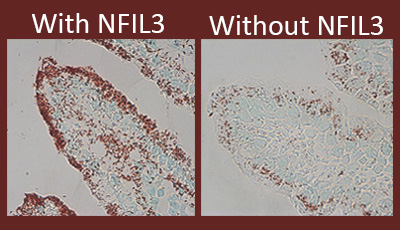

Caption: Lipids (red) inside mouse intestinal cells with and without NFIL3.

Credit: Lora V. Hooper, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas

The American epidemic of obesity is a major public health concern, and keeping off the extra pounds is a concern for many of us. Yet it can also be a real challenge for people who may eat normally but get their days and nights mixed up, including night-shift workers and those who regularly travel overseas. Why is that?

The most obvious reason is the odd hours throw a person’s 24-hour biological clock—and metabolism—out of sync. But an NIH-funded team of researchers has new evidence in mice to suggest the answer could go deeper to include the trillions of microbes that live in our guts—and, more specifically, the way they “talk” to intestinal cells. Their studies suggest that what gut microbes “say” influences the activity of a key clock-driven protein called NFIL3, which can set intestinal cells up to absorb and store more fat from the diet while operating at hours that might run counter to our fixed biological clocks.

NFIL3 is a transcription factor, a protein that switches certain genes on and off. Earlier studies had focused on its role in immune cells, but a team led by Lora Hooper at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, discovered that NFIL3 is also found in cells in the inner lining, or epithelium, of the mouse small intestine.

Intriguingly, as reported recently in the journal Science [1], they noticed that NFIL3 levels were much lower in the intestines of “germ-free” mice that don’t have any gut microbes. That information suggested that the NFIL3 transcription factor responds to gut microbes, and raised an obvious question: What else does NFIL3 do in intestinal cells?

To find out, Hooper and colleagues generated mice that lacked the Nfil3 gene only in epithelial cells. When those animals were raised on normal mouse chow, they grew leaner than their normal littermates.

When both groups were placed on a high-fat diet, the mice lacking NFIL3 in their intestines packed on a lot less weight. They also had lower body fat and other indications of better health, including lower blood lipids, less fat in the liver, and fewer early signs of diabetes.

This brought them somewhat unexpectedly to the fascinating area of circadian biology. Many metabolic pathways are synchronized to day-and-night cycles that oscillate between greater activity during daylight and reduced activity at night. Orchestrating this 24-hour cycle is a core network of transcription factors called “the circadian clock” that modulate the expression of numerous genes, including Nfil3, over the course of the day [2].

The circadian clock, however, doesn’t operate in isolation. Recent studies suggest gut microbes interact with these transcription factors to affect metabolism profoundly [3]. That’s why it was interesting when the researchers followed up and established that the absence of gut microbes in germ-free mice caused NFIL3 levels to flatten out, losing the protein’s normal 24-hour rhythm and suggesting its expression is dependent on the microbes.

What might this mean for fat storage and weight gain? For clues, the researchers delved deeper into the basic biology, comparing the activity of other genes in intestinal cells with and without NFIL3. They uncovered differences in the activity of 33 genes, many of which follow a regular daily rhythm. Seventeen of those genes were already known to encode proteins involved in the uptake of lipids or other aspects of metabolism.

It looked as though mice lacking NFIL3 might be leaner because their intestinal cells take up and store less fat from the diet. To nail down this point, the researchers used a red stain to visualize lipids in the animals’ intestines. As shown above, intestinal cells lacking NFIL3 contained much less lipid and the extra fat passed right on through the digestive systems of the mice.

Further studies showed gut microbes don’t talk directly to intestinal cells and NFIL3. Rather, they go through an intermediary, sending messages to intestinal cells via the immune system. In other words, it’s complicated. But based on their work, the researchers say NFIL3 seems to be “an essential molecular link” among the circadian clock, microbes, and metabolism.

Of course, these findings are in mice. But humans are known to have NFIL3, too, and further research will be needed to chase down this potentially important lead. If confirmed, it could offer new clues as to why some people are leaner than others, and might suggest new ways of preventing or treating an array of metabolic conditions, including obesity, diabetes, and heart disease.

References:

[1] The intestinal microbiota regulates body composition through NFIL3 and the circadian clock. Wang Y, Kuang Z, Yu X, Ruhn KA, Kubo M, Hooper LV. Science. 2017 Sep 1;357(6354):912-916.

[2] Antagonistic role of E4BP4 and PAR proteins in the circadian oscillatory mechanism. Mitsui S, Yamaguchi S, Matsuo T, Ishida Y, Okamura H. Genes Dev. 2001 Apr 15;15(8):995-1006.

[3] Transkingdom control of microbiota diurnal oscillations promotes metabolic homeostasis. Thaiss CA, Zeevi D, Levy M, Zilberman-Schapira G, Suez J, Tengeler AC, Abramson L, Katz MN, Korem T, Zmora N, Kuperman Y, Biton I, Gilad S, Harmelin A, Shapiro H, Halpern Z, Segal E, Elinav E. Cell. 2014 Oct 23;159(3):514-529.

Links:

Understanding Adult Overweight and Obesity (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases/NIH)

Hooper Lab (University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas)

NIH Support: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases