muscle

Sharing a Story of Hope

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Whether by snail mail, email, or social media, it’s the time of year for catching up with family and friends. As NIH Director, I’m also fortunate to hear from some of the amazing people who’ve been helped by NIH research. Among the greetings to arrive in my inbox this holiday season is this incredible video from a 15-year-old named Aaron, who is fortunate enough to count two states—Alabama and Colorado—as his home.

As a young boy, Aaron was naturally athletic, speeding around the baseball diamond and competing on the ski slopes in freestyle mogul. But around the age of 10, Aaron noticed something strange. He couldn’t move as fast as usual. Aaron pushed himself to get back up to speed, but his muscles grew progressively weaker.

Snapshots of Life: Muscling in on Development

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Twice a week, I do an hour of weight training to maintain muscle strength and tone. Millions of Americans do the same, and there’s always a lot of attention paid to those upper arm muscles—the biceps and triceps. Less appreciated is another arm muscle that pumps right along during workouts: the brachialis. This muscle—located under the biceps—helps your elbow flex when you are doing all kinds of things, whether curling a 50-pound barbell or just grabbing a bag of groceries or your luggage out of the car.

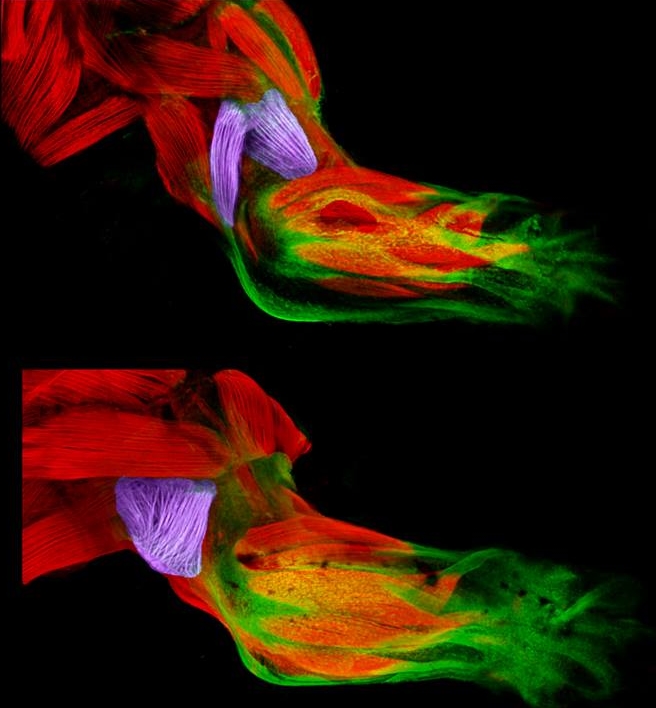

Now, scientific studies of the triceps and brachialis are providing important clues about how the body’s 40 different types of limb muscles assume their distinct identities during development [1]. In these images from the NIH-supported lab of Gabrielle Kardon at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, you see the developing forelimb of a healthy mouse strain (top) compared to that of a mutant mouse strain with a stiff, abnormal gait (bottom).

Snapshots of Life: Picturing the Developing Windpipe

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

The image above shows a small section of the trachea, or windpipe, of a developing mouse. Although it’s only about the diameter of a pinhead at this stage of development, the mouse trachea has a lot in common structurally with the much wider and longer human trachea. Both develop from a precisely engineered balance between the flexibility of smooth muscle and the supportive strength and durability of cartilage.

Here you can catch a glimpse of this balance. C-rings of cartilage (red) wrap around the back of the trachea, providing the support needed to keep its tube open during breathing. Attached to the ends of the rings are dark shadowy bands of smooth muscles, which are connected to a web of nerves (green). The tension supplied by the muscle cells is essential for proper development of those neatly organized cartilage rings.

Snapshots of Life: An Elegant Design

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: David Sleboda and Thomas Roberts, Brown University, Providence, RI

Over the past few years, my blog has highlighted winners from the annual BioArt contest sponsored by the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology (FASEB). So, let’s keep a good thing going with one of the amazing scientific images that captured top honors in FASEB’s latest competition: a scanning electron micrograph of the hamstring muscle of a bullfrog.

That’s right, a bullfrog, For decades, researchers have used the American bullfrog, Rana catesbeiana, as a model for studying the physiology and biomechanics of skeletal muscles. My own early work with electron microscopy, as a student at Yale in the 1970s, was devoted to producing images from this very tissue. Thanks to its disproportionately large skeletal muscles, this common amphibian has played a critical role in helping to build the knowledge base for understanding how these muscles work in other organisms, including humans.

Revealed in this picture is the intricate matrix of connective tissue that holds together the frog’s hamstring muscle, with the muscle fibers themselves having been digested away with chemicals. And running diagonally, from lower left to upper right, you can see a band of fibrils made up of a key structural protein called collagen.

Creative Minds: The Muscle-Brain Connection

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

There’s mounting evidence that exercise has a powerful effect on the human brain. For example, many studies have shown that physical activity appears to reduce the incidence of depression. Exercise can also delay or possibly even prevent Alzheimer’s disease, as well as easing symptoms in people who have these disorders [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]. But how, exactly, does getting our legs moving and our hearts pumping exert a positive influence on our brains?

Two scientists at Stanford University School of Medicine are out to get some answers to this important question. They have proposed that when we exercise, our muscles secrete a factor or combination of factors into the bloodstream, leading to structural and functional changes in the brain.

The Beauty of Smooth Muscle

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

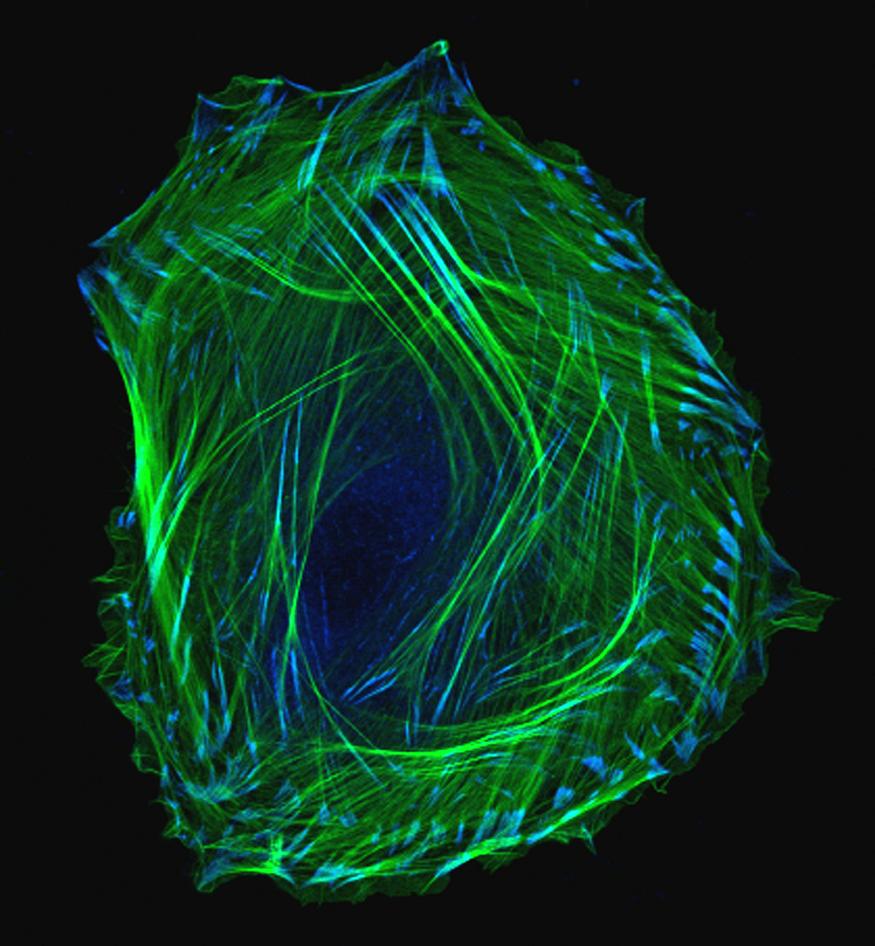

We humans have long wondered how, exactly, we develop from embryos into adults. This photo of an embryonic smooth muscle cell hints at the tremendous complexity of this fundamental biological mystery. And for those of you who might be wondering just what smooth muscles are, they’re the involuntary muscles found in places like the walls of our blood vessels, the digestive tract, the bladder, and the respiratory system.

This exquisite photo was produced using laser scanning confocal microscopy — a precise imaging method that includes the dimension of depth for scientific analysis. Here, green is used to label thin filaments of the protein actin, which is a key component of the cell’s cytoskeleton, and blue indicates another protein, called vinculin, which is enriched in locations involved in cell-cell adhesion.

Slowly but surely, using all the technology and tools available to us, we are unraveling the mysteries of biology — and turning our discoveries into health.

Previous Page