eating

Changes in Normal Brain Connections Linked to Eating Disorders

Posted on by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

Anyone who has ever had a bad habit knows how vexingly difficult breaking it can be. The reason is the repeated action, initially linked to some type of real or perceived reward, over time changes the way our very brains are wired to work. The bad habit becomes automatic, even when the action does us harm or we no longer wish to do it.

Now an intriguing new study shows that the same bundled nerve fibers, or brain circuits, involved in habit formation also can go awry in people with eating disorders. The findings may help to explain why eating disorders are so often resistant to will power alone. They also may help to point the way to improved approaches to treating eating disorders, suggesting strategies that adjust the actual brain circuitry in helpful ways.

These latest findings, published in the journal Science Translational Medicine, come from the NIH-supported Casey Halpern, University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine, Philadelphia, and Cara Bohon, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA [1].

Halpern, Bohon, and colleagues were interested in a growing body of evidence linking habitual behaviors to mental health conditions, most notably substance use disorders and addictions. But what especially intrigued them was recent evidence also suggesting a possible role for habitual behaviors in the emergence of eating disorders.

To look deeper into the complex circuitry underlying habit formation and any changes there that might be associated with eating disorders, they took advantage of a vast collection of data from the NIH-funded Human Connectome Project (HCP). It was completed several years ago and now serves as a valuable online resource for researchers.

The HCP offers a detailed wiring map of a normal human brain. It describes all the structural and functional neural connections based on careful analyses of hundreds of high-resolution brain scans. These connections are then layered with genetic, behavioral, and other types of data. This incredible map now allows researchers to explore and sometimes uncover the roots of neurological and mental health conditions within the brain’s many trillions of connections.

In the new study, Halpern, Bohon, and colleagues did just that. First, they used sophisticated mapping methods in 178 brain scans from the HCP data to locate key portions of a brain region called the striatum, which is thought to be involved in habit formation. What they really wanted to know was whether circuits operating within the striatum were altered in some way in people with binge eating disorder or bulimia nervosa.

To find out, the researchers recruited 34 women who have an eating disorder and, with their consent, imaged their brains using a variety of techniques. Twenty-one participants were diagnosed with binge eating disorder, and 13 had bulimia nervosa. For comparison purposes, the researchers looked at the same brain circuits in 19 healthy volunteers.

The two groups were otherwise similar in terms of their ages, weights, and other features. But the researchers suspected they might find differences between the healthy group and those with an eating disorder in brain circuits known to have links to habitual behaviors. And, indeed, they did.

In comparison to a “typical” brain, those from people with an eating disorder showed striking changes in the connectivity of a portion of the striatum known as the putamen. That’s especially notable because the putamen is known for its role in learning and movement control, including reward, thinking, and addiction. What’s more, those observed changes in the brain’s connections and circuitry in this key brain area were more evident in people whose eating disorder symptoms and emotional eating were more frequent and severe.

Using other brain imaging methods in 10 of the volunteers (eight with binge eating disorder and two healthy controls), the researchers also connected those changes in the habit-forming brain circuits to high levels of a protein receptor that responds to dopamine. Dopamine is an important chemical messenger in the brain involved in pleasure, motivation, and learning. They also observed in those with eating disorders structural changes in the architecture of the densely folded, outer layer of the brain known as grey matter.

While there’s much more to learn, the researchers note the findings may lead to future treatments aimed to modify the brain circuitry in beneficial ways. Indeed, Halpern already has encouraging early results from a small NIH-funded clinical trial testing the ability of deep brain stimulation (DBS) in people with binge eating disorder to disrupt signals that drive food cravings in another portion of the brain associated with reward and motivation, known as the nucleus accumbens, [2]. In DBS, doctors implant a pacemaker-like device capable of delivering harmless therapeutic electrical impulses deep into the brain, aiming for the spot where they can reset the abnormal circuitry that’s driving eating disorders or other troubling symptoms or behaviors.

But the latest findings published in Science Translational Medicine now suggest other mapped brain circuits as potentially beneficial DBS targets for tackling binge eating, bulimia nervosa, or other life-altering, hard-to-treat eating disorders. They also may ultimately have implications for treating other conditions involving various other forms of compulsive behavior.

These findings should come as a source of hope for the family and friends of the millions of Americans—many of them young people—who struggle with eating disorders. The findings also serve as an important reminder for the rest of us that, despite common misconceptions that disordered eating is a lifestyle choice, these conditions are in fact complex and serious mental health problems driven by fundamental changes in the brain’s underlying circuitry.

Finding new and more effective ways to treat serious eating disorders and other compulsive behaviors is a must. It will require equally serious ongoing efforts to unravel their underlying causes and find ways to alter their course—and this new study is an encouraging step in that direction.

References:

[1] Human habit neural circuitry may be perturbed in eating disorders. Wang AR, Kuijper FM, Barbosa DAN, Hagan KE, Lee E, Tong E, Choi EY, McNab JA, Bohon C, Halpern CH. Sci Transl Med. 2023 Mar 29;15(689):eabo4919.

[2] Pilot study of responsive nucleus accumbens deep brain stimulation for loss-of-control eating. Shivacharan RS, Rolle CE, Barbosa DAN, Cunningham TN, Feng A, Johnson ND, Safer DL, Bohon C, Keller C, Buch VP, Parker JJ, Azagury DE, Tass PA, Bhati MT, Malenka RC, Lock JD, Halpern CH. Nat Med. 2022 Sep;28(9):1791-1796.

Links:

Eating Disorders (National Institute of Mental Health/NIH)

Casey Halpern (Penn Medicine, Philadelphia)

Cara Bohon (Stanford University, Stanford, CA)

NIH Support: National Institute of Mental Health; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

Tracing the Neural Circuitry of Appetite

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

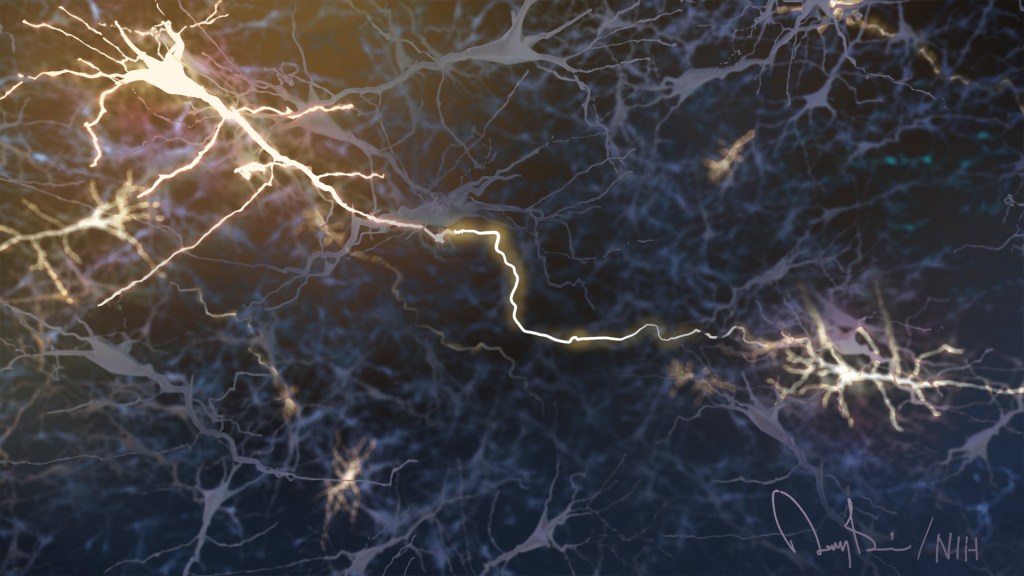

Credit: Michael Krashes, NIDDK, NIH

If you’ve ever skipped meals for a whole day or gone on a strict, low-calorie diet, you know just how powerful the feeling of hunger can be. Your stomach may growl and rumble, but, ultimately, it’s your brain that signals when to start eating—and when to stop. So, learning more about the brain’s complex role in controlling appetite is crucial to efforts to develop better ways of helping the millions of Americans afflicted with obesity [1].

Thanks to recent technological advances that make it possible to study the brain’s complex circuitry in real-time, a team of NIH-funded researchers recently made some important progress in understanding the neural basis for appetite. In a study published in the journal Nature Neuroscience, the researchers used a variety of innovative techniques to control activity in the brains of living mice, and identified one particular circuit that appears to switch hunger off and on [2].