2019 Green Fluorescent Protein Image and Video Contest

Finding Beauty in Cell Stress

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Most stressful situations that we experience in daily life aren’t ones that we’d choose to repeat. But the cellular stress response captured in this video is certainly worth repeating a few times, so you can track what happens when two cancer cells get hit with stressors.

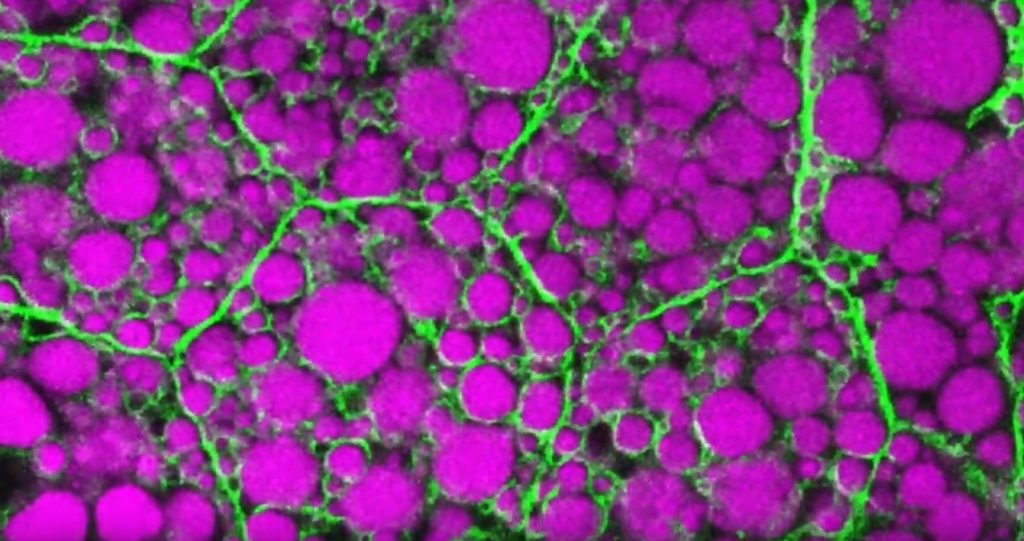

In this movie of two highly stressed osteosarcoma cells, you first see the appearance of many droplet-like structures (green). This is followed by a second set of droplets (magenta) and, finally, the fusion of both types of droplets.

These droplets are composed of fluorescently labeled stress-response proteins, either G3BP or UBQLN2 (Ubiquilin-2). Each protein is undergoing a fascinating process, called phase separation, in which a non-membrane bound compartment of the cytoplasm emerges and constrains the motion of proteins within it. Subsequently, the proteins fuse with like proteins to form larger droplets, in much the same way that raindrops merge on a car’s windshield.

Julia Riley, an undergraduate student in the NIH-supported lab of Heidi Hehnly and lab of Carlos Castañeda, Syracuse University, NY, shot this movie using the sophisticated tools of fluorescence microscopy. It’s the next installment in our series featuring winners of the 2019 Green Fluorescent Protein Image and Video Contest, sponsored by the American Society for Cell Biology. The contest honors the discovery of green fluorescent protein (GFP), which—together with a rainbow of other fluorescent proteins—has enabled researchers to visualize proteins and their dynamic activities inside cells for the last 25 years.

Riley and colleagues suspect that, in this case, phase separation is a protective measure that allows proteins to wall themselves off from the rest of the cell during stressful conditions. In this way, the proteins can create new functional units within the cell. The researchers are working to learn much more about what this interesting behavior entails as a basic organizing principle in the cell and how it works.

Even more intriguing is that similar stress-responding proteins are commonly altered in people with the devastating neurologic condition known as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). ALS is a group of rare neurological diseases that involve the progressive deterioration of neurons responsible for voluntary movements such as chewing, walking, and talking. There’s been the suggestion that these phase separation droplets may seed the formation of the larger protein aggregates that accumulate in the motor neurons of people with this debilitating and fatal condition.

Castañeda and Hehnly, working with J. Paul Taylor at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, earlier reported that Ubiquilin-2 forms stress-induced droplets in multiple cell types [1]. More recently, they showed that mutations in Ubiquilin-2 have been linked to ALS changes in the way that the protein undergoes phase separation in a test tube [2].

While the proteins in this award-winning video aren’t mutant forms, Riley is now working on the sequel, featuring versions of the Ubiquilin-2 protein that you’d find in some people with ALS. She hopes to capture how those mutations might produce a different movie and what that might mean for understanding ALS.

References:

[1] Ubiquitin Modulates Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation of UBQLN2 via Disruption of Multivalent Interactions. Dao TP, Kolaitis R-M, Kim HJ, O’Donovan K, Martyniak B, Colicino E, Hehnly H, Taylor JP, Castañeda CA. Molecular Cell. 2018 Mar 15;69(6):965-978.e6.

[2] ALS-Linked Mutations Affect UBQLN2 Oligomerization and Phase Separation in a Position- and Amino Acid-Dependent Manner. Dao TP, Martyniak B, Canning AJ, Lei Y, Colicino EG, Cosgrove MS, Hehnly H, Castañeda CA. Structure. 2019 Jun 4;27(6):937-951.e5.

Links:

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke/NIH)

Castañeda Lab (Syracuse University, NY)

Hehnly Lab (Syracuse University)

Green Fluorescent Protein Image and Video Contest (American Society for Cell Biology, Bethesda, MD)

2008 Nobel Prize in Chemistry (Nobel Foundation, Stockholm, Sweden)

NIH Support: National Institute of General Medical Sciences

The Perfect Cytoskeletal Storm

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Ever thought about giving cell biology a whirl? If so, I suggest you sit down and take a look at this full-blown cytoskeletal “storm,” which provides a spectacular dynamic view of the choreography of life.

Before a cell divides, it undergoes a process called mitosis that copies its chromosomes and produces two identical nuclei. As part of this process, microtubules, which are structural proteins that help make up the cell’s cytoskeleton, reorganize the newly copied chromosomes into a dense, football-shaped spindle. The position of this mitotic spindle tells the cell where to divide, allowing each daughter cell to contain its own identical set of DNA.

To gain a more detailed view of microtubules in action, researchers designed an experimental system that utilizes an extract of cells from the African clawed frog (Xenopus laevis). As the video begins, a star-like array of microtubules (red) radiate outward in an apparent effort to prepare for cell division. In this configuration, the microtubules continually adjust their lengths with the help of the protein EB-1 (green) at their tips. As the microtubules grow and bump into the walls of a lab-generated, jelly-textured enclosure (dark outline), they buckle—and the whole array then whirls around the center.

Abdullah Bashar Sami, a Ph.D. student in the NIH-supported lab of Jesse “Jay” Gatlin, University of Wyoming, Laramie, shot this movie as a part his basic research to explore the still poorly understood physical forces generated by microtubules. The movie won first place in the 2019 Green Fluorescent Protein Image and Video Contest sponsored by the American Society for Cell Biology. The contest honors the 25th anniversary of the discovery of green fluorescent protein (GFP), which transformed cell biology and earned the 2008 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for three scientists who had been supported by NIH.

Like many movies, the setting was key to this video’s success. The video was shot inside a microfluidic chamber, designed in the Gatlin lab, to study the physics of microtubule assembly just before cells divide. The tiny chamber holds a liquid droplet filled with the cell extract.

When the liquid is exposed to an ultra-thin beam of light, it forms a jelly-textured wall, which traps the molecular contents inside [1]. Then, using time-lapse microscopy, the researchers watch the mechanical behavior of GFP-labeled microtubules [2] to see how they work to position the mitotic spindle. To do this, microtubules act like shapeshifters—scaling to adjust to differences in cell size and geometry.

The Gatlin lab is continuing to use their X. laevis system to ask fundamental questions about microtubule assembly. For many decades, both GFP and this amphibian model have provided cell biologists with important insights into the choreography of life, and, as this work shows, we can expect much more to come!

References:

[1] Microtubule growth rates are sensitive to global and local changes in microtubule plus-end density. Geisterfer ZM, Zhu D, Mitchison T, Oakey J, Gatlin JC. November 20, 2019.

[2] Tau-based fluorescent protein fusions to visualize microtubules. Mooney P, Sulerud T, Pelletier JF, Dilsaver MR, et al. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken). 2017 Jun;74(6):221-232.

Links:

Mitosis (National Human Genome Research Institute/NIH)

Gatlin Lab (University of Wyoming, Laramie)

Green Fluorescent Protein Image and Video Contest (American Society for Cell Biology, Bethesda, MD)

2008 Nobel Prize in Chemistry (Nobel Foundation, Stockholm, Sweden)

NIH Support: National Institute of General Medical Sciences