Oral Health Inequities (NIDCR)

NIH/NIDCR Releases Oral Health in America: Advances and Challenges (NIDCR)

Note: Acting NIH Director Lawrence Tabak has asked the heads of NIH’s Institutes and Centers (ICs) to contribute occasional guest posts to the blog to highlight some of the interesting science that they support and conduct. This is the 11th in the series of NIH IC guest posts that will run until a new permanent NIH director is in place.

Nanodiamonds Shine in Root Canal Study

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

When the time comes to get relief from a dental problem, we are all glad that dentistry has come so far—much of the progress based on research supported by NIH’s National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. Still, almost no one looks forward to getting a root canal. Not only can the dental procedure be uncomfortable and costly, there’s also a risk of failure due to infection or other complications. But some NIH-supported researchers have now come up with what may prove to be a dazzling strategy for reducing that risk: nanodiamonds!

That’s right, these researchers decided to add tiny diamonds—so small that millions could fit on the head of the pin—to the standard filler that dentists use to seal off a tooth’s root. Not only are these nanodiamonds extremely strong, they have unique properties that make them very attractive vehicles for delivering drugs, including antimicrobials that help fight infections of the sealed root canal.