devices

Giving Thanks for Biomedical Research

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

This Thanksgiving, Americans have an abundance of reasons to be grateful—loving family and good food often come to mind. Here’s one more to add to the list: exciting progress in biomedical research. To check out some of that progress, I encourage you to watch this short video, produced by NIH’s National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Engineering (NIBIB), that showcases a few cool gadgets and devices now under development.

Among the technological innovations is a wearable ultrasound patch for monitoring blood pressure [1]. The patch was developed by a research team led by Sheng Xu and Chonghe Wang, University of California San Diego, La Jolla. When this small patch is worn on the neck, it measures blood pressure in the central arteries and veins by emitting continuous ultrasound waves.

Other great technologies featured in the video include:

• Laser-Powered Glucose Meter. Peter So and Jeon Woong Kang, researchers at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Cambridge, and their collaborators at MIT and University of Missouri, Columbia have developed a laser-powered device that measures glucose through the skin [2]. They report that this device potentially could provide accurate, continuous glucose monitoring for people with diabetes without the painful finger pricks.

• 15-Second Breast Scanner. Lihong Wang, a researcher at California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, and colleagues have combined laser light and sound waves to create a rapid, noninvasive, painless breast scan. It can be performed while a woman rests comfortably on a table without the radiation or compression of a standard mammogram [3].

• White Blood Cell Counter. Carlos Castro-Gonzalez, then a postdoc at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, and colleagues developed a portable, non-invasive home monitor to count white blood cells as they pass through capillaries inside a finger [4]. The test, which takes about 1 minute, can be carried out at home, and will help those undergoing chemotherapy to determine whether their white cell count has dropped too low for the next dose, avoiding risk for treatment-compromising infections.

• Neural-Enabled Prosthetic Hand (NEPH). Ranu Jung, a researcher at Florida International University, Miami, and colleagues have developed a prosthetic hand that restores a sense of touch, grip, and finger control for amputees [5]. NEPH is a fully implantable, wirelessly controlled system that directly stimulates nerves. More than two years ago, the FDA approved a first-in-human trial of the NEPH system.

If you want to check out more taxpayer-supported innovations, take a look at NIBIB’s two previous videos from 2013 and 2018 As always, let me offer thanks to you from the NIH family—and from all Americans who care about the future of their health—for your continued support. Happy Thanksgiving!

References:

[1] Monitoring of the central blood pressure waveform via a conformal ultrasonic device. Wang C, Li X, Hu H, Zhang, L, Huang Z, Lin M, Zhang Z, Yun Z, Huang B, Gong H, Bhaskaran S, Gu Y, Makihata M, Guo Y, Lei Y, Chen Y, Wang C, Li Y, Zhang T, Chen Z, Pisano AP, Zhang L, Zhou Q, Xu S. Nature Biomedical Engineering. September 2018, 687-695.

[2] Evaluation of accuracy dependence of Raman spectroscopic models on the ratio of calibration and validation points for non-invasive glucose sensing. Singh SP, Mukherjee S, Galindo LH, So PTC, Dasari RR, Khan UZ, Kannan R, Upendran A, Kang JW. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2018 Oct;410(25):6469-6475.

[3] Single-breath-hold photoacoustic computed tomography of the breast. Lin L, Hu P, Shi J, Appleton CM, Maslov K, Li L, Zhang R, Wang LV. Nat Commun. 2018 Jun 15;9(1):2352.

[4] Non-invasive detection of severe neutropenia in chemotherapy patients by optical imaging of nailfold microcirculation. Bourquard A, Pablo-Trinidad A, Butterworth I, Sánchez-Ferro Á, Cerrato C, Humala K, Fabra Urdiola M, Del Rio C, Valles B, Tucker-Schwartz JM, Lee ES, Vakoc BJ9, Padera TP, Ledesma-Carbayo MJ, Chen YB, Hochberg EP, Gray ML, Castro-González C. Sci Rep. 2018 Mar 28;8(1):5301.

[5] Enhancing Sensorimotor Integration Using a Neural Enabled Prosthetic Hand System

Links:

Sheng Xu Lab (University of California San Diego, La Jolla)

So Lab (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge)

Lihong Wang (California Institute of Technology, Pasadena)

Video: Lihong Wang: Better Cancer Screenings

Carlos Castro-Gonzalez (Madrid-MIT M + Visión Consortium, Cambridge, MA)

Video: Carlos Castro-Gonzalez (YouTube)

Ranu Jung (Florida International University, Miami)

Video: New Prosthetic System Restores Sense of Touch (Florida International)

NIH Support: National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering; National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Cancer Institute; Common Fund

Wearable Ultrasound Patch Monitors Blood Pressure

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

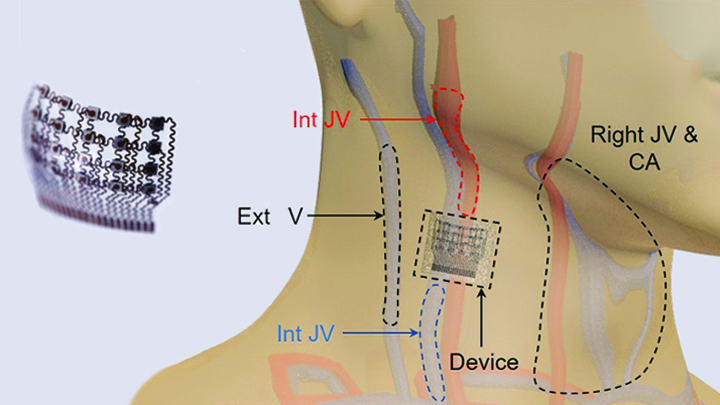

Caption: Worn on the neck, the device records central blood pressure in the carotid artery (CA), internal jugular vein (Int JV) and external jugular vein (Ext JV).

Credit: Adapted from Wang et al, Nature Biomedical Engineering

There’s lots of excitement out there about wearable devices quietly keeping tabs on our health—morning, noon, and night. Most wearables monitor biological signals detectable right at the surface of the skin. But, the sensing capabilities of the “skin” patch featured here go far deeper than that.

As described recently in Nature Biomedical Engineering, when this small patch is worn on the neck, it measures blood pressure way down in the central arteries and veins more than an inch beneath the skin [1]. The patch works by emitting continuous ultrasound waves that monitor subtle, real-time changes in the shape and size of pulsing blood vessels, which indicate rises or drops in pressure.

Honoring Our Promise: Clinical Trial Data Sharing

Posted on by Drs. Kathy L. Hudson and Francis S. Collins

When people enroll in clinical trials to test new drugs, devices, or other interventions, they’re often informed that such research may not benefit them directly. But they’re also told what’s learned in those clinical trials may help others, both now and in the future. To honor these participants’ selfless commitment to advancing biomedical science, researchers have an ethical obligation to share the results of clinical trials in a swift and transparent manner.

When people enroll in clinical trials to test new drugs, devices, or other interventions, they’re often informed that such research may not benefit them directly. But they’re also told what’s learned in those clinical trials may help others, both now and in the future. To honor these participants’ selfless commitment to advancing biomedical science, researchers have an ethical obligation to share the results of clinical trials in a swift and transparent manner.

But that’s not the only reason why sharing data from clinical trials is so important. Prompt dissemination of clinical trial results is essential for guiding future research. Furthermore, resources can be wasted and people may even stand to be harmed if the results of clinical trials are not fully disclosed in a timely manner. Without access to complete information about previous clinical trials—including data that are negative or inconclusive, researchers may launch similar studies that put participants at needless risk or expose them to ineffective interventions. And, if conclusions are distorted by failure to report results, incomplete knowledge can eventually make its way into clinical guidelines and, thereby, affect the care of a great many patients [1].