Antibiotic Compound Kills Hard-to-Treat, Infectious Bacteria While Sparing Healthy Bacteria in the Gut

Posted on by Dr. Monica M. Bertagnolli

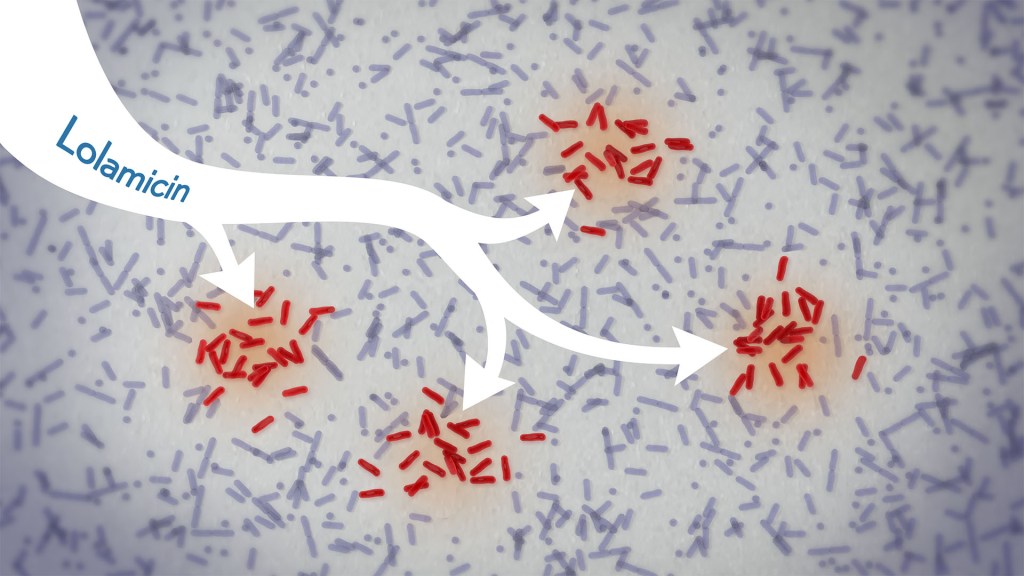

In a new study, an antibiotic compound, lolamicin, targeted infectious, gram-negative bacteria without harming the gut microbiome. Credit: Donny Bliss/NIH

Drug-resistant bacteria are responsible for a rise in serious, hospital-acquired infections, including pneumonia and sepsis. Many of these bacteria are classified as “gram-negative,” and are harder to kill than “gram-positive” bacteria. Unfortunately, the limited number of antibiotics that can help combat these dangerous infections can also damage healthy microbes in the gut, leaving people at risk for other, potentially life-threatening infections. Such antibiotic-induced disruption has also been linked in studies to irritable bowel syndrome, colon cancer, and many other health conditions.

There’s a great need for more targeted antibiotics capable of fending off infectious gram-negative bacteria while sparing the community of microbes in the gut, collectively known as the gut microbiome. Now, in findings reported in the journal Nature, a research team has demonstrated a promising candidate for the job. While the antibiotic hasn’t yet been tested in people, the findings in cell cultures suggest it could work against more than 130 drug-resistant bacterial strains. What’s more, the study, supported in part by NIH, shows that this compound, when given to infected mice, thwarts potentially life-threatening bacteria while leaving the animals’ gut microbiomes intact.

One reason it’s been difficult to find antibiotics that work against gram-negative bacteria without killing too many benign bacteria is that most promising targets for gram-negative bacteria are shared by gram-positive bacteria. But the team, led by Paul Hergenrother and Kristen Muñoz at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, recognized an intriguing target for more specific microbiome-sparing antibiotics in a collection of proteins that gram-negative bacteria depend on to transport lipoproteins between their inner and outer cell membranes. Gram-positive bacteria, with only one cell membrane, don’t require lipoprotein transport and therefore lack these proteins.

The researchers knew that this lipoprotein-transport system, known as the Lol system, is required for infectious E. coli bacteria to live and grow. It’s also found in many other infectious gram-negative bacteria. They thought that compounds aimed at this system might be doubly selective—specifically targeting hard-to-treat gram-negative bacteria and leaving the gut microbiome relatively unscathed. They also knew other drugs targeting the Lol system had showed some promise in selectively targeting gram-negative bacteria. However, these antibiotics didn’t work well enough on their own to fight infections.

In the new study, the researchers tinkered with the design of those compounds in search of one that might work better. It led them to a compound, which they call lolamicin, that they found could selectively target three different types of infectious gram-negative bacteria (E. coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Enterobacter cloacae) in the lab. They also found that the antibiotic at high doses killed up to 90% of multidrug-resistant strains of those infectious bacteria in cell cultures.

In additional experiments, the researchers wanted to see how well lolamicin would treat infected mice. They found that treatment with the antibiotic was well tolerated by the animals. They went on to show in mouse models of acute pneumonia and sepsis that oral treatment with lolamicin reduced the number of infectious bacteria. When mice with sepsis were treated with lolamicin, all of them survived. Lolamicin treatment also rescued 70% of mice with pneumonia infection.

While treatment with amoxicillin, a broad-spectrum antibiotic, and clindamycin, an antibiotic that only targets gram-positive bacteria, disrupted the assemblage of healthy microbes living in the mouse gut, the researchers found that treatment with lolamicin did not. They saw no big changes in the microbial community present in the mouse gut after three days of lolamicin treatment. As a result, unlike mice treated with the other two antibiotics, mice treated with lolamicin were protected from secondary infection by Clostridioides difficile, a bacterium that can infect the colon to cause diarrhea and life-threatening tissue damage.

These new findings, while promising, are at an early stage of drug discovery and development, and much more study is needed before this compound could be tested in people. It will also be important to learn how rapidly infectious gram-negative bacteria may develop resistance to lolamicin. Nevertheless, these findings suggest it may be possible to further develop lolamicin or related antibiotic compounds targeting the Lol system to treat dangerous gram-negative infections without harming the microbiome.

Reference:

Muñoz KA, et al. A Gram-negative-selective antibiotic that spares the gut microbiome. Nature. DOI: 10.1038/s41586-024-07502-0 (2024).

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases