One Nation in Support of Biomedical Research?

Posted on by Dr. Sally Rockey and Dr. Francis Collins

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times.” Until recently, we’d never have dreamed of mentioning the famous opening line of Charles Dickens’ Tale of Two Cities in the context of U.S. biomedical research. But now those words ring all too true.

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times.” Until recently, we’d never have dreamed of mentioning the famous opening line of Charles Dickens’ Tale of Two Cities in the context of U.S. biomedical research. But now those words ring all too true.

The “best of times” reflects the amazing technological advances and unprecedented scientific opportunities that exist right now. We’ve never had a better chance to make rapid progress in preventing, diagnosing, and curing human disease. But the “worst of times” is the other reality: NIH’s ability to support vital research at more than 2,500 universities and organizations across the nation is reeling from a decline in funding that threatens our health, our economy, and our standing as the world leader in biomedical innovation.

After 10 years of essentially flat budgets eroded by the effects of inflation, and now precipitously worsened by the impact of sequestration (an automatic, across-the-board 5.5% cut in NIH support), NIH’s purchasing power has been cut by almost 25% compared to a decade ago.

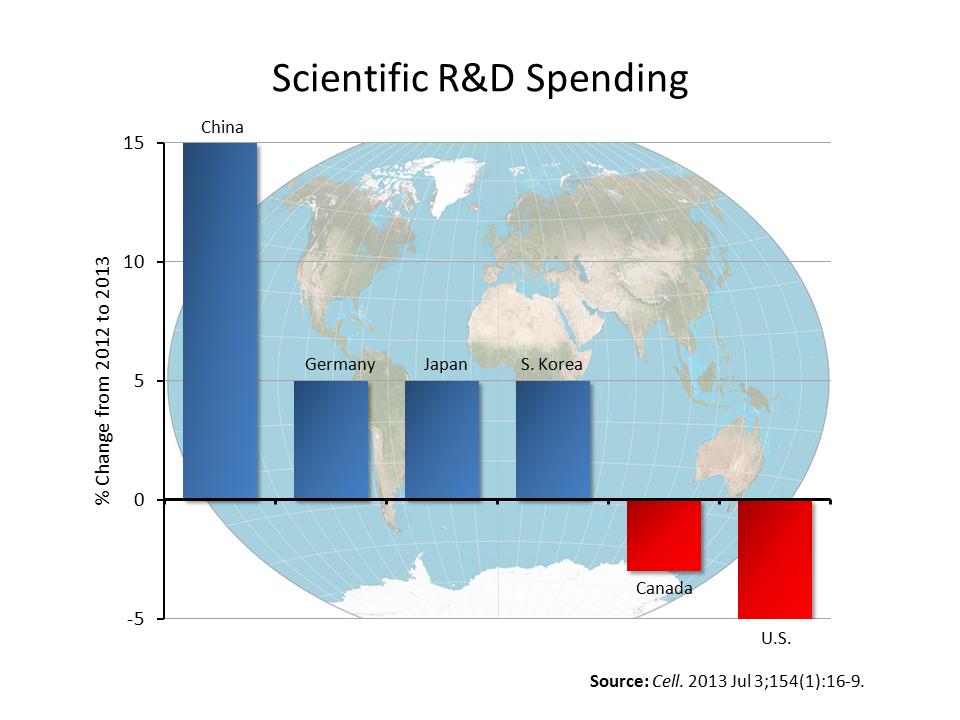

Ironically, the United States is slashing its R&D spending at a time when other nations are significantly boosting theirs—as you can see in the bar graph featured in this post. It appears that global competitors have read our playbook, noted how U.S. biomedical innovation has helped to fuel our economic growth over the past 60 years and are now ramping up their efforts to emulate our success. Or, if we may quote Dickens again, “It was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness.”

Unfortunately, the drama that NIH-supported science faces today is not a Dickens novel. It’s very real. The progressively worsening budget situation has the potential to inflict profound, long-term damage to U.S. scientific momentum and morale.

Imagine yourself as a visionary young scientist at one of our nation’s research universities. You have many exciting ideas. You write up the most promising and send the grant application to NIH in hopes of being supported. But you find it increasingly difficult to remain optimistic or to see a future in this field when you look at the steep odds of being funded. Currently, a grant application has a less than one chance in six of being successful—a troubling trend that’s detailed in the line graph below.

Because of sequester, NIH will be funding 650 fewer research grants than it did last fiscal year. Nearly a quarter of those unfunded applications have come from scientists who’d already made substantial progress in earlier grant awards and were hoping to renew them. Peer reviewers judged their research in the top 17% of all applications received, but they will now have to stop ongoing research projects—meaning, in this double tragedy, we will lose both previous and future research investments.

Because of sequester, NIH will be funding 650 fewer research grants than it did last fiscal year. Nearly a quarter of those unfunded applications have come from scientists who’d already made substantial progress in earlier grant awards and were hoping to renew them. Peer reviewers judged their research in the top 17% of all applications received, but they will now have to stop ongoing research projects—meaning, in this double tragedy, we will lose both previous and future research investments.

If sequestration continues for a full 10 years, the outlook for the U.S. biomedical research enterprise turns downright grim. NIH will lose a staggering $19 billion, and, with it, our nation will lose an untold amount of precious time in its race against Alzheimer’s disease, cancer, arthritis, asthma, autism, depression, diabetes, heart disease, HIV/AIDS, influenza, and so many other causes of pain and suffering.

While the full impact of sequestration on biomedical research won’t be felt until next year or the following, reports are already starting to come in from the front lines. A new nationwide survey by the American Society for Clinical Oncology found that three out of four cancer researchers said the current federal funding situation is negatively affecting their ability to conduct research. The survey reports 28% of the cancer researchers have decided to participate in fewer federally-funded clinical trials; 27% have postponed the launch of a clinical trial; and 23% have had to limit patient enrollment on a clinical trial. These are very sobering statistics—especially for cancer patients and their loved ones.

Perhaps the most serious and long-lasting impact of sequestration on U.S. science is the one that is most difficult to measure. We fear this budget uncertainty is going to hit young researchers the hardest because a lack of funding leads to career uncertainty and could drive many of them out of the country or even out of science completely. This is our nation’s priceless pool of innovative talent—the source of the high-risk, high-reward research that may lead us to the next Nobel Prize or next big breakthrough in medical care. If our current budget battles cost the United States an entire generation of scientists, we will have compromised our nation’s global standing in biomedical research and slowed the improvement of health for all Americans.

This is a defining moment for the United States. As a nation, history will judge us by how we set priorities. Should not NIH-funded research aimed at alleviating suffering and advancing human health rank very high on that priority list? We hope that when everything is said and done, all of us can emerge telling the Tale of One Nation—a nation united in support of the value of biomedical research.

Note: Sally Rockey, Ph.D., is NIH’s Deputy Director for Extramural Research

Dear Bill Gates, and the billionaires out there, fill the the gap. Save our country. Pretty please.

Congress, shame on you!!!

Call me when any one of those countries catches up the US:

http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/GB.XPD.RSDV.GD.ZS/countries/1W-US-CN-DE-JP-KR-CA?display=graph

Credit to S. Korea and Japan for spending proportionately more, but a larger US GDP base still makes us the leader.

Did you ask yourself why is Congress cutting budgets? Maybe the public is unhappy with the productivity of the NIH funded research? Look at the end result of this research. No breakthrough new drugs. No new treatments. The NIH system is broken. Stop crying. Stop blaming others. Fix it.

Consider the following quote from a study conducted by Fabio Pammoll, Laura Magazzini and Massimo Riccaboni published in Nature Reviews: “. In other words, every year, the number of expected NMEs generated by the projects started between 2000–2004 is less than one-half of the number of expected NMEs per year generated by R&D projects started between 1990 and 1999.” This is the Productivity Crisis in Drug Discovery. The NIH funded research in not producing the expected results. No results. No funding.

Ran Ronen,

Clearly, because there are no new drugs or treatments that you can think of, no one in biomedical research is working on finding these. There are none in clinical trials, there are none in development, there are none being explored what-so-ever … None of the research into finding new drugs and treatments have advanced the field by disproving the leading theories or by finding portions of treatments that were beneficial. Obviously the best solution to a lack of new drugs and treatments is to cut funding for something that we desperately need to punish those lazy silly scientists who haven’t made a breakthrough yet. This way we’ll have fewer scientists funded to try to find new drugs and treatments. Surely, having fewer minds pursuing a problem that many minds have failed to solve will get us a solution faster! Pardon me, but I’d rather not cut off my nose to spite my face …

GaiasEyes,

Let me start by pointing to a great paper by Jack W. Scannell, Alex Blanckley, Helen Boldon and Brian Warrington.

“Over the past 60 years, there have been major advances in many of the scientific and technological inputs into drug research and development (R&D). … There have also been substantial efforts to understand and improve the management of the commercial R&D process. … However, in parallel — as many have discussed — R&D efficiency, measured

simply in terms of the number of new drugs brought to market by the global biotechnology and pharmaceutical industries per billion US dollars of R&D spending, has declined fairly steadily.”

What is the effect of this decline in productivity?

“Seeking such an explanation is important because Eroom’s Law (the authors name for the Productivity Crisis) — if it holds — has very unpleasant consequences. Indeed, financial markets already appear to believe in Eroom’s Law, or something similar to it, and the impact is being seen in cost-cutting measures implemented by major drug companies. … they have less reason to be biased towards optimism about the likelihood of Eroom’s Law being successfully counteracted than those who are working in the industry, or those who sell consulting services to the industry. Shareholders ultimately appoint executives and control resource allocation, so their perceptions matter. It is likely that Pfizer, Merck &Co., AstraZeneca and Eli Lilly will be spending less — in nominal terms — in 2015 than they did in 2011, partly in response to shareholder pressure.”

Now you see the same reaction by Congress. Shareholders are disappointed. The general public is frustrated. It is time for a change. The old system failed. No results, no funding. By the way, is this the basic principle of any R01? Show results and you get funding? Same holds for the entire NIH. Show results, get funding. No results. No funding.

I cannot help but think you are not in research based on your comments, or that you are not in academic research.

Allow me to define an R01 for you, as per the NIH website:

“The Research Project (R01) grant is an award made to support a discrete, specified, circumscribed project to be performed by the named investigator(s) in an area representing the investigator’s specific interest and competencies, based on the mission of the NIH.”

The goals of the NIH read, as per their mission statement:

“- to foster fundamental creative discoveries, innovative research strategies, and their applications as a basis for ultimately protecting and improving health;

– to develop, maintain, and renew scientific human and physical resources that will ensure the Nation’s capability to prevent disease;

– to expand the knowledge base in medical and associated sciences in order to enhance the Nation’s economic well-being and ensure a continued high return on the public investment in research; and

– to exemplify and promote the highest level of scientific integrity, public accountability, and social responsibility in the conduct of science.”

Allow me to draw your attention to a few key components of those two quotes. The R01 description is written in the future tense, it is an award to provide funds to pursuing the proposed project. It is not designed to be an award given for research that has already been completed. This is further demonstrated by the NIH mission statement to foster creative discoveries and research strategies (not reward them) and through this to expand the knowledge base. … R01’s are measured by the strength of preliminary data, the ability to test the presented hypothesis, and the significance of the reasonably anticipated results. What good is it to give researchers money for projects they have already completed and published? And, by the way, often times the quality of the researcher’s previous work and ability to deliver on previous grants does (whether intentionally or not) come in to consideration when R01’s are reviewed. The last decade and a half has seen a change in the funding of R01’s to go toward “safer” projects. We’ve observed that a good idea with preliminary data is insufficient now because researchers are waiting longer to submit R01’s on projects until they have far more than preliminary data. This is a reaction to the decrease in NIH budget, leading to a decrease in the percentage of applicants that receive funding. Perhaps that is the source of your misconception that R01’s are designed to be awarded after the research is completed. …

Now, I’m certain you’ll immediately alight on the portion of the mission statement that reads “enhance the Nation’s economic well-being and ensure a continued high return on the public investment in research”. You would probably argue that because you don’t see enough coming out of academic research we’re making a poor return on investment. That argument is short sighted and usually arises from a lack of understanding the inherent nature of research. I think many individuals forget (or don’t realize) that research is observational. We identify a question, formulate a hypothesis, design experiments to test the validity of the hypothesis and observe the results of the experiment to determine if the hypothesis is proven or disproven and move forward from there. Research cannot be proactive the way the general public thinks. We CAN identify that there is a need for new antibiotics against, say, staph but we cannot just run in to a lab and synthesize it. We have to identify aspects of staph that we can target to rid the body of the organism. Then you also have to consider what the side effects will be. … a lot of the drugs tested fail not because they are ineffective, not because we simply aren’t trying hard enough, but because these are extremely difficult problems to solve and questions to answer. Yet every one of the drugs that is tested, whether it makes it to the market or fails before reaching clinical trials, provides a new piece of information to the field … one more piece of information that moves us toward a better understanding of how to make an antibiotic that is safe and effective. It “expand[s] the knowledge base in medical and associated sciences…”.

As far as the general public’s frustration with science goes, I’m not sure what to do about that. I see article after article on news websites about the advances that medical research is making daily …

All this is not to say that the current system isn’t broken, but I think you and I will have very different opinions on what is broken and how to fix it.

My main point, clearly presented in my first comment, is the following: “Why is Congress cutting budgets?” … You try to convince me (and the public) that Congress should not cut the NIH budget by rehashing the same arguments the NIH used in the past. The public is aware of these arguments. These arguments are not new. And they don’t work anymore. Why not? What changed?

Think of the NIH as a company producing a product. Also think of the public and Congress as customers in the same market. As it turns out, Congress in not interested in the NIH product anymore. Congress is not willing to pay for this product. Why not? What product will Congress pay for?

I tried to answer this question in my previous comments. In contrast, your comments, and the original post by Dr. Sally Rockey and Dr. Francis Collins completely ignore this question. As any business owner will tell you, when you ignore your customer, you lose your business! Since the NIH ignores its customer, the NIH is losing its funding.

More specifically, you say that “The last decade and a half has seen a change in the funding of R01′s to go toward ‘safer’ projects.” But this method doesn’t work. “Safer” means marginal improvements to the current paradigm. But this paradigm failed. … Congress doesn’t want you to be safe. Congress wants you to produce results. And results mean better health. Congress is not expecting you to concentrate on advancing science. After all, you are the National Institute of Health. You are not the National Science Foundation.

You say that “You would probably argue that because you don’t see enough coming out of academic research we’re making a poor return on investment. That argument is short sighted.” Let us return to the Scannel, et al, paper. In Figure 1 they show that the overall decline in R&D deficiency started in 1950’s. Is waiting for 60 years regarded “short sighted”? How long is not “short sighted”?

Ran,

I think your comments are fine and bring up some bold topics that should be talked about, although I think NIH leadership is quite aware that bringing new treatments to public funders is a priority–I mean, NCATS [the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences] was just created.

However, I think you need to look past therapeutics (maybe you are, but it’s not clear). We have a menu of cutting-edge imaging tests right now that have NIH roots. In fact, CMS [Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services] just DENIED coverage for amyloid imaging (supported by NIH researchers for years and years), when it is a proven combinatorial marker for AD [Alzheimer’s disease]. Any outrage over for the payers for blocking public access to a publicly-funded Dx [diagnostics]? In short, we have a ton of new diagnostics brought to market from NIH research that greatly benefit patients. Therapeutics is just one piece of the portfolio and generally take longer.

To get to your main point though, the rationale that “Congress wants results and is cutting funding because there are not enough new products” is not really accurate. There are folks in Congress right now that want to cut government–all of it. Indiscriminately. They have shown no national interest in NIH’s role in medical discovery, mainly because it’s not done it their districts. That is short-sighted. The public as a whole benefits from medical innovations. So, to bring it back to the imaging example above: when the patient in rural Idaho pays OOP [out-of-pocket] to get an NIH-created PET scan for beta-amyloid (and writes their Congressman for CMS coverage), I hope those same small-government Representatives remember to thank NIH for providing the new test and giving their constituent the option for a firm diagnosis.