preeclampsia

Visualizing The Placenta, a Critical but Poorly Understood Organ

Posted on by Diana W. Bianchi, M.D., Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development

The placenta is the Rodney Dangerfield of organs; it gets no respect, no respect at all. This short-lived but critical organ supports pregnancy by bringing nutrients and oxygen to the fetus, removing waste, providing immune protection, and producing hormones to support fetal development.

It also influences the lifelong health of both mother and child. Problems with the placenta can lead to preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, poor fetal growth, preterm birth, and stillbirth. Although we were all connected to one, the placenta is the least understood, and least studied, of all human organs.

What we do know about the human placenta largely comes from studying it after delivery. But that’s like studying the heart after it’s stopped beating. It doesn’t help us predict complications in time to avert a crisis.

To fill these knowledge gaps, NIH’s Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) developed the Human Placenta Project (HPP) to noninvasively study the placenta during pregnancy. Since 2014, this approximately $88 million collaborative research effort has been developing ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and blood-based biomarker methods to study how the placenta functions in real time and in greater detail.

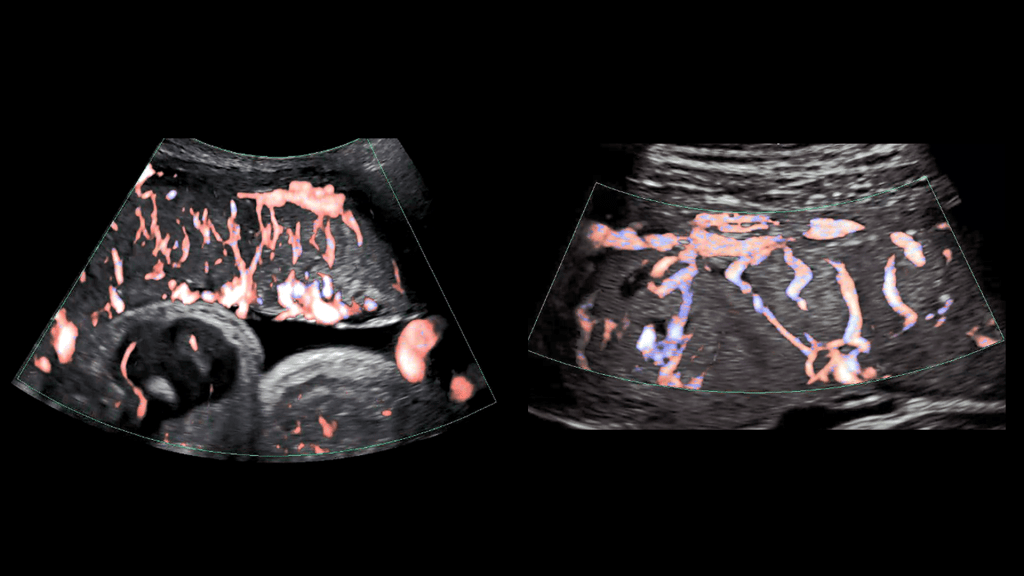

As illustrated in the image above, advanced ultrasound tools allowed HPP researchers at Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, and the University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, to gain a detailed look at the placenta’s intricate arrangement of blood vessels, or vasculature. By evaluating both fetal (left panel) and maternal (right panel) placental vasculature in 610 pregnant people starting at 13 weeks of gestation, the investigators aimed to identify early changes that predicted later complications.

They observed that such changes can start in the first trimester and affect both the vasculature and placental tissue. While further research is needed, these findings suggest that placental ultrasound monitoring can inform efforts to prevent and treat pregnancy complications.

Another HPP team led by Boston Children’s Hospital is developing an MRI strategy to monitor blood flow and oxygen transport through the placenta during pregnancy. Interpreting and visualizing MRI data of the placenta is challenging because of its variable shape, the tendency of muscles in the uterus to begin tightening or contracting well before labor [1], and other factors.

As shown in the video above, the researchers developed a way to account for the motion of the uterus and “freeze” the placenta to make it easier to study (left two panels of video) [2]. They also developed algorithms to better visualize the complex patterns of placental oxygen content during contractions (center panel) [3]. The scientists then carried out initial visualizations of blood flow through the placenta shortly after delivery (second panel from right) [4].

They now intend to map these MRI findings to the placenta itself after delivery (far right panel), which will allow them to explore how additional factors such as gene expression patterns and genetic variants contribute to placental function. Ultimately, they plan to apply these MRI techniques to monitor the placenta in real time during pregnancy and identify changes that indicate compromised function early enough to adjust maternal management as needed.

Other HPP efforts focus on identifying components in maternal blood that reflect the status of the placenta. For example, an HPP research team led by scientists at the University of California, Los Angeles, adapted non-invasive prenatal testing methods to analyze genetic material shed from the placenta into the maternal bloodstream. Their findings suggest that distinctive patterns in this genetic material detected early in pregnancy may indicate risk for later complications [5].

Another HPP team, led by investigators at Columbia University, New York, helped establish that extracellular RNAs (exRNAs) released by the placenta into maternal circulation reflect the placenta’s status at a cellular level beginning in the first trimester. To harness the potential of exRNA biomarkers, the investigators are optimizing methods to isolate, sequence, and analyze exRNAs in maternal blood.

These are just a few examples of the cutting-edge work being funded through the HPP, which complements NICHD’s longstanding investment in basic research to unravel the physiology of and real-time gene expression in the placenta. Unlocking the secrets of the placenta may one day help us to prevent and treat a range of common pregnancy complications, while also providing insights into other areas of science and medicine such as cardiovascular disease and aging. NICHD is committed to giving this important organ the respect it deserves.

References:

[1] Placental MRI: Effect of maternal position and uterine contractions on placental BOLD MRI measurements. Abaci Turk E, Abulnaga SM, Luo J, Stout JN, Feldman H, Turk A, Gagoski B, Wald LL, Adalsteinsson E, Roberts DJ, Bibbo C, Robinson JN, Golland P, Grant PE, Barth, Jr WH. Placenta. 2020 Jun 1; 95: 69-77.

[2] Spatiotemporal alignment of in utero BOLD-MRI series. Turk EA, Luo J, Gagoski B, Pascau J, Bibbo C, Robinson JN, Grant PE, Adalsteinsson E, Golland P, Malpica N. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2017 Aug;46(2):403-412.

[3] Volumetric parameterization of the placenta to a flattened template. Abulnaga SM, Turk EA, Bessmeltsev M, Grant PE, Solomon J, Golland P. IEEE transactions on medical imaging. 2022 April;41(4):925-936.

[4] Placental MRI: development of an MRI compatible ex vivo system for whole placenta dual perfusion. Stout JN, Rouhani S, Turk EA, Ha CG, Luo J, Rich K, Wald LL, Adalsteinsson E, Barth, Jr WH, Grant PE, Roberts DJ. Placenta. 2020 Nov 1; 101: 4-12.

[5] Cell-free DNA methylation and transcriptomic signature prediction of pregnancies with adverse outcomes. Del Vecchio G, Li Q, Li W, Thamotharan S, Tosevska A, Morselli M, Sung K, Janzen C, Zhou X, Pellegrini M, Devaskar SU. Epigenetics. 2021 Jun;16(6):642-661.

Links:

Human Placenta Project (Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development/NIH)

Preeclampsia (NICHD)

Understanding Gestational Diabetes (NICHD)

Preterm Labor and Birth (NICHD)

Stillbirth (NICHD)

Abuhamad Project Information (NIH RePORTER)

Grant Project Information (NIH RePORTER)

Devaskar Project Information (NIH RePORTER)

Williams Project Information (NIH RePORTER)

Note: Acting NIH Director Lawrence Tabak has asked the heads of NIH’s Institutes and Centers (ICs) to contribute occasional guest posts to the blog to highlight some of the interesting science that they support and conduct. This is the 10th in the series of NIH IC guest posts that will run until a new permanent NIH director is in place.

Vast Majority of Pregnant Women with COVID-19 Won’t Have Complications, Study Finds

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

It’s natural and highly appropriate for women to be concerned about their health and the wellbeing of their unborn babies during pregnancy. With the outbreak of the pandemic, those concerns have only increased, especially after a study found last spring that about 30 percent of pregnant women who become infected with SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, needed to be hospitalized [1].

But that early study didn’t clearly divide out hospitalizations that were due to pregnancy from those owing to complications of COVID-19. Now, a large, observational study has taken a more comprehensive look at the issue and published some reassuring news for parents-to-be: the vast majority of women who test positive for COVID-19 during their pregnancies won’t develop serious health complications [2]. What’s more, it’s also unlikely that their newborns will become infected with SARS-CoV-2.

The findings reported in JAMA Network Open come from a busy prenatal clinic that serves women who are medically indigent at Parkland Health and Hospital System, affiliated with the University of Texas Southwestern, Dallas. Researchers there, led by obstetrician Emily Adhikari, followed more than 3,300 pregnant women, most of whom were Hispanic (75 percent) or African American (14 percent). From March through August of this year, 252 women tested positive for COVID-19 during their pregnancies.

At diagnosis, 95 percent were asymptomatic or had only mild symptoms. Only 13 of the 252 COVID-19-positive women (5 percent) in the study developed severe or critical pneumonia, including just six with no or mild symptoms initially. Only 14 women (6 percent) were admitted to the hospital for management of their COVID-19 pneumonia, and all survived.

By comparing mothers with and without COVID-19 during pregnancy, the researchers found there was no increase in adverse pregnancy-related outcomes. Overall, women with COVID-19 during pregnancy were not more likely to give birth early on average. They weren’t at increased risk of dangerous preeclampsia, a pregnancy complication characterized by high blood pressure and organ damage, or an emergency C-section to protect the baby.

The researchers found no evidence that the placenta was compromised in any way by the SARS-CoV-2 infection. In most cases, newborns didn’t get sick. Only 6 of 188 infants (3 percent) tested positive for COVID-19. Most of those infected were born to mothers who were asymptomatic or had only mild illness.

This is all encouraging news. However, it is worth noting that mothers who developed severe COVID-19 before reaching 37 weeks, or well into the third trimester of pregnancy, were more likely to give birth prematurely. More research is needed, but the study also suggests that diabetes may increase the risk for severe COVID-19 in pregnancy.

This study’s bottom line is that most women who become infected with SARS-CoV-2 during pregnancy will do just fine. That doesn’t mean, however, that anyone should take this situation casually. The finding that 5 percent of pregnant women may become severely ill is still cause for concern. Plus not all researchers come to the same conclusion—an update to the first study cited in this post recently found a greater risk for pregnant women becoming severely ill from COVID-19 and giving birth prematurely.

Taken together, while there’s no need to panic about COVID-19 infection during pregnancy, it’s still a good idea for pregnant women and their loved ones to take extra precautions to protect their health. And, of course, follow the three W’s: Wear a mask, Watch your distance, and Wash your hands.

References:

[1] Characteristics of women of reproductive age with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection by pregnancy status—United States, January 22–June 7, 2020. CDC COVID-19 Response Team. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020 Mar 27;69(12):343-346.

[2] Pregnancy outcomes among women with and without severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. Adhikari EH, Moreno W, Zofkie AC, MacDonald L, McIntire DD, Collins RRJ, Spong CY. JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Nov 2;3(11):e2029256.

Links:

Coronavirus (COVID) (NIH)

Combat COVID (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Washington, D.C.)

Data on COVID-19 during Pregnancy: Severity of Maternal Illness (Centers for Disease Control and Prevent, Atlanta)

COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines: Special Considerations in Pregnancy (NIH)

Emily Adhikari (University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas)

Preeclampsia: Study Highlights Need for More Effective Treatment, Prevention

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Thinkstock

It’s well known that preeclampsia, a condition characterized by a progressive rise in a pregnant woman’s blood pressure and appearance of protein in the urine, can have negative, even life-threatening impacts on the health of both mother and baby. Now, NIH-funded researchers have documented that preeclampsia is also taking a very high toll on our nation’s economic well-being. In fact, their calculations show that, in 2012 alone, preeclampsia-related care cost the U.S. health care system more than $2 billion.

These findings are especially noteworthy because preeclampsia rates in the United States have been steadily rising over the past 30 years, fueled in part by increases in average maternal age and weight. This highlights the urgent need for more research to develop new and more effective strategies to protect the health of all mothers and their babies.