pregnancy

Largest Study Yet Shows Mother’s Smoking Changes Baby’s Epigenome

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: Daniel Berehulak/Getty Images

Despite years of public health campaigns warning of the dangers of smoking when pregnant, many women are unaware of the risk or find themselves unable to quit. As a result, far too many babies are still being exposed in the womb to toxins that enter their mothers’ bloodstreams when they inhale cigarette smoke. Among the many infant and child health problems that have been linked to maternal smoking are premature birth, low birth weight, asthma, reduced lung function, sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), and cleft lip and/or palate.

Now, a large international study involving NIH-supported researchers provides a biological mechanism that may explain how exposure to cigarette toxins during fetal development can produce these health problems [1]. That evidence centers on the impact of the toxins on the epigenome of the infant’s body tissues. The epigenome refers to chemical modifications of DNA (particularly methylation of cytosines), as well as proteins that bind to DNA and affect its function. The genome of an individual is the same in all cells of their body, but the epigenome determines whether genes are turned on or off in particular cells. The study found significant differences between the epigenetic patterns of babies born to women who smoked during pregnancy and those born to non-smokers, with many of the differences affecting genes known to play key roles in the development of the lungs, face, and nervous system.

Zika and Birth Defects: The Evidence Mounts

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: Human neural progenitor cells (gray) infected with Zika virus (green) increased the enzyme caspase-3 (red), suggesting increased cell death.

Credit: Sarah C. Ogden, Florida State University, Tallahassee

Recently, public health officials have raised major concerns over the disturbing spread of the mosquito-borne Zika virus among people living in and traveling to many parts of Central and South America [1]. While the symptoms of Zika infection are typically mild, grave concerns have arisen about its potential impact during pregnancy. The concerns stem from the unusual number of births of children with microcephaly, a very serious condition characterized by a small head and damaged brain, coinciding with the spread of Zika virus. Now, two new studies strengthen the connection between Zika and an array of birth defects, including, but not limited to, microcephaly.

In the first study, NIH-funded laboratory researchers show that Zika virus can infect and kill human neural progenitor cells [2]. Those progenitor cells give rise to the cerebral cortex, a portion of the brain often affected in children with microcephaly. The second study, involving a small cohort of women diagnosed with Zika virus during their pregnancies in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, suggests that the attack rate is disturbingly high, and microcephaly is just one of many risks to the developing fetus. [3]

Human Folate Receptor Model May Aid Antifolate Drug Design

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

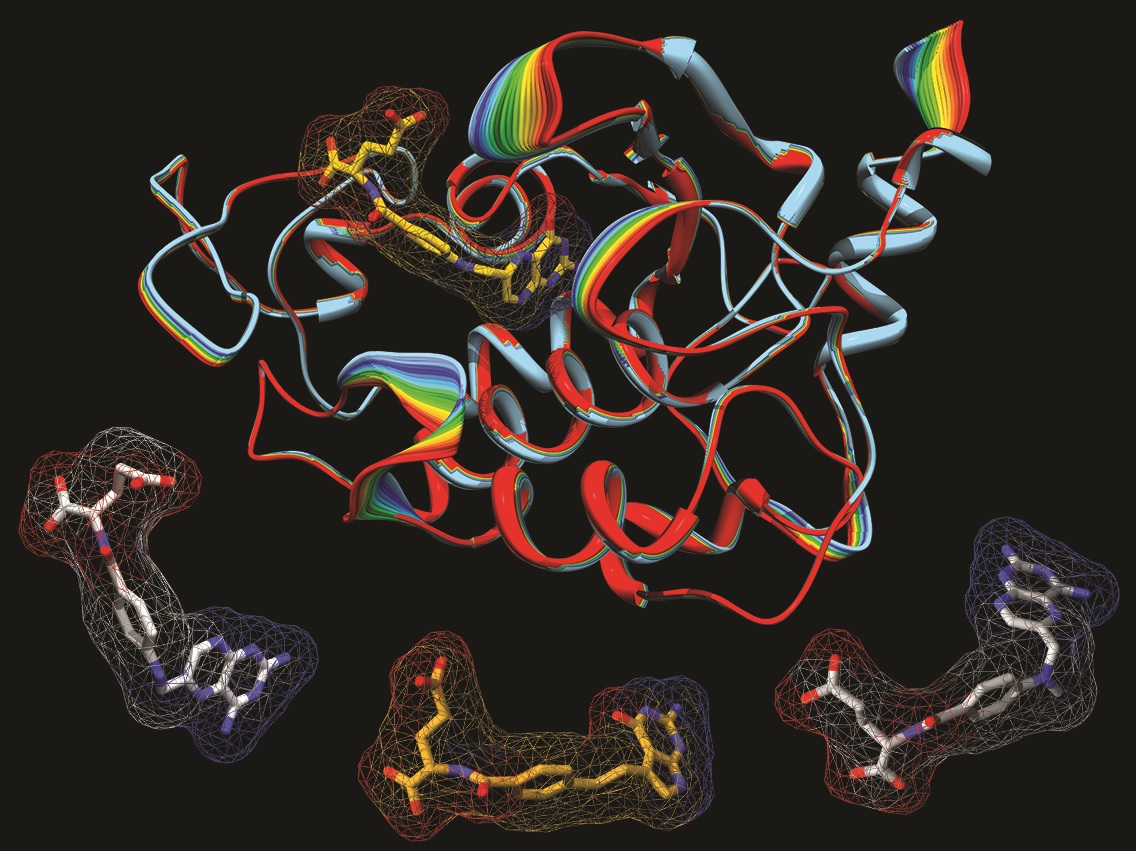

Caption: A model of the human folate receptor (top) and three antifolate drugs used in chemotherapy: aminopterin (left), pemetrexed, and methotrexate (right).

Credit: Charles Dann III / Courtesy of Indiana University

Vitamin B9 or folic acid, which is found in dark green leafy vegetables, is essential for cells to grow and divide rapidly—as they do in a growing embryo. This is why women are advised to take folic acid supplements before conception and during pregnancy: inadequate folate raises the risk of brain and spinal cord defects. But while folic acid is key to normal cell growth, rapidly dividing cancer cells also have a tremendous appetite for this vitamin.

Drugs called antifolates have been used for decades in chemotherapy to starve cancer cells of folate, which can help kill the tumor. These drugs have also been used to treat inflammatory diseases like rheumatoid arthritis and Crohn’s disease. But many of these drugs have nasty side effects because they also enter normal healthy cells, depriving them of this essential compound.

Previous Page