epilepsy

Brain Imaging: Advance Aims for Epilepsy’s Hidden Hot Spots

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

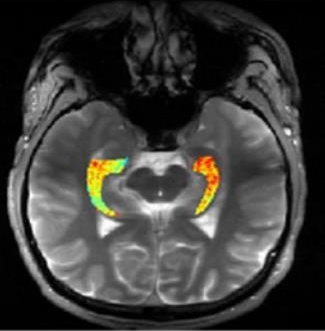

Credit: Reddy Lab, University of Pennsylvania

For many of the 65 million people around the world with epilepsy, modern medications are able to keep the seizures under control. When medications fail, as they do in about one-third of people with epilepsy, surgery to remove affected brain tissue without compromising function is a drastic step, but offers a potential cure. Unfortunately, not all drug-resistant patients are good candidates for such surgery for a simple reason: their brains appear normal on traditional MRI scans, making it impossible to locate precisely the source(s) of the seizures.

Now, in a small study published in Science Translational Medicine [1], NIH-funded researchers report progress towards helping such people. Using a new MRI method, called GluCEST, that detects concentrations of the nerve-signaling chemical glutamate in brain tissue [2], researchers successfully pinpointed seizure-causing areas of the brain in four of four volunteers with drug-resistant epilepsy and normal traditional MRI scans. While the findings are preliminary and must be confirmed by larger studies, researchers are hopeful that GluCEST, which takes about 30 minutes, may open the door to new ways of treating this type of epilepsy.

Epilepsy Research Benefits from the Crowd

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

For millions of people with epilepsy, life comes with too many restrictions. If they just had a reliable way to predict when their next seizure will come, they could have a chance at leading more independent and productive lives.

For millions of people with epilepsy, life comes with too many restrictions. If they just had a reliable way to predict when their next seizure will come, they could have a chance at leading more independent and productive lives.

That’s why it is so encouraging to hear that researchers have developed a new algorithm that can predict the onset of a seizure correctly 82 percent of the time. Until recently, the best algorithm was hardly better than flipping a coin, leading some to speculate that seizures are random neurological events that can’t be predicted at all. But the latest leap forward shows that seizures certainly can be predicted, and our research efforts are headed in the right direction to make them even more predictable. The other big news is how this new algorithm was developed: it’s the product of a crowdsourcing competition.

Previous Page