gene signature

Working Toward Greater Precision in Childhood Cancers

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: National Cancer Institute, NIH

Each year, more than 15,000 American children and teenagers will be diagnosed with cancer. While great progress has been made in treating many types of childhood cancer, it remains the leading cause of disease-related death among kids who make it past infancy in the United States [1]. One reason for that sobering reality is our relatively limited knowledge about the precise biological mechanisms responsible for childhood cancers—information vital for designing targeted therapies to fight the disease in all its varied forms.

Now, two complementary studies have brought into clearer focus the genomic landscapes of many types of childhood cancer [2, 3]. The studies, which analyzed DNA data representing tumor and normal tissue from more than 2,600 young people with cancer, uncovered thousands of genomic alterations in about 200 different genes that appear to drive childhood cancers. These so-called “driver genes” included many that were different than those found in similar studies of adult cancers, as well as a considerable number of mutations that appear amenable to targeting with precision therapies already available or under development.

Lyme Disease: Gene Signatures May Catch the Infection Sooner

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

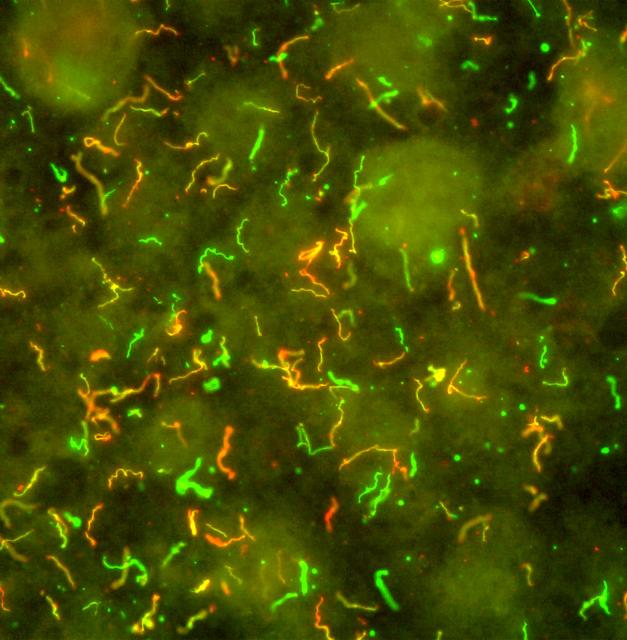

Caption: Borrelia burgdorferi. Immunofluorescent antibodies bind to surface proteins on the bacterium that causes Lyme disease, producing fluorescent yellow, red, and green hues.

Credit: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

Each year, thousands of Americans are bitten by deer ticks.These tiny ticks, common in and around wooded areas in some parts of the United States, can transmit a bacterium into the bloodstream that causes Lyme disease. Those infected experience fever, headache, stiff necks, body aches, and fatigue. A characteristic circular “target” red rash can mark the site of the tick bite, but isn’t always noticed. In fact, many people don’t realize that they’ve been bitten, and weeks can pass before they see a doctor. By then the infection has spread, sometimes causing additional rashes and/or neurological, cardiac, and rheumatological symptoms that mimic those of other conditions. All of this can make getting the right diagnosis frustrating, especially in areas where Lyme disease is rare.

Even when Lyme disease is suspected early on, the bacterium is unusually slow growing and present at low levels, so it can take a while before blood tests detect antibodies to confirm the condition. By then, knocking out the infection with antibiotics can be more challenging. But research progress continues to be made toward improving the diagnosis of Lyme disease.

An NIH-supported team recently uncovered a unique gene expression pattern in white blood cells from people infected with the Lyme disease-causing bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi [1]. This distinctive early gene signature, which persists after antibiotic treatment, is unique from other viral and bacterial illnesses studies by the team. With further work and validation, the test could one day possibly provide a valuable new tool to help doctors diagnose Lyme disease earlier and help more people get the timely treatment that they need.

Gene Expression Test Aims to Reduce Antibiotic Overuse

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: Duke physician-scientist Ephraim Tsalik assesses a patient for a respiratory infection.

Credit: Shawn Rocco/Duke Health

Without doubt, antibiotic drugs have saved hundreds of millions of lives from bacterial infections that would have otherwise been fatal. But their inappropriate use has led to the rise of antibiotic-resistant superbugs, which now infect at least 2 million Americans every year and are responsible for thousands of deaths [1]. I’ve just come from the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, where concerns about antibiotic resistance and overuse was a topic of conversation. In fact, some of the world’s biggest pharmaceutical companies issued a joint declaration at the forum, calling on governments and industry to work together to combat this growing public health threat [2].

Many people who go to the doctor suffering from respiratory symptoms expect to be given a prescription for antibiotics. Not only do such antibiotics often fail to help, they serve to fuel the development of antibiotic-resistant superbugs [3]. That’s because antibiotics are only useful in treating respiratory illnesses caused by bacteria, and have no impact on those caused by viruses (which are frequent in the wintertime). So, I’m pleased to report that a research team, partially supported by NIH, recently made progress toward a simple blood test that analyzes patterns of gene expression to determine if a patient’s respiratory symptoms likely stem from a bacterial infection, viral infection, or no infection at all.

In contrast to standard tests that look for signs of a specific infectious agent—respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) or the influenza virus, for instance—the new strategy casts a wide net that takes into account changes in the patterns of gene expression in the bloodstream, which differ depending on whether a person is fighting off a bacterial or a viral infection. As reported in Science Translational Medicine [4], Geoffrey Ginsburg, Christopher Woods, and Ephraim Tsalik of Duke University’s Center for Applied Genomics and Precision Medicine, Durham, NC, and their colleagues collected blood samples from 273 people who came to the emergency room (ER) with signs of acute respiratory illness. Standard diagnostic tests showed that 70 patients arrived in the ER with bacterial infections and 115 were battling viruses. Another 88 patients had no signs of infection, with symptoms traced instead to other health conditions.

Gene Signature Predicts Aspirin Resistance

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: New blood test of gene activity reveals who will respond to aspirin therapy and who won’t.

Source: Duke Medicine

About 60 million Americans take an aspirin a day to reduce the risk of strokes and heart attacks. But for 10 to 30% of those who follow this recommendation, this preventive therapy turns out not to offer any protection. An NIH-funded team, based at Duke University Medical Center, has discovered a set of blood markers that predict who will benefit from aspirin therapy and who will not [1].

First of all, I’ve got to tell you that acetylsalicylic acid, the scientific name for aspirin, is a pretty amazing drug. German chemist Felix Hoffmann synthesized the first commercial form of the drug more than a hundred years ago to treat headaches, minor aches and pains, and fever—and we’re still discovering nuances about how the drug works, for whom, and for which diseases.