tissue engineering

Regenerative Medicine: New Clue from Fish about Healing Spinal Cord Injuries

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

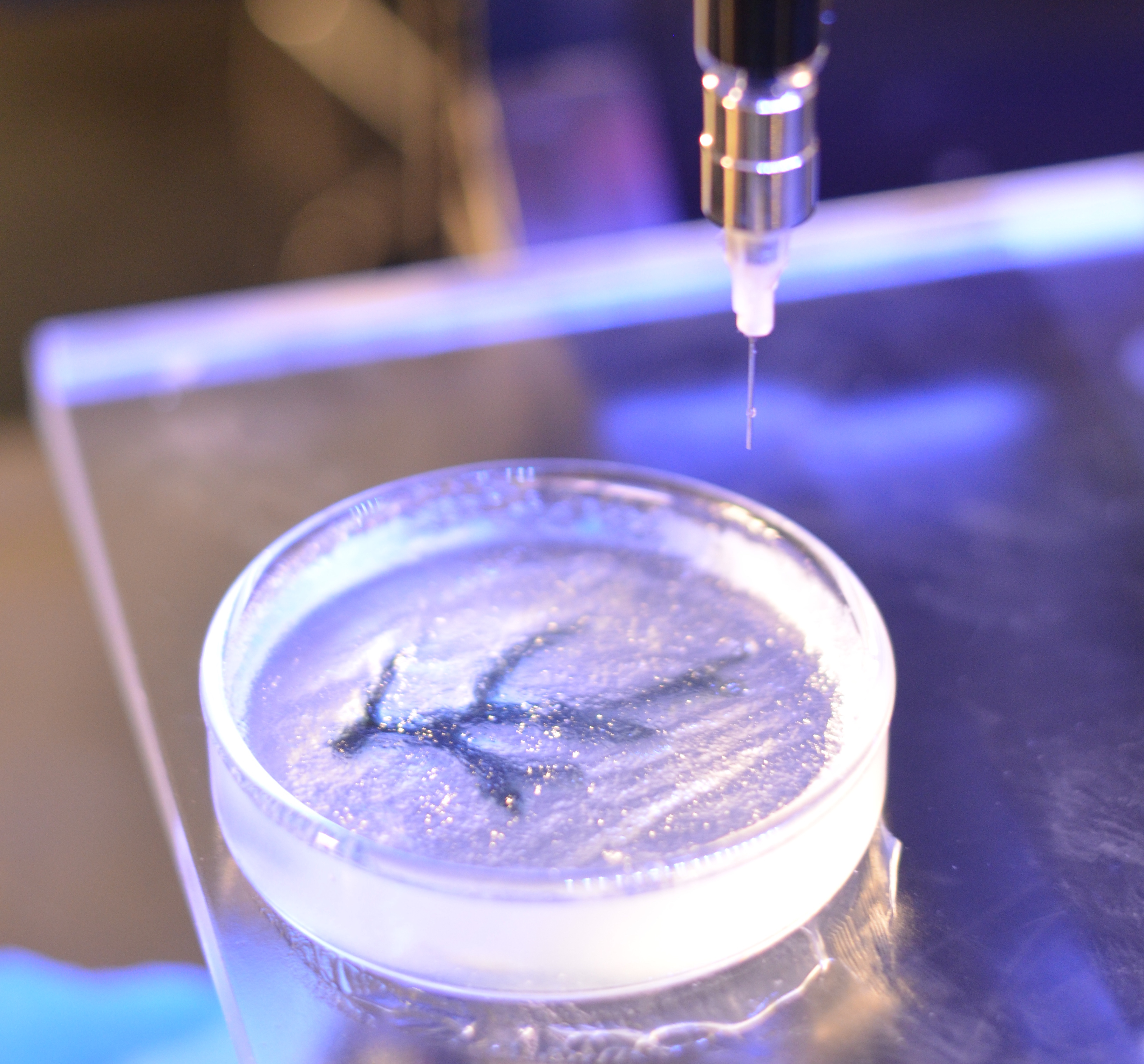

Caption: Tissue section of zebrafish spinal cord regenerating after injury. Glial cells (red) cross the gap between the severed ends first. Neuronal cells (green) soon follow. Cell nuclei are stained blue and purple.

Credit: Mayssa Mokalled and Kenneth Poss, Duke University, Durham, NC

Certain organisms have remarkable abilities to achieve self-healing, and a fascinating example is the zebrafish (Danio rerio), a species of tropical freshwater fish that’s an increasingly popular model organism for biological research. When the fish’s spinal cord is severed, something remarkable happens that doesn’t occur in humans: supportive cells in the nervous system bridge the gap, allowing new nerve tissue to restore the spinal cord to full function within weeks.

Pretty incredible, but how does this occur? NIH-funded researchers have just found an important clue. They’ve discovered that the zebrafish’s damaged cells secrete a molecule known as connective tissue growth factor a (CTGFa) that is essential in regenerating its severed spinal cord. What’s particularly encouraging to those looking for ways to help the 12,000 Americans who suffer spinal cord injuries each year is that humans also produce a form of CTGF. In fact, the researchers found that applying human CTGF near the injured site even accelerated the regenerative process in zebrafish. While this growth factor by itself is unlikely to produce significant spinal cord regeneration in human patients, the findings do offer a promising lead for researchers pursuing the next generation of regenerative therapies.

Stem Cell Research: New Recipes for Regenerative Medicine

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

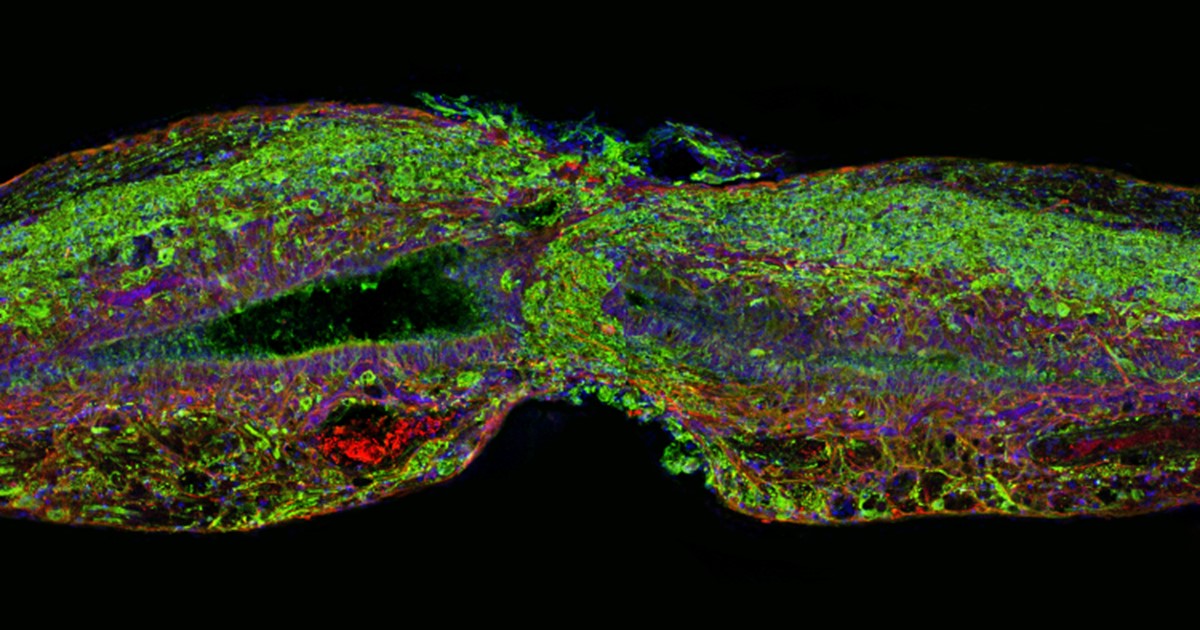

Caption: From stem cells to bone. Human bone cell progenitors, derived from stem cells, were injected under the skin of mice and formed mineralized structures containing cartilage (1-2) and bone (3).

Credit: Loh KM and Chen A et al., 2016

To help people suffering from a wide array of injuries and degenerative diseases, scientists and bioengineers have long dreamed of creating new joints and organs using human stem cells. A major hurdle on the path to achieving this dream has been finding ways to steer stem cells into differentiating into all of the various types of cells needed to build these replacement parts in a fast, efficient manner.

Now, an NIH-funded team of researchers has reported important progress on this front. The researchers have identified for the first time the precise biochemical signals needed to spur human embryonic stem cells to produce 12 key types of cells, and to do so rapidly. With these biochemical “recipes” in hand, researchers say they should be able to generate pure populations of replacement cells in a matter of days, rather than the weeks or even months it currently takes. In fact, they have already demonstrated that their high-efficiency approach can be used to produce potentially therapeutic amounts of human bone, cartilage, and heart tissue within a very short time frame.

LabTV: Curious about Post-Traumatic Osteoarthritis

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

If you like sports and you like science, I think you’ll enjoy meeting Avery White, an undergraduate studying biomedical engineering at the University of Delaware in Newark. In this LabTV profile, we catch up with White as she conducts basic research that may help us better understand—and possibly prevent—the painful osteoarthritis that often pops up years after knee injuries from sports and other activities.

Many athletes, along with lots of regular folks, are familiar with the immediate and painful consequences of tearing the knee’s cartilage (meniscus) or anterior cruciate ligament (ACL). Most also know that such injuries can usually be repaired by surgery. Yet, many people aren’t aware of the longer-term health threat posed by ACL and meniscus tears: a substantially increased risk of developing osteoarthritis years down the road—in some individuals, even as early as age 30. While treatments are available for such post-traumatic osteoarthritis, including physical therapy, pain medications, and even knee-replacement surgery, more preventive options are needed to avoid these chronic joint problems.

White’s interest in this problem is personal. She’s a volleyball player herself, her sister tore her ACL, and her mother damaged her meniscus. After spending a summer working in a lab, this Wilmington, DE native has grown increasingly interested in the field of tissue engineering. She says it offers her an opportunity to use “micro” cell biology techniques to address a “macro” challenge: finding ways to encourage the body to generate healthy new cells that may prevent or reverse injury-induced osteoarthritis.

What’s up next for White? She says maybe a summer internship in a lab overseas, and, on the more distant horizon, graduate school with the goal of earning a Ph.D.

Links:

University of Delaware Biomedical Engineering

Science Careers (National Institute of General Medical Sciences/NIH)

Careers Blog (Office of Intramural Training/NIH)

Reprograming Adult Cells to Produce Blood Vessels

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: New network of blood vessels (green) grown from reprogrammed adult human cells (blue: connective tissue, red: red blood cells)

Credit: Reproduced from R. Samuel et al, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:12774-9.

Individuals with heart disease, diabetes, and non-healing ulcers (which can lead to amputation) could all benefit greatly from new blood vessels to replace those that are diseased, damaged, or blocked. But engineering new blood vessels hasn’t yet been possible. Although we’ve learned how to reprogram human skin cells or white blood cells into so-called induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells—which have the potential to develop into different cell types—we haven’t really had the right recipe to nudge those cells down a path toward blood vessel development.

But now NIH-funded researchers at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston have taken another step in that direction.

Previous Page