Parkinson’s disease

Teaching Computers to “See” the Invisible in Living Cells

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: Steven Finkbeiner, University of California, San Francisco and the Gladstone Institutes

For centuries, scientists have trained themselves to look through microscopes and carefully study their structural and molecular features. But those long hours bent over a microscope poring over microscopic images could be less necessary in the years ahead. The job of analyzing cellular features could one day belong to specially trained computers.

In a new study published in the journal Cell, researchers trained computers by feeding them paired sets of fluorescently labeled and unlabeled images of brain tissue millions of times in a row [1]. This allowed the computers to discern patterns in the images, form rules, and apply them to viewing future images. Using this so-called deep learning approach, the researchers demonstrated that the computers not only learned to recognize individual cells, they also developed an almost superhuman ability to identify the cell type and whether a cell was alive or dead. Even more remarkable, the trained computers made all those calls without any need for harsh chemical labels, including fluorescent dyes or stains, which researchers normally require to study cells. In other words, the computers learned to “see” the invisible!

Wearable Scanner Tracks Brain Activity While Body Moves

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: Wellcome Centre for Human Neuroimaging, University College London.

In recent years, researchers fueled by the BRAIN Initiative and many other NIH-supported efforts have made remarkable progress in mapping the human brain in all its amazing complexity. Now, a powerful new imaging technology promises to further transform our understanding [1]. This wearable scanner, for the first time, enables researchers to track neural activity in people in real-time as they do ordinary things—be it drinking tea, typing on a keyboard, talking to a friend, or even playing paddle ball.

This new so-called magnetoencephalography (MEG) brain scanner, which looks like a futuristic cross between a helmet and a hockey mask, is equipped with specialized “quantum” sensors. When placed directly on the scalp surface, these new MEG scanners can detect weak magnetic fields generated by electrical activity in the brain. While current brain scanners weigh in at nearly 1,000 pounds and require people to come to a special facility and remain absolutely still, the new system weighs less than 2 pounds and is capable of generating 3D images even when a person is making motions.

Snapshots of Life: The Birth of New Neurons

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

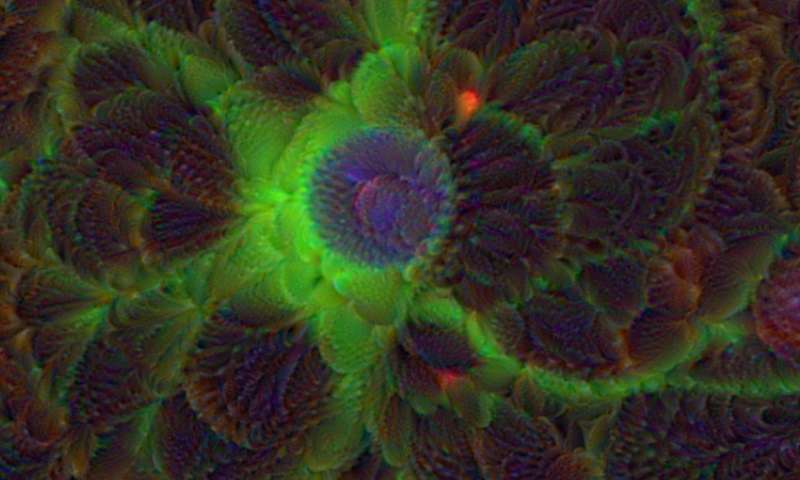

After a challenging day at work or school, sometimes it may seem like you are down to your last brain cell. But have no fear—in actuality, the brains of humans and other mammals have the potential to produce new neurons throughout life. This remarkable ability is due to a specific type of cell—adult neural stem cells—so beautifully highlighted in this award-winning micrograph.

Here you see the nuclei (purple) and arm-like extensions (green) of neural stem cells, along with nuclei of other cells (blue), in brain tissue from a mature mouse. The sample was taken from the subgranular zone of the hippocampus, a region of the brain associated with learning and memory. This zone is also one of the few areas in the adult brain where stem cells are known to reside.

New Imaging Approach Reveals Lymph System in Brain

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Considering all the recent advances in mapping the complex circuitry of the human brain, you’d think we’d know all there is to know about the brain’s basic anatomy. That’s what makes the finding that I’m about to share with you so remarkable. Contrary to what I learned in medical school, the body’s lymphatic system extends to the brain—a discovery that could revolutionize our understanding of many brain disorders, from Alzheimer’s disease to multiple sclerosis (MS).

Researchers from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), the National Cancer Institute (NCI), and the University of Virginia, Charlottesville made this discovery by using a special MRI technique to scan the brains of healthy human volunteers [1]. As you see in this 3D video created from scans of a 47-year-old woman, the brain—just like the neck, chest, limbs, and other parts of the body—possesses a network of lymphatic vessels (green) that serves as a highway to circulate key immune cells and return metabolic waste products to the bloodstream.

Snapshots of Life: Making the Brain Transparent

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: Ken Chan and Viviana Gradinaru Group, Caltech

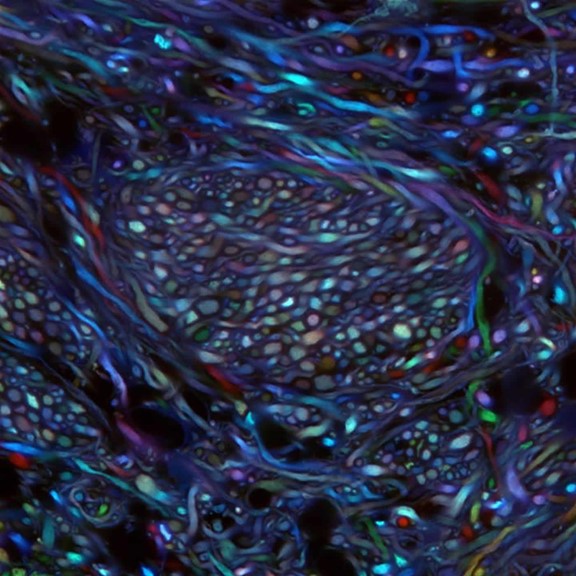

What you are looking at above is something scientists couldn’t even dream of imaging less than a decade ago: bundles of neurons in the brainstem of an adult mouse. These bundles are randomly labeled with various colors that enable researchers to trace the course of each as it projects from the brainstem areas to other parts of the brain. Until recently, such a view would have been impossible because, like other organs, the brain is opaque and had to be sliced into thin, transparent sections of tissue to be examined under a light microscope. These sections forced a complex 3D structure to be visualized in 2D, losing critical detail about the connections.

But now, researchers have developed innovative approaches to make organs and other large volumes of tissue transparent when viewed with standard light microscopy [1]. This particular image was made using the Passive CLARITY Technique, or PACT, developed by the NIH-supported lab of Viviana Gradinaru at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), Pasadena. Gradinaru has been working on turning tissues transparent since 2010, starting as a graduate student in the lab of CLARITY developer and bioengineering pioneer Karl Deisseroth at Stanford University. PACT is her latest refinement of the concept.

LabTV: Curious About Parkinson’s Disease

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

When the young scientist featured in this LabTV video first learned about induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells a few years ago as an undergrad, he thought it would be cool if he could someday work with this innovative technology. Today, as a graduate student, Kinsley Belle is part of a research team that’s using iPS cells on a routine basis to gain a deeper understanding of Parkinson’s disease.

Derived from genetically reprogrammed skin cells or white blood cells, iPS cells have the potential to develop into many different types of cells, providing scientists with a powerful tool to model a wide variety of diseases in laboratory dishes. At the University of Miami’s John P. Hussman Institute for Human Genomics, Belle and his colleagues are taking advantage of an iPS model of Parkinson’s disease to explore its molecular roots. Their goal? To use that information to develop better treatments or maybe even a cure for the neurodegenerative disorder that affects at least a half-million Americans.

siRNAs: Small Molecules that Pack a Big Punch

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: Richard J. Youle Laboratory, NINDS, NIH

It would be terrific if we could turn off human genes in the laboratory, one at a time, to figure out their exact functions and learn more about how our health is affected when those functions are disrupted. Today, I’m excited to announce the availability of new data that will empower researchers to do just that on a genome-wide scale. As part of a public-private collaboration between the NIH’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) and Life Technologies Corporation, researchers now have access to a wealth of information about small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), which are snippets of ribonucleic acid (RNA) with the power to turn off a gene, or reduce its activity—in much the same way that we use a dimmer switch to modulate a light.

Yeast Reveals New Drug Target for Parkinson’s

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: Daniel Tardiff, Whitehead Institute

Many progressive neurodegenerative disorders like Alzheimer’s, Huntington’s, and Parkinson’s disease, are characterized by abnormal clumps of proteins that clog up the cell and disrupt normal cellular functions. But it’s difficult to study these complex disease processes directly in the brain—so NIH-funded researchers, led by a team at the Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research, Cambridge, MA, have turned to yeast for help.

Now, it may sound odd to study a brain disease in yeast, a microorganism long used in baking and brewing. After all, the brain is made up of billions of cells of many different types, while yeast grows as a single cell. But because the processes of protein production are generally conserved from yeast to humans, we can use this infinitely simpler organism to figure out what the proteins clumps are doing and test various drug candidates to halt the damage.

New Insight into Parkinson’s Disease

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: Samantha Orenstein and Dr. Esperanza Arias, Department of Developmental and Molecular Biology, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, New York

I’m blogging today to tell you about a new NIH funded report [1] describing a possible cause of Parkinson’s disease: a clog in the protein disposal system.

You probably already know something about Parkinson’s disease. Many of us know individuals who have been stricken, and actor Michael J. Fox, who suffers from it, has done a great job talking about and spreading awareness of it. Parkinson’s is a progressive neurodegenerative condition in which the dopamine-producing cells in the brain region called the substantia nigra begin to sicken and die. These cells are critical for controlling movement; their death causes shaking, difficulty moving, and the characteristic slow gait. Patients can have trouble swallowing, chewing, and speaking. As the disease progresses, cognitive and behavioral problems take hold—depression, personality shifts, sleep disturbances.

Previous Page