coronavirus

mRNA Vaccines May Pack More Persistent Punch Against COVID-19 Than Thought

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Many people, including me, have experienced a sense of gratitude and relief after receiving the new COVID-19 mRNA vaccines. But all of us are also wondering how long the vaccines will remain protective against SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus responsible for COVID-19.

Earlier this year, clinical trials of the Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech vaccines indicated that both immunizations appeared to protect for at least six months. Now, a study in the journal Nature provides some hopeful news that these mRNA vaccines may be protective even longer [1].

In the new study, researchers monitored key immune cells in the lymph nodes of a group of people who received both doses of the Pfizer-BioNTech mRNA vaccine. The work consistently found hallmarks of a strong, persistent immune response against SARS-CoV-2 that could be protective for years to come.

Though more research is needed, the findings add evidence that people who received mRNA COVID-19 vaccines may not need an additional “booster” shot for quite some time, unless SARS-CoV-2 evolves into new forms, or variants, that can evade this vaccine-induced immunity. That’s why it remains so critical that more Americans get vaccinated not only to protect themselves and their loved ones, but to help stop the virus’s spread in their communities and thereby reduce its ability to mutate.

The new study was conducted by an NIH-supported research team led by Jackson Turner, Jane O’Halloran, Rachel Presti, and Ali Ellebedy at Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis. That work builds upon the group’s previous findings that people who survived COVID-19 had immune cells residing in their bone marrow for at least eight months after the infection that could recognize SARS-CoV-2 [2]. The researchers wanted to see if similar, persistent immunity existed in people who hadn’t come down with COVID-19 but who were immunized with an mRNA vaccine.

To find out, Ellebedy and team recruited 14 healthy adults who were scheduled to receive both doses of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine. Three weeks after their first dose of vaccine, the volunteers underwent a lymph node biopsy, primarily from nodes in the armpit. Similar biopsies were repeated at four, five, seven, and 15 weeks after the first vaccine dose.

The lymph nodes are where the human immune system establishes so-called germinal centers, which function as “training camps” that teach immature immune cells to recognize new disease threats and attack them with acquired efficiency. In this case, the “threat” is the spike protein of SARS-COV-2 encoded by the vaccine.

By the 15-week mark, all of the participants sampled continued to have active germinal centers in their lymph nodes. These centers produced an army of cells trained to remember the spike protein, along with other types of cells, including antibody-producing plasmablasts, that were locked and loaded to neutralize this key protein. In fact, Ellebedy noted that even after the study ended at 15 weeks, he and his team continued to find no signs of germinal center activity slowing down in the lymph nodes of the vaccinated volunteers.

Ellebedy said the immune response observed in his team’s study appears so robust and persistent that he thinks that it could last for years. The researcher based his assessment on the fact that germinal center reactions that persist for several months or longer usually indicate an extremely vigorous immune response that culminates in the production of large numbers of long-lasting immune cells, called memory B cells. Some memory B cells can survive for years or even decades, which gives them the capacity to respond multiple times to the same infectious agent.

This study raises some really important issues for which we still don’t have complete answers: What is the most reliable correlate of immunity from COVID-19 vaccines? Are circulating spike protein antibodies (the easiest to measure) the best indicator? Do we need to know what’s happening in the lymph nodes? What about the T cells that are responsible for cell-mediated immunity?

If you follow the news, you may have seen a bit of a dust-up in the last week on this topic. Pfizer announced the need for a booster shot has become more apparent, based on serum antibodies. Meanwhile, the Food and Drug Administration and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said such a conclusion would be premature, since vaccine protection looks really good right now, including for the delta variant that has all of us concerned.

We’ve still got a lot more to learn about the immunity generated by the mRNA vaccines. But this study—one of the first in humans to provide direct evidence of germinal center activity after mRNA vaccination—is a good place to continue the discussion.

References:

[1] SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines induce persistent human germinal centre responses. Turner JS, O’Halloran JA, Kalaidina E, Kim W, Schmitz AJ, Zhou JQ, Lei T, Thapa M, Chen RE, Case JB, Amanat F, Rauseo AM, Haile A, Xie X, Klebert MK, Suessen T, Middleton WD, Shi PY, Krammer F, Teefey SA, Diamond MS, Presti RM, Ellebedy AH. Nature. 2021 Jun 28. [Online ahead of print]

[2] SARS-CoV-2 infection induces long-lived bone marrow plasma cells in humans. Turner JS, Kim W, Kalaidina E, Goss CW, Rauseo AM, Schmitz AJ, Hansen L, Haile A, Klebert MK, Pusic I, O’Halloran JA, Presti RM, Ellebedy AH. Nature. 2021 May 24. [Online ahead of print]

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Ellebedy Lab (Washington University, St. Louis)

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences

How Immunity Generated from COVID-19 Vaccines Differs from an Infection

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

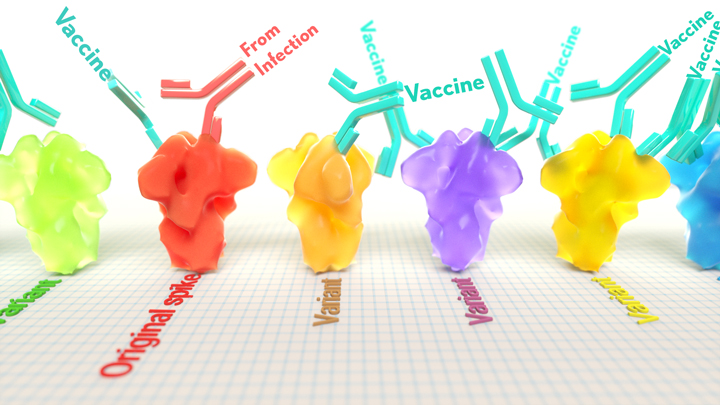

A key issue as we move closer to ending the pandemic is determining more precisely how long people exposed to SARS-CoV-2, the COVID-19 virus, will make neutralizing antibodies against this dangerous coronavirus. Finding the answer is also potentially complicated with new SARS-CoV-2 “variants of concern” appearing around the world that could find ways to evade acquired immunity, increasing the chances of new outbreaks.

Now, a new NIH-supported study shows that the answer to this question will vary based on how an individual’s antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 were generated: over the course of a naturally acquired infection or from a COVID-19 vaccine. The new evidence shows that protective antibodies generated in response to an mRNA vaccine will target a broader range of SARS-CoV-2 variants carrying “single letter” changes in a key portion of their spike protein compared to antibodies acquired from an infection.

These results add to evidence that people with acquired immunity may have differing levels of protection to emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants. More importantly, the data provide further documentation that those who’ve had and recovered from a COVID-19 infection still stand to benefit from getting vaccinated.

These latest findings come from Jesse Bloom, Allison Greaney, and their team at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle. In an earlier study, this same team focused on the receptor binding domain (RBD), a key region of the spike protein that studs SARS-CoV-2’s outer surface. This RBD is especially important because the virus uses this part of its spike protein to anchor to another protein called ACE2 on human cells before infecting them. That makes RBD a prime target for both naturally acquired antibodies and those generated by vaccines. Using a method called deep mutational scanning, the Seattle group’s previous study mapped out all possible mutations in the RBD that would change the ability of the virus to bind ACE2 and/or for RBD-directed antibodies to strike their targets.

In their new study, published in the journal Science Translational Medicine, Bloom, Greaney, and colleagues looked again to the thousands of possible RBD variants to understand how antibodies might be expected to hit their targets there [1]. This time, they wanted to explore any differences between RBD-directed antibodies based on how they were acquired.

Again, they turned to deep mutational scanning. First, they created libraries of all 3,800 possible RBD single amino acid mutants and exposed the libraries to samples taken from vaccinated individuals and unvaccinated individuals who’d been previously infected. All vaccinated individuals had received two doses of the Moderna mRNA vaccine. This vaccine works by prompting a person’s cells to produce the spike protein, thereby launching an immune response and the production of antibodies.

By closely examining the results, the researchers uncovered important differences between acquired immunity in people who’d been vaccinated and unvaccinated people who’d been previously infected with SARS-CoV-2. Specifically, antibodies elicited by the mRNA vaccine were more focused to the RBD compared to antibodies elicited by an infection, which more often targeted other portions of the spike protein. Importantly, the vaccine-elicited antibodies targeted a broader range of places on the RBD than those elicited by natural infection.

These findings suggest that natural immunity and vaccine-generated immunity to SARS-CoV-2 will differ in how they recognize new viral variants. What’s more, antibodies acquired with the help of a vaccine may be more likely to target new SARS-CoV-2 variants potently, even when the variants carry new mutations in the RBD.

It’s not entirely clear why these differences in vaccine- and infection-elicited antibody responses exist. In both cases, RBD-directed antibodies are acquired from the immune system’s recognition and response to viral spike proteins. The Seattle team suggests these differences may arise because the vaccine presents the viral protein in slightly different conformations.

Also, it’s possible that mRNA delivery may change the way antigens are presented to the immune system, leading to differences in the antibodies that get produced. A third difference is that natural infection only exposes the body to the virus in the respiratory tract (unless the illness is very severe), while the vaccine is delivered to muscle, where the immune system may have an even better chance of seeing it and responding vigorously.

Whatever the underlying reasons turn out to be, it’s important to consider that humans are routinely infected and re-infected with other common coronaviruses, which are responsible for the common cold. It’s not at all unusual to catch a cold from seasonal coronaviruses year after year. That’s at least in part because those viruses tend to evolve to escape acquired immunity, much as SARS-CoV-2 is now in the process of doing.

The good news so far is that, unlike the situation for the common cold, we have now developed multiple COVID-19 vaccines. The evidence continues to suggest that acquired immunity from vaccines still offers substantial protection against the new variants now circulating around the globe.

The hope is that acquired immunity from the vaccines will indeed produce long-lasting protection against SARS-CoV-2 and bring an end to the pandemic. These new findings point encouragingly in that direction. They also serve as an important reminder to roll up your sleeve for the vaccine if you haven’t already done so, whether or not you’ve had COVID-19. Our best hope of winning this contest with the virus is to get as many people immunized now as possible. That will save lives, and reduce the likelihood of even more variants appearing that might evade protection from the current vaccines.

Reference:

[1] Antibodies elicited by mRNA-1273 vaccination bind more broadly to the receptor binding domain than do those from SARS-CoV-2 infection. Greaney AJ, Loes AN, Gentles LE, Crawford KHD, Starr TN, Malone KD, Chu HY, Bloom JD. Sci Transl Med. 2021 Jun 8.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Bloom Lab (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle)

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

How COVID-19 Can Lead to Diabetes

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Along with the pneumonia, blood clots, and other serious health concerns caused by SARS-CoV-2, the COVID-19 virus, some studies have also identified another troubling connection. Some people can develop diabetes after an acute COVID-19 infection.

What’s going on? Two new NIH-supported studies, now available as pre-proofs in the journal Cell Metabolism [1,2], help to answer this important question, confirming that SARS-CoV-2 can target and impair the body’s insulin-producing cells.

Type 1 diabetes occurs when beta cells in the pancreas don’t secrete enough insulin to allow the body to metabolize food optimally after a meal. As a result of this insulin insufficiency, blood glucose levels go up, the hallmark of diabetes.

Earlier lab studies had suggested that SARS-CoV-2 can infect human beta cells [3]. They also showed that this dangerous virus can replicate in these insulin-producing beta cells, to make more copies of itself and spread to other cells [4].

The latest work builds on these earlier studies to discover more about the connection between COVID-19 and diabetes. The work involved two independent NIH-funded teams, one led by Peter Jackson, Stanford University School of Medicine, Palo Alto, CA, and the other by Shuibing Chen, Weill Cornell Medicine, New York. I’m actually among the co-authors on the study by the Chen team, as some of the studies were conducted in my lab at NIH’s National Human Genome Research Institute, Bethesda, MD.

Both studies confirmed infection of pancreatic beta cells in autopsy samples from people who died of COVID-19. Additional studies by the Jackson team suggest that the coronavirus may preferentially infect the insulin-producing beta cells.

This also makes biological sense. Beta cells and other cell types in the pancreas express the ACE2 receptor protein, the TMPRSS2 enzyme protein, and neuropilin 1 (NRP1), all of which SARS-CoV-2 depends upon to enter and infect human cells. Indeed, the Chen team saw signs of the coronavirus in both insulin-producing beta cells and several other pancreatic cell types in the studies of autopsied pancreatic tissue.

The new findings also show that the coronavirus infection changes the function of islets—the pancreatic tissue that contains beta cells. Both teams report evidence that infection with SARS-CoV-2 leads to reduced production and release of insulin from pancreatic islet tissue. The Jackson team also found that the infection leads directly to the death of some of those all-important beta cells. Encouragingly, they showed this could avoided by blocking NRP1.

In addition to the loss of beta cells, the infection also appears to change the fate of the surviving cells. Chen’s team performed single-cell analysis to get a careful look at changes in the gene activity within pancreatic cells following SARS-CoV-2 infection. These studies showed that beta cells go through a process of transdifferentiation, in which they appeared to get reprogrammed.

In this process, the cells begin producing less insulin and more glucagon, a hormone that encourages glycogen in the liver to be broken down into glucose. They also began producing higher levels of a digestive enzyme called trypsin 1. Importantly, they also showed that this transdifferentiation process could be reversed by a chemical (called trans-ISRIB) known to reduce an important cellular response to stress.

The consequences of this transdifferentiation of beta cells aren’t yet clear, but would be predicted to worsen insulin deficiency and raise blood glucose levels. More study is needed to understand how SARS-CoV-2 reaches the pancreas and what role the immune system might play in the resulting damage. Above all, this work provides yet another reminder of the importance of protecting yourself, your family members, and your community from COVID-19 by getting vaccinated if you haven’t already—and encouraging your loved ones to do the same.

References:

[1] SARS-CoV-2 infection induces beta cell transdifferentiation. Tang et al. Cell Metab 2021 May 19;S1550-4131(21)00232-1.

[2] SARS-CoV-2 infects human pancreatic beta cells and elicits beta cell impairment. Wu et al. Cell Metab. 2021 May 18;S1550-4131(21)00230-8.

[3] A human pluripotent stem cell-based platform to study SARS-CoV-2 tropism and model virus infection in human cells and organoids. Yang L, Han Y, Nilsson-Payant BE, Evans T, Schwartz RE, Chen S, et al. Cell Stem Cell. 2020 Jul 2;27(1):125-136.e7.

[4] SARS-CoV-2 infects and replicates in cells of the human endocrine and exocrine pancreas. Müller JA, Groß R, Conzelmann C, Münch J, Heller S, Kleger A, et al. Nat Metab. 2021 Feb;3(2):149-165.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Type 1 Diabetes (National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Disorders/NIH)

Jackson Lab (Stanford Medicine, Palo Alto, CA)

Shuibing Chen Laboratory (Weill Cornell Medicine, New York City)

NIH Support: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; National Human Genome Research Institute; National Institute of General Medical Sciences; National Cancer Institute; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development

U.K. Study Shows Power of Digital Contact Tracing for COVID-19

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

There’s been much interest in using digital technology to help contain the spread of COVID-19 in our communities. The idea is to make available opt-in smart phone apps that create a log of other apps operating on the phones of nearby participants. If a participant tests positive for COVID-19 and enters the result, the app will then send automatic alerts to those phones—and participants—who recently came into close proximity with them.

In theory, digital tracing would be much faster and more efficient than the challenging detective work involved in traditional contract tracing. But many have wondered how well such an opt-in system would work in practice. A recent paper, published in the journal Nature, shows that a COVID-19 digital tracing app worked quite well in the United Kingdom [1].

The research comes from Christophe Fraser, Oxford University, and his colleagues in the U.K. The team studied the NHS COVID-19 app, the National Health Service’s digital tracing smart phone app for England and Wales. Launched in September 2020, the app has been downloaded onto 21 million devices and used regularly by about half of eligible smart phone users, ages 16 and older. That’s 16.5 million of 33.7 million people, or more than a quarter of the total population of England and Wales.

From the end of September through December 2020, the app sent about 1.7 million exposure notifications. That’s 4.4 on average for every person with COVID-19 who opted-in to the digital tracing app.

The researchers estimate that around 6 percent of app users who received notifications of close contact with a positive case went on to test positive themselves. That’s similar to what’s been observed in traditional contact tracing.

Next, they used two different approaches to construct mathematical and statistical models to determine how likely it was that a notified contact, if infected, would quarantine in a timely manner. Though the two approaches arrived at somewhat different answers, their combined outputs suggest that the app may have stopped anywhere from 200,000 to 900,000 infections in just three months. This means that roughly one case was averted for each COVID-19 case that consented to having their contacts notified through the app.

Of course, these apps are only as good as the total number of people who download and use them faithfully. They estimate that for every 1 percent increase in app users, the number of COVID-19 cases could be reduced by another 1 or 2 percent. While those numbers might sound small, they can be quite significant when one considers the devastating impact that COVID-19 continues to have on the lives and livelihoods of people all around the world.

Reference:

[1] The epidemiological impact of the NHS COVID-19 App. Wymant C, Ferretti L, Tsallis D, Charalambides M, Abeler-Dörner L, Bonsall D, Hinch R, Kendall M, Milsom L, Ayres M, Holmes C, Briers M, Fraser C. Nature. 2021 May 12.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Christophe Fraser (Oxford University, UK)

Human Antibodies Target Many Parts of Coronavirus Spike Protein

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

For many people who’ve had COVID-19, the infections were thankfully mild and relatively brief. But these individuals’ immune systems still hold onto enduring clues about how best to neutralize SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19. Discovering these clues could point the way for researchers to design highly targeted treatments that could help to save the lives of folks with more severe infections.

An NIH-funded study, published recently in the journal Science, offers the most-detailed picture yet of the array of antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 found in people who’ve fully recovered from mild cases of COVID-19. This picture suggests that an effective neutralizing immune response targets a wider swath of the virus’ now-infamous spike protein than previously recognized.

To date, most studies of natural antibodies that block SARS-CoV-2 have zeroed in on those that target a specific portion of the spike protein known as the receptor-binding domain (RBD)—and with good reason. The RBD is the portion of the spike that attaches directly to human cells. As a result, antibodies specifically targeting the RBD were an excellent place to begin the search for antibodies capable of fending off SARS-CoV-2.

The new study, led by Gregory Ippolito and Jason Lavinder, The University of Texas at Austin, took a different approach. Rather than narrowing the search, Ippolito, Lavinder, and colleagues analyzed the complete repertoire of antibodies against the spike protein from four people soon after their recoveries from mild COVID-19.

What the researchers found was a bit of a surprise: the vast majority of antibodies—about 84 percent—targeted other portions of the spike protein than the RBD. This suggests a successful immune response doesn’t concentrate on the RBD. It involves production of antibodies capable of covering areas across the entire spike.

The researchers liken the spike protein to an umbrella, with the RBD at the tip of the “canopy.” While some antibodies do bind RBD at the tip, many others apparently target the protein’s canopy, known as the N-terminal domain (NTD).

Further study in cell culture showed that NTD-directed antibodies do indeed neutralize the virus. They also prevented a lethal mouse-adapted version of the coronavirus from infecting mice.

One reason these findings are particularly noteworthy is that the NTD is one part of the viral spike protein that has mutated frequently, especially in several emerging variants of concern, including the B.1.1.7 “U.K. variant” and the B.1.351 “South African variant.” It suggests that one reason these variants are so effective at evading our immune systems to cause breakthrough infections, or re-infections, is that they’ve mutated their way around some of the human antibodies that had been most successful in combating the original coronavirus variant.

Also noteworthy, about 40 percent of the circulating antibodies target yet another portion of the spike called the S2 subunit. This finding is especially encouraging because this portion of SARS-CoV-2 does not seem as mutable as the NTD segment, suggesting that S2-directed antibodies might offer a layer of protection against a wider array of variants. What’s more, the S2 subunit may make an ideal target for a possible pan-coronavirus vaccine since this portion of the spike is widely conserved in SARS-CoV-2 and related coronaviruses.

Taken together, these findings will prove useful for designing COVID-19 vaccine booster shots or future vaccines tailored to combat SARS-COV-2 variants of concern. The findings also drive home the conclusion that the more we learn about SARS-CoV-2 and the immune system’s response to neutralize it, the better position we all will be in to thwart this novel coronavirus and any others that might emerge in the future.

Reference:

[1] Prevalent, protective, and convergent IgG recognition of SARS-CoV-2 non-RBD spike epitopes. Voss WN, Hou YJ, Johnson NV, Delidakis G, Kim JE, Javanmardi K, Horton AP, Bartzoka F, Paresi CJ, Tanno Y, Chou CW, Abbasi SA, Pickens W, George K, Boutz DR, Towers DM, McDaniel JR, Billick D, Goike J, Rowe L, Batra D, Pohl J, Lee J, Gangappa S, Sambhara S, Gadush M, Wang N, Person MD, Iverson BL, Gollihar JD, Dye J, Herbert A, Finkelstein IJ, Baric RS, McLellan JS, Georgiou G, Lavinder JJ, Ippolito GC. Science. 2021 May 4:eabg5268.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Gregory Ippolito (University of Texas at Austin)

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; National Cancer Institute; National Institute of General Medical Sciences; National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences

How Severe COVID-19 Can Tragically Lead to Lung Failure and Death

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

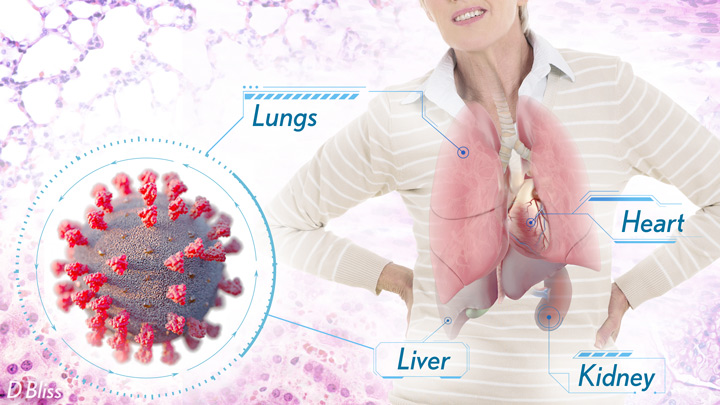

More than 3 million people around the world, now tragically including thousands every day in India, have lost their lives to severe COVID-19. Though incredible progress has been made in a little more than a year to develop effective vaccines, diagnostic tests, and treatments, there’s still much we don’t know about what precisely happens in the lungs and other parts of the body that leads to lethal outcomes.

Two recent studies in the journal Nature provide some of the most-detailed analyses yet about the effects on the human body of SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19 [1,2]. The research shows that in people with advanced infections, SARS-CoV-2 often unleashes a devastating series of host events in the lungs prior to death. These events include runaway inflammation and rampant tissue destruction that the lungs cannot repair.

Both studies were supported by NIH. One comes from a team led by Benjamin Izar, Columbia University, New York. The other involves a group led by Aviv Regev, now at Genentech, and formerly at Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, MA.

Each team analyzed samples of essential tissues gathered from COVID-19 patients shortly after their deaths. Izar’s team set up a rapid autopsy program to collect and freeze samples within hours of death. He and his team performed single-cell RNA sequencing on about 116,000 cells from the lung tissue of 19 men and women. Similarly, Regev’s team developed an autopsy biobank that included 420 total samples from 11 organ systems, which were used to generate multiple single-cell atlases of tissues from the lung, kidney, liver, and heart.

Izar’s team found that the lungs of people who died of COVID-19 were filled with immune cells called macrophages. While macrophages normally help to fight an infectious virus, they seemed in this case to produce a vicious cycle of severe inflammation that further damaged lung tissue. The researchers also discovered that the macrophages produced high levels of IL-1β, a type of small inflammatory protein called a cytokine. This suggests that drugs to reduce effects of IL-1β might have promise to control lung inflammation in the sickest patients.

As a person clears and recovers from a typical respiratory infection, such as the flu, the lung repairs the damage. But in severe COVID-19, both studies suggest this isn’t always possible. Not only does SARS-CoV-2 destroy cells within air sacs, called alveoli, that are essential for the exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide, but the unchecked inflammation apparently also impairs remaining cells from repairing the damage. In fact, the lungs’ regenerative cells are suspended in a kind of reparative limbo, unable to complete the last steps needed to replace healthy alveolar tissue.

In both studies, the lung tissue also contained an unusually large number of fibroblast cells. Izar’s team went a step further to show increased numbers of a specific type of pathological fibroblast, which likely drives the rapid lung scarring (pulmonary fibrosis) seen in severe COVID-19. The findings point to specific fibroblast proteins that may serve as drug targets to block deleterious effects.

Regev’s team also describes how the virus affects other parts of the body. One surprising discovery was there was scant evidence of direct SARS-CoV-2 infection in the liver, kidney, or heart tissue of the deceased. Yet, a closer look heart tissue revealed widespread damage, documenting that many different coronary cell types had altered their genetic programs. It’s still to be determined if that’s because the virus had already been cleared from the heart prior to death. Alternatively, the heart damage might not be caused directly by SARS-CoV-2, and may arise from secondary immune and/or metabolic disruptions.

Together, these two studies provide clearer pictures of the pathology in the most severe and lethal cases of COVID-19. The data from these cell atlases has been made freely available for other researchers around the world to explore and analyze. The hope is that these vast data sets, together with future analyses and studies of people who’ve tragically lost their lives to this pandemic, will improve our understanding of long-term complications in patients who’ve survived. They also will now serve as an important foundational resource for the development of promising therapies, with the goal of preventing future complications and deaths due to COVID-19.

References:

[1] A molecular single-cell lung atlas of lethal COVID-19. Melms JC, Biermann J, Huang H, Wang Y, Nair A, Tagore S, Katsyv I, Rendeiro AF, Amin AD, Schapiro D, Frangieh CJ, Luoma AM, Filliol A, Fang Y, Ravichandran H, Clausi MG, Alba GA, Rogava M, Chen SW, Ho P, Montoro DT, Kornberg AE, Han AS, Bakhoum MF, Anandasabapathy N, Suárez-Fariñas M, Bakhoum SF, Bram Y, Borczuk A, Guo XV, Lefkowitch JH, Marboe C, Lagana SM, Del Portillo A, Zorn E, Markowitz GS, Schwabe RF, Schwartz RE, Elemento O, Saqi A, Hibshoosh H, Que J, Izar B. Nature. 2021 Apr 29.

[2] COVID-19 tissue atlases reveal SARS-CoV-2 pathology and cellular targets. Delorey TM, Ziegler CGK, Heimberg G, Normand R, Shalek AK, Villani AC, Rozenblatt-Rosen O, Regev A. et al. Nature. 2021 Apr 29.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Izar Lab (Columbia University, New York)

Aviv Regev (Genentech, South San Francisco, CA)

NIH Support: National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Cancer Institute; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; National Human Genome Research Institute; National Institute of Mental Health; National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism

Dynamic View of Spike Protein Reveals Prime Targets for COVID-19 Treatments

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

This striking portrait features the spike protein that crowns SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19. This highly flexible protein has settled here into one of its many possible conformations during the process of docking onto a human cell before infecting it.

This portrait, however, isn’t painted on canvas. It was created on a computer screen from sophisticated 3D simulations of the spike protein in action. The aim was to map its many shape-shifting maneuvers accurately at the atomic level in hopes of detecting exploitable structural vulnerabilities to thwart the virus.

For example, notice the many chain-like structures (green) that adorn the protein’s surface (white). They are sugar molecules called glycans that are thought to shield the spike protein by sweeping away antibodies. Also notice areas (purple) that the simulation identified as the most-attractive targets for antibodies, based on their apparent lack of protection by those glycans.

This work, published recently in the journal PLoS Computational Biology [1], was performed by a German research team that included Mateusz Sikora, Max Planck Institute of Biophysics, Frankfurt. The researchers used a computer application called molecular dynamics (MD) simulation to power up and model the conformational changes in the spike protein on a time scale of a few microseconds. (A microsecond is 0.000001 second.)

The new simulations suggest that glycans act as a dynamic shield on the spike protein. They liken them to windshield wipers on a car. Rather than being fixed in space, those glycans sweep back and forth to protect more of the protein surface than initially meets the eye.

But just as wipers miss spots on a windshield that lie beyond their tips, glycans also miss spots of the protein just beyond their reach. It’s those spots that the researchers suggest might be prime targets on the spike protein that are especially promising for the design of future vaccines and therapeutic antibodies.

This same approach can now be applied to identifying weak spots in the coronavirus’s armor. It also may help researchers understand more fully the implications of newly emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants. The hope is that by capturing this devastating virus and its most critical proteins in action, we can continue to develop and improve upon vaccines and therapeutics.

Reference:

[1] Computational epitope map of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Sikora M, von Bülow S, Blanc FEC, Gecht M, Covino R, Hummer G. PLoS Comput Biol. 2021 Apr 1;17(4):e1008790.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Mateusz Sikora (Max Planck Institute of Biophysics, Frankfurt, Germany)

The surprising properties of the coronavirus envelope (Interview with Mateusz Sikora), Scilog, November 16, 2020.

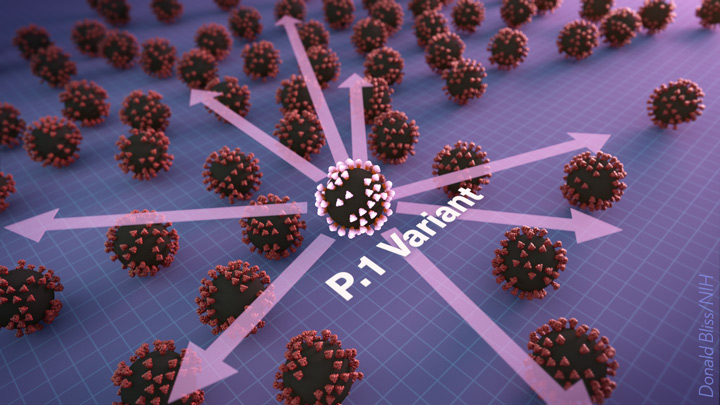

A Real-World Look at COVID-19 Vaccines Versus New Variants

Posted on by Dr. Francis Collins

Clinical trials have shown the COVID-19 vaccines now being administered around the country are highly effective in protecting fully vaccinated individuals from the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. But will they continue to offer sufficient protection as the frequency of more transmissible and, in some cases, deadly emerging variants rise?

More study and time is needed to fully answer this question. But new data from Israel offers an early look at how the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine is holding up in the real world against coronavirus “variants of concern,” including the B.1.1.7 “U.K. variant” and the B.1.351 “South African variant.” And, while there is some evidence of breakthrough infections, the findings overall are encouraging.

Israel was an obvious place to look for answers to breakthrough infections. By last March, more than 80 percent of the country’s vaccine-eligible population had received at least one dose of the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine. An earlier study in Israel showed that the vaccine offered 94 percent to 96 percent protection against infection across age groups, comparable to the results of clinical trials. But it didn’t dig into any important differences in infection rates with newly emerging variants, post-vaccination.

To dig a little deeper into this possibility, a team led by Adi Stern, Tel Aviv University, and Shay Ben-Shachar, Clalit Research Institute, Tel Aviv, looked for evidence of breakthrough infections in several hundred people who’d had at least one dose of the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine [1]. The idea was, if this vaccine were less effective in protecting against new variants of concern, the proportion of infections caused by them should be higher in vaccinated compared to unvaccinated individuals.

During the study, reported as a pre-print in MedRxiv, it became clear that B.1.1.7 was the predominant SARS-CoV-2 variant in Israel, with its frequency increasing over time. By comparison, the B.1.351 “South African” variant was rare, accounting for less than 1 percent of cases sampled in the study. No other variants of concern, as defined by the World Health Organization, were detected.

In total, the researchers sequenced SARS-CoV-2 from more than 800 samples, including vaccinated individuals and matched unvaccinated individuals with similar characteristics including age, sex, and geographic location. They identified nearly 250 instances in which an individual became infected with SARS-CoV-2 after receiving their first vaccine dose, meaning that they were only partially protected. Almost 150 got infected sometime after receiving the second dose.

Interestingly, the evidence showed that these breakthrough infections with the B.1.1.7 variant occurred slightly more often in people after the first vaccine dose compared to unvaccinated people. No evidence was found for increased breakthrough rates of B.1.1.7 a week or more after the second dose. In contrast, after the second vaccine dose, infection with the B.1.351 became slightly more frequent. The findings show that people remain susceptible to B.1.1.7 following a single dose of vaccine. They also suggest that the two-dose vaccine may be slightly less effective against B.1.351 compared to the original or B.1.1.7 variants.

It’s important to note, however, that the researchers only observed 11 infections with the B.1.351 variant—eight of them in individuals vaccinated with two doses. Interestingly, all eight tested positive seven to 13 days after receiving their second dose. No one in the study tested positive for this variant two weeks or more after the second dose.

Many questions remain, including whether the vaccines reduced the duration and/or severity of infections. Nevertheless, the findings are a reminder that—while these vaccines offer remarkable protection—they are not foolproof. Breakthrough infections can and do occur.

In fact, in a recent report in the New England Journal of Medicine, NIH-supported researchers detailed the experiences of two fully vaccinated individuals in New York who tested positive for COVID-19 [2]. Though both recovered quickly at home, genomic data in those cases revealed multiple mutations in both viral samples, including a variant first identified in South Africa and Brazil, and another, which has been spreading in New York since November.

These findings in Israel and the United States also highlight the importance of tracking coronavirus variants and making sure that all eligible individuals get fully vaccinated as soon as they have the opportunity. They show that COVID-19 testing will continue to play an important role, even in those who’ve already been vaccinated. This is even more important now as new variants continue to rise in frequency.

Just over 100 million Americans aged 18 and older—about 40 percent of adults—are now fully vaccinated [3]. However, we need to get that number much higher. If you or a loved one haven’t yet been vaccinated, please consider doing so. It will help to save lives and bring this pandemic to an end.

References:

[1] Evidence for increased breakthrough rates of SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern in BNT162b2 mRNA vaccinated individuals. Kustin T et al. medRxiv. April 16, 2021.

[2] Vaccine breakthrough infections with SARS-CoV-2 variants. Hacisuleyman E, Hale C, Saito Y, Blachere NE, Bergh M, Conlon EG, Schaefer-Babajew DJ, DaSilva J, Muecksch F, Gaebler C, Lifton R, Nussenzweig MC, Hatziioannou T, Bieniasz PD, Darnell RB. N Engl J Med. 2021 Apr 21.

[3] COVID-19 vaccinations in the United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Stern Lab (Tel Aviv University, Israel)

Ben-Shachar Lab (Clalit Research Institute, Tel Aviv, Israel)

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

Previous Page Next Page